- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

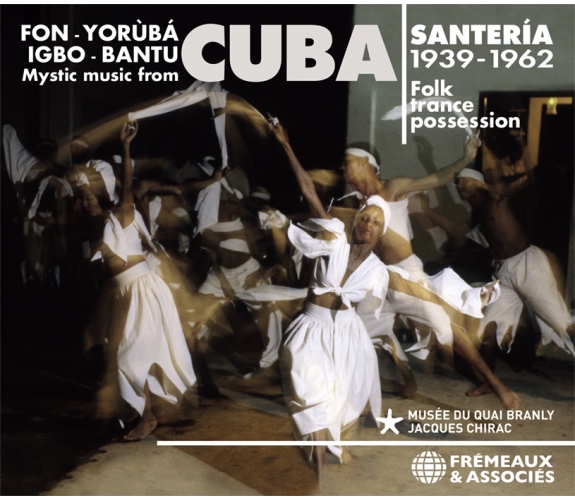

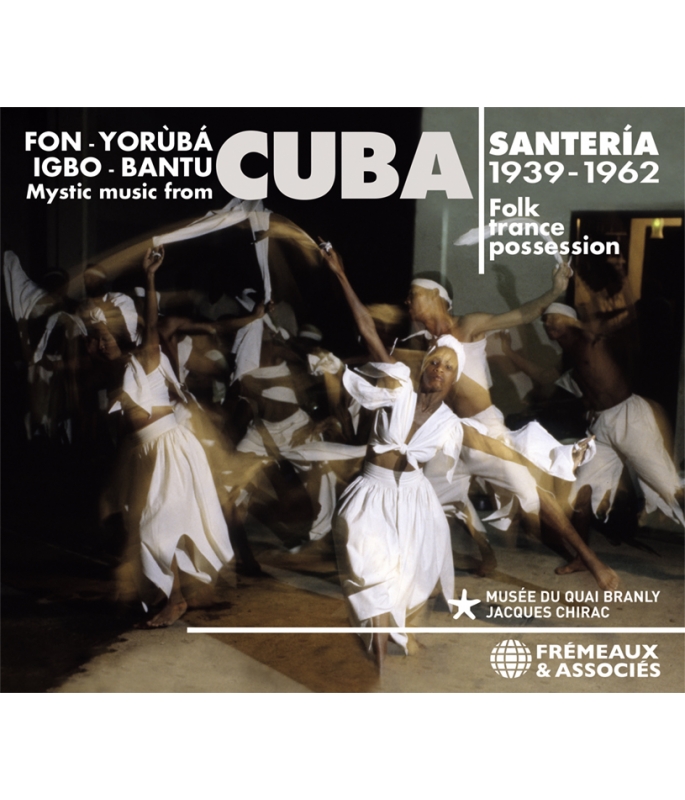

FOLK TRANCE POSSESSION - FON - YORÙBÁ - IGBO - BANTU -

Ref.: FA5791

EAN : 3561302579122

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 18 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

FOLK TRANCE POSSESSION - FON - YORÙBÁ - IGBO - BANTU -

FOLK TRANCE POSSESSION - FON - YORÙBÁ - IGBO - BANTU -

The Fon, Yorùbá, Igbo and Bantu took with them their musics and rituals, which were preserved better in Cuba than anywhere else in the Americas. Their story is deciphered by Bruno Blum in a 20-page booklet. Once mixed with Spanish culture, they became the extraordinary Afro-Cuban music; here are its roots, its essence and the best songs to the glory of the saints, the santería. On the program of the ceremony are field recordings of genuine rituals, historical studio sessions and also sacred rumba and son songs performed by the greatest — the trance of the Lucumí, Abakuá, Regla de Ochá, Regla de Ifá, Palo Congo, Arará step into your home to the banging sounds of the most intense rhythms, drums and percussions in the world.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

THE AFRO-CUBAN FOUNDING RECORDINGS BEFORE AND AFTER...

RITUAL MUSIC FROM THE FIRST BLACK REPUBLIC...

JAM SESSIONS - DESCARGAS 1956-1961

DIZZY GILLESPIE • TITO PUENTE • CAL TJADER • MACHITO...

ROOTS OF RASTAFARI 1939 - 1961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Song To Legba And YemayaTwo male voices, iya drum, atchere or aggué or abweAir Traditionnel00:03:082021

-

2Song To Orisha ChangoTwo male voices, iya drum, atchere or aggué or abweAir Traditionnel00:02:412021

-

3Abakwa SongTwo male voices, iya drum, atchere or aggué or abweAir Traditionnel00:02:462021

-

4Djuka SongTwo male voices, iya drum, atchere or aggué or abweAir Traditionnel00:00:522021

-

5Djuka DrumsTwo male voices, iya drum, atchere or aggué or abweAir Traditionnel00:00:582021

-

6Lucumi SongTwo male voices, iya drum, atchere or aggué or abweAir Traditionnel00:01:242021

-

7Blen, Blen, BlenMiguelito ValdesChano Pozo00:02:582021

-

8ZarabandaMiguelito ValdesChano Pozo00:03:032021

-

9AbasiChano PozoChano Pozo00:02:322021

-

10Placetas (Remedio Camajuani)Chano PozoChano Pozo00:02:322021

-

11TambombararanaChano PozoChano Pozo00:02:272021

-

12El CumbancheroCelia CruzRafael Hernandez Marin00:02:472021

-

13MambeCelia CruzLuis Yanez00:03:192021

-

14Saludo a EleguaCelia Cruz con La Sonora MatanceraYuli Mendoza00:03:182021

-

15Agua Pa' MiCelia Cruz con La Sonora MatanceraServia Estanislavo00:03:092021

-

16Baila YemayaCelia Cruz con La Sonora MatanceraLino Frias00:02:572021

-

17Tambores AfricanosCelina y Reutilo y su Conjunto TipicoJulio Blanco Leonard00:02:392021

-

18Bata RhythmJulio Gutierrez y OrquestaJulio Gutierrez00:05:512021

-

19Aggo EleguaSabu MartinezSabu Martinez00:04:322021

-

20AsabacheSabu MartinezSabu Martinez00:04:262021

-

21Billumba - Palo CongoSabu MartinezSabu Martinez00:06:112021

-

22Timbales y BongoMongo SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:07:122021

