- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

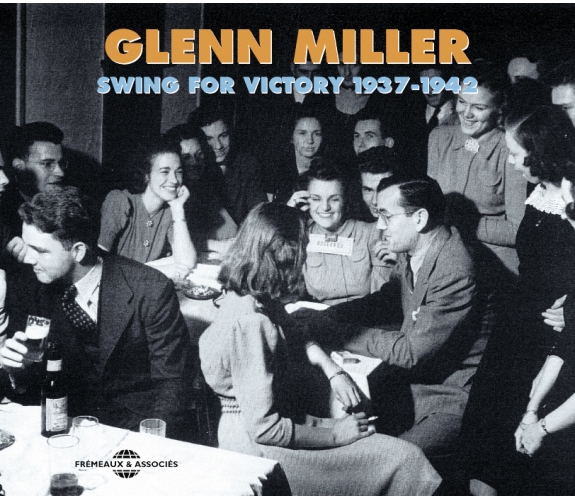

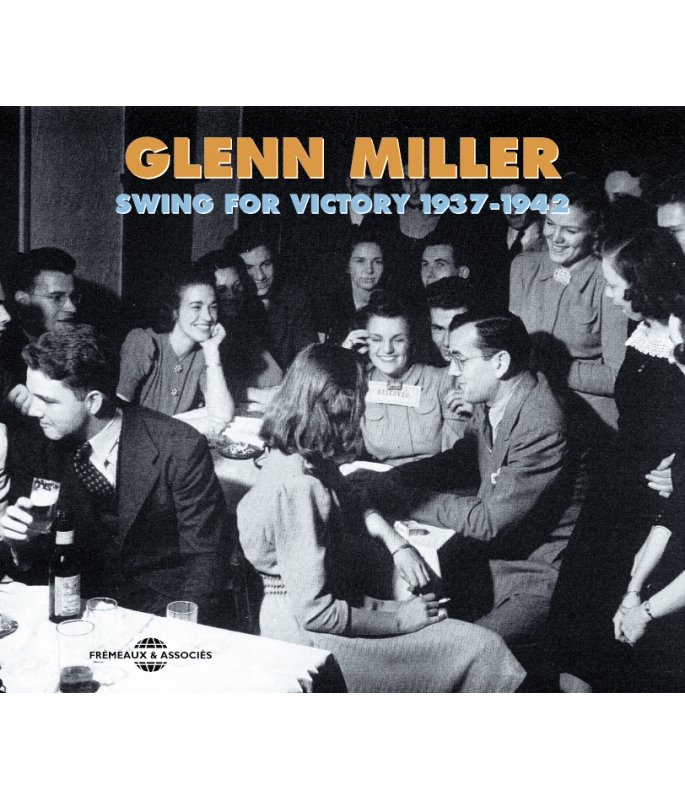

SWING FOR VICTORY 1937 - 1942

GLENN MILLER

Ref.: FA192

Artistic Direction : TONY BALDWIN

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 52 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

SWING FOR VICTORY 1937 - 1942

- - * * * * JAZZMAN

- - PLAYLIST TSF

- - RECOMMANDÉ PAR ÉCOUTER VOIR

- - RECOMMANDÉ PAR JAZZ NOTES

- - PLAYLIST TSF

- - SÉLECTION JAZZ HOT

- - SUGGÉRÉ PAR “COMPRENDRE LE JAZZ” CHEZ LAROUSSE

SWING FOR VICTORY 1937 - 1942

(2-CD set) Miller considered himself first and foremost a craftsman, and was content to leave weighty assessments of his artistry to the chattering classes. Includes a 48 page booklet with both French and English notes.

1943-1949 (coédition Mémorial de Caen)

ASCENSEUR POUR L’ÉCHAFAUD, A BOUT DE SOUFFLE, UNA...

DANSES DU MONDE - EUROPE ET AMERIQUE DU NORD, VOL....

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1RUG CUTTER S SWINGGLENN MILLERH HENDERSON00:03:041940

-

2PEG O MY HEARTGLENN MILLERF FISHER00:02:351937

-

3MOONLIGHT BAYGLENN MILLERGLENN MILLER00:02:351937

-

4DIPPER MOUTH BLUESGLENN MILLERJ OLIVER00:02:331938

-

5SOLD AMERICANGLENN MILLERGLENN MILLER00:02:551938

-

6KING PORTER STOMPGLENN MILLERJELLY ROLL MORTON00:03:301938

-

7MOONLIGHT SERENADEGLENN MILLERITCHELL PARISH00:03:281939

-

8RUNNIN WILDGLENN MILLERJ GREY00:02:491939

-

9GUESS I LL GO BACK HOMEGLENN MILLERW ROBISON00:02:461939

-

10SLIP HORN JIVEGLENN MILLERE DURHAM00:03:161939

-

11BLUE RAINGLENN MILLERJ VAN HEUSEN00:03:121939

-

12IN THE MOODGLENN MILLERJOE GARLAND00:03:371939

-

13I WANT TO BE HAPPYGLENN MILLERVINCENT YOUMANS00:03:071939

-

14INDIAN SUMMERGLENN MILLERV HERBERT00:03:181939

-

15FAREWELL BLUESGLENN MILLERE SCHOEBEL00:03:131939

-

16JOHNSON RAGGLENN MILLERG HALL00:02:501939

-

17STARDUSTGLENN MILLERH CARMICHAEL00:03:251940

-

18TUXEDO JUNCTIONGLENN MILLERW JOHNSON00:03:291940

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1WHEN JOHNNY COMES MARCHING HOMEGLENN MILLERP GILMORE00:03:111942

-

2PENNSYLVANIA 6 5000GLENN MILLERJ GRAY00:03:171940

-

3MR MEADOWLARKGLENN MILLERW DONALDSON00:02:281940

-

4FRESH AS A DAISYGLENN MILLERCOLE PORTER00:02:491940

-

5ALONG THE SANTA FE TRAILGLENN MILLERA L DUBIN00:03:221940

-

6YES MY DARLING DAUGHTERGLENN MILLERJ LAWRENCE00:02:301940

-

7IDA SWEET AS APPLE CIDERGLENN MILLERE LEONARD00:03:261941

-

8I DREAMT I DWELT IN HARLEMGLENN MILLERR WRIGHT00:03:421941

-

9SUN VALLEY JUMPGLENN MILLERJ GRAY00:03:011941

-

10THE SPIRIT IS WILLINGGLENN MILLERJ GRAY00:03:311941

-

11BOULDER BUFFGLENN MILLERE NOVELLO00:03:321941

-

12THE BOOGLIE WOOGLIE PIGGYGLENN MILLERR JACOBS00:03:231941

-

13TAKE THE A TRAINGLENN MILLERBILLY STRAYHORN00:03:281941

-

14A STRING OF PEARLSGLENN MILLERJ GRAY00:03:161941

-

15EVERYTHING I LOVEGLENN MILLERCOLE PORTER00:02:571941

-

16AMERICAN PATROLGLENN MILLERF W MEACHAM00:03:201942

-

17SWEET ELOISEGLENN MILLERM DAVID00:03:091942

-

18CARIBBEAN CLIPPERGLENN MILLERJ GRAY00:02:381942

GLENN MILLER SWING FOR VICTORY FA 192

GLENN MILLER

SWING FOR VICTORY

1937-1942

Glenn Miller

UN AMERICAIN VENDU*

1937-1942

La pire chose qui puisse arriver à un musicien de jazz au cours de sa carrière est de remporter beaucoup de succès; ce qui n’est pas le moindre des paradoxes dans ce monde-là. Voyez ce malheureux Dave Brubeck : acclamé par la critique au début des années cinquante, la couverture de Time Magazine en 1954, des victoires en série dans les référendums des revues Down Beat, Metronome et Play Boy. Ensuite, les choses se gâtèrent. Take Five, de Paul Desmond, l’un des titres de Time Out, l’album de Brubeck couronné de récompenses en 1959, fut commercialisé sous forme d’un 45 tours et devint un énorme tube des deux côtés de l’Atlantique. Du jour au lendemain, Dave fut jugé encombrant et se vit rejeté sans ménagement, soudain condamné par la critique à une espèce de Goulag auquel les artistes n’ayant pas reçu l’aval de la Nomenklatura devaient faire face à cette même époque en Union soviétique (où, très ironiquement, Brubeck s’attirait les faveurs du public et l’estime de la critique). Il se peut que les journalistes occidentaux n’aient pas souhaité ardemment que Dave en bave (un peu tout de même, oui) mais ce dont ils ne voulaient à aucun prix c’était entendre les routiers ou le petit personnel de chez Félix Potin siffloter ses airs. Tout en prodiguant leurs homélies qui fustigeaient les dérives commerciales, le fond de leur pensée était que Brubeck avait bel et bien trahi les siens, cette classe moyenne aisée qui envoie ses gosses à l’université, celle-là même dont il passait pour être le pur produit, du point de vue de la critique tout au moins.La réaction des critiques envers Glenn Miller est plus complexe encore, car, alors que la flexibilité de son orchestre lui valut de finalement rencontrer le succès à la fin des années trente, il s’était par avance prémuni contre ses éventuels détracteurs en faisant savoir que son ambition n’était pas de diriger un orchestre de jazz mais plutôt et avant tout - Enfer et damnation! - de faire de l’argent.

