- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

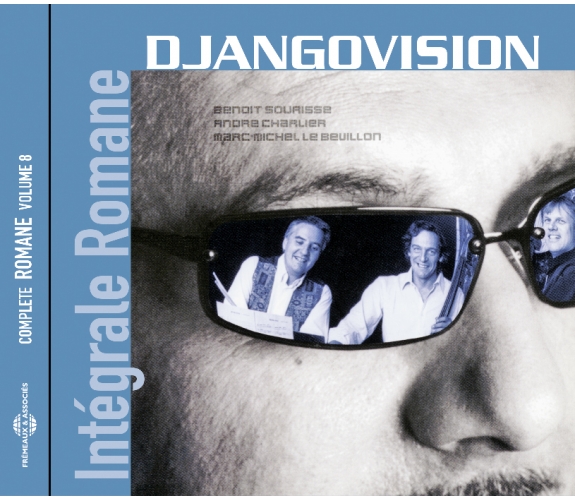

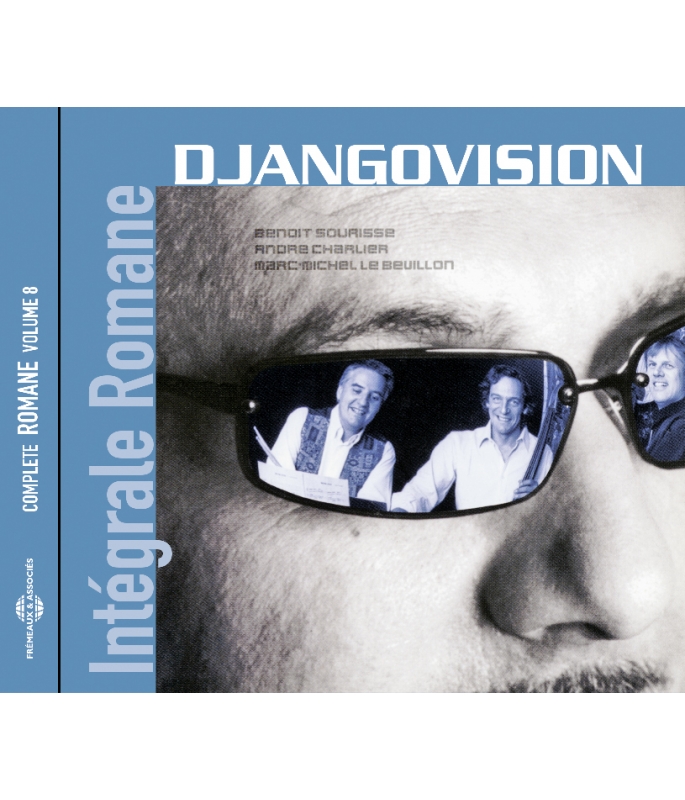

ROMANE

Ref.: FA546

Artistic Direction : Augustin Bondoux et Patrick Frémeaux

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 48 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

A tribute to Django Reinhardt can be an expected, relatively easy thing to do if you play jazz guitar, especially if your name is Romane, a spearhead on the gypsy-jazz scene.

Yet this «tribute album» from Romane deliberately goes against the grain in imagining the Master’s caravan coming to a halt outside the New York label Blue Note’s studios in the early 60’s.

As you might guess from its decidedly “Sixties” title, Romane peppers Django’s compositions with the then-nascent jazz-soul groove of musicians like Jimmy Smith, Brother Jack McDuff and Lonnie Smith.

Goodbye “pump”, goodbye traditional swing… Here Romane is in the company of an unavoidable duo—Benoît Sourisse (Hammond organ), André Charlier (drums)—and bassist Marc Michel Le Bévillon.

A success when first released, this album heralded “Roots & Groove” which surfaced nine years later (FA537), an album where Romane explored jazz-funk in an even more clear-cut vein.

Augustin BONDOUX

As the publisher of the complete recordings of Django Reinhardt — the set is a work of reference with 40CDs and booklets totalling 760 pages — Frémeaux & Associés today counts as one of the premier independent producers of gypsy jazz.