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Plegaria a « la RoyeCelia CruzEligio Varela00:02:582021

-

2BabaluDesi Arnaz and His OrchestraMarguerita Lecuona00:03:372021

-

3A Santa BarbaraCelina y Reutilo y su Conjunto TipicoReutilio Dominguez Terrero00:03:252021

-

4San LazaroCelina y Reutilo y su Conjunto TipicoPatricia Aguilera Sixta00:02:342021

-

5Flores para Tu AltarCelina y Reutilo y su Conjunto TipicoYuli Mendoza00:02:562021

-

6El Congo RamonCelina y Reutilo y su Conjunto TipicoAir Traditionnel00:02:262021

-

7Maria de la LuzCelina y Reutilo y su Conjunto TipicoReutilio Dominguez Terrero00:02:462021

-

8A la Reina del MareCelina y Reutilo y su Conjunto TipicoReutilio Dominguez Terrero00:02:472021

-

9BilongoSexteto La PlayaGuillermo Rodriguez Fiffe00:02:222021

-

10SimbaMartinez SabuSabu Martinez00:05:582021

-

11YeyeMongo SantamariaFrancisco Aguabella00:03:032021

-

12Chango Ta VeniCelia CruzJusti Barreto00:02:472021

-

13Oya, Diosa y FeCelia CruzJulio Banco Leonard00:02:262021

-

14AyenyeMongo SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:02:402021

-

15ImaribayoMongo SantamariaFrancisco Aguabella00:02:052021

-

16Voodoo Dance At MidnightTito Puente y su OrchestaTito Puente00:02:242021

-

17Para Tu AltarCelia CruzYuli Mendoza00:03:082021

-

18Oyeme AggayuCelia CruzAlberto Zayas00:02:512021

-

19Manana Son MananaMongo SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:04:102021

-

20Mama CalungaSexteto La PlayaRudi Calzado00:02:302021

-

21YemayaCelia CruzLino Frias00:02:412021

-

22Elegua Quiere TamboCelia CruzLuis Martinez Grinan00:03:032021

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Tele Mina For ChangoMongo SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:03:032021

-

2Agua Limpia TodoMongo SantamariaFrancisco Aguabella00:03:392021

-

3Wolenche For ChangoMongo SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:02:492021

-

4Criolla CarabaliCachao y su Orquesta CubanaGardello Gardello00:03:172021

-

5Olla de For OllaMongo SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:03:522021

-

6Yemaya Olodo For OllaMongo SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:03:412021

-

7Ochun MeneMongo SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:04:142021

-

8Yeye-o For OchunMongo SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:04:142021

-

9Cantos a EleguaConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:02:432021

-

10Rezo a OduduaConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:02:272021

-

11Rezo y Meta de ChangoConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:03:112021

-

12Cantos de YukaConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:01:392021

-

13Makutas IConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:01:132021

-

14Makutas IIConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:01:572021

-

15Rezos CongosConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:02:082021

-

16Cantos de Palo IConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:00:592021

-

17Cantos de Palo IIConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:01:592021

-

18Canto de WembaConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:02:592021

-

19Marcha de Salida EfoConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:02:082021

-

20Marcha de Salida EfiConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:02:102021

-

21Congas de ComparsasConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:03:442021

-

22PregonesConjunto Folklorico NationalAir Traditionnel00:02:452021

Cuba - Santería

Folk Trance Possession

Mystic music from Cuba, 1939-1962

Ritual music, chants, drums, invocations,

trance music, prayer and sacred songs:

Lucumí, Regla de Ochá, Regla de Ifá,

Regla de Arará, Palo Congo, Abakuá and Batá drums.

by Bruno Blum

African musics were scarcely recorded before the 1960s. There are some exceptions, but African cultures were far more preserved in Cuba than they were elsewhere in the Caribbean and as a result some of the Cuban ritual music recordings included here constitute the most ancient evidence of Yorùbá, Igbo and Bantu — among others— musical traditions. Although they slightly differ from the original African rituals because of their Creolised, often syncretic form, these recordings remain no less genuine and fascinating — and without parallel in terms of sound quality, musicianship, sophistication and intensity.

These polyrhythms allude to Afro-Cuban spirituality and traditions, i.e. in Placetas, a Camajuaní remedy, Bilongo (“wizard” in Luango) and, in the song Asabache, a lignite stone amulet, a piece of jewellery worn against the evil eye, pretty much analagous to US mojos. African musics and cultures were strictly forbidden on the North American continent except in Louisiana, and when Caribbean musics — Cuban, and also Haitian, Jamaican, etc. — showed up in the 19th century, they widely contributed in defining the modern African-American music forms: jazz, blues, rock and roll, rap, salsa, dancehall, funk, etc.

Nevertheless, as shown by these original, magnificent testimonies, substance and excitement were already right there in the Cuban volcano.

This box set offers field recordings of genuine santería rituals (which are also called Regla de ocha) cut as early as 1940; it also contains studio recordings of ritual chanting, percussion, batá drums and improvisations that ought to be compared to the US jazz form of expression1, as played by masters of Cuban music such as Chano Pozo, Mongo Santamaría, Tito Puente, Arsenio Rodríguez, Sabu and Cachao. It also contains popular songs of devotion to the saints performed by local celebrities like Miguelito Valdés on Zarabanda, the deity of mountains, and Celia Cruz in a prayer to La Roye, which is one of the names of the orisha Elegua, aka Legba the Yorùbá god of crossroads. By the way, Plegaria a “La Roye” is more than reminiscent of the famous “James Bond Theme” composed by John Barry a few months later.

Africa

From the 7th century onwards, the disproportionate expansion of the Muslim empire created a growing demand for slaves all the way from Gujarat (India) to Maghreb, present day Mali and beyond. Islamic law prevents reducing Muslims to slavery, which explains their rarity in the initial conquests of the Americas; it is also why Muslim traders specialising in slavery (notably the Hausa/Fulani people of present day northern Nigeria) turned to various Black African animist nations to get their supply of captives.

