- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

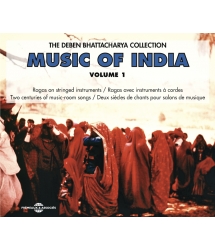

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

Ref.: FA060

EAN : 3448960206020

Artistic Direction : DEBEN BHATTACHARYA

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 42 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

- - ƒƒƒ TÉLÉRAMA

- - * * * LE MONDE DE LA MUSIQUE

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

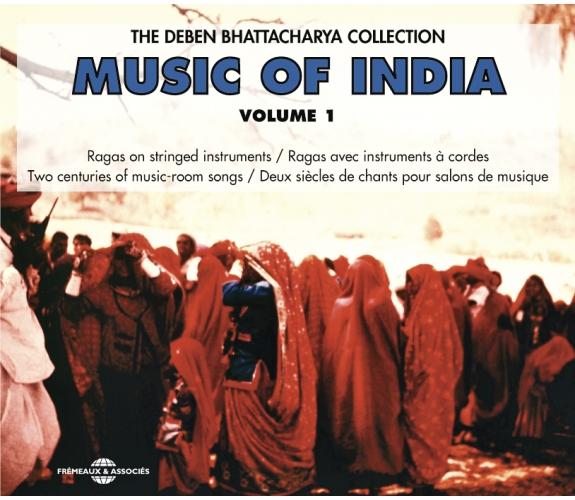

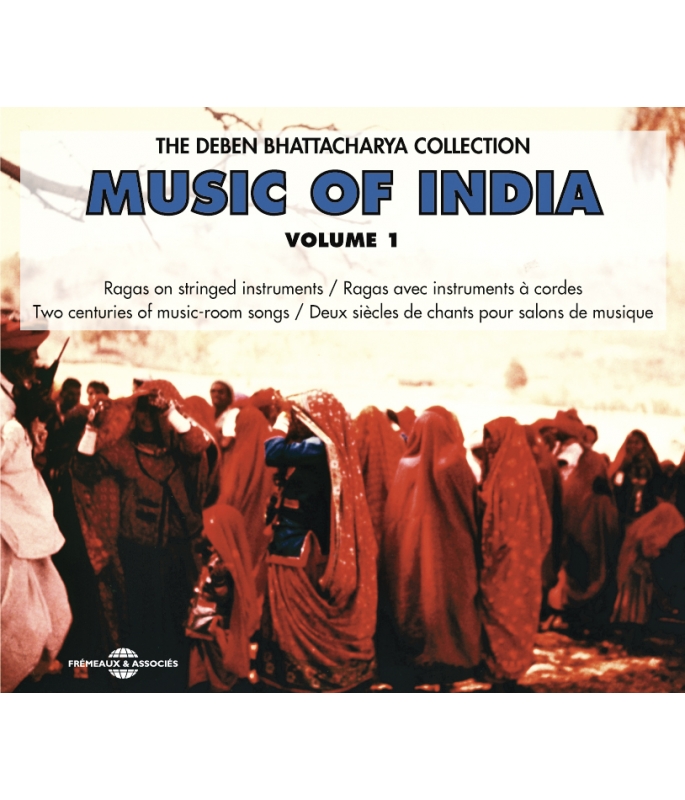

Ragas on string instruments - Two centuries of music-room songs coming straight from India. All songs featured in this 2-CD set come from the Deben Bhattacharya collection. Deben was an Indian born ethnomusicologist. He travelled the world and made some of the first live ethnic and folk recordings. This 2-CD set presents traditional music from India that Deben recorded himself. An unique testimony. Includes a 58 page booklet with both French and English notes.

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

BANDE ORIGINALE DU FILM DE STÉPHANE JOURDAIN

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1RAGA TODI ON SURBAHARTRADITIONNEL00:28:410

-

2RAGA MIYAN KI MALHAR ON RUDRAVINATRADITIONNEL00:07:120

-

3RAGA BIHAG ON RUDRAVINATRADITIONNEL00:07:140

-

4RAGA BHAIRAVI ON RUDRAVINATRADITIONNEL00:10:410

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1MON EKI BHRANTI TOMARTRADITIONNEL00:02:310

-

2KI SWADESHE KI BIDESHETRADITIONNEL00:02:120

-

3MALAY ASIYA KOYE GECHHE KANETRADITIONNEL00:03:180

-

4BHALOBESHE BHALO KANDALETRADITIONNEL00:02:470

-

5MON JE NILOTRADITIONNEL00:03:550

-

6AY MA SADHAN SAMARETRADITIONNEL00:04:030

-

7MAR DEOYA PRANETRADITIONNEL00:02:520

-

8SHUNYA E BUKETRADITIONNEL00:04:281996

-

9TOMAR ANDHAR NISHATRADITIONNEL00:03:201997

-

10MAHASINDHUR OPAR THEKETRADITIONNEL00:04:070

-

11SHYAM KANDANO BHALO NOYTRADITIONNEL00:06:070

-

12BUJHI OI SUDURETRADITIONNEL00:01:570

-

13SHAON ASHILO PHIRETRADITIONNEL00:07:300

THE DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION MUSIC OF INDIA

THE DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

MUSIC OF INDIA

Volume 1

Ragas on stringed instruments / Ragas avec instruments à cordes

Two centuries of music-room songs / Deux siècles de chants pour salons de musique

INTRODUCTION

Le domaine de prédilection Deben Bhattacharya est la collection, le tournage et l’enregistrement de la musique folklorique, la chanson, la danse ainsi que la musique classique en Asie et en Europe.Depuis 1955, il a réalisé des films éducatifs, des documentaires, des disques, des brochures, des émissions radiophoniques et des concerts en direct relatifs à ses recherches. Il a également édité des traductions de la poésie médiévale de l’Inde.Entre 1967 et 1974, il a produit des films éducatifs, des disques, des brochures et des concerts pour des écoles et des universités en Suède, sponsorisé par l’institut d’état de la musique éducative: Rikskonsorter.Ses travaux ont également consisté en documentaires pour la télévision ainsi que des émissions sur le folklore, les traditions... pour : • British Broadcasting Corporation, Londres • Svorigos Radio, Stockholm • Norsk Rikskringkasting, Oslo • B.R.T. - 3, Bruxelles • Filmes ARGO (Decca), Londres • Seabourne Enterprise Ltd., R.U. • D’autres stations de radio en Asie et en Europe.Deben Bhattacharya a réalisé plus de 130 disques de musique folklorique et classique, enregistrés dans près de trente pays en Asie et en Europe. Ces disques sont sortis sous les étiquettes suivantes : •Philips, Baarn, Hollande • ARGO (Decca), Londres • HMV & Columbia, Londres • Angel Records & Westminster Records, New York • OCORA, Disque BAM, Disque AZ, Contrepoint, Paris • Supraphone, Prague • HMV, Calcutta • Nippon Records, Tokyo.Deben Bhattacharya est également l’auteur de livres de traduction de la poésie médiévale indienne. Ces ouvrages ont été préparés pour la série de l’UNESCO, East-West Major Works, publiés simultanément en Angleterre et les Etats-Unis par G. Allen & Unwin, Londres, et par le Grove Press, New York, et par Hind Pocket Books, New Delhi. Les titres comprennent : • Love Songs of Vidyapati • Love Songs of Chandidas • The Mirror of the Sky: songs of the bards of Bengal • Songs of Krishna.Deben Bhattacharya fait paraître en 1997, une collection de coffrets thématiques chez Frémeaux & Associés, regroupant ses meilleurs enregistrements de Musique du Monde et dotés de livrets qui constituent un appareil critique de documentation incomparable.