Peut-être n’était-ce pas précisément le genre de propos qu’il eût fallu tenir, étant donné que le jeune public de l’Ere du Swing comportait nombre d’idéalistes extatiques convaincus que la majorité des musiciens était prête à mourir de faim au nom de l’Art. Quoi qu’il en soit, le point de vue exprimé par Miller ne devait pas être, sur le fond, très éloigné de celui des autres chefs d’orchestre qui tenaient le haut du pavé à cette époque, Tommy Dorsey ou Benny Goodman, lesquels se montrèrent sans doute plus circonspects dans leurs déclarations publiques. A tous égards, Miller était quelqu’un de direct, qui possédait son franc-parler, et n’avait pas de temps à perdre avec les sots, les charlatans ou les rêveurs. Il ne consentait pas à rentrer dans le jeu des relations publiques tel que le monde du spectacle en avait fixé les règles habituelles et où le degré de volubilité d’un “artiste” est bien souvent inversement proportionnel à son talent réel. Comme tout musicien professionnel digne de ce nom, Miller se considérait d’abord et avant tout comme un artisan, se contentant de faire la démonstration tangible de son “art”, ou du contraire, face aux bavards patentés.Miller était né en 1904 à Clarinda, dans l’Iowa. De 1925 à 1928, il appartint à la formation de Ben Pollack, basée à Chicago, dans laquelle il côtoya cet autre futur grand leader de l’époque Swing, Benny Goodman. Le jeune Glenn était un tromboniste aussi consciencieux que compétent et d’une grande faculté d’adaptation ainsi qu’en témoignent ses divers enregistrements avec Pollack, sans compter de très nombreuses faces à la fin des années vingt, à la fois comme instrumentiste et arrangeur très prisé de gens aussi différents que le All Star Orchestra, les California Ramblers, Joe Candullo, les Charleston Chasers, 1es Cotton Pickers, les Louisiana Rhythm Kings, les Midnight Airedales, Irving Mills, les Mound City Blue Blowers, Red Nichols, Jack Pettis, Dick Robertson, Joe Venuti, les Whoopee Makers, les frères Dorsey, etc. Miller passa la seconde moitié de l’année 1934 comme membre à plein temps de la formation des Dorsey, jusqu’à ce que le chef d’orchestre anglais Ray Noble fasse appel à lui afin de mettre sur pied un ensemble américain dont le port d’attache serait le Rainbow Room à Manhattan à la fin de cette même année.

C’est en fournissant des arrangements à l’orchestre de Noble qu’il mit le doigt sur une sonorité d’anches appelée à devenir fameuse et qui résultait partiellement de la substitution d’une ligne de clarinette à celle du premier trompette, substitution rendue nécessaire par le fait qu’un nouveau trompettiste ne parvenait pas à exécuter certains détails des partitions écrites par Glenn dont l’étendue excédait son registre. Le son Glenn Miller découle de cette ligne jouée par une clarinette doublée une octave plus bas par le saxophone ténor.Miller monta son propre ensemble en 1937. Après un démarrage plutôt lent, la mayonnaise commença enfin à prendre en 1939. Toutefois, entre 1939 et 1942, son succès devait atteindre des proportions assez phénoménales : des émissions régulières à la radio, deux films à Hollywood, une série de tubes comprenant Moonlight Serenade, In The Mood, Tuxedo Junction et American Patrol. Glenn exigeait en outre une très grande discipline de la part de ses musiciens. L’idée de faire le boeuf toute la nuit sur St Louis Blues ne l’excitait pas vraiment. Il n’en fallait pas plus pour le discréditer aux yeux des puristes. Il va sans dire que l’on trouve encore des échos de cette attitude parmi les fans de jazz qui furent les témoins directs de l’ascension de Miller vers la célébrité. Si l’on jette un coup d’oeil à la discographie de Brian Rust (né en 1922) qui fait autorité en la matière, “Disques de jazz 1897-1942”, se glisse une remarque assez vacharde au motif douteux que “la majorité des faces Bluebird et Victor ne présentant que peu sinon aucun intérêt, seules celles antérieures à 1938 se trouvent ici répertoriées”. Le présent album s’occupant de la période 1937-1942 démontre à l’envi que pareille opinion est pour le moins sujette à discussion. Reste que Rust accorde un minimum d’attention à Miller alors que l’ouvrage de Jorgen Grunnet Jepsen, “Disques de Jazz 1942-1962”, l’ignore carrément, malgré les séances “civiles” effectuées pour le compte de la compagnie Victor et en dépit des nombreux et swingants V. Discs, sans parler des transcriptions radio de l’orchestre des Forces Expéditionnaires Alliées entre 1942 et 1944. Un pur déni d’existence! George Orwell, au secours!

Bien qu’étant crédité comme leader d’une formation de circonstance pour une séance Columbia en 1935, le premier enregistrement de Miller à la tête de sa propre formation eut lieu pour la marque Decca en mars 1937. Comme Glenn ne parvenait pas à trouver un batteur qui lui convenait, George Simon, journaliste à la revue Metronome, offrit ses services : “J’étais si nerveux que j’ai dû passer mon temps à aligner des triolets bancals”. Simon n’aurait pas dû s’inquiéter de la sorte car les résultats sur Peg O’ My Heart et Moonlight Bay sont tout à fait honorables. Néanmoins, l’avenir de Glenn après cette séance n’était pas encore franchement radieux. Malgré de nombreux engagements dans des hôtels à travers le pays (Nouvelle-Orléans, Dallas, Minneapolis), la formation ne possédait toujours pas de batteur correct. Plus inquiétant encore, le défilé des trompettistes portés sur la bouteille. Vers le début 1938, Miller en avait eu son soûl et mit fin à l’existence de l’orchestre. Sur quoi, trois mois plus tard, il faisait un nouvel essai avec quelques-uns des anciens membres auxquels se joignirent le clarinettiste Wilbur Schwarz - bientôt appelé à jouer un rôle décisif dans la section des anches - et un trompettiste de jazz épatant du nom de Johnny Austin, lequel amena avec lui un ami batteur nommé Bob Spangler. Au bout de deux mois, la formation commençait à bien sonner, comme l’on peut en juger sur le Dipper Mouth Blues de King Oliver et sur Sold American. Le second thème de ce dernier titre fait entendre une sorte de prototype du riff principal basé sur le blues qu’utilisera In The Mood. Ce morceau révèle aussi l’intérêt grandissant de Miller pour l’orchestre de Count Basie, ce qu’atteste la référence à peine voilée à One O’Clock Jump sur le troisième thème, avec sa basse ambulatoire jouant les quatre temps.Une autre recrue de choix durant cette période fut le ténor Tex Beneke, auquel incomberaient à l’avenir la plupart des solos de saxophone ainsi qu’une bonne partie des vocaux. Le pousseur de romances attitré était Ray Eberle, dont le frère Bob avait travaillé aux côtés de Miller dans l’orchestre des frères Dorsey. En fait, Ray n’avait jamais oeuvré de manière professionnelle auparavant, mais cela ne paraissait pas inquiéter Glenn qui chaperonna le chanteur jusqu’à ce qu’il se sente en confiance. Vraisemblablement, l’un des attraits supplémentaires d’Eberle tenait à son physique latin, ce qui n’était pas sans intérêt sur scène, ne fût-ce que pour détourner un instant l’attention des auditeurs lorsqu’il lui arrivait de vocaliser avec une justesse approximative.