The people who were deported from the Gulf of Guinea and Congo took their most precious and fundamental possessions with them: their cultures, which were deeply anchored in religions that could not be separated from their music and their rhythms.

In the 21st century, those customs of slavery are still a reality in the northern regions of Nigeria controlled by Hausas, where criminal organisations such as Boko Haram, as well as some Red Sea Rachaida people, are kidnapping, robbing, and selling slaves in Nigeria, Cameroon, Libya, Sudan, in the Sinai peninsula and other countries in Africa and the Orient. Let us use this opportunity to pay a tribute to their victims2.

As a matter of fact, the tracks contained in this set are first and foremost musics of praise and resistance, from a time when free dancing itself was considered a subversive act (such as the Congos’ Makuta “convulsive” trance dance, which was performed by couples). Their aim was to establish a spiritual link with the spirits of the leaders, the ancestors, the cosmic divinities such as the orishas of the Yorùbá people, and pay a tribute to the African martyrs, in memory of the dead, whose spirits and recollections inspire the living. They reaffirm their culture and spirituality, and open the mind of the audience so that they listen to those spirits expressing themselves through drums and chants. Recorded in Cuba in 1940, Lucumí Song is, for example, an ancient Yorùbá chant that came directly from the western parts of Nigeria. It is sung in a Cubano-Yorùbá dialect: Lucumí is the Cuban name given to the great south Nigerian ethnic group, the Yorùbás.

Andalusian Legacy

In the Middle Ages, guilds of Islamised traders from the Mande Empire, such as the Dyulas (Arabo-Berbers descended from Hausa, Wolof, Mande, Bambara and other ethnic groups) specialised in slave trade and traffic3. Over eight hundred years after the beginning of the djihad (the “Holy War” aiming to Islamise the world), Portuguese and Spanish Catholics were the first Europeans to expand their American empires; they did this long before the French, the English, etc.

Portuguese and Spanish monarchs wished to convert the world to the Catholic religion; in turn, on January 8, 1454, Pope Nicolas V declared the Holy War on Africa and, writing a papal bull now kept in Lisbon, permitted slavery along the way. By 1494, as Christopher Columbus returned from his second voyage (he had discovered Cuba on October 28, 1492), Pope Alexander VI sanctioned the division of the world between Portugal and Spain with the Treaty of Torsedillas. Africa, Asia and Brazil went to Portugal; Spain got the rest of the Americas, including Cuba.

The Spaniards brought their contradanza musical traditions there, which were rooted in English country dance and the later French contredanse/quadrille. This became the contradanza habanera (melodies and rhythm)4. In the 19th century, this danza morphed into danzón, which dominated up to the 1920s, and has remained the official Cuban musical genre since then. After it got syncopated with Afro-Caribbean drums, the Creole contradanza had also become the basis of several Caribbean styles.

This included Haitian meringue and konpa5 as well as Dominican merengue6, which are also much loved in Cuba, Puerto Rico and other Latin countries. Castillans also brought along Andalusian scales, commonly found in Cuba (with its minor third and diminished sixth found in Arabo-Jewish-Christian and Gypsy flamenco7). They can be heard throughout this set, especially in songs by Celia Cruz and Celina y Reutilio, who also use a rhythmic legacy from the Nigeria region that has become the basis of their rumba guaguancó (compare with Tambores Africanos).

In Cuba, slavery was not abolished until 1886, which is twenty-one years after the United States. African deportation had brought animist cultures over to Cuba and these lasted in spite of the repression that followed abolition. Also, as elsewhere, animist rituals were influenced by integration.

Songs were also born, a brand of local gospel in a Creole context, a mix of several cultures heard in cancións (songs) by trovadores (troubadours) singing the glory of the saints, to the sound of Spanish guitars. West African tradition has it that the gods of the victors are respected by the vanquished, who adopt and make them their own, incorporating them into their new, syncretic religion.

Thus some of the saints (los santos) sung by Celina y Reutilio, allude to Catholic myths with a double identity.

For example: San Lazaro (who was resurrected by Jesus) and Saint Barbara (A Santa Barbara), who saw her wounds disappear after each torture (Saint Barbara is also Changó).

However, most of the orishas here have animist names used in Yorùbá and Igbo liturgy, like Elegua aka Legba or Papa Legba (deity of the crossroads), Yemayá (deity of the sea, mothers and pregnant women, as sung in Agua Pa’ Mi and A la Reina Del Mare), Abasi (Abasi Ibom, the supreme god of the Abakuás) or Oyeme Aggayu, the divinity of volcanoes (“hear me, Aggayu”). Babalú Aye, or Oya, is the healer orisha (Flores Para tu Altar and Oya, Diosa y Fe) and supreme divinity on earth8. These invocations and praising of saints, los santos, are the raison d’être of santería, to which they gave their name. Orishas are the intermediaries between Olofi, the supreme Yorùbá god, and humans.

Throughout four centuries, populations and musics have mixed in Cuba. The native Ciboneys and Guanahatabeys, as well as a great number of Taínos from Haiti, were nearly exterminated in the 16th century. Some of the survivors mixed blood with Afro-Cubans and around 1800, following the Haitian revolution many Haitian farmers in servitude were deported to the eastern tip of the island across from Haiti, bringing a French-speaking slave population to the Baracoa, Maisí and Guantanamo area.

Significant migrations of those Haitian refugees who had gone Cuban later took place in New Orleans, which contributed to disseminating a powerful Caribbean influence in Louisiana and beyond (read the booklets and listen to our Cuba in America 1939-1962, Caribbean in America 1915-1962 and Roots of Funk 1947-1962 in this series).

Animist rituals and drums in the Caribbean

A bamboula chant can be heard on Rezos Congos. “Bamboula,” now a derogatory, racist word in French, was a trendy word in the 19th century Caribbean and it left musical traces in both Haiti and Louisiana (read the booklets and listen to our Haiti - Vodou 1937-1962 and Slavery in America 1914-1972 in this series).

In New Orleans’ Congo Square, during the Spanish period (1762 to 1800), slaves were allowed to play music and practice their own religions. In principle, this was not the case in French and English colonies, where most of the African cultures were transmitted secretly — or through the Maroons, who were descended from runaway or freed slaves and lived in clandestinity, as did Brazilian Calungas, perhaps alluded to on Mama Calunga here.