Deben Bhattacharya is a specialist in collecting, filming and recording traditional music, song and dance in Asia, Europe and North Africa.Since 1955 he has been producing documentary films, records, illustrated books and radio programmes related to many aspects of his subject of research. His films for TV and programmes for radio on traditional music and rural life and customs have been broadcast by: • the BBC, Thames Television, Channel Four, London • WDR-Music TV, Cologne • Sveriges Radio/TV, Stockholm • BRT-3, Brussels • Doordarshan-TV, Calcutta • English TV, Singapore • and various other radio and television stations in Asia and Europe.Deben Bhattacharya has produced more than 130 albums of traditional music recorded in about thirty countries of Asia and Europe. These albums have been released by: • Philips, Baarn, Holland • ARGO (Decca Group), London • HMV & Clumbia, London • Angel Records & Westminster, New York • OCCORA, Disque BAM, Contrepoint, Paris • Supraphone, Prague • HMV, Calcutta • Nippon-Westminster & King Records, Tokyo.In addition, Deben Bhattacharya is the author of books of translations of Indian medieval poetry and songs. These publications have been prepared for the UNESCO’s East-West Major Works series published simultaneously in England and the USA by G. Allen & Unwin, London, and by the Grove Press, New York, and by Hind Pocket Books, New Delhi. The titles include: • Love Songs of Vidyapati • Love Songs of Chandidas • The Mirror of the Sky/Songs of the Bards of Bengal • Songs of Krishna.Deben Bhattacharya released a new collection of thematic double Cd Set, published by Frémeaux & Associés, with booklet comprising essentiel documentary and musicological information.

AVANT-PROPOS

En Inde, tout comme en Europe, on trouve une diversité de paysages et de climats, et y vivent aussi près d’un milliard d’habitants d’origines ethniques variées. L’Himalaya sépare le pays du reste de l’Asie, le transformant en quasi sous-continent. S’étendant sur 3 287 782 kilomètres carrés, l’Inde, en tant que République démocratique, comprend sept territoires à administration centralisée ainsi que vingt-cinq états auto-administrés. Chacun possède sa propre langue, littérature, poésie, style de peinture, musique et danses folkloriques. Les Ragas classiques de l’Inde représentent un accomplissement majeur dans le domaine des arts, développés depuis des siècles par le pays et son peuple. Le style varie entre ceux du nord et ceux du sud, mais les principes de base ainsi que les théories du système sont enrichies par des idées venant du nord et du sud. Les Ragas sont habituellement définis comme Marga Sangeeta, chants cosmiques ou musique éternelle, alors que la musique folklorique traditionnelle s’appelle Deshi, autrement dit venant de la terre. L’un est national tandis que l’autre est régional.

Même un Européen de bonne culture générale peut être désemparé par la diversité des langues et dialectes en Inde. Il compare le pays avec l’Italie s’il est italien ou avec la France s’il est français. S’il pouvait concevoir l’Inde comme un continent, avec son demi million de villages et ses trois mille grandes villes, qui réunissent la majorité des religions principales du monde, c’est-à-dire le Judaïsme, le Christianisme, l’Islamisme, l’Hindouisme et le Bouddhisme, il pourrait mieux approcher les structures sociales et culturelles de l’Inde. Depuis l’antiquité, l’Inde est la plus grande société pluraliste du monde de religion et de culture. Par exemple, les juifs de cochin se disaient être les premiers réfugiés politiques à atteindre l’Inde après la destruction du temple de Jérusalem en 70 après J.C. Les Zoroastriens parsis ont fuit vers l’Inde pour éviter les persécutions musulmanes aux 7e et 8e siècles.Ce pluralisme, qui pourrait être pris pour un manque d’uniformité, nous démontre une intégration, une unité dans une nation aussi, sans pour autant se référer à une doctrine totalitaire, la politique ou religieuse. En Inde, la religion n’est pas considérée comme une institution. Celle qui s’en approcherait le plus serait le bouddhisme qui, né en Inde pour gagner tout le pays, en a finalement disparu sans carnage ni violence. Tout cela a eu lieu pendant une période d’environ mille ans. Le bouddhisme est apparu pour alléger l’hindouisme qui se figeait, trop rigide dans ses formes et ses rites, et qui s’éloignait de la réalité. Le bouddhisme a su répondre aux aspirations apparues en Inde jusqu’à ce que l’hindouisme ait refait surface avec un nouveau souffle.

L’hindouisme, ou le Sanatan Dharma, qui est le terme employé en Inde, représente un mode de vie. Ce n’est aucunement une institution ayant un représentant suprême comme le Pape ou un Ayatollah.Pour un hindou, la compréhension du Brahma, l’Absolu, représente l’accomplissement spirituel suprême. Brahma est au-delà des formes, des sexes et des attributs, et on y fait référence en utilisant une appellation neutre au lieu de Il ou Elle. Brahma n’est ni bienfaisant ni malfaisant, mais omniprésent et donc ne peut être confiné entre les murs d’un temple. Dans un pays qui se consacre aux dieux, aux déesses et aux temples, Brahma est sans abri. Par contre, en commencant par Shiva, aux trois visages de la Trimurti, qui représente les forces de la création, la conservation et la destruction, il existe en Inde presqu’autant de Dieux et de déesses que de créatures. En passant par la dévotion, un symbole devient la Réalité même, puisque le Créateur et ses créations sont entièrement inséparables, et c’est ce concept qui a donné naissance aux chants de dévotion pour Dieu, le bien-aimé, que nous appelons chants mystiques dans le monde occidental.Le Sanatan Dharma (ou simplement le Dharma), implique chaque aspect de la vie, y compris les arts. Il existe donc une interaction parmi les arts mêmes, ainsi que dans leurs relations vis-à-vis de la vie. Un mode musical peut être exprimé en peinture et un tableau peut être traduit en strophes. Ce pluralisme se trouve dans chaque sphère d’activité de la vie. Tabous sociaux et des règles de conduites strictes n’ont jamais manqué, mais il a toujours existé un moyen psychologique de délivrance pour, à la fois, l’individu et la collectivité. De cette manière, une scène érotique peut être sculptée sur le mur d’un temple ou bien illustrée avec des couleurs vives sur un tableau miniature pour représenter graphiquement la sexualité. Si l’esprit et le corps font partie de la réalité, le sexe ne devrait pas en être exclu. Ceci explique comment les hindous anciens et traditionnels pouvaient accepter d’une part un code moral sévère, et d’autre part sa représentation ouverte dans les arts séculiers et religieux. Leurs habitudes sociales et leur expression artistique pourraient sembler se contredire, mais ils sont équilibrés grâce au Dharma. Ainsi, les hindous ont vécu ces deux attitudes sans compromis psychologique. En conséquence, on peut trouver dans plusieurs Ragas classiques et dans la musique folklorique une essence religieuse, en même temps que, dans la musique religieuse, l’univers varié de l’amour.

LA MUSIQUE ET LA DANSE

La musique et la danse traditionnelles de l’Inde se divisent nettement en deux espèces: une s’adresse aux élites, ceux qui ont reçu une éducation dans les arts et la philosophie de la musique et de la danse, et l’autre qui représente la terre, la musique et les danses populaires folkloriques est autant appréciée par la vue que l’ouïe et fait donc appel à une autre catégorie d’artistes. La musique et la danse en Inde, qu’elles soient de nature culturelle ou populaire, ne sont pas toujours en corrélation. Une danse peut être parfois accompagnée uniquement par des instruments à percussion, ou, parfois par des chansons et des instruments mélodiques. En Inde moderne, l’art de la musique et de la danse culturelle ou érudite est considéré comme un art “classique”. Il veut évoquer des sentiments définis, provoquer une certaine humeur ou un bien-être émotionnel, en passant par la voie du son “pur” de la musique et des mouvements chorégraphiques, sans l’armature du texte. Cette idée sera développée avec plus de détails plus loin.En Inde, la musique et la danse varient énormément selon l’Etat, comme les langues et les coutumes. Outre la musique et le style, les instruments peuvent varier aussi, bien que les instruments de village dans tout le pays se ressemblent à un certain degré en ce qui concerne leurs fonctions ou leurs traits de base, tels les luths et les vièles, les tambours et les cymbales, les flûtes..., selon la disponibilité des matières premières pour leur fabrication.