This genre, as erudite and technical as it is generous and approachable, demonstrates the cultural and musicological richness of the gypsy contribution to western culture. Romane is one of their most eminent representatives and his compositions have become genuine standards.

Frémeaux & Associés celebrates the work of this guitarist in a collection covering his entire career as a recording artist, available to the public as a “Complete Works” set with Djangovision as its eight volume.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

ROMANE (GUITARE) • BENOIT SOURISSE (ORGUE HAMMOND) • ANDRE CHARLIER (BATTERIE) • MARC-MICHEL LE BEVILLON (CONTREBASSE).

Romane joue sur une guitare Maurice Dupont modèle « Romane ».

PRODUCTION INITIALE : IRIS

DROITS / FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES EN ACCORD AVEC ROMANE.

LENTEMENT MADEMOISELLE (DJANGO REINHARDT) • RYTHME FUTUR / DJANGO TIGER (DJANGO REINHARDT) • ANOUMAN (DJANGO REINHARDT) • PÊCHE À LA MOUCHE (DJANGO REINHARDT) • PLACE DE BROUCKÈRE (DJANGO REINHARDT) • PORTO CABELLO (DJANGO REINHARDT) • BABIK (DJANGO REINHARDT) • MABEL (DJANGO REINHARDT) • STOCKHOLM (DJANGO REINHARDT).

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Lentement MademoiselleRomane, Benoit Sourisse, André Charlier, Marc-Michel Le Bevillon00:02:422003

-

2Rythme Futur/Django TigerRomane, Benoit Sourisse, André Charlier, Marc-Michel Le Bevillon00:06:242003

-

3AnoumanRomane, Benoit Sourisse, André Charlier, Marc-Michel Le Bevillon00:05:372003

-

4Pêche à la moucheRomane, Benoit Sourisse, André Charlier, Marc-Michel Le Bevillon00:04:592003

-

5Place de BrouckèreRomane, Benoit Sourisse, André Charlier, Marc-Michel Le Bevillon00:04:122003

-

6Porto CabelloRomane, Benoit Sourisse, André Charlier, Marc-Michel Le Bevillon00:05:282003

-

7BabikRomane, Benoit Sourisse, André Charlier, Marc-Michel Le Bevillon00:05:362003

-

8MabelRomane, Benoit Sourisse, André Charlier, Marc-Michel Le Bevillon00:04:182003

-

9StockholmRomane, Benoit Sourisse, André Charlier, Marc-Michel Le Bevillon00:09:322003

Djangovision FA546

Djangovision

Intégrale RomanE Vol.8

DJANGOVISION – ROMANE

Lentement Mademoiselle (Django Reinhardt) (02’42)

Rythme Futur / Django Tiger (Django Reinhardt) (06’24)

Anouman (Django Reinhardt) (05’37)

Pêche à la mouche (Django Reinhardt) (04’59)

Place de Brouckère (Django Reinhardt) (04’12)

Porto Cabello (Django Reinhardt) (05’28)

Babik (Django Reinhardt) (05’36)

Mabel (Django Reinhardt) (04’18)

Stockholm (Django Reinhardt) (09’32)

Durée Totale 48’53

ROMANE : Guitare

BENOIT SOURISSE : Orgue Hammond

ANDRE CHARLIER : Batterie

MARC-MICHEL LE BEVILLON : Contrebasse

Romane joue sur une guitare Maurice Dupont modèle « Romane »

Enregistré et mixé au studio Big Bone (Monthomé) du 16 au 22 décembre 2002 et du 5 au 7 février 2003

Prise de son et mixage : Alexis Blanchart

Mastering : DYAM

Photo couverture : Gilbert Gibdouny

Conception graphique : Christophe Rémy

Droits Master : Groupe Frémeaux Colombini SAS

Direction réédition Intégrale Romane :

Patrick Frémeaux avec Benjamin Goldenstein et Augustin Bondoux

Première parution en 2003 chez Iris music production

Frémeaux & Associés cessionnaire 2010-2016

« Notre héritage n’est précédé d’aucun testament » écrivait René Char…

Cet aphorisme réconfortant, que le poète a sans nul doute voulu aussi prometteur que stimulant n’aurait certes pas déplu à notre ami Django, lui qui tout au long de sa courte et prolifique carrière, curieux de tout et sensible aux révolutions, prit un soin méticuleux à constamment se renouveler et faire évoluer sa musique. Et Romane, qui connaît pourtant sa djangologie par cœur et sur le bout des doigts semble, dès le début, l’avoir parfaitement compris.