On the other hand, in Cuba, following a tradition going back to the 14th century in Sevilla, guilds set up some kinds of cultural centers where Afro-Cubans could get together as ethnic groups & nations, and revive their cultures in those cabildos de nación. This allowed them to make their legacies more durable, deeper and massive, which made Cuban music all the more powerful.

The Mandingo Zape cabildo existed as early as 1568. Another cabildo was built on Havana’s Compostella Street in 1691. Slaves sang, danced and got in touch with the spirits of their ancestors there. They reached a state of trance to the sound of the drums and through their voices they expressed messages felt through invisible threads linking them to the spirits. This is what many Cubans were still doing in the 1940’s, 1950’s and 1960’s. But only when they could, as cabildos were closed down after the abolition of slavery (although some still exist in Matanzas). Drummers were oppressed by several governments and drums remained a symbol of resistance. From Venezuela to Belize, Nicaragua to Trinidad and throughout all of the Caribbean, tensions about the drums remained high, as demonising and repression hit similar drum-oriented ceremonies, and their symbol, the drum.

In Brazil, candomblé and macumba rituals and music are analogous to Cuban santería; in Jamaica, drums and traditional kumina9 rituals and the nyabinghi10 drumming of the rebel Rastafarian movement are mainly derived from Ashanti and Bantu rhythms, as many people from Congo arrived there in the 19th century. Some Mandingo and mainly Akan/Ashanti and “kromanti” traditions from present-day Ghana (now fading out after going underground for centuries) were kept alive by Jamaican Maroons; in Haiti, voodoo fed on several ethnic groups and their rituals fusioned in a unitary, Creole religion, better established than in the rest of the Caribbean as the country went independent in 1804 and voodoo has been legal there ever since11. Following migrations, Haitian voodoo has taken root in eastern Cuba and should not be mistaken for the rituals of the Arará minority originating in present day Benin.

In other American regions where Creole influence shines on, a legacy of African musical traditions can also be found, some diluted to various degrees by European influences: in Martinique, bélè (bel air) and choubal bwa (a group of “belya” percussionnists, including a clave player, play in the center of a wooden horses roundabout), in Guadeloupe it’s gwoka and in Trinidad, Yorùbá music and rituals can be found. In the US Virgin Islands some lovely quelbe songs allude to voodoo12; in New Orleans and the Georgia Sea Islands in the southern USA, work songs and negro spirituals are directly related to African musical traditions13.

On the North American continent, the omnipresence of voodoo in popular African-American music was often overlooked, although to initiates it was always a tangible reality in the 20th century14. Afro-Cubans, too, wanted to make the ritual musics of their origins durable and slowly incorporated them into their country’s popular music.

Santería

According to musician and historian Ned Sublette, the presence of four African cultural groups is still felt in Cuba at the start of the 21st century15.

a) The Yorùbás came from present day western Nigeria and eastern Benin. They descend from the great Oyó civilisation and are called Lucumí in Cuba. The Lucumí language is still spoken on the island, especially in rituals; in Celia Cruz’ song, the Mambe term, which describes coca powder consumed in Colombian rituals, more likely refers here to the Lucumí verb “meeting.” On the island their religion is called Santería, Lucumí, Regla de Ifá and Regla de Ochá.

Changó, the deity of lightning, arms, virility and drums is also a supreme divinity and can be depicted as Saint Barbara (A Santa Barbara by Celina y Reutilio), patron saint of armourers. He is often sung about in this set: in the prayer Rezo y Meta de Changó performed by the national folk group; on Changó ta Veni by Celia Cruz, Tele Mina for Changó and Wollenche for Changó by Mongo Santamaría — among others.

If the music is sufficiently intense, it can encourage the many orishas (spirits of the divinities, los santos in Spanish) to approach and possess one or more participants during the trance. Once possessed, he or she becomes a vehicle for the orisha and expresses sounds through voice along the drums. There is a specific rhythm for each orisha (there are twenty-three rhythms and dozens of saints).

They are played in ceremonies called bembés or toques and there are more than a hundred variants of them, such as the meta (Toque Oyó is about the Oyó civilisation and region in present day Nigeria, and Rezos y Meta de Changó is a ritual for Changó). Elegua aka Legba, also called Papa Legba in Haiti, is the orisha of the crossroads, where one choses the direction his life will take.

He is at the root of the myth about Robert Johnson’s song “Cross Road Blues16.” Elegua is also able to open the path to the orishas. You will hear about him in Cantos Elegua by the Conjunto Folklorico Nacional, the son Elegua Quiere Tambo performed by Celia Cruz and Aggo Elegua by Sabu. Rezo á Oduduá is a prayer to the creator of the Yorùbá world, as well as the deity of the underground world. Ochún (orisha of water and rivers, Ochún Yeye the mother) has a rhythm played on the clave, as heard on Tambombararana by Chano Pozo (and also found in later salsa music).

The high-pitched drum heard on Ochún Mene by Mongo Santamaría is the same as the classic rumba “columbia” beat. Sacred drums are only played by initiates and are called batá drums (listen to Batá Rhythm by Julio Gutiérrez). They look pretty much alike West Africa’s “talking drums” (called tama, gangan, dumdum, olondo, lunna or kalangu in Africa). The batá are related to the divinity Aña. Whenever non-sacred, analogous drums are used in popular music, they are called aberínkulas. Some of the most famous African musicians of the 20th century, including the founder of afrobeat, Fela Kuti, and King Sunny Ade (jùjú music) are Yorùbás.

b) Several Central Africa ethnic groups from present day Congo, Angola and Cameroon (called Palomonte, Briyumba or Billumba, Mosundi, Congo Real, Mundeli, Loango, Mondongo, Bafiote) speak languages related to Bantu cultures. They are called Congos in Cuba. One of them is alluded to on El Congo Ramón. Bantu animism has brought rites in which tree branches (palos) are considered containing “forces” or spirits. Their religions are called kimbisa, briyumba or Billumba, mayombe, and mostly palo (Canto de Palo). Conga drums are found throughout Cuban popular music as well as in some rituals. Their name refers to a Congolese origine, as Bantus were present in numbers as early as the end of the 16th century.