De manière générale, la musique indienne folklorique peut être divisée en deux catégories distinctes : la musique religieuse et la musique séculière. Celle-là est en rapport avec la dévotion tandis que celle-là couvre la vie réelle de tous les jours. A première vue, ces deux genres peuvent sembler être totalement indépendants l’un de l’autre mais, en vérité, ils ne font qu’un. Les chansons de dévotion racontent la vie journalière tandis que les chansons séculières dévoilent la recherche spirituelle. Ceci dit, il existe des exceptions. Les danses folkloriques, qui sont moins élaborées que leurs consoeurs classiques, peuvent, également, être religieuses ou bien séculières. Elles peuvent être exécutées par une ou plusieurs personnes, l’occasion peut être collective ou non. Les danses villageoises ont tendance à suivre une forme ronde, afin de former une chaîne qui serpente dans un cercle fixe lors d’une danse de communauté. Ces danses sont habituellement accompagnées par des chants et des instruments. Les événements les plus propices pour ces danses circulaires à grande échelle apparaissent à la fin des récoltes et aux mariages, comme partout dans le monde.Contrairement à la musique et à la danse folklorique, qui révèlent les milieux culturels et linguistiques différents, les Ragas classiques représentent l’Inde entière. Dans les Ragas classiques, l’émotion et l’intellect sont le sujet d’une étude consciente, chacun jouant un rôle important. La racine du mot Raga exprime les différentes nuances de la passion : la dévotion, le désir, l’amour, la jalousie et la colère. Il représente, également, la couleur rouge ainsi que le mode dans la musique de l’Inde. En Europe, pendant le Moyen Âge, plusieurs modes étaient utilisés, de la même manière, en Inde, il existe de nombreux Ragas principaux, et d’autres secondaires. La gamme du mode dorien est identique à Bhairavi, un Raga féminin, s’appelant Ragini. Les Ragas secondaires sont connus sous le terme, Raginis. Le Sangeeta Ratnakara, une oeuvre en sanskrit ancien, décrit le Raga comme “une forme particulière du son dans laquelle les notes et les sections mélodiques servent d’ornements”. Ailleurs, il est défini comme “un arrangement de sons, qui se compose de sections mélodiques, agréable aux sens”. Un spécialiste occidental l’a dépeint comme suit :“C’est une œuvre d’art où sont intimement mêlés, le temps, la vue, les couleurs, les saisons, l’heure”.Un Raga n’est pas uniquement la base mélodique dans la musique indienne, ni simplement une oeuvre d’art. De même que Dharma peut être l’âme qui réunit les mœurs et les croyances hindous, le Raga réunit le visuel avec l’auditif, la passion avec l’indifférence.

LA PHILOSOPHIEET LES SOURCES DU SON

La philosophie et la religion en Inde sont basées sur la conception de l’Infini dans l’énergie concentrée du Fini, comme on peut souvent le constater dans la littérature, la peinture et la musique. La musique indienne et les représentations artistiques se concentrent sur une émotion particulière à la fois. Ceci est nommé le Rasa, dont les neuf parties expriment les arts : l’amour, le rire, le pathétique, l’héroïsme, la colère, la peur, le dégoût, l’émerveillement et la paix. Chacune est développée avec le support des émotions mineures qui peuvent l’accompagner. Ceci est une différence fondamentale par rapport à la musique occidentale moderne, où on trouve des humeurs diverses et parfois opposées dans le même thème.Les spécialistes de la philosophie de la musique indienne, appellent la musique le Nadaveda, la connaissance du son. Un texte sanskrit de Sarada Tilak proclame que le son est l’expression de l’Energie Suprême, le résultat de la vibration transcendante. L’essence du son est symbolisée par la syllabe AUM. Pour un hindou, AUM symbolise, outre l’énergie qui émet le son, la création, la préservation et la dissolution. C’est une combinaison de trois sons : “A”, “U” et “Ma”, et chacun représente une des sources de la Triple-Energie : la Création, la Préservation et la Dissolution. AUM est aussi considéré comme l’essence des Vedas. Les Vedas, ou la Sagesse Eternelle, sont à la racine de la pensée, de l’art et de la musique indienne. Dans un monde de bruits, de murmures, de cris et de chansons, les théoriciens indiens du son ont inventé la syllabe, AUM, afin de résumer tous les sons et tous les temps.

La philosophie du son a tenu une place de haute importance dans les oeuvres anciennes réalisées sur la musique. Deux sortes de sons musicaux existent : l’un est nommé le ANAHATA, ou “non-frappé”, il s’agit d’une vibration ou d’un son que le musicien entend en lui-même avant de le transmettre par un instrument ou une voix; l’autre est le AHATA, “frappé”, qui suit la vibration de l’air.

Il y a cinq catégories de sons frappés, qui se produisent par :

• Les ongles qui administrent des coups sur les cordes, c’est à dire les instruments à cordes pincées, tels que le Vina, Surbahar, etc. (cf. Ragas sur les Instruments à Cordes), ainsi que d’autres instruments à cordes, ou à cordes et à archet.

• Vent (instruments à vent ou à anche, tels que la flûte en bambou, le Shahnai, etc.).

• La peau (les tambours, tels que le Tabla, le Pakhawaj, le Duggi, etc.).

• Métal, instruments à percussion, cymbales, cloches...

• Le corps (la voix, le chant. Cf. Deux Siècles de Chansons de Salon).

Bien que tous les instruments indiens soient dérivés des sources mentionnées ci-dessus, leurs structures sont si nombreuses et variées qu’il faudrait un temps infini pour les décrire. Cependant, ce coffret permet une initiation aux aspects les plus significatifs de la musique indienne actuelle, et sera ultérieurement suivi par d’autres évoquant les univers variés de la musique indienne.

LA TECHNIQUE

La musique indienne comporte trois octaves : une basse, une moyenne et une haute, et dans chacune il y a sept notes, comme dans le système de solfège. Chaque note indienne a un nom syllabique, la première syllabe du nom complet correspondant à son origine. Ces notes sont Shadja, Rishabha, Gandhara, Madhyama, Panchama, Dhaivata et Nishada. Ici, néanmoins, nous nous contenterons des équivalents européens (Do, ré, mi...) bien qu’un ton fixe n’existe pas en Inde.Dans la musique indienne, l’octave est encore divisée en vingt-deux Shrutis ou intervalles au nord et en vingt-quatre au sud. Les intervalles sont fixés par rapport les uns aux autres, et en utilisant le Do comme note tonique. Le musicien peut commencer son Do tonique sur n’importe quel intervalle des octaves pourvu qu’il suive les rapports entre les Shrutis. Comme je l’ai déjà indiqué, il n’y a pas de ton fixe dans la musique indienne, mais, l’importance est donnée aux groupes fixes de Shrutis ou les intervalles, qui sont attribués aux différents Ragas.Les vingt-deux Shrutis, cependant, ne servent pas dans tous les Ragas. On pourrait les comparer à une grande variété de couleurs chez un artiste-peintre, chaque Raga ayant une gamme ou une palette de couleurs principales. Parfois, des notes ou des intervalles hors de la gamme sont utilisés comme décorations mélodiques, mais on s’en sert avec la plus grande discrétion. En commençant par l’Alap, le prologue d’introduction, joué au tempo lent, le Raga ou la Ragini (la contrepartie féminine) se développe en passant par quatre phases. La première, dénommée le Sthayi, instaure le Raga, et se répète après chaque phase de celui-ci. La deuxième et la troisième phases, l’Antara et le Sanchari participent dans son développement, et servent de liens entre la première phase et la quatrième, l’Abhoga qui est en conclusion.

