- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

ELLA FITZGERALD • LOUIS ARMSTRONG • NINA SMONE • OSCAR PETERSON • MILES DAVIS,…

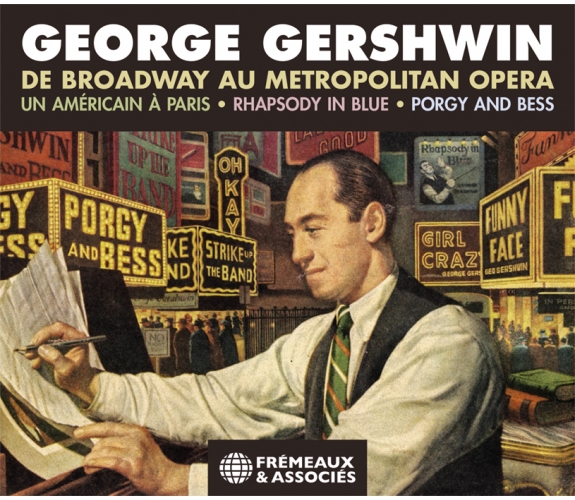

GEORGE GERSHWIN

Ref.: FA5792

Artistic Direction : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 38 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

ELLA FITZGERALD • LOUIS ARMSTRONG • NINA SMONE • OSCAR PETERSON • MILES DAVIS,…

ELLA FITZGERALD • LOUIS ARMSTRONG • NINA SMONE • OSCAR PETERSON • MILES DAVIS,…

As early as the 1920s, the musicals, concert pieces and the opera Porgy & Bess composed by George Gershwin contributed to the making of the Great American Songbook. The proof of Gershwin’s immense talent is in the fact that his music never went into purgatory after his premature death in 1937 at the age of 39. While his concert pieces are still performed by soloists and formations from the world of classical music, those who best defend the art of Gershwin remain the artists and musicians of the jazz world.

Teca CALAZANS et Philippe LESAGE

A CENTURY OF GLORY : 1898 - 1998

ELLA FITZGERALD • SARAH VAUGHAN • CHET BAKER • MILES...

FROM GLENN MILLER STORY TO THE PINK PANTHER...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1I Loves You PorgyNina SimoneGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:04:091958

-

2But Not For Me (Erroll GarnerErroll GarnerGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:381956

-

3My Man's Gone NowBill EvansGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:06:241961

-

4Nice Work If You Can Get ItSarah VaughanGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:381950

-

5SummertimeDuke EllingtonGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:501961

-

6The Man I LoveBillie HolidayGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:031939

-

7It Ain't Necessarily SoAretha FranklinGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:511961

-

8I Loves You Porgy 2Billie HolidayGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:581948

-

9The Man I Love 2Don ByasGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:441951

-

10Embraceable YouChet BakerGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:091957

-

11They All LaughedChet BakerGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:111957

-

12How Long Has This Been Going OnChet BakerGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:04:101958

-

13Summertime 2Lonnie JohnsonGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:281960

-

14It Ain't Necessarily So 2Miles DavisGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:04:251958

-

15My Man's Gone Now 2Miles DavisGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:06:151958

-

16Gone, Gone, GoneMiles DavisGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:031958

-

17I Loves You Porgy 3Miles DavisGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:04:021958

-

18Bess, You Is My Woman NowMiles DavisGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:05:141958

-

19GoneMiles DavisGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:401958

-

20Summertime 3Miles DavisGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:181958

-

21There's A Boat Dat's Leavin' Soon For New York To New YorkMiles DavisGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:261958

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Summertime 4Ella FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:04:581958

-

2I Wants To Stay HereElla FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:381958

-

3It Ain't Necessarily So 3Ella FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:06:341958

-

4My Man's Gone Now 3Ella FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:04:021958

-

5I Got Plenty O Nuttin'Ella FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:521958

-

6Bess, You Is My Woman Now 2Ella FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:05:281958

-

7A Woman Is A Sometime ThingElla FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:04:471958

-

8Oh Doctor JesusElla FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:001958

-

9Buzzard SongElla FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:581958

-

10What You Want Wid BessElla FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:01:591958

-

11There's A Boat Dat's Leavin' Soon For New York 2Ella FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:04:541958

-

12O Bess, Oh Where's My BessElla FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:361958

-

13Oh Lawd, I'm On My WayElla FitzgeraldGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:02:561958