En septembre 1938, Miller signa avec la compagnie RCA Victor. Sa première séance pour le label économique Bluebird donna King Porter Stomp, une version retouchée du fameux arrangement de Fletcher Henderson, sur l’introduction duquel Glenn livre un joli solo de trombone. La partie de saxophone alto est due à Bill Stegmeyer. A cette même époque, Miller est censé ne pas avoir eu les moyens de rémunérer un guitariste à plein temps et, de fait, les discographies n’en mentionnent aucun. Pourtant l’on entend bien une guitare rythmique sur King Porter Stomp, preuve que quelqu’un fut engagé pour en jouer à cette occasion.Malheureusement, les affaires de l’orchestre ne s’arrangeaient toujours pas. Glenn confia à George Simon : “Je me demande si ça ne serait pas aussi bien pour moi de tout laisser tomber, de reprendre le chemin des studios et de me contenter de jouer du trombone”. Curieusement, ce sont des sentiments identiques qu’exprime Guess I’ll Go Back Home, composition désenchantée de Willard Robison que l’orchestre enregistra quelque temps plus tard dans un arrangement accrocheur dû à Bill Challis, vétéran des années folles.L’éclatement redouté n’eut jamais lieu. Peu de temps après, alors que Miller était de retour en studio pour des répétitions (le 1er mars 1939, très précisément - jour de son 35e anniversaire), son impresario lui fit savoir que le Casino de Glen Island venait de programmer la formation pour l’été. Cette vaste salle de bal située à New Rochelle, dans le comté de Westchester, à quelques kilomètres au nord de New York, était un point de chute des plus importants pour les orchestres qui cherchaient à atteindre une audience nationale car elle faisait l’objet de nombreuses retransmissions radiophoniques en direct couvrant la totalité du territoire. La nouvelle de cet engagement se propagea rapidement et Miller fut aussitôt sollicité pour la période pré-estivale par le Meadowbrook à Cedar Grove, dans le New Jersey, autre salle de bal d’importance qui bénéficiait régulièrement d’émissions spéciales radiodiffusées. Le mois suivant, l’orchestre était de retour en studio pour y graver le célèbre thème de Miller, Moonlight Serenade, mettant en valeur la sonorité moelleuse caractéristique de la section d’anches que Glenn avait mise au point au cours des deux années précédentes.

Sur les morceaux plus rapides, des répétitions assidues avaient renforcé la cohésion d’ensemble de manière significative, ce qu’attestent Runnin’ Wild! - arrangé par Bill Finegan - et Sliphorn Jive, composition d’Eddie Durham destinée à faire briller le trombone.Bien que In The Mood soit probablement le succès le plus durable associé au nom de Miller, ce morceau n’était pourtant pas de sa main. On trouve déjà trace du riff principal sur un disque de Wingy Manone de 1930 ayant pour titre Tar Paper Stomp. Horace Henderson l’utilisa en 1931 comme second riff sur Hot And Anxious, enregistré par l’orchestre de son frère Fletcher ainsi que par Don Redman en 1932. La composition intitulée In The Mood est due à Joe Garland, saxophoniste et arrangeur avec la formation d’Edgar Hayes, laquelle comprenait une section de saxes à la sonorité épaisse très reconnaissable (essentiellement grâce au baryton de Garland) et une section rythmique pleine de ressort dont l’élément moteur était le jeune Kenny Clarke, bien avant que celui-ci n’invente le drumming bebop. En réalité, Garland avait déjà fait usage de ce riff sur un air composé par ses soins pour le Mills Blue Rhythm Band en 1935, There’s Rhythm In Harlem. Hayes grava la version princeps de In The Mood pour la firme Decca en février 1938, une bonne année et demie avant celle de Miller en août 1939. L’arrangement de Garland était clairement conçu pour “durer” lorsque l’orchestre jouait pour la danse, utilisant plusieurs riffs différents de manière répétitive. Toutefois, ramené aux limites d’un disque de trois minutes, le résultat obtenu fut plutôt aride. Bien que Miller ait utilisé la version intégrale lors de prestations plus anciennes saisies depuis le Casino de Glen Island, il simplifia le morceau pour le disque, supprimant plusieurs passages et se concentrant sur le caractère hypnotique des deux premiers riffs. Pour parer au risque de monotonie, un chase (1) entre les deux ténors Tex Beneke et Al Klink fut aménagé dans le but de faire baisser la tension. Pour une raison x, Glenn eut toujours un faible pour Beneke; celui-ci se voyant attribuer la plupart des solos de saxophone malgré un talent de jazzman plutôt modeste. Klink était probablement un meilleur improvisateur mais il n’eut pas souvent l’occasion d’en donner la preuve.

L’excitant diminuendo vers la fin du morceau et la montée chromatique conduisant au paroxysme final sont certainement l’oeuvre, respectivement, d’Eddie Durham et du pianiste Chummy Mc Gregor. Quoi qu’il en soit, ils concoctèrent ensemble un finale d’allure dramatique qui faisait justement défaut à l’orchestration première de Garland. Des émissions radio régulières depuis le Casino de Glen Island ouvrirent les portes d’un marché considérable au disque gravé en studio. Quant à Klink et Beneke, ils finirent par en avoir plus qu’assez de devoir sans cesse reproduire note pour note leur course-poursuite au ténor telle qu’elle avait été immortalisée dans la cire. Qu’advint-il du disque d’Edgar Hayes? A peu près rien.Grâce à l’impact de la radio, Miller battit des records d’affluence durant le reste de l’année dans tous les endroits où il lui arriva de se produire. Cela lui permit de récolter les fonds nécessaires pour apporter des améliorations sensibles à la composition de l’orchestre. Johnny Best prit place parmi les trompettes, et le magnifique joueur de baryton et clarinettiste texan Ernie Caceres rejoignit la troupe en février 1940. De plus en plus souvent, les arrangements furent confiés à Bill Finegan (voir Johnson Rag, Stardust, la relecture “Millerisée” du Rug Cutter’s Swing de Horace Henderson, etc.) ainsi qu’à un jeune transfuge de la formation d’Artie Shaw dissoute en 1939, Jerry Gray. Sans pouvoir se placer au même niveau de créativité que Finegan (lequel s’en fut après-guerre pour prendre la direction du célèbre orchestre Sauter-Finegan), Gray possédait pas mal de flair pour trouver des airs accrocheurs et sentait instinctivement ce qu’attendait Miller. Parmi ses contributions ayant le mieux résisté à l’usure du temps figurent Pennsylvania 6-5000 (coordonnées téléphoniques de l’hôtel Pennsylvania où la formation se produisait à Manhattan) et l’arrangement à succès de Tuxedo Junction, morceau composé par des membres de l’ensemble d’Erskine Hawkins, originaire de Birmingham, en Alabama. Ce titre mystérieux fait référence à l’endroit où se croisaient l’Avenue Ensley et la Vingtième Rue à Birmingham, là où se trouvait un terminus de tramway. Les cheminots et les ouvriers des aciéries avaient pour habitude de s’y arrêter après le travail, profitant d’un modeste établissement de bains-douches où ils pouvaient faire leur toilette et mettre des habits propres.