Le rythme, appelé le Tala, est un des éléments fondamentaux dans la musique indienne. Lorsque plusieurs instruments jouent ensemble, le tambour donne la tonique avec laquelle les autres instruments se mettent en accord. Le tambour, dit-on, est le roi des instruments. Il a été fabriqué par Brahma, le Créateur, afin d’accompagner la danse céleste qui suivait la victoire de Shiva auprès du démon, Tripurasura. Selon la légende, Brahma aurait créé le corps du premier tambour avec la terre mouillée par le sang du démon. Ceci explique le nom du tambour indien le plus ancien, le Mridanga, ce qui signifie “corps de terre”. Il est devenu, par la suite, un tambour à deux faces, en forme de cylindre en bois qui s’appelle le Pakhawaj. Le Tabla d’aujourd’hui a été mis au point en divisant le Mridanga et le Pakhawaj en deux. Le corps en bois est utilisé pour le Tabla de la main droite, et le corps en argile pour le Banya, qui est parfois aussi en métal. Le Tabla émet une frappe vive et le Banya donne un son grave et mat. Le mot Tabla, qui vient de l’arabe, “Tabl”, est un terme générique pour les tambours, et a été introduit dans l’Inde vers la fin du règne musulman.Les formes des tambours varient selon les besoins de la représentation. Les faces sont recouvertes de peau et l’on y trouve une pastille noire de forme circulaire qui se compose de pâte de riz bouilli mélangée avec de la poudre de fer, et qui est fixée d’une manière permanente sur la peau. Ceci aide à contrôler la hauteur des sons produits par le tambour. Des noms onomatopéiques sont donnés aux différentes frappes sur les tambours. Par exemple, en rythme Tritala, les seize sons, qui sont divisés en quatre parties, s’appellent : Ta Dhin Dhin Ta / Ta Dhin Dhin Ta / Ta Tin Tin Ta / Ta Dhin Dhin Ta /.Habituellement, trois vitesses de tempo sont utilisées dans le tambourinage : rapide, moyen et lent. Parfois un tempo à double vitesse est employé également. Un rythme est divisé en trois parties principales : la première frappe qui annonce un rythme s’appelle le Sama, les sons qui suivent sont les Tala ou les Tali, et puis le Khali qui est un son dans le vide est exprimé par un mouvement de la main.Tout comme les Ragas, de nombreux Talas existent, et tout ce qui est musique instrumentale, chansons ou danses sont inséparables des rythmes ou des Talas. On dit que chaque être vivant, tout comme la terre et les planètes bougent grâce au rythme.

REPRÉSENTATIONS VISUELLES DES RAGAS

Dans la musique indienne, chaque Raga ou Ragini possède une forme iconographique, ou visuelle en plus de sa forme tonale. Certaines écoles de peinture indienne les ont interprétés selon leurs propres idées. Dans une tentative d’accorder des principes unifiants entre les peintures, les Ragas et les Raginis. Des couleurs spécifiques ont été attribuées aux notes différentes, mais les artistes n’ont pas toujours suivi les règles de façon rigoureuse. Néanmoins, il est intéressant de constater que pour le Do, la tonique décisive par rapport aux intervalles ou les Shrutis, il n’a pas été attribué une couleur particulière; par contre, on lui accorde la qualité d’une couleur, par exemple l’incandescence des pétales de lotus. Le Ré est de couleur tannée, le Mi est doré, le Fa est blanc, le Sol est de couleur sombre, le La est jaune et le Si est un mélange de toutes les couleurs.Les tableaux ici reproduits représentent un Raga pour la saison de pluie qui s’appelle Megha Mallar (CD 1, planche 2) et Bhairavi, qui est un Ragini pour le matin (CD 1, planche 2). Ce sont des tableaux miniatures. Le Raga Magha Mallar vient de l’Ecole Bundi à Rajasthan (1675) et le Bhairavi Ragini, de l’Ecole Deccan (1700). Ce dernier, comme d’autres tableaux Ragamala, est en mode matinal, personnifié par Bhairavi priant son Seigneur Bhairava dans un temple. Elle joue des cymbales pour le réveiller. L’expression mélodique de Bhairavi est transmise par sa dévotion pour Bhairava. Par la note principale, ou le Vadi, de Bhairavi (le Do), l’artiste insiste sur un fond jaune. Le jaune correspond au La, ce qui représente la dévotion et l’ascétisme. La description de Bhairavi dans un vers en sanskrit indique qu’on a tenté de donner une forme visuelle standard aux Ragas et aux Raginis : “Sur un siège en cristal sur le sommet de la montagne Kailasa, Bhairavi vénère le grand Seigneur avec des fleurs de lotus”. Les poètes la décrivent avec des cymbales en main. Elle a le teint jaune et de grands yeux, et elle est l’épouse de Bhairava.Bhairavi n’est qu’un exemple parmi les nombreux Ragas et Raginis. La richesse dans l’art indien ne provient pas uniquement par son accomplissement artistique, mais également de sa capacité unique à lier les différentes formes artistiques, et à les intégrer dans la vie et la religion.

RAGAS AVEC DES INSTRUMENTS A CORDES

CD 1

La musique traditionnelle en Inde peut être divisée en trois familles : a) L’art étudié de faire de la musique en utilisant le système de Raga à base de gammes, comme décrit précédemment, b) Les chansons de communauté et la musique de danse des villages, qui ont été transmises d’une génération à une autre, et c) La musique largement variée des indigènes, où la nature et les éléments tiennent un rôle important. Ce coffret comporte deux CDs; un avec des Ragas de nature contemplative, et l’autre avec des chansons de base de Raga, qui ont comme but, la dévotion et le divertissement.

Les instruments à cordes, le vina et le surbahar, que l’on y trouve, appartiennent au système de Raga, qui est une forme artistique qui a été développée d’une manière intentionnelle, et qui est soutenu par une grande quantité de littérature sur la théorie et la pratique d’une sorte de musique où les émotions et l’intellect sont tous deux sujets d’une investigation artistique. Le mot Raga, qui signifie, “ce qui plaît”, représente les diverses expressions de la passion : l’amour, le désir et la dévotion. Le mot Vina, qui a été employé dès 1000 Av J.C. dans le Yajurveda, est le terme général pour les instruments à cordes. Une variation du Vina, qu’on peut entendre dans ce CD s’appelle le Rudravina. Il s’agit d’une cithare utilisée dans les Ragas de l’Inde du nord, et qui comporte deux grandes courges de résonance. Le Surbahar, par contre, a fait son apparition au début du 19e siècle. C’est un instrument à cordes pincées de provenance de l’Inde du nord, et qui est un Sitar grave aux dimensions plus importantes. Il se joue avec un plectre en acier qui est porté sur l’index. Il comporte un manche d’une longueur de 115 cm et d’une largeur de 12 cm. Il a une planche avec 17 frettes métalliques. Il y a sept cordes pour la mélodie et le bourdon d’accompagnement, tandis qu’un jeu de 11 cordes qui vibrent par résonance provoque un ronflement doux.

1. Todi. Mode féminin. Raga pour la matinée. Le Vadi, ou la note dominante et le Dha-komal (La bémol), et son Jati, ou sa classe, est le Sampurna, ce qui veut dire “complet”, et qui est de sept notes. La couleur du Raga est Pingala, ou mordoré. Il exprime le soleil et l’espoir, avec un grain de sévérité et de force. Il est tendre et affectueux, mais porte certains sentiments tristes. Il est interprété au Surbahar par feu Amiya Gopal Bhattacharya, originaire du Bengale Occidental, professeur de musique à Varanasi et créateur de spectacles à Uttar Pradesh et au Bengale Oriental. Enregistré à Varanasi, 1968. 28.30 minutes.

2. Miyan-ki-Malhar. Mode masculin. Raga pour la saison des pluies, mais peut également se jouer à minuit. La note dominante, ou le Vadi, est la Ma ou le Fa. Il se sert de sept notes dans sa gamme ascendante, et six en descendante. Il exprime les pluies, la croissance, en étant autoritaire et joyeux. Ici, il est joué sur le Rudravina par feu Jyotish Chandra Chowdhury, qui était également d’origine du Bengale Occidental, et qui enseignait la musique à l’Université Hindou de Varanasi. Il donnait des concerts publics et non-commerciaux. Enregistré à Varanasi, 1954. 7.00 minutes.

3. Bihag. Mode indéterminé. Il utilise cinq notes dans sa gamme ascendante et sept en descendante. La note dominante et le Ga (Mi). Un Raga de soir, qui exprime les émotions contrastantes d’amour et de déception qui sont ressenties dans le calme nocturne. Il est interprété également au Rudravina par Jyotish Chandra Chowdhuri. Enregistré à Varanasi, 1954. 7.00 minutes.

4. Bhairavi. Mode féminin. Raga du matin. Il utilise sept notes dans sa gamme ascendante et descendante, avec le Sa (Do) comme note dominante. Aussi brillant que les pétales de lotus, Bhairavi exprime la tendresse et la dévotion. Interprété également au Rudravina par Jyotish Chandra Chowdhuri. Enregistré à Varanasi, 1955. 10.40 minutes.