-

14I Got Plenty O' Nuttin 2Oscar PetersonGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:06:231959

-

15Wants To Stay HereOscar PetersonGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:06:201959

-

16There's A Boat Dat's Leavin' Soon For New York 3Oscar PetersonGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:07:111959

-

17Bess, You Is My Woman Now 3Oscar PetersonGeorges & Ira Gershwin00:03:301959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Un Americain à ParisFelix SlatkinGeorges Gershwin00:17:581956

-

2Concerto en Fa - AllegroDaniel WayenbergGeorges Gershwin00:13:081960

-

3Concerto en Fa - AndanteDaniel WayenbergGeorges Gershwin00:13:021960

-

4Concerto en Fa - Allegro, 3e mouvementDaniel WayenbergGeorges Gershwin00:07:001960

-

5Rhapsody In BlueDaniel WayenbergGeorges Gershwin00:16:171960

FA5792

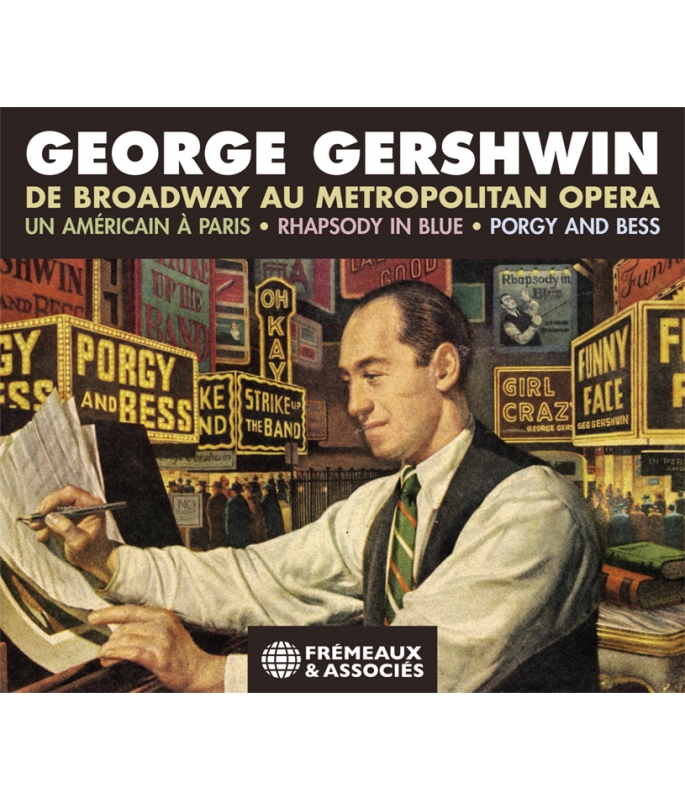

George Gershwin

de Broadway au MEtropolitan Opera

un américain à paris • RHAPSODY IN BLUE • PORGY AND BESS

Avec ses comédies musicales, ses pièces de concert et son opéra Porgy & Bess, George Gershwin contribue, dès les années 1920, à l’élaboration du grand roman musical américain. Preuve de son immense talent, sa musique ne connaîtra jamais le purgatoire après sa mort précoce en 1937, à l’âge de 39 ans. Si ses pièces de concert sont toujours données par les solistes et les orchestres de musique classique, ce sont bien les artistes du monde du jazz qui défendent le mieux son art.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

As early as the 1920s, the musicals, concert pieces and the opera Porgy & Bess composed by George Gershwin contributed to the making of the Great American Songbook. The proof of Gershwin’s immense talent is in the fact that his music never went into purgatory after his premature death in 1937 at the age of 39. While his concert pieces are still performed by soloists and formations from the world of classical music, those who best defend the art of Gershwin remain the artists and musicians of the jazz world.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

George Gershwin

de Broadway au MET (Metropolitan Opera)

Le secret de son art : l’entre -deux

Les compositeurs sont rarement tendres envers leurs confrères ; qu’on en juge avec les propos rapportés de Virgil Thomson, compositeur américain aujourd’hui bien oublié : « George Gershwin n’est pas un compositeur très sérieux ; il ne sait même pas ce qu’est un opéra » ; jugement sévère s’il en est mais il ajoute immédiatement un correctif, marque de son étonnement : « pourtant, Porgy & Bess est un opéra, plein d’énergie et de vigueur ». Soit un jugement dont l’écartèlement entre incompétence, ignorance et résultat artistique inattendu poursuivra Gershwin toute sa vie. Le secret de son art ne résiderait-il pas justement dans cette ambivalence, dans cette singularité d’un style indéfinissable tapi entre musique populaire et musique sérieuse ?