The word “conga” is also much related to the Cuban carnival, where all of the country’s cultural entities parade: Congo, Abakuá, Lucumí & Arará, as well as people of Spanish origin and others. The Bantu style played in carnivals (which was prohibited in the early 1930’s) is called “conga” music and can be heard here on Congas de Comparsas. The ngoma, ngongui and nkembi maracas are played as part of polyrhythms along with scrapers (güiro), congas (tumbas), and shekere (calabash wrapped up in a net covered in bits of wood or shells). The three Djuka Drums (also spelled Yuka, which was a dance, a vestige of fertilisation rites where pelvises banged together) are also present here.

When percussionnist Chano Pozo died in 1948, Sabu replaced him in Dizzy Gillespie’s big band and later recorded a solo album featuring the track Simba. Simba is the name of a Bantu language (in present day Gabon), traces of which can be found in palos rituals; Rezos Congos is a Congo prayer. The so-called “afro” tune El Cumbanchero is all about the participants and musicians who, in the eastern part of the island, called Oriente, created around 1860 the changüí style, which preceded the Cuban son. Those rural parties were called cumbanchas and changüí musicians originally used a tres, (a six-string guitar-like instrument where three strings are doubled with a higher octave string). They also use a marímbula (a lamellaphone or kalimba bass, also found in Jamaica where it’s called a rumba box), some maracas and a güiro (vegetable scraper rattled with a wooden stick)17.

c) The Fon (or Ewé-Fon), the Popo and the Mahi have come from what was then called Dahomey (present day Benin). They are related to Yorùbá culture and are called Arará in Cuba (Arada in Haiti). Some elements of the Yorùbá cosmology can be found in their religion called the Regla de Arará, as well as specific rituals and musics, which differ according to each ethnic group.

d) Some semi-Bantus from the Biafra region, near the city of Calabar (present day eastern Nigeria and western Cameroon), the Igbos, are called Carabalí in Cuba. They brought along with them the secret society called Abakuá.

Abakuá

In order to buy some captives, the Catholics first approached Muslim traders — and later went directly to their black suppliers in several regions. Way before they were sold in the Americas, captives came partly from war takings, partly from common law convicts, and sometimes they were used as money, in exchange for debts. If the debt was not paid back, they were sold. But raids were also set up for bare trade means. Such a violent activity was hard to justify as it could destabilise local people.

“[…] unless a sophisticated organisation was available to supply several forms of legitimation, such as the ones set up by three communities who lived together east of the Niger River. In this amphibian region where estuary forests neighbour with mangrove trees and swamps, slave trafficking took place around the Brass, Bonny and Calabar villages. The Aro controlled the oracle Aro-Chuku, who enabled them to legitimise the raids on captives. Some individuals were accused by him of witchcraft and sentenced to be devoured by the god and were in fact sold to slave traders along the coast. The Iogho, Ijaw and Ibidjo owned dugout canoes, and managed the actual captures; they went up the rivers with long canoes containing thirty rowers with rifles, standards and war drums. The Ekpe society dealt with the conformity of transactions18.”

It is in this region of Calabar, south east of present day Nigeria and western Cameroon, that around 18% of the entire Atlantic slave trade came from, and many of them were sold to the Spaniards in Cuba where they are called the Creole Carabalís (alluded to in Criolla Carabalí here)19. The persons responsible for the kidnappings had to be well-organised, because if they failed, they, in turn, ran the risk of being sold to slave traders. They were hardened and sold their captives to those sorts of secret societies comprising strictly male traders whose activities were not limited to the slave trade.

Some of these Ekpe society (also called Egbo, which means “leopard” in Ibibio) of the Efik ethnic group were sold in Cuba. They organised new networks within the islands’ slave populations and reaffirmed their power in the early 19th century. This occult fellowship is called Abakuá and practices rituals to the sound of drums called bongós.

Their members, partly white in the 21st century, are called ñáñígos (a familiar, derogatory term) and are still powerful in Cuba, especially in the Regla and Guanabacoa areas in Havana and the city of Matanza, where they amount to about 10% of the population. Their business remains secret and initiates swear to never tell about it during their lifetimes. They swear loyalty, absolute mutual aid and fidelity above any friendship or family consideration. They possess secret objects, among which are the sacred drums named Ekue, Ekueñon, Sese-Eribo and Empegó. Drums are sacred because the divinities talk through them when they are played by the Iyambas (percussionist initiates)20.

Abakuá, the religion praising the god Ekue, is the work of the Iyamba, who makes no pledge. He gives strength to the Mokongo (“the wood”) through the power of his magic and is himself freed of the punishments threatening others. These penalties are caused by his magic also and can therefore not affect him. Ñáñígos use a secret, mysterious language and sing it during their ceremonies called plantes.

It can be heard here on Canto de Wemba and Marcha de Salida Efó (named after the Efó tribe), Marcha de Salida Efí (named after the rival Efí tribe) performed by the Conjunto Folklorico Nacional, as well as on Criolla Carabalí and Billumba. Canto de Wemba is supposed to follow a procession of the members, thus completing the initiation of new disciples, who drink the blood of a cockerel whose throat is cut on the spot. Ñáñígos also parade at the Cuban carnival, wearing highly colourful, checked outfits, which is yet another tradition where drums and percussion are played.

Abakuá music has left a deep mark on Afro-Cuban popular music. Combined with Bantu influences, it has contributed to creating the local rumba tradition, especially the guaguancó style and its rhythms, which are distinctly played on the clave.

Guaguancó is the Cuban name of the acacia corniguera tree, which is related to the god Ogún, to Oduwawa, the founder of Yorùbá religion and Obatalá, the father of all deities in Yorùbá cosmology. In Ned Sublette’s own words, to the White society of the early 20th century, hearing Abakuá bongós in son music (which was the new Cuban popular music then), equalled the shock of gangsta rap in the American high society at the end of the century 21.

A controversy had actually broken out among ñáñígos, as some members felt that sacred rhythms played in their rituals ought not be used in secular music22. The legendary percussionist Chano Pozo, who was a fervent Changó devotee, had refused to become a santería initiate before he went back to New York in 1948. A Lucumí drums master and an Abakuá member, he had recorded with Milt Jackson, James Moody, Machito and Dizzy Gillespie and had joined the latter’s orchestra.