DEUX SIÈCLES DE CHANTS POUR SALONS DE MUSIQUE

CD 2

Le Bengale est le pays du peuple de la langue bengali et qui se compose d’environ 250 millions d’habitants. La nouvelle nation du Bangladesh, créée politiquement en 1971, était auparavant la partie orientale du Bengale. Elle a été séparée du reste de l’Inde lors de la partition du sous-continent par la Ligue musulmane en 1947 entre le Pakistan musulman - alors oriental et occidental - et l’Union indienne. Les habitants, de manière générale, sont extrêmement fiers de leur musique et de leur langage : le bengali.Les chansons incluses dans ce disque appartiennent à la tradition bengali de la musique cultivée, avec des paroles écrites dans les derniers deux siècles par des compositeurs renommés tels que Rammohan Roy, Dwijendralal Roy, Nidhubabu, Rasikchandra, Rajanikanta, Nishikanta, Gobinda Adhikari, Rabindranath Tagore et Najrul Islam. Habituellement la musique n’est pas écrite dans ces régions, mais ces grands paroliers ont également composé la musique pour leurs chansons, mélangeant parfois les Ragas avec des airs folkloriques du Bengale Occidental et Oriental. Certaines chansons sont occasionnellement chantées avec la musique de Raga pur, mais en général, peu d’ornements mélodiques sont employés. Les chansons ont été composées pour les cours, les salons de musique d’anciens propriétaires opulents, et les connaisseurs. Les compositeurs et les chanteurs, des deux sexes, venaient du Bengale Occidental et Oriental, le chant est considéré comme l’héritage commun des bengali.Les chansons de ce CD ont été choisies et interprétées par feu Himaghna Roy Chowdhury et ont été enregistrées en novembre 1972 lors d’un concert public à Calcutta. Dans cet enregistrement, il a été accompagné par les musiciens suivants :Chandra Sekhar (à l’Esraj, une vièle à manche long avec quatre cordes mélodiques et onze cordes qui vibrent par résonance), Haren Manna (au Tabla), Kamal Mallik, Kedar Nandi et Rabin Mukherji (au Sitar, harmonium et cymbales). Le chanteur lui-même joue le Tambura.

LES CHANSONS

1. Mon eki bhranti tomar -

par Raja Rammohan Roy

Un chant de dévotion, “Comment peux-tu faire l’erreur, mon cœur, d’accueillir et de quitter Dieu, alors qu’il est omniprésent”. 2.35 minutes.

2. Ki swadeshe ki bideshe -

par Raja Rammohan Roy

Un chant de dévotion, “A la maison, ou à l’étranger, je vis où je peux, mais je te vois partout dans ta création. A chaque moment ta gloire s’annonce dans l’espace et le temps sans fin, et je te vois partout”. 2.15 minutes.

3. Malay asiya koye gechhe kane -

par Dwijendralal Roy

Un chant d’amour, “La brise du sud m’a murmuré, ma bien-aimée, que tu me rendras visite afin d’apaiser mon cœur assoiffé et angoissé. Tu arriveras sous peu. Les étoiles, les planètes et le ciel bleu signalent vivement ta présence proche. Une flamme s’allume au fond de mon cœur, je sais que tu m’aimeras cette fois-ci...”. 3.10 minutes.

4. Bhalobeshe bhalo kandale -

par Nidhubabu

Un chant d’amour, “ En m’aimant, tu m’as donné de belles larmes, délicieusement étrange! Comment peux-tu te garder à distance pendant que je me noie? Je souffre en t’aimant, et toi tu restes immobile avec ton cœur de pierre”. 2.35 minutes.

5. Mon je Nilo -

par Nidhubabu

Un chant d’amour, “Celle qui a emporté mon cœur ne me l’a jamais rendu, et ma vie a disparu sans que je la revoie. La première fois que je l’ai vue, j’ai juste contemplé son visage. Je voulais parler mais ma bouche ne s’ouvrait pas. La nuit, je la vois dans mes rêves et je lui tends mes bras sans l’atteindre”. 4.00 minutes.

6. Ay ma sadhan samare -

par Rasikchandra

Ces paroles appartiennent à la tradition bengali des chansons de dévotion dédiées à Kali, la déesse des Temps. Dans celle-ci, Kali est appelée la mère divine qui représente l’esprit du temps - le temps qui dévore tout ce qui est pourri ou maléfique, et pourtant qui donne naissance à de nouvelles vies. Parfois les paroles de ces chansons expriment l’action de se rendre, et parfois le défi, comme dans celle-ci. “Engageons-nous, Mère, dans la guerre pour découvrir qui est le perdant, la mère ou le fils. J’ai la dévotion comme chariot de bataille, l’amour et la vénération pour chevaux”. 3.45 minutes.

7. Tomar deoya prane -

par Rajanikanta

Un chant de complainte, “Si tu m’as donné la vie, les chagrins étaient aussi un cadeau de ta part, et puisque je te sens dans mon cœur, je sais que lui aussi est à toi...”. 2.50 minutes.

8. Shunya e buke -

par Najrul Islam

Une chanson d’amour, “Mon cœur vide attend ton retour, enfant, reviens. Depuis que tu t’es envolé, les fleurs se flétrissent à l’aube, la lune est devenue pâle et, de tristesse, la rivière déborde de larmes, en scrutant le ciel. Les forêts se remettront à rayonner de fleurs quand tu reviendras et le ciel sera bleu dès que tu le regarderas”. 4.05 minutes.

9. Tomar andhar nisha -

par NishikantoUne chanson de dévotion, “Ta nuit de ténèbres soulève ma tristesse, me touche avec une pierre de philosophe. L’obscurité du pathétique brille comme le soleil levant, et la douleur s’envole. Ta captivité devient la liberté comme l’hiver annonce le printemps. Les bourgeons de la souffrance se réjouissent comme des fleurs quand les clôtures sont forcées par ta vitesse sans limites” 3.10 minutes.

10. Mahasindhur opar theke -

par Dwijendralal Roy

Une chanson de dévotion, “Venant de l’autre rive de la mer de la vie, une chanson pénètre mes oreilles, comme un murmure d’amour et d’unification. Elle m’appelle vers un pays de vie éternelle, où l’air vibre des chansons de printemps et où la terre est verte sous le ciel éclairé par la lune”. 3.45 minutes.

11. Shyam kandano bhalo noy -

par Gobindo Adhikari

Ceci est une chanson de conseil de dévotion, sur le thème de Krishna et Radha, sa bien-aimée. Le poète conseille à Radha à mettre son orgueil de côté afin d’être avec Krishna, son bien-aimé. 6.00 minutes.

12. Bujhi oi sudure -

par Rabindranath Tagore

Un chant méditatif, “ J’entends l’appel d’un monde lointain dans la brise du soir. Mon cœur, distraitement, ouvre la porte afin de libérer les liens joueurs de la vie...”. 2.00 minutes.

13. Shaon ashilo phire -

par Najrul Islam

Une chanson de moisson, “Le mois des pluies est revenu, mais pas lui. Les pluies partiront mais pas mon espoir. Ne me demande pas de porter ma jupe de couleur de maïs ni mon voile qui ressemble à un nuage. Le nuage pourrait trouver son chemin dans le ciel peint de kôhl, mais pourrait-il trouver son chemin pour me revenir? ” 7.15 minutes.

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA

Adaptation par Laure WRIGHT

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS SA, 1997

Remerciements à Maggie Doherty, Patrick Colléony, Suri Gopalan.

english notes

FOREWORD

India, like the Continent of Europe, has within its geographical orbit widely varying landscapes and climates as well as nearly a billion peoples of different ethnic origin. Separated from the rest of Asia by the Himalaya, it is a virtual sub-continent. Spreading over an area of 3 287 782 sq. kilometers, India, as a Democratic Republic, has within its union seven centrally administered territories as well as twenty-five self-administered States, each with its own language and literature, poetry and painting, folk music and dances. On the other hand, the classical Ragas of India represent one of the most important achievements in the field of the arts, developed over many centuries by the country and its people as a whole. The details of the north Indian style of performance differ from those found in the south, but the basic principles and the theories that govern the system are enriched by contributions from the North as well as the South. While the Ragas are traditionally defined as Marga Sangeeta - cosmic songs, or eternal music - music of the folk traditions or of the people is known as Deshi, of the land. One is national and the other regional.Even a fairly well informed European is bewildered by the many different languages and dialects of India. Presumably he compares India with Italy if he is an Italian, or with France if he is a Frenchman. If he could visualize India as a continent, having more than half a million villages and over three thousand cities - housing most of the major religions of the world, namely, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism, he would find it easier to understand the social and cultural structures of India. As a matter of fact India consists of the largest pluralistic society of the world in religion and culture since ancient times. For instance the Cochin Jews claim to be the earliest political refugees to reach India following the destruction of the temple of Jerusalem in 70 AD. The Parsee Zoroastrians of Iran fled to India from Mohammedan persecution in 7th and 8th centuries.