Ce qui leur permettait d’aller en ville sans avoir à repasser chez eux. Selon certaines sources, l’on y trouvait également un magasin de vêtements qui faisait l’angle et où l’on pouvait louer des habits de soirée (tuxedos (2)); les ouvriers laissant alors en gage leurs vêtements de travail.Au chapitre des doléances formulées à maintes reprises par Jerry Gray auprès de Miller figurait la lourdeur de la section rythmique. Cette situation devait changer définitivement en septembre 1940 avec l’arrivée de Herman Trigger Alpert qui occuperait également le poste de bassiste dans l’orchestre de l’Air Force au cours de la guerre. Sa deuxième apparition enregistrée avec Miller (le 8 novembre 1940) se trouve sur Fresh As A Daisy, nouveauté de Cole Porter d’une simplicité trompeuse arrangée par Gray. Le morceau déborde littéralement de vie grâce au soutien d’Alpert. Améliorée, la section rythmique se surpasse même la semaine suivante avec Yes, My Darling Daughter, une excitante partition de Gray. L’arrivée de Billy May, qui avait largement contribué à façonner le profil musical de la formation de Charlie Barnet, fut un plus important à la fois pour le pupitre des trompettes et pour l’équipe des arrangeurs. Miller était un grand admirateur de l’orchestre de Jimmie Lunceford, lequel tirait une bonne partie de son prestige au cours des années trente des arrangements de Sy Oliver. Sur Ida! Sweet As Apple Cider, May se réapproprie le style d’écriture décontracté qui était la signature d’Oliver aux plus beaux jours de l’orchestre Lunceford. Poussé par la contrebasse bondissante d’Alpert, ce morceau est notamment marqué par l’impeccable phrasé de la section d’anches.1941 vit se profiler la gloire promise quand l’orchestre prit le chemin de la Californie et de Hollywood. Après quelque six décennies de films avec orchestres, “Sun Valley Serenade” tient remarquablement la route. Le décor de la station de ski à la mode fournit à Jerry Gray l’occasion d’un jeu de mots sur le titre Sun Valley Jump. Les fans de Miller purent ainsi voir et entendre la formation dans maintes séquences tandis que les spectateurs moins friands de musique pouvaient toujours trouver leur bonheur en admirant les jambes de Sonja Henie, vedette du patinage.L’une des plus étonnantes “Millerisations” de cette époque fut l’arrangement de Billy May sur le Take The ’A’ Train de Billy Strayhorn. Cette gravure classique de Duke Ellington pour la marque Victor datait de février 1941, ce qui signifie que ce thème était encore tout neuf lorsque Miller s’avisa de l’enregistrer au mois de mai. A première vue, l’idée d’en faire une ballade paraît assez démente.

Cependant, à y regarder d’un peu plus près, l’on s’aperçoit que la ligne mélodique étirée en valeurs longues convient parfaitement à la conception de l’écriture que se faisait Miller pour ce type de morceaux. Après un premier chorus joué par l’habituelle section d’anches, un interlude orchestral introduit un solo de trompette bouchée magistralement délivré en contrepoint, tandis que les saxes suivent la mélodie. Avec sa pulsation balancée, aussi solide que feutrée, le morceau apparaît comme une réussite complète, et ce contre toute attente. A priori, cette interprétation de Take The ’A’ Train aurait pu souffrir de la comparaison avec l’original de Duke Ellington, qui renferme notamment un formidable solo du trompettiste Ray Nance. Or l’on s’aperçoit que Miller, malgré qu’il en ait, ne se sera pas toujours contenté de diriger un simple “orchestre de danse”, si remarquable ait-il pu être dans ce domaine, puisque derrière le professionnel acharné transparaît ici la figure plus complexe d’un homme qui ne devait pas être insensible à une certaine élégance de la forme. Ce dont le travail de Billy May porte ici témoignage, qui n’a trahi ni l’esprit de la composition originale de Strayhorn ni la personnalité de l’orchestre chargé de la réinterpréter. En tout cas, cette version de Take The ’A’ Train mérite d’être redécouverte sans préjugé aucun; sa musicalité ne justifiant nullement l’oubli relatif dans lequel elle est aujourd’hui tombée. Les amateurs de jazz seraient inspirés de s’en aviser. Près de soixante ans plus tard, il est non seulement impossible de demeurer insensible à cette interprétation mais il est en outre assez difficile de ne pas y voir un hommage rendu au génie de Billy Strayhorn, ce Duke Ellington en second.Comparativement, When Johnny Comes Marching Home, oeuvre du compositeur de ballades américano-irlandais Patrick Gilmore (1829-1892), est une chanson qui date de 1863, époque de la Guerre Civile; elle est ici transformée par Bill Finegan en un hymne martial moderne sur tempo rapide qui est à mille lieues de la métrique originelle en 6/8. Marion Hutton et les Modernaires se chargent de la revitalisante partie vocale et l’on y entend un solo de ténor particulièrement tonique, sans doute de Tex Beneke.

En dépit d’une apparente rigidité ignorant l’affectif dès qu’il s’agissait d’organisation, Miller savait faire preuve tout à la fois d’imagination et de générosité comme lorsqu’il fut question d’engager - décision inspirée - le cornettiste Bobby Hackett, dont le lyrisme bixien aurait pu sembler déplacé dans le cadre de la machine à swing dirigée par Miller. Ajoutons que de récents soins dentaires interdisaient formellement à Hackett de souffler dans son biniou. Nullement refroidi, Miller lui mit une guitare entre les mains, le temps que ses gencives aient cicatrisé, après quoi Bobby nous gratifia de quelques solos superbement mélodieux, comme sur A String Of Pearls ou, plus tard, Sweet Eloise.Après que l’attaque japonaise sur Pearl Harbor en décembre 1941 eut précipité les Etats-Unis dans le conflit mondial, Miller éprouva le sentiment qu’il pourrait se rendre utile à l’effort de guerre en rejoignant les forces armées. Ce pourquoi il mit un terme aux activités de son orchestre et s’engagea dans l’armée américaine. Habile en pourparlers, il s’arrangea pour négocier sa réputation dans le civil afin que lui soit attribué un rôle qui, concrètement, ferait de lui le musicien officiel de la Seconde Guerre mondiale - une distinction qu’au bout du compte il paierait de sa vie. Après avoir fait ses classes d’officier pendant deux mois, il obtint à titre temporaire le grade de capitaine, devenu effectif à partir du 7 octobre 1942. Au printemps 1943, il reçut l’autorisation de recruter, où qu’ils se trouvent basés, les premiers musiciens, jazzmen et autres, pour le nouvel orchestre qu’il était en train de mettre sur pied à New Heaven dans le Connecticut. Un an plus tard, l’orchestre de l’Air Force était devenu un ensemble superbement rôdé, capable de s’exprimer dans à peu près n’importe quel idiome, jazz, variété, voire gentiment symphonique.Au titre des préparatifs pour la libération de l’Europe occupée par les nazis, le commandement des Forces Alliées, basé en Grande-Bretagne, avait mis au point un programme radio à l’usage particulier des Forces Expéditionnaires Alliées, dont la diffusion démarra le matin suivant le débarquement en Normandie grâce à un puissant émetteur à ondes moyennes installé dans le sud du Devon. La fréquence était de 1050 kHz, ce qui signifiait qu’après la tombée de la nuit les programmes pouvaient être captés à travers l’Europe tout entière.

Dans la mesure où l’un des objectifs de la station était à la fois de fournir des nouvelles et le plus de divertissement possible en direct, la formation de Miller faisait figure de candidat idéal s’agissant de la partie musicale. L’orchestre de l’Air Force traversa donc l’Atlantique à la fin juin sur le paquebot recyclé “Queen Elizabeth” et fut sur les ondes le 9 juillet, annoncé comme l’“Orchestre des Forces Expéditionnaires Alliées”. L’impact de cette formation, en tant que soutien moral des Alliés mais aussi comme outil de propagande, ne peut être sous-estimé. On pourrait certes dire qu’en un sens Miller a été l’arme la plus efficace et la moins secrète des Alliés pendant la dernière année de la guerre. Question armes cependant, peu de Londoniens oublieraient les V-1 tombés du ciel et personne ne contesterait non plus que les sous-marins allemands furent le fléau de l’Atlantique. Quoi qu’il en soit, durant la seconde moitié de 1944, Glenn Miller se trouvait littéralement partout sur le théâtre des opérations en Europe, avec ses émissions radio qui frappaient loin derrière les lignes ennemies.A l’automne 1944, un jeune ingénieur du son germanique affecté sur le front russe, Gerhard Lehner, prit livraison de matériel destiné à équiper la station radio locale des forces de la Wehrmacht. Il s’agissait en l’occurrence de magnétophones fabriqués par le constructeur Lorenz, capables d’enregistrer et de restituer discours et musique avec une fidélité sonore qui était à l’époque inconnue aux Etats-Unis. L’usage supposé de cet appareil était d’enregistrer à l’attention des troupes allemandes des programmes d’actualités et des discours de propagande du Dr Goebbels et du Führer. Néanmoins, les services de l’Intendance avaient eu l’excellente idée de rajouter à cet envoi quelques échantillons supplémentaires de bande Agfa. De service cette nuit-là, et bien d’autres par la suite, Gerhrard brancha l’appareil sur les fréquences radio et sonda l’éther en quête de sonorités susceptibles de rendre un sens à l’existence. Au risque de se voir traduit en cour martiale et de se retrouver face à un peloton d’exécution, il réalisa ainsi ce qui furent probablement les premiers et uniques enregistrements radio sur BANDE de l’orchestre de l’Air Force dirigé depuis Londres par le récemment promu major Glenn Miller. Douze ans après la disparition de Glenn Miller à bord d’un petit avion au-dessus de la Manche, Gerhard Lehner devint ingénieur du son chez Barclay, le label jazz français numéro un. Quoi que pourraient en penser les ayatollahs du jazz, Glenn Miller en est, au moins partiellement, responsable, de manière posthume il est vrai. Incidemment, les bandes se trouvent toujours entre les mains de Gerhard...