Car, à l’heure où la parole de Django est révérée comme une sainte écriture et son répertoire consacré comme une Nouvelle Alliance par de zélés et souvent trop appliqués disciples, qu’il est bon de redécouvrir une perle iconoclaste comme « Djangovision » !

Lors de la sortie initiale de l’album, en 2003, le revival manouche battait déjà son plein. Les compilations estampillées « Gipsy Jazz » qui envahissent aujourd’hui nos bacs apparaissaient pour la première fois. De nouveaux artistes surgissaient de nulle part et d’autres, qu’on avait un peu oubliés, étaient subitement redécouverts. La radio passait Sanseverino et même le cinéma américain se prenait soudainement de passion pour cette musique « so warm, and so romantic ». L’heure était à Django... et à son essaim de clones.

Je me souviens alors très bien que dans cette ambiance frénétique et jubilatoire, la sortie de « Djangovision » fût parfois un peu houleuse. Oh, les reproches de certains fanatiques étaient attendus, on connaît la chanson : « il n’y a pas de pompe », « ça ne sent pas le feu de bois », « trop électrique », « pas assez de guitare », « drôle de son », « trop moderne »… Triste réquisitoire qui pouvait donc se tenir en deux mots : trop moderne, la musique à Django !

Car il faut dire que pour beaucoup d’amateurs de jazz manouche, comme il est convenu aujourd’hui d’appeler la musique inventée par Django Reinhardt, le style se limite à ce que le Quintette du Hot Club de France produisit entre 1934 et 1939 ; c’est à dire entre l’inauguration du quintet historique et le départ de Stéphane Grappelli qui préférera l’exil londonien à une occupation germanique. Période faste et comblée de chefs-d’œuvre, on ne le dira jamais assez, qui culminera avec l’incontournable « Minor Swing » de 1937 : quel guitariste n’a pas usé ses doigts sur ce solo légendaire de Django ? Quel enthousiaste n’a jamais chantonné cet hymne à ce jazz tellement français… ? Mais se limiter à cette période sans tambour ni trompette, c’est hélas se priver des chefs d’œuvres à venir.

Et c’est aussi oublier que Django, éternel amoureux de la musique et qui resta toute sa vie à l’écoute attentive de ses contemporains, n’était pas seulement un phénoménal instrumentiste, un exceptionnel improvisateur, mais également un compositeur de génie. Avait-il alors ce don de prescience que semble lui accorder Romane dans ses « Djangovisions » ? Les gitans ont, paraît-il, le don surnaturel de pouvoir lire l’avenir dans les boules de cristal… Reconnaissons seulement que l’audace harmonique et la modernité rythmique de certaines de ses compositions, notamment celles de la dernière manière, apparaissent aujourd’hui très troublantes. Car enfin, est-il vraiment si insensé d’entendre Duke Ellington dans « Lentement Mademoiselle », Charlie Parker dans « Babik », Dizzy Gillespie dans « Rythme Futur », Thelonious Monk dans « Mabel » et surtout « Stockholm » une de ses compositions les plus ambitieuses, John Coltrane dans « Anouman » (« Naïma » nous tient la main…), Charlie Mingus dans « «Porto Cabello », et osons même, Ornette Coleman dans « Rythme Futur », encore une fois… ? Certes, après-coup, l’exercice est toujours facile. Mais si vous pensez comme moi, alors oui, Django était un visionnaire.