This pluralism, or apparent lack of uniformity, brings us to the question of integration, the factor that gives a nation of such widely varying peoples a sense of unity without their being subjected to a totalitarian philosophy of politics or religion. Religion as an institution does not exist in India. Its nearest equivalent could be said to have been Buddhism which grew in India, spread from one end of the country to the other, and then slowly disappeared from its homeland without any bloodshed or violence. All this happened within approximately one thousand years. Buddhism came as a rejuvenating force to the decaying Hinduism which at the time was merely getting into a rut, rigid in its forms and formalities, losing all touch with reality. Buddhism fulfilled a great need in India until Hinduism revived itself with renewed vigour.Hinduism, or Sanatan Dharma as it is known in India, is a way of life. It is not an institution. It has no supreme representative like the Pope, or even an Ayatollah . For a Hindu, the understanding of Brahma, the Absolute, represents the supreme spiritual achievement. Brahma is beyond shape, sex or attributes, therefore, referred to as That, and not “He” or “She”. Brahma is neither benign nor malignant, but all pervading, therefore cannot be housed within the bounds of a temple. In a country wholly occupied with gods, goddesses and temples, Brahma is without a roof. On the other hand, starting from the Shiva’s Triple-feature that represents the forces of Creation, Preservation and Dissolution - there are almost as many gods and goddesses in India as there are peoples. A symbol becomes the Reality itself through devotion since the Creator and the created are wholly inseparable - a concept that has brought about the growth of devotional songs for God the beloved, known as mystical songs in the Western world.Sanatan Dharma, or Dharma in short, involves every aspect of life including the arts. Therefore there is interaction among the arts themselves as well as in their relationship to life. A musical mode can be painted, and a painting can be translated into verse form. This is pluralism, stretched to its very limits in every sphere of life. There has never been any shortage of social taboos, strict laws of moral behavior, but there was always scope for the psychological release for all, both individually as well as collectively. Thus an erotic scene could be sculpted on a temple wall or illustrated with vivid colours on a miniature painting to present the facts of life graphically. If the human mind and body are parts of reality, then sex is not removed from it either. The ancient and the traditional Hindus, therefore, were able to accept, on one hand the strict social laws and codes of behaviors, and on the other a frank and open expression through religious and secular arts. The social habits and the expression of the arts, apparently contradictory, were complemented by the balancing force of the Dharma. It helped the Hindus to accept both these attitudes without having to make a psychological compromise. Therefore, in many classical Ragas as well as in folk music, there is frequently a religious flavor, and, in religious music, the varied universe of love.

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS SA, 1997

MUSIC AND DANCE

The traditional music and dance of India are of two distinct types : One for the elite, for those who are educated in the arts and philosophy of music and dance, either for performing or for listening and viewing and the other represents the land, the popular form of music and dance, belonging to folk traditions. Whether cultivated or of popular nature, music and dance in India are not always interrelated. Sometimes a dance can be accompanied only by the percussion instruments and at other times with songs and melody instruments. The cultivated or the learned arts of music and dance, in modern India, are referred to as “classical” music and dance. Their purpose is to evoke certain feelings, conjuring up a predestined mood, an emotional content, through “pure” musical sound and dance movements, without having to depend on the words of a lyric or a dramatic tale. We will present this matter in detail later on disc No. 1, step by step, as we advance. As with languages and customs, the folk music and dance of India vary a good deal from State to State. In addition to the music and the style of presentation, the instruments differ too although most village instruments throughout India have a certain similarity of function or basic features such as those of lutes and fiddles, drums and cymbals, flutes, shawms and so on, depending on the availability of raw material for making instruments. Broadly speaking, Indian folk music can be described as being of two distinct varieties: religious and secular. The one is connected with devotion and the other with the environment of everyday life, with flesh and blood. Though on the surface these aspects of folk music may seem quite independent of one another, basically they are fused into one. The devotional songs deal with everyday life just as the secular songs reveal spiritual seeking.

This seems to be the general tendency, but there are exceptions too. Similarly, the folk dances, much less elaborate than their classical counterparts, can be religious as well as secular. These can be performed by one or by many depending on the occasion which too can vary at being religious or secular, individual or collective. In form, village dances tend to be round, so as to revolve in chain formation, winding in and out of a fixed circle when it comes to represent a community dance. The musical accompaniments for folk dances are usually provided by voice and instruments. End of harvest as well as weddings in the village appear to be the most popular seasons for such large scale circular dances, as elsewhere in the world. Compared with the folk music and dance, which reveals the varied cultural and linguistic backgrounds, the classical Ragas can be safely described as an art representing the whole of India. In the classical Ragas, the emotions and the intellect are subjects for conscious study. They both play important parts in the execution of a Raga. The root meaning of the word Raga expresses various shades of passion: devotion, desire, love, envy and anger. It also denotes the colour red as well as the mode in Indian music. Just as in Europe in the middle ages there were several modes in use, so in India there are a number of principle Ragas, as well as secondary ones. The scale of the Western Dorian mode is identical to Bhairavi, a feminine Raga, called Ragini. The secondary Ragas are known as Raginis. Sangeeta Ratnakara, an ancient Sanskrit work on music, describes a Raga as “a particular form of sound in which notes and melodic sections are used as ornaments.” Elsewhere, it is defined as “an arrangement of sounds, which possesses melodic sections gratifying to the senses...” A Western scholar describes it as:“A work of art in which the time, the song, the picture, the colours the seasons, the hour, and the virtues are so blended together as to produce a composite production...”A Raga is not only the basis of melody in Indian music, nor merely a work of art. If Dharma can be described as the integrating spirit among the varied ways of Hindu life and faith, Raga integrates the visual with the aural, passion with detachment.

THE PHILOSOPHY AND THE SOURCES OF SOUND

The conception of the Infinite in the concentrated energy of the Finite is the basis of Indian philosophy and religion, and we see it often expressed in our literature, painting and music. Indian music and the performing arts concentrate on one particular emotion at a time. This is called Rasa and there are nine of them expressing love, laughter, pathos, heroism, wrath, fear, disgust, wonder and peace for dramatic exploitation. Each Rasa is developed and cultivated along with the minor emotions that support it. This is where Indian music differs fundamentally from modern western music which changes and contrasts its moods within a given theme.Scholars of Indian music-philosophy refer to music as Nadaveda, the knowledge of sound. The ancient Sanskrit text of Sarada Tilak says that sound is the expression of the Supreme Energy, the result of the elemental vibration. The essence of sound is symbolised by the syllable AUM. To a Hindu, the syllable AUM not only symbolises the energy that produces sound, it symbolises creation, preservation, and dissolution. It combines three sounds: “A” , “U” and “Ma”, each representing one of the sources of the Hindu Triple-Energy - Creation, Preservation, and Dissolution. AUM is considered to be the essence of the Vedas too. The Vedas, the Eternal Wisdom, are the root of all Indian thought, art and music. In a world of noise and murmur, shouts and songs, the Indian theorists of sound had devised the syllable AUM, the synopsis of all sounds at all times.In the ancient works on music, the philosophy of sound is given a very important place. Musical sound is said to be of two kinds: one is called ANAHATA - unstruck - a vibration which in the present context could be described as the sound which the musician hears within himself before transmitting it through an instrument or voice; and the other is AHATA - struck- produced by the vibration of the air.Struck sounds are of five kinds. These are produced by : 1. Finger nails implying strokes against strings, i.e., plucked stringed instruments, viz., Vina, Surbahar, etc. (cf. Ragas on Stringed Instruments), as well as all other types of stringed and string and bow instruments. 2. Wind (wind and reed instruments, viz. bamboo flute, Shahnai, etc.)3. Leather (drums, viz. Tabla, Pakhawaj, Duggi, etc.)4. Metal (metal percussion instruments, viz. cymbals, bells, discs, etc.)5. Body (voice, viz. singing, cf. Two Centuries of Music-Room Songs). Though all Indian musical instruments derive from the above-mentioned sources, their individual structures are so varied and rich that it is impossible to describe them all within the limited space of this essay. This album, however, offers an introduction to some of the most important aspects of Indian music today but this is to be followed by several others offering glimpses from the various universes of Indian music.