Tony BALDWIN

(traduit de l’anglais par Alain Pailler)

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS/ GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 2000.

NOTES

(*) Il s’agit de la traduction littérale d’un titre figurant au répertoire de l’orchestre de Glenn Miller, Sold American. A la lecture des premiers paragraphes de ce texte, le lecteur comprendra mieux le sens de cette épithète, utilisée ici avec ironie par l’auteur en réponse aux puristes, pour ne pas dire aux intégristes du jazz (côté critiques/amateurs), encore trop souvent prisonniers d’une aveuglante mythologie de l’artiste-martyr. N.d.t.

(1) “Chase (littéralement : chasse, poursuite). Par ce terme on désigne une joute opposant/réunissant deux ou plusieurs instrumentistes, souvent de même nature, qui, à tour de rôle, improvisent sur un nombre de mesures donné, généralement quatre mesures chacun...”. André Clergeat et Philippe Baudoin, Dictionnaire du jazz (Ed. R. Laffont, coll. “Bouquins”, p. 187 - 1988).

(2) Tuxedo, en anglais, désigne cet habit qu’en français (si l’on peut dire) l’on appelle smoking.

Glenn Miller

Sold American

1937-1942

One of the great paradoxes of the jazz world is that the worst possible career move you can ever make is to become a major success. Consider the wretched Dave Brubeck: critical acclaim throughout the early 1950s, the cover of Time Magazine in 1954 and successive Down Beat, Metronome and Playboy poll wins. But then things got out of hand. Paul Desmond’s Take Five, one of the tracks from from Brubeck’s award-winning 1959 album ‘Time Out’, was released as a 45 r.p.m. single and became a huge pop hit on both sides of the Atlantic. Suddenly Dave was an embarassment. He found himself summarily banished to a critical wilderness as bleak as anything that ‘unapproved’ artists had to face in the Soviet Union (where, ironically, he maintained both popularity AND critical status). Jazz journalists in the West may not have actively wished Dave to suffer for his art (well, only a bit), but they certainly did not want to hear truckers or check-out staff at K-Mart whistling his tunes. While mouthing homilies about commercialism, the pundits were really saying that Brubeck had betrayed the cosy middle-class college crowd that, in critical terms at least, was seen to have spawned him.The critical reaction to Glenn Miller is more complex, as, when the versatility of his orchestra eventually brought success his way at the end of the 1930s, he made a pre-emptive strike against potential detractors by saying that he had no ambition to lead a jazz band and that – shock, horror! – he was mainly interested in making money. Perhaps it was not the most tactful announcement that he could have made, given that the young Swing public was full of wide-eyed idealists, convinced that most musicians would prefer to starve for their art. However, Miller’s views cannot have been significantly different from those of other successful contemporary bandleaders, like Tommy Dorsey and Benny Goodman, who were perhaps more guarded in their public statements.

By all accounts Miller was a straightforward, somewhat blunt personality who had little time for fools, charlatans or dreamers. He refused to play the public-relations game according to the usual show-business rules, where the degree of effusiveness of an ‘artist’ is frequently in the inverse proportion to his talent. Like any professional musician worth his salt, Miller considered himself first and foremost a craftsman, and was content to leave weighty assessments of his ‘artistry’, or lack of it, to the chattering classes. Miller was born in Clarinda, Iowa, in 1904. From 1925 to 1928 he was a member of the Chicago-based Ben Pollack orchestra, together with that other great future Swing leader, Benny Goodman. Young Glenn was a thoroughly competent all-round trombonist, as demonstrated by his various records with Pollack, plus countless late-1920s sides as a jobbing musician and arranger with the All-Star Orchestra, the California Ramblers, Joe Candullo, the Charleston Chasers, the Cotton Pickers, the Louisiana Rhythm Kings, the Midnight Airedales, Irving Mills, the Mound City Blue Blowers, Red Nichols, Jack Pettis, Dick Robertson, Joe Venuti, the Whoopee Makers and the Dorsey Brothers, etc., etc. Miller spent the latter part of 1934 as full-time member of the Dorseys’ band, until the English bandleader Ray Noble hired him to put together an American orchestra for a residency at Manhattan’s Rainbow Room at the end of that year. It was while arranging for Noble’s band that he came upon his famous reed sound, which was partly the result of having had to substitute a clarinet for the lead trumpet, when a replacement musician could not handle the range of some of Glenn’s charts. The Miller sound derived from that clarinet lead line being doubled an octave lower by a tenor saxophone.Miller formed his own outfit in 1937. After a fairly slow start, business finally began to pick up in 1939. However, between 1939 and 1942 his success achieved truly phenomenal proportions, with regular broadcasts, two Hollywood films and a string of record hits that included Moonlight Serenade, In The Mood, Tuxedo Junction and American Patrol. Glenn also insisted on a very high standard of disciplined musicianship. The idea of jamming on the St. Louis Blues all night did not really appeal to him.

That alone was more than enough to damn him in the eyes of jazz purists. Indeed, one still finds echoes of this attitude among the generation of jazz fans that witnessed the Miller band’s rise to fame at first hand. If one looks up Miller in Brian Rust’s (b.1922) authoritative discography, “Jazz Records 1897-1942”1, there is a slightly grudging note to the effect that “as the majority of the Bluebird and Victor sides are of little or no jazz interest, only those made prior to 1938 are listed here.” Dealing, as it does, with the 1937-1942 period, the present album amply demonstrates that this view is somewhat questionable. Still, at least Rust gives Miller a mention, whereas in Jorgen Grunnet Jepsen’s “Jazz Records 1942-1962”, despite the civilian Victor sessions and the many swinging V-Discs and radio transcriptions by the AAF band between 1942 and 1944, Glenn Miller does not even exist. Literally, a non-person! – George Orwell, where are you? While he gets credit as leader on a 1935 pick-up session for Columbia, Miller’s first record date with his own working band was for Decca in March 1937. As Glenn could not find a drummer he liked, Metronome journalist George Simon stood in: “I was so nervous that I must have been playing uncontrolled triplets throughout.” Simon need not have worried, as the results on Peg O’ My Heart and Moonlight Bay, both Miller arrangements, are perfectly acceptable. However, for Glenn it was far from plain sailing after that. Despite a number of hotel bookings around the country (New Orleans, Dallas, Minneapolis), the band still did not have a decent drummer. More worrying was the fact that successive trumpet players were inveterate drunks. By early 1938 Miller had had enough, and he actually broke up the band. Still, three months later he had another try with a few of the old members, plus clarinetist Wilbur Schwartz – soon to play the distinctive lead voice in Miller’s reed choir – and an exciting jazz trumpet player called Johnny Austin, who brought in a drummer friend called Bob Spangler. After a couple of months the band was beginning to sound confident, as heard on King Oliver’s Dipper Mouth Blues and Sold American.