C’est l’illustration de cet entre-deux que nous abordons dans cette anthologie. On y entendra ce que les américains appellent des « songs » reprises par des musiciens de jazz aux côtés d’œuvres répertoriées comme « savantes », ici interprétées par des artistes du monde de la musique classique. Pièce maîtresse justificatrice de l’ambivalence, l’opéra Porgy & Bess trouvera dans les relectures données par Louis Armstrong et Ella Fitzgerald ou, plus encore, par Miles Davis et Gil Evans une bonification de l’ouvrage lyrique sans en trahir son esprit.

Bien que Gershwin reste le héraut de la musique populaire américaine apparue lors des années 1920, cela n’interdit pas les notations négatives jusqu’à nos jours ; ainsi Renaud Machart, le critique musical du Monde, producteur à France Musique et auteur de biographies de Leonard Bernstein et de Stephen Sondheim, écrit : « En dépit de son génie mélodique et harmonique, il ne possédait pas le bagage technique suffisant pour la rédaction d’œuvres savantes ». Et Jacques Drillon, qui fut le critique musical du Nouvel Observateur, d’ajouter en 1998 : « Porgy & Bess, opéra de 1935 est une parfaite cochonnerie. Comme tout ce qu’a écrit Gershwin. Du toc authentique ». L’autodidacte lucide qu’était George Gershwin n’aurait pas pris ombrage de ces commentaires, tout en cherchant sans cesse à obtenir des conseils voire des enseignements auprès de maîtres comme Stravinski ou Ravel. Il ira jusqu’à déclarer, sans forfanterie ni fausse pudeur : « J’ai la modeste prétention de contribuer à l’élaboration du grand roman musical américain ». Et certains de corroborer cette assertion, comme Marin Aslop (« Si on regarde Porgy & Bess, on voit que Gershwin déployait son écriture vers toutes les formes possibles ») ou Bernstein (« Je reconnais Gershwin dès la première mesure. La voix d’un génie ») sans oublier Schoenberg (« Que Gershwin ait été un novateur, cela est évident. Ce qu’il a su tirer du rythme, de l’harmonie et de la mélodie ne constitue pas seulement un style ; c’est quelque chose de foncièrement différent du maniérisme de maints compositeurs dits sérieux ».).

La gestation artistique

L’idée première de cette anthologie fut de réaliser une variation autour de Porgy & Bess, cet ouvrage inspiré de la pièce d’Edwin DuBose Heyward, un écrivain originaire de Caroline du Sud. Parce que c’est le dernier ouvrage majeur de Gershwin, qu’il a connu de pures versions lyriques (avec Leontyne Price, entre autres) et des relectures passionnantes, mais aussi parce que ce chef d’œuvre d’art lyrique américain imprégné de jazz, de musique folk et d’influences européennes, n’avait pas été donné au Metropolitan Opera de New York depuis des lustres, anomalie réparée en février 2020 avec une production de James Robinson, sous la baguette de David Robertson et avec une distribution (« cast ») entièrement afro-américaine comme le voulaient George et Ira Gershwin.

Mais avant d’en revenir à Porgy & Bess, brossons le parcours de vie de Gershwin qui va nous permettre de comprendre comment il passera des comédies musicales des théâtres de Broadway au Carnegie Hall et au Met. La dizaine de pages qu’Alex Ross lui consacre dans son livre The Rest is Noise est une merveilleuse synthèse de la gestation de l’art du compositeur. Gershwin est né dans le Lower East Side de Manhattan, où régnait un métissage de culture russe, d’Europe Centrale, yiddish, noire et américaine de souche. Sauvé à l’adolescence de la mauvaise influence de la rue par l’étude du piano, il est l’homme en qui les tendances les plus antagonistes du moment parviennent à fusionner harmonieusement : l’énergie propre qui caractérise New York, les « songs » de Tin Pan Alley et le ragtime qui suintent des gargotes. Ce juif d’origine russe qui se sent profondément américain laïc, assimilé, est un des rares musiciens blancs du temps qui reconnaisse dans le jazz un art majeur ; il aime Art Tatum et Bessie Smith, et il est un enfant du ragtime fasciné par Scott Joplin, Eubie Blake ou James P Johnson. Comme le souligne Alex Ross : « Ne pas choisir : voilà l’essence même de son génie, lui, qui tout le temps partagea sa vie entre théâtre musical et pièces de concert, entre « grande musique » et « entertainment », entre culture américaine et proximité avec les milieux immigrés ».