THE TECHNIQUE

There are three octaves used in Indian music. These are low, medium and high, and within each octave there are seven notes equivalent to the sol-fa system. Each of the Indian notes has a short syllabic name, the first syllable of the complete name denoting the origin of the note. They are: Shadja, Rishabha, Gandhara, Madhyama, Panchama, Dhaivata, and Nishada. We shall, however, confine ourselves here to the European equivalents such as C, D, E, F, G, A and B, though there is no such thing as a fixed key in Indian music.In Indian music the octave is further divided into twenty-two Shrutis or intervals in the North and twenty-four in the South. The intervals are decided in relation to one another and with C as the tonic. The musician can start his tonic C on any interval of the octaves as long as he follows the relationship of the Shrutis. As I mentioned earlier, there is no fixed key in Indian music; instead the emphasis is on fixed sets of Shrutis or intervals as attributed to different Ragas.Not all the twenty-two Shrutis, however, are used in every Raga. They are like a generous selection of colours in an artist’s studio, each Raga having a particular scale or palette of main colours. Sometimes, however, notes or intervals outside the scale are also used as melodic ornaments, but with great discretion and care. Beginning with the Alap, the introductory prologue in slow tempo, there are four phases in the development of a Raga or Ragini (the feminine counterpart of a Raga): the first phase, Sthayi, which establishes the Raga, is also repeated after every phase within the Raga. The second and third phase, Antara and Sanchari, help in developing a Raga and act as links between the first phase and the fourth concluding phase, Abhoga.

Rhythm, which is known as Tala, is one of the most important elements in Indian music. When several instruments are played together, the drum provides the tonic to which all the other instruments are tuned. The drum is said to be the king of all instruments. It was made by Brahma, the Creator, in order to accompany the celestial dance which followed Lord Shiva’s victory over the demon Tripurasura. Brahma is said to have created the body of the first drum with earth wet with the demon’s blood. That is why the name of the most ancient Indian drum is Mridanga, which means clay-body. This was later altered to a double-headed, barrel-shaped, drum of wood - carved out of a large piece of log- and called Pakhawaj. Today’s Tabla has been developed by splitting the Mridanga and the Pakhawaj in two halves - employing the wooden body for the right hand Tabla and the clay body for the Banya, which, sometime, is made of metal too. Tabla generates the sharp beats and Banya the dull and the deep ones. The word Tabla, having its roots in the Arabic “Tabl” which is a generic term for drums, was introduced towards the end of the Islamic rule in India.The shapes and sizes vary a great deal depending on the needs of a particular performance. The drum heads are covered with leather and a circular black patch made of boiled rice-paste mixed with grated iron dust, permanently fixed on the leather. It helps to control the pitch of the note produced by the drums. Different onomatopoeic names are given to the different strokes on the drums. For instance, in rhythm Tritala, the sixteen beats divided in four sections are called: Ta Dhin Dhin Ta | Ta Dhin Dhin Ta | Ta Tin Tin Ta | Ta Dhin Dhin Ta |.Usually three different tempi are used in Indian drumming. These are slow, medium and fast. Sometimes a double-fast tempo is used too. A rhythm is divided into three main sections: the first beat which opens a rhythm is called Sama, the beats which follow it are known as Tala or Tali, and then the empty beat, Khali, is expressed by a wave of the hand.Like the Ragas, there are a number of Talas too, and all instrumental music, songs and dances are inseparable from rhythm or the Talas. It is said that every living object as well as the earth and the planets move by rhythm.

VISUAL REPRESENTATIONSOF THE RAGAS

In Indian music each Raga and Ragini has an iconographc or visual form as well as a tonal form. Various schools of Indian painting have given their own interpretations. There was, however, an attempt to make a unifying principle in the paintings of Ragas and Raginis. Different colours were attributed to different notes, although the painters did not necessarily follow the rules rigidly. However, it is interesting to note that C, being the tonic in relation to which the intervals or Shrutis are decided, was not given a particular colour; instead it was given the quality of a colour, like the glow of the lotus petals. D is said to be tan-coloured, E gold, F white, G dark, A yellow, and B is a blending of all colours.The paintings reproduced in this album represent a seasonal Raga named Megha Mallar for the rains (CD-One, item 2) and Bhairavi, a Ragini for the morning (CD-One, item 4). These are miniature paintings. Raga Megha Mallar belongs to the Bundi School of Rajasthan, c. 1675, and Bhairavi Ragini to the Deccan School, c. 1700. In this, as in other Ragamala paintings, the early morning mode is personified by Bhairavi worshipping her Lord Bhairava in a temple. She is playing cymbals to wake her beloved lord. The melodic expression of Bhairavi is translated here through her devotion to Bhairava. Though the principle note or Vadi in Bhairavi is C, the artist seems to lay more emphasis on a yellow background. Yellow is the colour of the note A, representing devotion and asceticism. The following description of Bhairavi in a Sanskrit verse indicates that there was some attempt to give a standard visual form to the Ragas and Raginis: “On a crystal seat at Kailasa mountain peak, Bhairavi worships the great lord with lotus blooms.” The poets describe Bhairavi as having cymbals in her hands; she is yellow-complexioned and large-eyed and she is the consort of [Shiva in the form of] Bhairava.Bhairavi is only one example out of many Ragas and Raginis. The greatness of Indian art lies not only in its artistic achievement, but also in its unique ability to find a relationship between different art forms and to integrate them with life and religion.

RAGAS ON STRINGED INSTRUMENTS

CD - One

Traditional music of India can be divided into three broad groups: (a) The studied art of making music in scale-based Raga system as discussed earlier, (b) community songs and dance music of the villages, handed down from one generation to the other and then (c) the richly varied music of the aborigines in which nature and elements play an important role. This album consists of two CDs: One with Ragas of contemplative nature and the other with Raga based songs for devotion and entertainment.The stringed instruments Vina and Surbahar, presented in this CD, belong to the Raga system of music, which, as discussed earlier, is a consciously developed art form, backed by a remarkable quantity of literature on the theory and practice of music in which emotions and the intellect are subjects for artistic investigation. The word Raga - meaning that which pleases - represents various expressions of passion: love, desire and devotion that please the heart. The name Vina, first heard c. 1000 BC in the Yajurveda, is the basic Indian term for stringed instruments. A variation of the Vina that we are presenting in this CD is called Rudravina. It is the fretted stick zither of North Indian Raga music. It employs a couple of large round gourds as sound chests. The Surbahar, on the other hand, was introduced in early 19th century. This is a plucked stringed instrument of North Indian origin, constructed as a bass Sitar, but with much larger dimensions. It is played by a wire plectrum fitted to the index finger of the musician. This particular instrument has a neck which is 115 cm long and 12 cm wide. It carries a fingerboard with 17 metal frets. It has seven metal strings for melody and the accompanying drone while a set of eleven sympathetic strings vibrate with a soft hum when the instrument is played.

1. Todi. Gender: feminine. Raga for the early hours of the day. Vadi, or the dominant note is Dha-komal (A flat), its Jati, or class, being Sampurna, meaning ‘complete’, or of seven notes. The colour of the Raga is said to be Pingala, yellowish brown. Expression: sunshine and hope, with a touch of sternness and strength. Tender and loving, bearing a mixture of sad feelings. It is played on Surbahar by the late Amiya Gopal Bhattacharya who came from East Bengal and worked as a music teacher in Varanasi and gave public performances in Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. Recorded in Varanasi, 1968. 28.30 mins.