The latter contains a second strain that is a kind of prototype for the main blues riff of In the Mood. The piece also reveals Miller’s increasing interest in the Count Basie orchestra, as demonstrated by the thinly veiled quote from One O’Clock Jump in the third strain, with its four-beat walking bass. Another new asset at this period was tenor player Tex Beneke, who would take most future sax solos and also handle a fair proportion of the vocals. The band’s romantic singer was Ray Eberle, whose brother Bob had worked alongside Miller in the Dorsey Brothers’ band. In fact Ray had never worked professionally before, but that did not seem to worry Glenn, who coached the singer until he felt he was up to standard. Presumably Eberle’s other attraction was his Latin looks, which must have worked well on the stand, at least to the extent of deflecting attention from his occasionally uncertain pitch. In September 1938 Miller signed with RCA Victor. His first session for their 35-cent Bluebird label produced King Porter Stomp, a modified version of Fletcher Henderson’s famous arrangement, which Glenn opens with a fine trombone solo. Bill Stegmeyer plays solo alto, which sounds uncannily like a soprano. At this period Miller is supposed not to have been able to afford a full-time guitarist, and, indeed, the discographies do not list one. However, a rhythm guitar is clearly audible on King Porter, so someone was evidently hired for the occasion. Unfortunately, things kept on going wrong with the band. Glenn confided to George Simon, “I guess I may as well give it all up and go back in the studios and just play trombone.”2 Interestingly, these are precisely the feelings expressed in a wistful Willard Robison song that the band recorded later that year, Guess I’ll Go Back Home, which benefits from an attractive arrangement by the 1920s veteran, Bill Challis.The threatened break-up never happened. A short time afterwards, when Miller was back in the rehearsal studios (to be precise, 1st March 1939 – his thirty-fifth birthday), his agent called to say that the Glen Island Casino had booked the band for the summer. This large ballroom in New Rochelle, Westchester County, a few miles north of New York City, was a crucially important venue for bands seeking national exposure, as it was the source of many NBC coast-to-coast live radio broadcasts. Word of the engagement soon got around and Miller was immediately hired for the pre-summer period by the Meadowbrook in Cedar Grove, New Jersey, another large ballroom with regular radio hook-ups.

The following month the band was back in the studio to record Miller’s famous theme song, Moonlight Serenade, which featured the characteristically smooth reed sound that Glenn had developed over the previous couple of years. On faster numbers assiduous rehearsal had produced a truly tight ensemble, as can be heard on Runnin’ Wild! – arranged by Bill Finegan – and the trombone feature Sliphorn Jive, an Eddie Durham original. While In The Mood is probably Miller’s most lasting hit, the tune was not his. The principal riff can be traced back to a 1930 Wingy Manone record called Tar Paper Stomp. Horace Henderson used it in 1931 as the second riff in Hot And Anxious, as recorded by his brother Fletcher Henderson’s band and, in 1932, by Don Redman. In The Mood itself was written by Joe Garland, saxophonist and arranger with the Edgar Hayes band, which had a distinctively fat sax sound (thanks mainly to Garland’s baritone) and a driving rhythm section propelled by the young Kenny Clarke, many years before he invented bebop drumming. Actually, Garland had already used this riff in a tune that he had written for the Mills Blue Rhythm band in 1935, There’s Rhythm In Harlem. Hayes recorded the original In The Mood for Decca in February 1938, a full eighteen months before Miller’s August 1939 version. Garland’s arrangement was clearly designed for extended dance-hall performance, being made up of a number of different repeated riffs. However, compressed into the confines of a three-minute record, this produced a rather dessicated result. Although Miller had used the full version on early broadcasts from the Glen Island Casino, for the recording he simplified the piece, cutting out several passages and concentrating on the hypnotic first two riffs. Just when this might seem in danger of getting monotonous, the tension is broken by the two-tenor chase between Tex Beneke and Al Klink. For some reason Glenn always took a particular shine to Beneke, who, despite a fairly modest jazz talent, was given most of the available tenor solos. Klink was probably the better improvisor, but did not often get the chance to prove it. The teasing diminuendo towards the end of the number and the chromatic build-up to its ultimate climax are probably the work of Eddie Durham and pianist Chummy McGregor, respectively. Anyway, together they produced a dramatic finale, which was one thing that Joe Garland’s original orchestration lacked.

Regular airing from the Glen Island Casino generated an immense market for the subsequent record release, Bluebird 10416, and in time Klink and Beneke became thoroughly fed up with being expected to reproduce their recorded tenor chase, note for note. Whatever happened to the Edgar Hayes record? Essentially, nothing. Thanks to the impact of radio, for the rest of the year Miller broke attendance records wherever he played. This gave him the funds to make significant improvements to the band. Johnny Best came in on trumpet, and the splendid Texan clarinet and baritone player Ernie Caceres joined in February 1940. Arrangements were increasingly delegated to Bill Finegan (e.g. Johnson Rag; Stardust, the ‘Millerised’ rewrite of Horace Henderson’s Rug Cutter’s Swing, etc.) and to a young refugee from the 1939 collapse of Artie Shaw’s band, Jerry Gray. While not having the same creative originality as Finegan (who went on to run the famous Sauter-Finegan orchestra with Eddie Sauter after the war), Gray had a gift for catchy ideas and a precise feel for what Miller wanted. Among his most enduring contributions are Pennsylvania 6-5000 (the telephone number of Manhattan’s Pennsylvania Hotel, where the band played) and the hit arrangement of Tuxedo Junction, a piece written by members of the Erskine Hawkins band from Birmingham, Alabama. The mysterious title refers to the intersection of Ensley Avenue and 20th Street, Birmingham, where there used to be a streetcar terminus. Workers from the railroads and steel mills used to stop at the small wash-house there after work, to clean up and change into their suits. This meant that they could go out on the town without first having to return home. According to some sources there was also a clothing store on the corner that would rent out dinner suits (Tuxedos) to workers, who would then leave their working clothes as security.One of Jerry Gray’s frequent complaints to Miller was about the stodginess of the band’s rhythm section. In September 1940 this was to change forever with the arrival of Herman Trigger Alpert, who was also to occupy the bass stool in the Army Air Forces band throughout the war. His first recorded appearance with Miller (8 November 1940) was on Gray’s arrangement of Fresh As A Daisy, a deceptively simple Cole Porter novelty. With Alpert driving the band, the number positively soars into life. The improved rhythm section excelled itself the following week in Gray’s exciting chart of Yes, My Darling Daughter.

Another important addition to both the trumpet section and the arranging roster came with the arrival of Billy May, who had done much to mould the musical personality of the Charlie Barnet band. Miller was a great admirer of the Jimmie Lunceford orchestra, which owed much of its stylistic panache in the 1930s to the arrangements of Sy Oliver. On Ida! Sweet As Apple Cider May perfectly captures Oliver’s relaxed writing for the Lunceford band in its heyday. The side includes some immaculate reed-section phrasing, offset by Alpert’s loping bass.1941 saw the Glenn Miller orchestra on its way to California and the promise of Hollywood stardom. As band movies go, after nearly sixty years “Sun Valley Serenade” stands up remarkably well. The fashionable ski-resort setting gave Jerry Gray an excuse for his punning title, Sun Valley Jump. The film provided Miller fans with plenty of opportunities to see and hear the band, while the less musically-inclined could always admire skating-star Sonja Henjie’s legs. One of the more astonishing ‘Millerisations’ of this period was Billy May’s arrangement of Billy Strayhorn’s Take The ‘A’ Train. Duke Ellington had made his classic Victor recording of the piece in February 1941, so when Miller came to record it in May the tune was still fairly new. At first sight, the idea of turning it into a ballad seems insane. However, closer examination reveals that the long-held notes of the melody fit perfectly into Miller’s conception of ballad writing. After an initial chorus from the reed section, a band interlude leads into a masterful, muted contrapuntal trumpet solo, while the saxes keep to the melody. With its gentle, yet rock-solid swing, the piece is a definite, if wholly unexpected, triumph.Another remarkable Miller adaptation drew from a completely different source. When Johnny Comes Marching Home is an 1863 Civil War song by the Irish-American balladeer Patrick Gilmore (1829-1892), transformed by Bill Finegan from its original 6/8 metre to an up-tempo modern battle anthem. Marion Hutton and the Modernaires provide the uplifting vocal, and there is an impressively trenchant tenor solo, presumably from Al Klink.For someone with rigidly dispassionate views about discipline and organization, Miller was capable of both considerable imagination and personal generosity, as in the case of his inspired decision to hire cornetist Bobby Hackett, whose Bixian lyricism might have seemed out of place in the Miller Swing machine.