Romane est quant à lui l’un des plus fameux représentant du « jazz manouche » actuel. Tout au long de sa carrière, avec plus d’une quinzaine d’albums et d’illustres collaborations, un journal mythique (« French Guitare »), des publicités, quelques méthodes de guitare et même deux écoles, il n’a jamais ânonné, comme tant d’autres, la musique de Django. Dès les premiers disques (« Swing for Ninine », « Quintet », « Ombre »…) son répertoire privilégiait déjà l’aventure des compositions aux sempiternelles et stériles reprises de standards qui encombrent si souvent les disques et les compils actuels. Son style est parfaitement reconnaissable et sans rien renier du vocabulaire du Maître, il a suivi son propre chemin. Il n’est finalement pas très étonnant qu’un beau jour, ce grand admirateur de Django s’intéressa de près à son répertoire le plus secret et le plus audacieux. Celui des meilleurs amis.

Pour le soutenir, Romane a choisi une formule guitare/hammond/basse/batterie inédite chez Django mais qui a fait ses preuves dans le jazz : parlez-en à Wes Montgomery, à René Thomas et Kenny Burrell ou plus récemment, à David Reinhardt, fils de Babik, lui-même fils de qui vous savez. Marc-Michel Le Bévillon, l’ami de toujours, tient la contrebasse et ne se contente pas de lignes (écoutez bien son solo sur « Babik »), et le couple indissociable Benoît Sourisse (B-3) André Charlier (batterie) formidable d’invention, d’écoute et de soutient a depuis parcouru le chemin que l’on sait, disques à l’appui. C’est donc une rythmique de tout premier ordre qui accompagne le guitariste dans la redécouverte, et la ré-écriture, de ce répertoire d’exception.

Django n’a pas laissé de testament : il n’y a pas de devoir de mémoire, aucune promesse à tenir et son héritage, dirait Hannah Arendt « ne nous assigne pas un passé sans avenir ». Au contraire. Django nous laisse une œuvre qu’il nous appartient de faire vivre dans le mouvement, avec audace et avec imagination. Avec impertinence. Et « Djangovision », en y faisant éclater l’incroyable modernité d’un discours en perpétuelle évolution autant que par son interprétation discrètement irrespectueuse nous invite à relire ce répertoire avec plus de naturel, plus de caractère et plus de liberté. A le regarder d’un peu plus haut. La tête dans les nuages… ? Peut-être.

Ce qui est certain, en revanche, c’est qu’avec Romane, la musique de Django se réveille.

Sébastien LÉGÉ

Chroniqueur pour www.djangostation.com

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

“Our legacy has no last will and testament which precedes it,” wrote René Char…

It’s a comforting maxim, one that poet René Char no doubt intended to be as promising as it was stimulating, and Django would have liked it. Throughout his brief yet prolific career, the Gypsy Master was curious of everything, and sensitive to revolutions, taking meticulous care to constantly renew his music and cause it to evolve. And Romane, even though he knows his “Djangology” by heart (all the way to his fingertips), seems to have perfectly understood him from the beginning.

Proof, if needed, now that the word of Django is revered like Holy Scripture, and his repertoire is considered by zealots (and other, often over-industrious disciples) as some “New Alliance”, lies in the fact that any rediscovery of such an iconoclastic gem as Djangovision is an extremely good thing!

When this album was first released (2003), the “gypsy-jazz revival” was already booming. Compilations with the “Gypsy Jazz” banner (which today invade the record-bins) were appearing for the first time; new artists were springing up from nowhere, and others, whom we’d somewhat forgotten, were suddenly being rediscovered. French radio was playing Sanseverino, and even American films were suddenly developing a passion for this music which was, “So warm, and so romantic.” Django was “in”, and so were swarms of clones.

So I well remember that the release of Djangovision, in that ambiance of frenzy and jubilation, had a sometimes turbulent reception. Oh, the reproachful tone of some fanatics was expected, of course: you somehow knew they were going to say, “There’s no pump” or, “You can’t smell the wood-smoke.” They said, “too electric”, “not enough guitar”, “weird sound” and “too modern”… Sad indictments, and they could be resumed in a few words: Django’s music was too modern!