Broadway

C’est à Broadway que s’épanouit le talent de George Gershwin. Son succès sera tel qu’une année, six de ses comédies musicales sont jouées en même temps sur les scènes de Broadway. Du premier « musical » La-La- Lucille (1919 ; livret : Fred Jackson, lyrics : Buddy DeSylva et Irving Caesar) à Let’ Em Eat Cake de 1933 en passant par Oh ! Lady Be Good (1924), Oh, Kay ! (1926) ou Girl Crazy (1930), les comédies musicales vont offrir les songs qui seront reprises par les plus grandes voix et les meilleurs solistes du jazz. En 1924, avec l’écriture des lyrics de Oh Lady Be Good, Ira Gershwin va devenir le partenaire constant de George. Ira est un personnage rondouillard à la personnalité fort éloignée de l’actif George. Grand lecteur placide, il est toujours de bon conseil et il ne manque pas d’humour. Les frères Gershwin resteront quelques mois à Hollywood où ils signeront les chansons de Shall We Dance auquel participe leur ami Fred Astaire (les titres à retenir : They All Laughed et They Can’t Take That Way From Me). Cette large part du répertoire, qui va nourrir le Great American Songbook (Fascinating Rhythm ; Lady Be Good, But Not For Me, Love Is Here To Stay, I’ve Got A Crush On You, Nice Work If You Can Get it pour ne citer que quelques titres) est indispensable pour cerner le génie d’un compositeur qui sentit néanmoins le désir impérieux de s’aventurer vers les terres de la musique dite savante.

Rhapsody In Blue

C’est avec la Rhapsody In Blue que George Gershwin, qui n’a que 25 ans, va s’immiscer dans le monde de la musique classique. Sa réputation est alors confidentielle mais il va trouver en Paul Whiteman le commanditaire d’une partition « classique », une espèce de concerto avec des couleurs jazz. Elle sera donnée dans le cadre d’une soirée huppée (présence de Rachmaninoff, Stokowski et Sascha Heifetz, entre autres) baptisée « An Experiment In Modern Music ».

Rhapsody In Blue est une pièce en forme rhapsodique libre en un mouvement. Composée par Gershwin, elle est orchestrée par Ferdinand – Ferde – Grofé. « Ce n’est pas une musique à programme, précise Gershwin, mais une musique impressionniste. J’ai essayé d’exprimer notre cadre de vie, le tempo de notre quotidien, avec sa vitesse, son chaos, sa vitalité. Je n’ai pas essayé de traduire par des sons des tableaux précis ». C’est en référence aux peintures impressionnistes de James Whistler que Ira Gershwin conseille d’inclure dans le titre la notation : In Blue. Bernstein commentait : « les thèmes sont extraordinaires mais la Rhapsody n’est pas une vraie composition au sens où tout ce qui arrive doit apparaitre inéluctable ». Il est vrai qu’il s’agit plus d’une sorte de collage combinant jazz (à faire hurler les puristes) et musique classique orchestrale (à faire hurler les mélomanes). Il n’en reste pas moins que ce concert qui eut lieu le 12 février 1924 à l’Aeolian Theatre de New York a reçu un accueil délirant. A n’en pas douter, l’étrange glissando suggéré par le clarinettiste Ross Grosman a fait son petit effet. La composition a été réalisée en 18 jours pour deux pianos et sur scène l’orchestre comprend 33 musiciens. N’oublions pas, pour tout mettre en perspective, qu’en 1922, Varèse composait Amériques.

Un Américain à Paris

Lors de son séjour parisien à l’hôtel Majestic, en 1928, Gershwin conçoit les premières esquisses d’un Américain à Paris, un ouvrage à la structure plus ambitieuse et mieux construite que Rhapsody In Blue. L’écriture reste gravée dans l’esprit du ragtime (la naissance du style swing est postérieure). Cette fois-ci, Gershwin assure et la composition et l’orchestration et il précise que ce ballet rhapsodique « constitue la musique la plus moderne que j’ai tenté de composer ».