Chano Pozo was the eccentric, emblematic bad boy in “cubop,” the dazzling Afro-Cuban modern jazz of that era. A man from the streets, a dancer, bongós player and fine tumbalero from the roughest neighbourhood, Pozo was a violent man. He was shot dead by six bullets in a New York bar by a marijuana dealer who’d ripped him off the day before. Chano had knocked him out with a single blow of his fist — then took his money back out of the man’s pocket.

God of arms, lightning and war, Changó/Santa Barbara’s day is December 4. Chano Pozo had died at the sound of thunder and the flash of lightning on December 2, just a few hours before it; In Cuba, many thought that he ought to have accepted a santería initiation following the warnings of a babalao (Lucumí Changó priest) before unveiling the sacred rhythms that made him rich and famous.

In Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra he was replaced by another Cuban man named Sabu, who recorded an album of ritual music (excerpts included here) with the legendary blind man Arsenio Rodríguez, one of the influential founders of the son montuno style, and a pioneer of the “conjunto,” the epochal, modern, small Cuban band of the 1940s. Grandpa Arsenio can be heard chanting Abakuá language on Billumba. Along with Mario Bauza and Chano Pozo, they had brought Abakuá rituals to New York studios and, who knows, perhaps they, in turn, have since secretly taken control of New York, Miami — or both.

Tito Puente, a New Yorker born of Puerto Rican origin, lead the best Cuban orchestra in the United States. His tune Voodoo Dance at Midnight shows the reverb-abounding, more commercial, US face of the genre. In this sense, and along with White Cuban star of American TV, Desi Arnaz, he contributed to the “exotica” trend that swept the USA at the time, with Martin Denny and Arthur Lyman’s hits. After the 1959 revolution, many Cuban artists, including Celia Cruz, fled to the USA, bringing along the real thing, and soon created a new, enduring trend: salsa.

Bruno Blum, April, 2018.

Thanks to Chris Carter for proofreading, Crocodisc, Franck Jacques, Bernard Loupias, Norbert “Nono” Nobour, Pascal Olivese and Frédéric Saffar.

© Frémeaux & Associés 2021

1 Read the booklet and listen to Cuba - Jazz 1956-1961, Jam sessions, Descargas in this series.

2 Source : RFI, Amnesty International, Walk Free Foundation, OIT and OIM.

3 Olivier Petre-Grenouilleau, Les Traites négrières (Paris, Gallimard, 2004).

4 Maya Roy, Cuban Music (Latin America Bureau, London, 2002).

5 Read the booklet and listen to “Contre danse N°4” by Nemours Jean-Baptiste on Haiti - Meringue et Konpa 1952-1962 in this series.

6 Read the booklet and listen to Dominican Republic - Merengue 1949-1962 in this series.

7 Read the booklet and listen to Flamenco 1952-1961 in this series.

8 Also read the booklet and listen to Slim Gaillard’s version of “Babalú” on Cuba in America 1939-1962 in this series.

9 Read Bruno Blum’s booklet and listen to Jamaica - Folk Trance Possession 1939-1961, Mystic Music From Jamaica, Roots of Rastafari, which was co-published by the musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac in this series.

10 Read the booklet and listen to Africa in America 1920-1962, Rock, Jazz & Calypso in this series.

11 Read Bruno Blum’s booklet and listen to Haiti - Vodou 1937-1962 Folk Trance Possession, Ritual Music From the First Black Republic, which was co-published by the musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac in this series.

12 Read the booklet and listen to Virgin Islands - Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960 in this series

13 Read Bruno Blum’s booklet and listen to Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972, work songs, folk, spirituals, calypso, blues, jazz, R&B, which was co-published by the musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac in this series.

14 Read the booklet and listen to Voodoo in America 1926-1961, blues, jazz, rhythm & blues, calypso in this series.

15 Ned Sublette, Cuba and its Music, From the First Drums to the Mambo (Library of Congress, 2004).

16 Listen also to the song “Papa Legba” and watch its video by this writer, Bruno Blum.

17 El Cumbanchero, by Puerto Rican composer Rafael Hernandez, has also become a reggae classic under the name “Rockfort Rock”.

18 Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau (ibid.).

19 “Criolla Carabalí” includes improvisations in the “descarga” style — Cuban jazz. Read the booklet and listen also to Cuba - Jazz 1956-1961, Jam Sessions-Descargas in this series.

20 Patrick Taylor, Frederick I. Case, The Encyclopedia of Caribbean Religions (University of Illinois Press, 2013).

21 Ned Sublette (ibid).

22 Ned Sublette (ibid).

Cuba - Santería 1939-1962 - Discography

Disc 1 Ritual music and mystic songs

Acetate field recordings1940

Two male voices, iya drum, atchere or aggué or abwe (aka shekere).

Tracks 1 to 6 recorded by Harold Courlander in Havana, Guanabacoa and Matanzas Province, Cuba, 1940. Folkways Records, FE 4410.

1. Song To Legba And YemayÁ

(unknown)

Male chorus, drums.

2. Song To Orisha ChangÓ

(unknown)

Male chorus, drums. Guanabacoa, Cuba, 1940.

3. Abakwa Song

(unknown)

Drums, chorus.

4. Djuka Song

(unknown)

Three drums.

5. Djuka Drums

(unknown)

6. LucumÍ Song

(unknown)

Two male voices, iya drum, atchere or aggué or abwe (aka shekere).

Acetate studio recordings 1939-1950

Miguelito Valdés con la Orquesta de la Playa

Miguelito Valdés-v; Guillermo Portela-dir.; Walfredo de los Reyes, Luis Rubio-tp; Liduvino Pereira-cl, as, cg; Evelio Gonzales-ts; Ernesto de la Vega-g, mar; Anselmo Sacasas-p; “Pepsi Cola»-b; Ramoncito Castro-cg. Habana, October, 1939.