2. Miyan-ki-Malhar. Gender: masculine. Raga for the season of rains. but it is also played at midnight. The dominant note Vadi is Ma or F. In its scale it employs seven notes in ascent and six in descent. Expression: rains, growth, commanding and joyful. It is played here on Rudravina by the late Jyotish Chandra Chowdhury who too came from East Bengal and taught music in Hindu University of Varanasi and gave public performances at non-commercial concerts. Recorded in Varanasi, 1954. 7.00 mins.

3. Bihag. Gender: undefined. In scale it uses five notes in ascent and seven in descent. Dominant note Ga (E). An evening Raga, it is expressive of contrasting emotions of love and disappointment, felt through the stillness of night. This too is played on Rudravina by Jyotish Chandra Chowdhuri. Recorded in Varanasi, 1954. 7.00 mins.

4. Bhairavi. Gender : feminine. Morning Eaga. It uses seven notes in its ascending and descening scales, with the Vadi or the dominant note being Sa (C). Bright as lotus petals, Bhairavi expresses tenderness and devotion. Also on Rudravina, it is played by the late Jyotish Chandra Chowdhuri. Recorded in Varanasi, 1955. 10.40 mins.

TWO CENTURIESOF MUSIC-ROOM SONGS

CD - Two

Bengal is the land of the Bengali speaking peoples which includes the whole of Bengal, East and West, with a total population of about two hundred and fifty million. The new nation of Bangladesh, politically established in 1971, was formerly the eastern part of Bengal. It was separated from the rest of India when the sub-continent was divided under pressure from the Muslim League between the predominantly Muslim Pakistan - East and West - and India in 1947. East Bengal at that time was named East Pakistan, the eastern wing of the new Islamic State. West Bengal, on the other hand, joined the Republic of India. The inhabitants of Bengal as a whole, however, are intensely proud of their music and their language, Bengali,The songs presented in this album belong to the Bengali tradition of cultivated music, with words written during the last two centuries by well known song writers such as Rammohan Roy, Dwijendralal Roy, Nidhubabu, Rasikchandra, Rajanikanta, Nishikanta, Gobinda Adhikari, Rabindranath Tagore and Najrul Islam. Music, as usual in this part of the world is not written, but the lyrics were written by these great artists who also gave music to their songs, sometimes by blending the Ragas with folk melodies from the countrysides of East and West Bengal. Some of the songs at times are sung with pure Raga music but generally speaking, with limited amount of melodic ornamentations. The songs were made for the courts or the music-rooms of the rich landlords in the past, and for the connoisseurs. The writers and the singers, both male and female, came from East and West Bengal since the songs are accepted as the common heritage of the Bengali speaking peoples.The songs in this CD were selected and sung by the late Himaghna Roy Chowdhury and recorded in November 1972 during a public performance in Calcutta. In this recording he was accompanied by the following instrumentalists:Chandra Sekhar on Esraj, a long-necked fiddle, with four melody strings and eleven sympathetic strings. Haren Manna on Tabla, with Kamal Mallik, Kedar Nandi and Rabin Mukherji playing on Sitar, harmonium and cymbals. The Tambura was played by the singer himself.

THE SONGS

1. Mon eki bhranti tomar -

by Raja Rammohan Roy.

Devotional song: “How can you blunder, my heart, by welcoming or wishing farewell to God who is everywhere and ever present.” 2.35 mins.

2. Ki swadeshe ki bideshe -

by Raja Rammohan Roy.

Devotional song: “Either at home or abroad, I live wherever I can, but I see you everywhere amidst your own creation. As each moment declares your glory through endless space and time, I see you everywhere.” 2.15 mins.

3. Malay asiya koye gechhe kane -

by Dwijendralal Roy.

Love song: “The southern breeze has whispered in my ears, beloved, you will be visiting to remove the pain of my thirsty and anguished heart. You will be with me any time now. The stars, the planets and the blue sky are vivid with signs of your approaching presence. Lighting a flame in the core of my heart, I know you will be loving me this time...” 3.10 mins.

4. Bhalobeshe bhalo kandale -

by Nidhubabu.

Love song: “By loving me you gave me lovely tears of a strange delight! How can you stay aloof while I sink? As I suffer by loving you, you stay still as rock with heart of stone.” 2.35 mins.

5. Mon je Nilo -

by Nidhubabu.

Love song : “She who took my heart away, never gave it back and my life vanished for me without seeing her again. When I saw her first, I only gazed at her face. I wanted to talk but my mouth would not open. At night I see her in my dreams and as I stretch my arms, they fail to reach her.” 4.00 mins.

6. Ay ma sadhan samare -

by Rasikchandra.

These words belong to the Bengali tradition of devotional songs dedicated to Kali, the goddess of Time. In this, Kali is addressed as the divine mother, representing the spirit of time -time that devours all that is decayed and evil, and yet giving birth to new life. Sometimes the words of these songs express surrender and at other times challenge - as is the case wtih this song: “Let us engage, Mother, in an act of war and find out who is the loser, the mother or the son? Devotion is my battle-car with love and worship speeding as horses...” 3.45 mins.

7. Tomar deoya prane -

by Rajanikanta.

Devotional song: “If you have given me life, sorrows too are your gifts and as I feel you in my heart I know that too is yours...” 2.50 mins.

8. Shunya e buke -

by Najrul Islam.

Lament: “My empty heart awaits your return, my beloved child. With you flown away, blossoms at dawn wilt, the moon turns pale and the river in sadness is flooded with tears, scanning the sky. Forests will glow with flowers again when you are here and the sky will turn blue at a glance from you...” 4.05 mins.

9. Tomar andhar nisha -

by Nishikanto.

Devotional song: “Your night of darkness lifts my gloom brushing me with a philosopher’s stone. The blackness of pathos shines as the rising sun, losing all pain. Your bondage turns into freedom as winter heralds spring. The flower-buds of sufferings rejoice as blossoms when fences are forced open by your limitless speed.” 3.10 mins.

10. Mahasindhur opar theke -

by Dwijendralal Roy.

Devotional song: “From the other shore of the sea of life, a song enters my ears, like a whisper of love with an urge to unite. It calls me to a land of eternal life where the air is vibrant with spring-season songs and the earth is green below the moonlit sky...” 3. 45 mins.

11. Shyam kandano bhalo noy -

by Gobindo Adhikari.

This is a song of devotional advice, using the theme of Krishna and his beloved Radha. In this, the poet urges Radha to give up pride in order to be one with her beloved Krishsna. 6.00 mins.

12. Bujhi oi sudure -

by Rabindranath Tagore.

Nature song: “I hear the call of a distant world in tonight’s breeze. My heart absently opens the door to let free the playful bonds of life...” 2.00 mins..

13. Shaon ashilo phire -

by Najrul Islam.

Seasonal song: “The month of rains is back again but he did not come. The rains will go but not my hopes. Don’t ever ask me to wear my corn-coloured skirt and my veil that resembles the cloud. The cloud could find its way through the kohl-painted sky, but could he find his way to return to me...” 7.15 mins.

RECORDINGS, PHOTOGRAPHS & TEXT: DEBEN BHATTACHARYA

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS SA, 1997

Thanks to Maggie Doherty, Patrick Colléony, Suri Gopalan.

Ragas on stringedinstruments

CD - 1

1.Raga Todi on Surbahar 28.30

2.Raga Miyan-ki-Malhar on Rudravina 7.00

3.Raga Bihag on Rudravina 7.00

4.Raga Bhairavi on Rudravina 10.40

TWO CENTURIES OF MUSIC-ROOM SONGS

CD - 2

1.Mon eki bhranti tomar 2.35

2.Ki swadeshe ki bideshe 2.15

3.Malay asiya koye gechhe kane 3.10

4.Bhalobeshe bhalo kandale 2.35

5.Mon je nilo 4.00

6. Ay ma sadhan samare 3.45

7.Tomar deoya prane 2.50

8.Shunya e buke 4.05

9.Tomar andhar nisha 3.10

10.Mahasindhur opar theke 3.45

11.Shyam kandano bhalo noy 6.00

12.Bujhi oi sudure2.00

13.Shaon ashilo phire 7.15

CD Music of India Vol 1 © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)