Elle est donnée le 13 décembre 1928 au Carnegie Hall (certains critiques patentés parleront de « babillages innocents et pénibles ») et le premier enregistrement est réalisé en 1929 sous la direction de Nathanaël Shilkert pour RCA. En 1951, Vicente Minelli tourne un film avec Gene Kelly, Leslie Caron et Georges Guétary qui lancera la notoriété définitive de l’ouvrage.

Pour ce ballet en trois parties mais en un seul mouvement, à la délicieuse insouciance et où la pulsation souligne le mouvement profond de l’œuvre, l’orchestre sans piano comprend trois saxophones, quatre klaxons aux sons différenciés de taxis parisiens, flûte ; hautbois, cor anglais, clarinettes, bassons, cors, trompette, tuba, percussions, xylophone, glockenspiel, célesta et des cordes.

Concerto en Fa

Pour cette commande du New York Symphony Society, réalisée sur la recommandation de Walter Damrusch, Gershwin ne cache pas « son désir de composer une œuvre de musique pure ». Sous la forme traditionnelle du concerto en un style néo-classique, résolument entre deux eaux, entre jazz et écriture classique, l’ouvrage est donné le 3 Décembre 1925.

Porgy & Bess

Pour le grand écrivain cubain Alejo Carpentier, c’est « une œuvre unique dans le théâtre lyrique moderne, une sorte d’opéra national nord-américain », qui trouvera d’ailleurs en 1959 une traduction cinématographique (trop hiératique d’ailleurs) dans le film éponyme d’Otto Preminger, avec Sidney Poitier, Dorothy Dandridge et Sammy Davis Jr (tous doublés par des chanteurs lyriques) sous la direction musicale d’André Previn. Comme le souligne Alex Ross, avec cet opéra, Gershwin parvient à concilier les principes de la musique écrite occidentale avec l’improvisation inhérente à la tradition afro-américaine. Il n’en reste pas moins que Gershwin pensait qu’un opéra ne pouvait être entièrement jazz, parce que le jazz tel qu’il le percevait selon les codes blancs de son époque, n’était pas gratifiant pour la voix ; selon lui, le jazz correspondait mieux à la danse et au rythme ; les chanteurs noirs de la distribution se montreront néanmoins satisfaits de la partition qui leur est offerte. Et Ella Fitzgerald et louis Armstrong feront la démonstration éclatante de son erreur de jugement.

C’est parce qu’il admirait la dimension sociale de la nouvelle d’Edwin DuBose Heyward (que ce dernier avait adapté en pièce de théâtre), que Gershwin, parfaitement conscient du racisme de la société blanche, veut en faire le sujet d’un opéra. Ira Gershwin, sur le livret de DuBose Heyward, prendra en charge les lyrics au cours de vingt mois de travail.

La partition de Porgy & Bess invite à une grande liberté d’interprétation, ce qui explique le succès que rencontreront les relectures données par des jazzmen. Ceci-dit, en 1935, l’ouvrage dont il est difficile de définir clairement le genre auquel il appartient, ne reçoit pas un accueil délirant à l’Alvin Theatre de New York. A l’instar de Duke Ellington qui trouve qu’il s’agit d’une pièce touchante mais qui n’utilise pas le langage musical des noirs, les intellectuels de la communauté afro -américaine se montreront prudents, voire rétifs, dans leurs commentaires.

Teca CALAZANS / Philippe LESAGE

© 2021 Frémeaux & Associés

Bibliographie :

Franck Médioni : George Gershwin (Folio Biographies ; 2014). Nous avons puisé nombre d’informations et de citations dans cette biographie réussie.

George Gershwin,

from Broadway to the Met

The secret of his art: the in-between

Composers are rarely tender towards their counterparts, as evidenced by this statement attributed to Virgil Thomson, an American critic and composer today quite forgotten: “George Gershwin is not a very serious composer. He does not even know what an opera is.” A severe judgment, but he immediately continued by saying,“And yet Porgy & Bess is an opera, and it has power and vigour.” It showed his amazement. His judgment noted the contrast there was in Gershwin’s music, somewhere between incompetence, ignorance and unexpected artistic results, a contrast that would follow Gershwin throughout his life. But didn’t the secret of his artistry lie precisely in its ambivalence, in that singularity of an indefinable style huddled between ‘popular’ and ‘serious’ music?