To complicate matters, recent dental work prevented Hackett from blowing his horn with any power. Undaunted, Miller put him on guitar until his gums had healed, and thereafter Bobby contributed some wonderfully melodic solos, as on A String Of Pearls and, later, Sweet Eloise. After Japan’s December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbour had brought the U.S.A. into the global conflict, Miller felt he could make a useful contribution to the war effort as a member of the armed forces. He duly broke up his band and volunteered for the United States Army. A skilled negotiator, he managed to parlay his civilian fame into a role that, in practical terms, would make his music the official sound of World War Two – a distinction that he ultimately paid for with his life. After a couple of months of basic officer training, Captain Miller emerged with a temporary wartime commission, effective from 7 October 1942. By the spring of 1943 he had the authority to recruit former professional dance and jazz musicians, wherever they were stationed, for a new orchestra that he was forming in New Heaven, Connecticut. A year later the Army Air Forces Band had become a superbly well-drilled outfit that was capable of playing virtually any sort of jazz, popular or light classical idiom. As part of the preparations for the D-Day invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe in June 1944, the British-based allied command had organized a special radio service for the Allied Expeditionary Forces, which began broadcasting to the continent the morning after the Normandy landings from a powerful medium-wave transmitter in South Devon. With a frequency of 1050 kHz, the station could be picked up throughout Europe after dark. Besides news, the station aimed to broadcast as much live entertainment as possible, and Miller’s outfit was considered to be an ideal candidate to provide the music. The Army Air Forces Band crossed the Atlantic on the converted liner “Queen Elizabeth” at the end of June. It was on the air by 9th July, and later billed as the “Band of the AEF”. The extent of the orchestra’s usefulness, both as an Allied morale-booster and as a propaganda tool, cannot be underestimated. Indeed, in one sense Miller could be said to have been the Allies’ least secret but most effective weapon of the final year of the war. In terms of weaponry, few Londoners would forget the V-1 flying bombs and no-one would dispute that German U-Boats were the scourge of the Atlantic.

However, in the second half of 1944 Glenn Miller was literally everywhere in the European theatre of war, with his broadcasts to German forces striking deep behind enemy lines. In the autumn of 1944, Gerhard Lehner, a young German signals engineer on the Russian Front, took delivery of some new studio equipment for the Wehrmacht’s local ‘Soldatensender’ radio station. This turned out to be one of the new Lorenz tape machines, which could record and reproduce speech and music with a fidelity that was unknown in the U.S. at the time. The machine was supposed to be used for recording news and propaganda speeches by Dr. Goebbels and the Führer for later replay to the German troops. However, the quartermaster had thoughtfully provided plenty of extra reels of Agfa tape. On duty that night, and for many nights afterwards, Gerhard hooked up the machine to the station’s sensitive communications receiver and trawled the ether for some sounds that might make life more interesting. At the risk of facing a court martial and the firing squad, he made what were probably the first and only off-air TAPE recordings of the recently-promoted Major Glenn Miller’s Army Air Forces Band broadcasts from London. In 1956, twelve years after Miller’s disappearance in a light aircraft over the English Channel, Gerhard Lehner became chief engineer of Barclay, France’s leading independent label. Whatever the jazz ayatollahs might say, at least some of the credit for this should go to Major Miller, albeit posthumously. And, incidentally, Gerhard still has the tapes...

Tony Baldwin

NOTES

(1) London, Storyville Publications (1970).

(2) G.T. Simon, The Big Bands, New York, Schirmer Books, 1967.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS/ GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 2000.

DISCOGRAPHIE

CD1

1. RUG CUTTER’S SWING. Glenn Miller (tb, dir); Clyde Hurley, Legh Knowles, Dale McMickle, Johnny Best (tp); Howard Gibeling, Paul Tanner, Frank D’Annolfo (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Hal McIntyre (as); Jimmy Abato (as, bar); Tex Beneke, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Richard Fisher (g); Rowland Bundock (b); Maurice Purtill (dm); Bill Finegan (arr). New York, 29 janvier 1940. BLUEBIRD B10754 (mx. 046738-1)

2. PEG O’ MY HEART. Glenn Miller (dir, tb, arr); Charlie Spivak, Manny Klein, Sterling Bose (tp); Jesse Ralph, Harry Rodgers (tb); George Siravo, Hal McIntyre (cl, as); Jerry Jerome, Carl Biesacker (cl, ts); Howard Smith (p); Dick McDonough (g); Ted Kotsoftis (sb); George Simon (dm ). New York, 22 mars 1937. DECCA 1342 (mx. 62058-A)

3. MOONLIGHT BAY. Même formation et même séance que pour Peg O’ My Heart.. Orchestre (voc). DECCA 1239 (mx. 62062-A).

4. DIPPER MOUTH BLUES. Glenn Miller (dir, tb, arr); Pee Wee Irwin, Bob Price, Ardell Garrett (tp); Jesse Ralph, Bud Smith (tb); Irving Fazola (cl); Hal McIntyre, Tony Viola (as); Jerry Jerome, Carl Biesacker (ts); J.C. “Chummy” McGregor (p); Carmen Maestren (g); Rowland Bundock (b); Doc Carney (dm). New York, 23 mai 1938. BRUNSWICK 8173 (mx. 22975-1).

5. SOLD AMERICAN. Même formation et même séance que pour Dipper Mouth Blues. Orchestre (voc). BRUNSWICK 8I73 (mx. 22974-1).

6. KING PORTER STOMP. Glenn Miller (dir, tb, arr); Johnny Austin, Louis Mucci, Bob Price (tp); Al Mastren, Paul Tanner (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as);Hal McIntyre (as); Bill Stegmeyer (ts, as); Tex Beneke (ts); Stanley Aronson (as, bar); inconnu (g); Chummy McGregor (p); Rowland Bundock (b); Bob Spangler (dm). New York, 27 septembre 1938. BLUEBIRD B7853 (mx. 027413).

7. MOONLIGHT SERENADE. Glenn Miller (dir, tb, arr); Bob Price, Legh Knowles, Dale McMickle (tp); Al Mastren, Paul Tanner (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Hal McIntyre (as); Stanley Aronson (as, bar); Tex Beneke, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Allen Reuss (g); Rowland Bundock (b); Frank Carlson (dm). New York, 4 avril 1939. BLUEBIRD B10214 (mx. 035701-1).

8. RUNNIN’ WILD! Glenn Miller (dir, tb); Bob Price, Legh Knowles, Dale McMickle (tp); Al Mastren, Paul Tanner (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Hal McIntyre (as); Stanley Aronson (as, bar); Tex Beneke, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Arthur Ens (g); Rowland Bundock (b); Maurice Purtill (dm). Bill Finegan (arr). New York, 18 avril 1939. BLUEBIRD B10269 (mx. 035767-2).

9. GUESS I’LL GO BACK HOME. Glenn Miller (dir, tb); Clyde Hurley, Legh Knowles, Dale McMickle (tp); Al Mastren, Paul Tanner (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Hal McIntyre (as); Gabriel Gelinas (as, bar); Tex Beneke (ts, voc); Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Arthur Ens (g); Rowland Bundock (b); Maurice Purtill (dm). Bill Challis (arr). New York, 18 avril 1939. BLUEBIRD B10317 (mx. 037179-1).

10. SLIP HORN JIVE. Même formation et même séance que pour Guess I’ll Go Back Home. Eddie Durham (arr). BLUEBIRD B10317 (mx. 037182-4).

11. BLUE RAIN. Glenn Miller (dir, tb, arr); Clyde Hurley, Legh Knowles, Dale McMickle (tp); Al Mastren, Paul Tanner, Toby Tyler (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Hal McIntyre (as); Jimmy Abato (as, bar); Tex Beneke, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Arthur Ens (g); Rowland Bundock (b); Maurice Purtill (dm). Ray Eberle (voc). New York, 3 octobre 1939. BLUEBIRD B10486 (mx. 042780-1).