It has to be said that, for many fans of gypsy-jazz—the convenient name today given to the music invented by Django Reinhardt—, the style was limited to the music produced by the “Quintette du Hot Club de France” between 1934 and 1939; in other words, between the inauguration of that historic Quintet and the departure of Stéphane Grappelli, who preferred exile in London to Occupation by Germany. It was a rich period brimming with masterpieces—you can’t say that loud enough—and it reached its apogee with the inescapable title “Minor Swing” in 1937. Can you name one guitarist who hasn’t worn his fingers to the bone over that legendary solo by Django? Or any enthusiast who never hummed that hymn to such a particularly French form of jazz? The fact remains, however: if you confine yourself to that period with “no trumpet, no drums”, you will unfortunately also deprive yourself of masterpieces yet to come.

You’d also be forgetting that Django, a man with an undying love of music who throughout his life listened attentively to his contemporaries, was not only a phenomenal instrumentalist and exceptional improviser, but also a composer of genius. So did he have that gift of premonition which Romane seems to attribute to him in his own “Djangovisions”? Gypsies are said to have a supernatural gift: they can see the future in a crystal ball… Let us just recognize that the harmonic audacity and modern rhythm of some compositions, notably those he played in his later style, today seem quite troubling. Are we really so demented as to hear Duke Ellington in Lentement Mademoiselle, Charlie Parker in Babik, Dizzy Gillespie in Rythme Futur, Thelonious Monk in Mabel, and Stockholm especially (one of his most ambitious works), John Coltrane in Anouman (with Naïma taking us by the hand), Charlie Mingus in Porto Cabello and dare we say Ornette Coleman, in Rythme Futur again?... Of course, such an exercise always comes easily with hindsight. But if you think like I do, then yes, Django was a visionary.

Romane, for his part, is one of the most illustrious representatives of contemporary “gypsy jazz”. Throughout his career—with more than fifteen albums to his credit, illustrious collaborations, a legendary journal (“French Guitare”), adverts, a few guitar manuals, even two schools—Romane has never mumbled his way through Django’s music as so many others have done. By the time he made his first records—Swing for Ninine, Quintet, Ombre—his repertoire was already showing his preference for adventurous compositions, not the never-ending sterile “standard”-versions which so often clutter records and compilations today. His style is perfectly recognizable and, owing nothing to the vocabulary of the Master, Romane has followed his own course. In the end, it doesn’t come as that much of a surprise to see that one day this great admirer of Django took a close interest in the latter’s most secret, most daring compositions. Those preferred by his best friends.

To accomplish this, Romane chose a “guitar/Hammond/bass/drums” format which is unknown in Django’s work but which has proved its worth in jazz: just ask Wes Montgomery, René Thomas and Kenny Burrell or, more recently, David Reinhardt, son of Babik, himself the son of you-know-who. Marc-Michel Le Bévillon, always the friend, plays the double bass (and not merely the bass lines: listen closely to his solo on Babik), while the inseparable pair of Benoît Sourisse (B-3) and André Charlier (drums)—wonderfully inventive, supportive, close listeners—have continued a path which their recordings have made familiar to us all. So, a first-class rhythm-section appears here alongside the guitarist as he rediscovers (and rewrites) this exceptional repertoire.

Django left no “last will and testament”: there is no duty to perpetuate his memory, no promise to be kept, and his legacy, as Hannah Arendt would say, “assigns us no past without a future.” On the contrary, Django has left us a body of work which it is our responsibility to cause to live on in movement, and with boldness and emotion. With impertinence. And Djangovision, by exploding an incredible modernity into view—modern as much in its perpetually evolving discourse as in its discreetly irreverent performance—extends us an invitation to go back over this repertoire with even more naturalness, more character and more freedom. To look at it from a slightly higher perspective… with our head in the clouds? Perhaps.

What remains a certainty, on the other hand, is that with Romane, the music of Django comes awake.