This anthology attempts an illustration of that “in-between”. In the present set you can hear jazz musicians playing versions of American songs alongside other works – qualified as “erudite” – performed by artists in the classical music sphere. The cornerstone justifying the term “ambivalence” is the opera Porgy & Bess which, in readings performed by Louis Armstrong with Ella Fitzgerald, or more so with Miles Davis and Gil Evans, represents the enhancement of an operatic work without betraying its spirit.

While Gershwin remains the precursor of the emergent popular music of 1920s America, it hasn’t prevented negative notions continuing to surface right up to the present. Take Renaud Machart for example. As a music critic for Le Monde, a producer for France Musique, and the author of biographies of Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim, Machart wrote: “Despite his melodic and harmonic genius, he (Gershwin) didn’t possess the technical know-how necessary to write serious pieces.” In 1998, Jacques Drillon, then music critic for Le Nouvel Observateur, added: “Porgy & Bess, his 1935 opera, is a load of rubbish. Like everything George Gershwin wrote. Authentically counterfeit.” The self-taught Gershwin was lucid enough to not take such comments as an insult, while he constantly sought advice, if not lessons, from masters like Stravinsky or Ravel. He was neither boastful nor a brag when he went so far as to declare, “I have the modest pretension of contributing to the making of the Great American Songbook.” There were some who corroborated that statement, like Marin Aslop (“If you look at Porgy & Bess, you can see that Gershwin was deploying his composing into all possible forms”); Leonard Bernstein said he could recognise Gershwin “from the very first bar. The voice of a genius.” And let’s not forget Schoenberg: “That Gershwin was an innovator is obvious. What he took from rhythm, harmony and melody constitutes not only a style; it is something fundamentally different from the mannerisms of many so-called ‘serious’ composers.”

Artistic conception

The basic idea behind this anthology was to achieve a variation on Porgy & Bess, the work inspired by the play we owe to Edwin DuBose Heyward, a writer from South Carolina. Not only because it is the last major Gershwin work, and has also been the subject of pure operatic versions (featuring Leontyne Price, among others) and some thrilling new readings, but also because this masterpiece of American opera – one impregnated with jazz, folk music and European influences – hadn’t been performed at New York’s Metropolitan Opera for decades, an anomaly that was rectified in February 2020 thanks to a James Robinson production, with David Robertson conducting and an entirely Afro-American cast, as George and Ira Gershwin had wished it to be.

But before we go back to Porgy & Bess, let us retrace George Gershwin’s path here so as to understand how he came to move from Broadway and musicals to Carnegie Hall and “The Met”. The pages that Alex Ross devotes to him in his book The Rest is Noise make for a wonderful synthesis of the gestation of the composer’s art. Gershwin was born on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, which was rife with a crossbred culture that mixed Russians and others from central Europe with the Yiddish and Blacks born in America. As a teenager, he was saved from the bad influences on the streets by his piano lessons, and as an adult he was the man inside whom the most contrary trends of the moment succeeded in a harmonious fusion: the characteristic energy proper to New York, the songs of Tin Pan Alley, and the ragtime music that oozed from the city’s bars. Gershwin was a Jew of Russian origin who saw himself as a deeply integrated and secular American, and he was one of the rare white musicians of his era to recognise jazz as a major art-form. He loved Art Tatum and Bessie Smith, and he was one of ragtime’s children, fascinated by Scott Joplin, Eubie Blake and James P. Johnson. As Alex Ross points out: “Falling between two stools was in fact the essence of Gershwin’s genius. He led at all times a double-life: as music-theatre professional and concert composer, as highbrow artist and lowbrow entertainer, as all-American kid and white immigrants’ son, as white man and ‘white Negro’.”