7. Blen, Blen, Blen [rumba afro]

(Luciano Pozo aka Chano Pozo)

Miguelito Valdès with Machito and his Afro-Cubans

Miguelito Valdés-v; Francisco Raúl Gutiérrez Grillo aka Machito-dir., mar; Bobby Woodlen-tp; Mario Bauzá-tp, arr.; Gene Johnson, Johnny Nieto-as; José Madera aka Pin-ts; Frank Gilberto Ayala-p; Julio Ondino-b; Tony Escollies aka El Cojito-cg; Bilingüe-bg. New York, July 27, 1942.

8. Zarabanda [orisha of the mountains]

(Luciano Pozo aka Chano Pozo)

Chano Pozo y su Ritmo de Tambores

Luciano Pozo aka Chano Pozo-cg, v; Miguelito Valdés-cg, v; Kike Rodríguez-cg, v; Carlos Vidal-cg; José Mangual-bg. New York, February 4, 1947.

9. Abasi [supreme yoruba orisha; ‘ritmo afro-cubano N.2’]

(Luciano Pozo aka Chano Pozo)

10. Placetas (Remedio Camajuaní) [rumba columbia; ‘ritmo afro-cubano N.4’]

(Luciano Pozo aka Chano Pozo)

11. Tambombararana [rumba columbia; ‘ritmo afro-cubano N.3’]

(Luciano Pozo aka Chano Pozo)

Celia Cruz con Leonard Melody

Úrsula Hilaria Celia Caridad de la Santísima Trinidad Cruz Alfonso aka Celia Cruz-v; Orquesta Leonard Melody, possibly Julio Blanco Leonard-dir. Turpial 45-343 A&B [S-343 A&B](Venezuela). Havana, circa 1950.

12. El Cumbanchero [afro]

(Rafael Hernández Marín)

13. Mambe [afro mambo]

(Luis Yánez)

Studio tape recordings 1951-1958

Celia Cruz

Celia Cruz-v; La Sonora Matancera, Havana, circa 1950.

14. Saludo a Elegua [orisha of the roads and crossroads]

(July Mendoza aka Yuli Mendoza)

La Sonora Matancera con Celia Cruz

Celia Cruz-v; La Sonora Matancera orchestra. Havana, circa 1951.

15. Agua Pa’ Mi [on Yemaya, orisha of the mothers; guaracha]

(Estanislavo Servia)

16. Baila YemayÁ [orisha of the mothers]

(Lino Frias)

Celina y Reutilio y su Conjunto Típico

Celina Gonzáles-v; Reutilio Domínguez Terrero-g; tres, p, cg, perc, chorus. Sua Ritos LS-103. Habana, 1956.

17. Tambores Africanos [on Changó, orisha of lightning and war; rumba guaguancó]

(Julio Blanco Leonard)

Julio Guttiérez y su Orquesta

Julio Gutiérrez, dir.; Jesus Ezquijarrosa aka Chuchu-timbales; Óscar Valdés-bongos; Marcelino Valdés-congas; Walfredo de los Reyes, Jr.-d; percussion; vocal chorus. Recorded by Fernando Blanco, Edwin Fernandez De Castro. Taken from the album Cuban Jam Session Panart LD-3055. Habana, 1956.

18. BatÁ Rhythm

(Julio Gutiérrez)

Sabu

Arsenio Rodriguez-lead v on 21, cg; Sarah Baro-v; Louis Martinez aka Sabu-cg, llamador on 21, bg, v; Raul Travieso aka Caesar-cg, quinto on 21, v; Israel Moises Travieso aka Quique-cg, golpe on 21; Ray Romero aka Mosquito-cg; Evaristo Baro-b. Recorded by Rudy Van Gelder, Hackensack, New Jersey, 1957. Blue Note 1561.

19. Aggo Eleguá [orisha of the crossroads, roads]

(Louis Martinez aka Sabu)

20. Asabache

(Louis Martinez aka Sabu)

21. Billumba - Palo Congo

(Louis Martinez aka Sabu)

Mongo Santamaría

Ramón Santamaría as Mongo Santamaría, dir., timb, bg; Carlos Vidal Bolado, Francisco Aguabella, Israel del Pino, Modesto Duran, Pablo Mozo-drums and percussion; William Correa aka Willie Bobo-timb. Taken from the album Yambú, Fantasy F-8012. Fantasy Studio, Berkeley, California, December 1959.

22. Timbales y BongÓ

(Ramón Santamaría aka Mongo Santamaría)

Disc 2 Mystic Songs 1954-1962

Celia Cruz

Úrsula Hilaria Celia Caridad de la Santísima Trinidad Cruz Alfonso aka Celia Cruz-v; Orquesta La Sonora Matancera. Habana, 1954.

1. Plegaria a “La Roye»

(Eligio Varela)

Desi Arnaz and his Orchestra

RCA Victor WP 198. Hollywood, California, 1953.

2. BabalÚ - [rumba guaguancó]

(Margarita Lecuona)

Celina y Reutilio y Su Conjunto Tipico

Celina Gonzáles-v; Reutilio Domínguez Terrero-g; tres, p, cg, perc, chorus. Sua Ritos LS-103. Habana, 1956.

3. A Santa Barbara - [rumba guaguancó]

(Reutilio Domínguez Terrero)

4. SAN LAZARO

(Sixta Patricia Aguilera)

5. Flores Para tu Altar - [rumba guaguancó]

(July Mendoza aka Yuli Mendoza)

6. El Congo RamÓn - [rumba guaguancó]

(unknown)

7. Maria de la Luz - [rumba guaguancó]

(Celina Gonzáles, Reutilio Domínguez Terrero)

8. A la Reina del Mare - [rumba guaguancó]

(Celina Gonzáles, Reutilio Domínguez Terrero)

Sexteto La Playa

Marie & Paul-v; Raymond Mantilla aka Ray Mantilla-cg; tp, tb, g. Mardi-Gras 1028-X 45. Habana, 1957.

9. Bilongo [mambo]

(Guillermo Rodríguez Fiffe)

Sabu

Louis Martinez aka Sabu-cowbell, v; Willie Capo-v, whistle; Arsenio Rodriguez-cg; Raul Travieso aka Caesar-cg, v; Israel Moises Travieso aka Quique-cg; Ray Romero aka Mosquito-cg. Recorded by Rudy Van Gelder, Hackensack, New Jersey, 1957. Blue Note 1561.