Sébastien LÉGÉ

Columnist, www.djangostation.com

Adapted into English by Martin DAVIES

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

Rendre hommage à Django Reinhardt est une chose relativement aisée et attendue lorsque l’on est guitariste de jazz, et plus particulièrement pour Romane, l’un des fers de lance de la scène jazz-manouche. Toutefois pour son album « tribute », Romane prend résolument les choses à contre courant et s’imagine la verdine du Maitre s’arrêtant devant l’enseigne new-yorkaise du label Blue Note au début des années 1960. Comme son titre (qui sonne résolument sixties) l’indique, Romane assaisonne les compositions de Django Reinhardt au groove du jazz-soul émergeant au début des années 1960 de Jimmy Smith, Brother Jack McDuff ou Lonnie Smith. Adieu la pompe, adieu le swing traditionnel, Romane fait appel à l’incontournable duo Benoît Sourisse (orgue hammond) - André Charlier (batterie) et au contrebassiste Marc-Michel Le Bévillon. Un disque qui a rencontré un grand succès à sa sortie et qui annonce l’album « Roots & Groove » (FA537), qui paraitra 9 ans après, dans lequel le guitariste explorera un jazz-funk encore plus tranché et incisif. Augustin BONDOUX

Éditeur de l’intégrale discographique de Django Reinhardt de référence (40 CD, 760 pages de livrets), Frémeaux & Associés est aujourd’hui l’un des premiers producteurs indépendants de jazz manouche. Cette musique tant généreuse et accessible, que savante et technique, démontre la richesse culturelle et musicologique de l’apport du genre manouche à la culture occidentale. Romane en est l’un des plus éminents représentants et ses compositions sont devenues de véritables standards. Frémeaux & Associés célèbre l’oeuvre du guitariste en recueillant l’ensemble de sa carrière phonographique afin de la remettre à la disposition du public dans une Intégrale, dont Djangovision est le huitième volume. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Lentement Mademoiselle (Django Reinhardt) 2’42 • 2. Rythme Futur / Django Tiger (Django Reinhardt) 6’24 • 3. Anouman (Django Reinhardt) 5’37 • 4. Pêche à la mouche (Django Reinhardt) 4’59 • 5. Place de Brouckère (Django Reinhardt) 4’12 • 6. Porto Cabello (Django Reinhardt) 5’28 • 7. Babik (Django Reinhardt) 5’36 • 8. Mabel (Django Reinhardt) 4’18 • 9. Stockholm (Django Reinhardt) 9’32. Durée Totale 48’53

Romane : guitare • Benoit Sourisse : Orgue Hammond • Andre Charlier : Batterie • Marc-Michel Le Bevillon : Contrebasse.

Romane joue sur une guitare Maurice Dupont modèle « Romane ».

A tribute to Django Reinhardt can be an expected, relatively easy thing to do if you play jazz guitar, especially if your name is Romane, a spearhead on the gypsy-jazz scene. Yet this "tribute album" from Romane deliberately goes against the grain in imagining the Master’s caravan coming to a halt outside the New York label Blue Note’s studios in the early 60’s. As you might guess from its decidedly “Sixties” title, Romane peppers Django’s compositions with the then-nascent jazz-soul groove of musicians like Jimmy Smith, Brother Jack McDuff and Lonnie Smith. Goodbye “pump”, goodbye traditional swing… Here Romane is in the company of an unavoidable duo—Benoît Sourisse (Hammond organ), André Charlier (drums)—and bassist Marc-Michel Le Bévillon. A success when first released, this album heralded “Roots & Groove” which surfaced nine years later (FA537), an album where Romane explored jazz-funk in an even more clear-cut vein. Augustin BONDOUX

As the publisher of the complete recordings of Django Reinhardt — the set is a work of reference with 40CDs and booklets totalling 760 pages — Frémeaux & Associés today counts as one of the premier independent producers of gypsy jazz. This genre, as erudite and technical as it is generous and approachable, demonstrates the cultural and musicological richness of the gypsy contribution to western culture. Romane is one of their most eminent representatives and his compositions have become genuine standards. Frémeaux & Associés celebrates the work of this guitarist in a collection covering his entire career as a recording-artist, available to the public as a “Complete Works” set with Djangovision as its eight volume. Patrick FRÉMEAUX