12. IN THE MOOD. Glenn Miller (dir, tb,arr); Clyde Hurley, Legh Knowles, Dale McMickle (tp); Al Mastren, Paul Tanner (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Hal McIntyre (as); Harold Tennyson (as, bar); Tex Beneke, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Richard Fisher (g); Rowland Bundock (b); Maurice Purtill (dm). New York, 1 août 1939. BLUEBIRD B10416 (mx. 038170-1).

13. I WANT TO BE HAPPY. Même formation et même séance que pour In the Mood. Eddie Durham (arr). BLUEBIRD B10416 (mx. 038174-1).

14. INDIAN SUMMER. Même formation que pour Blue Rain. Ray Eberle (voc). New York, 5 novembre 1939. BLUEBIRD B10495 (mx. 043354-1).

15. FAREWELL BLUES. Même formation et même séance que pour In the Mood. Eddie Durham (arr).BLUEBIRD B10495 (mx.038175-1).

16. JOHNSON RAG. Même formation que pour Blue Rain. New York, 5 novembre 1939. Bill Finegan (arr). BLUEBIRD B10498 (mx. 043356-2).

17. STARDUST. Même formation et même séance que pour Rug Cutter’s Swing. Bill Finegan/Glenn Miller (arr). BLUEBIRD B10665 (mx. 046735-1).

18. TUXEDO JUNCTION. Glenn Miller (tb, dir); Clyde Hurley, Legh Knowles, Dale McMickle, Johnny Best (tp); Tommy Mack, Paul Tanner, Frank D’Annolfo (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Hal McIntyre (as); Jimmy Abato (as, bar); Tex Beneke, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Richard Fisher (g); Rowland Bundock (b); Maurice Purtill (dm); Jerry Gray (arr). New York, 29 janvier 1940. BLUEBIRD B10612 (mx. 046786-2).

CD2

1. WHEN JOHNNY COMES MARCHING HOME. Glenn Miller (tb, dir); Dale McMickle, Johnny Best, Billy May, Steve Lipkins (tp); Jimmy Priddy, Paul Tanner, Frank D’Annolfo (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Lloyd “Skippy” Martin (as); Ernie Caceres (as, bar); Tex Beneke, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Bobby Hackett (g); Edward “Doc” Goldberg (b); Maurice Purtill (dm); Marion Hutton, The Modernaires [Chuck Goldstein, Bill Conway, Hal Dickenson, Ralph Brewster] (voc); Conway, Dickenson (arr voc); Bill Finegan (arr). New York, 17 février 1942. BLUEBIRD B11480 (mx. 071864-1).

2. PENNSYLVANIA 6-5000. Glenn Miller (tb, dir); Legh Knowles, Charles Frankenhouser, Zeke Zarchey, Clyde Hurley, Johnny Best, Billy May (tp); Jimmy Priddy, Paul Tanner, Frank D’Annolfo (tb); Hal McIntyre, Wilbur Schwartz, Jimmy D’Abato (as); Lloyd “Skippy” Martin (as); Ernie Caceres (as, bar); Tex Beneke, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Jack Lathrop (g); Roland Bundock (b); Maurice Purtill (dm); orchestre (voc); Jerry Gray (arr). New York, 28 avril 1940. BLUEBIRD B10754 (mx. 048963-1).

3. MR. MEADOWLARK. Même formation et même séance que pour Pennsylvania 6-5000 . Jack Lathrop (voc). BLUEBIRD B10745 (mx. 048967-1).

4. FRESH AS A DAISY. Glenn Miller (tb, dir); Dale McMickle, Johnny Best, Billy May, Ray Anthony (tp); Jimmy Priddy, Paul Tanner, Frank D’Annolfo (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Hal McIntyre (as); Ernie Caceres (as, bar,cl); Tex Beneke (ts, voc); Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Jack Lathrop (g, voc); Herman “Trigger” Alpert (b); Maurice Purtill (dm); Marion Hutton (voc); Jerry Gray (arr). New York, 8 novembre 1940. BLUEBIRD B10959 (mx. 057610-1).

5. ALONG THE SANTA FE TRAIL. Même formation et même séance que pour Fresh As A Daisy. Ray Eberle (voc). BLUEBIRD B10970 (mx.057612-1).

6. YES, MY DARLING DAUGHTER. Même formation que pour Fresh As A Daisy. Marion Hutton, orchestre (voc); Jerry Gray (arr). New York, 14 novembre 1940. BLUEBIRD B10970 (mx. 057949-1).

7. IDA! SWEET AS APPLE CIDER. Même formation que pour Fresh As A Daisy. Tex Beneke (voc); Billy May (arr). New York, 17 janvier 1941. BLUEBIRD B11079 (mx. 058884-2).

8. I DREAMT I DWELT IN HARLEM. Même formation que pour Fresh As A Daisy. New York, 17 janvier 1941. Jerry Gray (arr). BLUEBIRD B11063 (mx. 058888-1).

9. SUN VALLEY JUMP. Même formation que pour Fresh As A Daisy. Jerry Gray (arr). New York, 22 janvier 1941. BLUEBIRD B11110 (mx. 058889-1).

10. THE SPIRIT IS WILLING. Même formation que pour Fresh As A Daisy. Jerry Gray (arr). New York, 19 février 1941. BLUEBIRD B11135 (mx. 060912-1).

11. BOULDER BUFF. Glenn Miller (tb, dir); Ralph Brewster, Mickey McMickle, Johnny Best, Billy May, Ray Anthony (tp); Jimmy Priddy, Paul Tanner, Frank D’Annolfo (tb); Wilbur Schwartz, Hal McIntyre, Ernie Caceres, Tex Beneke, Al Klink (saxes); Chummy McGregor (p); Jack Lathrop (g); Herman “Trigger” Alpert (b); Maurice Purtill (dm); Fred Norman (arr). Hollywood, 7 mai 1941. BLUEBIRD B11163 (mx. 061243-1).

12. THE BOOGLIE WOOGLIE PIGGY. Même formation et même séance que pour Boulder Buff. Tex Beneke, Paula Kelly, The Modernaires (voc); Jerry Gray (arr). BLUEBIRD B11163 (mx. 061244-1).

13. TAKE THE ‘A’ TRAIN. Glenn Miller (tb, dir); Dale McMickle, Johnny Best, Billy May, Ray Anthony (tp); Jimmy Priddy, Paul Tanner, Frank D’Annolfo (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Hal McIntyre (as); Ernie Caceres (as, bar,cl); Tex Beneke, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Bill Conway (g); Herman “Trigger” Alpert (b); Maurice Purtill (dm); Billy May (arr). Hollywood, 28 mai 1941. BLUEBIRD B11187 (mx. 061266-1).

14. A STRING OF PEARLS. Glenn Miller (tb, dir); Dale McMickle, Johnny Best, Billy May, Alec Fina (tp); Jimmy Priddy, Paul Tanner, Frank D’Annolfo (tb); Wilbur Schwartz (cl,as); Benjamin Feman (as); Ernie Caceres (as, bar,cl); Irving “Babe” Russin, Al Klink (ts); Chummy McGregor (p); Bobby Hackett (g, cnt); Edward “Doc” Goldberg (b); Maurice Purtill (dm); Jerry Gray (arr). New York, 3 novembre 1941. BLUEBIRD B11382 (mx. 068068-1).

15. EVERYTHING I LOVE. Même formation et même séance que pour A String Of Pearls. Ray Eberle, orchestre (voc); Jerry Gray (arr). BLUEBIRD B11365 (mx. 068067-1).

16. AMERICAN PATROL. Même formation que pour When Johnny Comes Marching Home. Hollywood, 2 avril 1942. VICTOR 27873 (mx. 072230-1).

17. SWEET ELOISE. Même formation et même séance que pour When Johnny Comes Marching Home, plus Bobby Hackett (cnt); Ray Eberle, The Modernaires (voc); Jerry Gray (arr).

18. CARIBBEAN CLIPPER. Même formation que pour When Johnny Comes Marching Home. Jerry Gray (arr). Chicago, 30 juin 1942. VICTOR 20-1536 (mx. 074738-1).

CD Glenn Miller © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)