10. Simba [Bantu language of Gabon]

(Louis Martinez aka Sabu)

Mongo Santamaría

Mercedes Hernandez-v; Ramón Santamaría as Mongo Santamaría, Carlos Vidal Bolado, Francisco Aguabella, Israel del Pino, Modesto Duran, Pablo Mozo, William Correa aka Willie Bobo-drums and percussion; vocal chorus. Taken from the album Yambú, Fantasy F-8012. Fantasy Studio, Berkeley, California, December 1959.

11. Yeye

(Francisco Aguabella)

Celia Cruz con la Sonora Matancera

Celia Cruz-v; La Sonora Matancera orchestra. Seeco 45-7805. Habana, 1958.

12. ChangÓ Ta VenÍ [guaracha]

(Justí Barreto)

13 Oya, Diosa y Fe [orisha Babalú]

(Julio Banco Leonard)

Mongo Santamaría

Possibly Israel Pino-v; Niño Rivera-tres; Ramón Santamaría as Mongo Santamaría-cg, bg, perc, dir.; Armando Peraza-cg, bg, perc.; William Correa aka Willie Bobo-timb, bg; Francisco Aguabella-cg, perc.; Modesto Duran-cg, perc.; Carlos Vidal-cg, perc.; vocal chorus. Taken from the album Mongo, Fantasy F-8032. Fantasy Studio, Berkeley, California, May 1959.

14. Ayenye - Mongo Santamaría

(Ramón Santamaría aka Mongo Santamaría)

15. Imaribayo - Mongo Santamaría

(Francisco Aguabella)

Tito Puente

Bernie Glow, Carl Severinsen aka Doc, Ernest Royal, Jimmy Frisaura, Patrick Larrusso, Pedro Boulong aka Puchie-tp; Seymour Berger-tb; Roberto Rodriguez-b; José Mangual, Sr., Louis Perez aka Chickie-bg; Carlos Valdez aka Patato, Ray Barreto-cg; Ernesto Antonio Puente, Jr. aka Tito Puente-timb, leader; Willie Rodriguez-d; Produced by Marty Gold. Taken from the album Tambó, RCA Victor DKL1-3174. New York, April 21, 1960.

16. Voodoo Dance at Midnight

(Ernesto Antonio Puente, Jr. aka Tito Puente)

Celia Cruz con la Sonora Matancera

Celia Cruz-v; La Sonora Matancera orchestra. Habana, circa 1960.

17. Para Tu Altar

(July Mendoza aka Yuli Mendoza)

18. Oyeme Aggayu - Celia Cruz

(Alberto Zayas)

Mongo Santamaría

Carlos Embales-v, perc; Mercedita Valdés-v; Mario Arenas, Finco, Armando Raymat, Cheo Junco, Luis Santamaria, Macuchu-vocal chorus; William Correa aka Willie Bobo-bongo, timbales; Yeyito-bongos; Gustavito-güiro; Ramón Santamaría as Mongo Santamaría-cg, timb, dir. Taken from the album Mongo in Havana- Bembé!, Fantasy 3311. Havana, Cuba, 1960.

19. Mañana Son Mañana [rumba guaguancó]

(Ramón Santamaría aka Mongo Santamaría)

Sexteto La Playa

Marie & Paul-v; Raymond Mantilla aka Ray Mantilla-cg; tp, tb, g. Havana, circa 1961.

20. Mama Calunga

(Pedro Calzado aka Rudy Calzado)

Celia Cruz con la Sonora Matancera

Celia Cruz-v; La Sonora Matancera orchestra. Habana, circa 1962.

21. YemeyÁ

(Lino Frias)

22. Elegua Quiere TambÓ

(Luis Grinan)

Disc 3 Ritual music, drums, invocations and prayers 1960-1962

Mongo Santamaría

Same as disc 2, 19.

1. Tele Mina for ChangÓ

(Ramón Santamaría aka Mongo Santamaría)

2. AGua Limpia TODO - Mongo Santamaría

(Francisco Aguabella)

3. Wolenche for ChangÓ - Mongo Santamaría

(Ramón Santamaría aka Mongo Santamaría)

Cachao

Lead v, vocal chorus may include: Alfredo León, Adelso Paz Rodriguez aka Rolito, Orlando Reyes, Estanislao Laíto Sureda Hernandez aka Laíto Sureda aka Laíto Sr., Pachungo Fernández, Memo Furé, Gerardo Portillo. Possibly: Niño Rivera-tres; Israel López Valdés aka Cachao-b, dir.; Federico Arístides Soto Alejo aka Tata Güines or Ricardo Abreu aka Los Papines-cg; Guillermo Barreto-timb; Rogelio Iglesias aka Yeyo-bongos; Gustavo Tamayo-güiro; Maype US-168. Havana, circa 1960.

4. Criolla CarabalÍ - [ritmo abakuá, descarga]

(G. Gardello)

Mongo Santamaría

Same as disc 2, 19.

5. Olla de for Olla - Mongo Santamaría

6. Yemaya Olodo for Olla - Mongo Santamaría

7. OchÚn Mene - Mongo Santamaría

8. Yeye-O for OchÚn - Mongo Santamaría

Conjunto Folklorico Nacional

Traditional songs. Studio recordings.

9. Cantos Á Eleguá [Yoruba music]

10. Rezo Á OduduÁ [Yoruba music]

11. Rezo y Meta de ChangÓ [Yoruba music]

12. Cantos de Yuka [Conga music]

13. Makutas I [Conga music]

14. Makutas II [Conga music]

15. Rezos Congos [bamboula, Conga music]

16. Cantos de Palo I [Conga music]

17. Cantos de Palo II [Conga music]

18. Canto de Wemba [Abakuá music]

19. Marcha de Salida EfÓ [Abakuá music]

20. Marcha de Salida EfÍ [Abakuá music]

21. Congas de Comparsas [rumba]

22. Pregones [prayers]

Five prayers:

Yerbero: medicinal herbs street vendor (yerbero) prayer

Escobero: broom vendor or chimney sweeper chant

Manguero: mango vendor prayer

Frutero: fruit vendor prayer

Bollera: prayer of a Black lady selling fried food