Broadway

It was on Broadway that the talent of George Gershwin came to bloom. His success was such that, in a single year, six of his musicals were billed in Broadway theatres. From the first “musical” La-La-Lucille (1919, book by Fred Jackson, lyrics by Buddy DeSylva and Irving Caesar) to Let’ Em Eat Cake (1933), via Oh! Lady Be Good (1924), Oh, Kay! (1926) or Girl Crazy (1930), musicals would provide songs that the greatest voices (and the best jazz soloists) would perform. In 1924 Ira Gershwin wrote the lyrics for Oh! Lady Be Good and became George’s permanent partner. Ira was a portly character whose personality was far distant from that of his energetic younger brother. A placid man who loved to read, he didn’t lack humour and always gave George good advice. The brothers stayed a few months in Hollywood, writing the songs for Shall We Dance, in which their friend Fred Astaire appeared (its memorable titles were They All Laughed and They Can’t Take That Away From Me). This large share of the repertoire, which went into the Great American Songbook (Fascinating Rhythm, Lady Be Good, But Not For Me, Love Is Here To Stay, I’ve Got A Crush On You, Nice Work If You Can Get It, to quote only a few of the titles) is indispensable in evaluating the genius of a composer who, nevertheless, felt an imperious desire to venture into the territory of so-called “serious” music.

Rhapsody In Blue

At the age of merely 25, George Gershwin chose Rhapsody In Blue to insinuate himself into the world of classical music. His reputation in that period was confidential, but in Paul Whiteman he found a man ready to commission him to write a “classical” score, a kind of concerto that had jazz colours. It would be first performed at a well-to-do soirée (in the presence of, among others, Rachmaninov himself, Leopold Stokowski and Jascha Heifetz) that was christened An Experiment In Modern Music.

Rhapsody In Blue is a piece written as a free-form rhapsody in one movement. Gershwin was its composer, and its orchestration was by Ferdinand “Ferde” Grofé. “It is not program music,” explained Gershwin, “but Impressionist music. I have tried to express our way of life, the tempo of our everyday existence with its pace, chaos and vitality. I haven’t attempted to translate precise paintings into sounds.” He was referring to James Whistler’s Impressionist works, and his brother Ira’s advice to include the words “In Blue” in the title of the piece. Bernstein commented: “The themes are extraordinary but the Rhapsody is not a real composition in the sense that whatever happens in it must seem inevitable.” It’s true that the work is more of a collage that combines jazz (to the anger of purists) and orchestral classical music (to the anger of “serious music” lovers). Even so, the concert that took place at New York’s Aeolian Theatre on February 12, 1924, was given a delirious welcome. There’s no doubt that the strange glissando suggested by clarinetist Ross Grosman played its part. The composition was written in 18 days, for two pianos, and there were 33 musicians onstage. To put the Rhapsody into some perspective, we might recall here that by 1921 Varèse had finished composing his Amériques.

An American in Paris

During his stay at the Hotel Majestic in Paris in 1928, Gershwin conceived the first draft of An American in Paris, a piece whose structure was more ambitious and better constructed than Rhapsody In Blue. Its writing remains cast in the spirit of ragtime – the swing style was born later – and this time Gershwin took charge of both its composition and orchestration, stating that this rhapsodic ballet “constitutes the most modern piece of music I have attempted to compose.”

The work was first given at Carnegie Hall on December 13, 1928, (some established critics referred to “innocent and annoying babbling”) and it was first recorded in 1929 (for RCA) under conductor Nathanaël Shilkret. In 1951, Vicente Minelli directed a film with Gene Kelly, Leslie Caron and Georges Guétary that would make the piece definitively famous.

For this three-part ballet in a single movement, a delightfully carefree piece whose pulse underscores the deep movement of the work, the orchestration (without a piano) called for three saxophones, four Parisian taxi horns of different sounds, flute, oboe, English horn, clarinets, bassoons, French horn, trumpets, a tuba, percussion, xylophone, glockenspiel, celesta and strings.

Concerto in F

For this commission from the New York Symphony Society, written on the recommendation of Walter Damrusch, Gershwin made no secret of his “desire to compose a work of pure music.” Written according to the traditional concerto form in the neoclassical style, and placed resolutely between the two stools of jazz and classical music, the work was first performed on December 3, 1925.

Porgy & Bess

According to the great Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier, Porgy & Bess is “a unique work in modern operatic theatre, a sort of national North-American opera.” Incidentally, it was translated onto celluloid in 1959 by Otto Preminger as the eponymous (if too highly stylised) film that stars Sidney Poitier, Dorothy Dandridge and Sammy Davis Jr., all of whose screen voices were dubbed by genuine opera singers, accompanied by an orchestra under conductor André Previn. As Alex Ross has written, with this opera Gershwin succeeded in reconciling the principles of western written music with the improvisations inherent in the Afro-American tradition. This didn’t alter the fact that Gershwin believed an opera could not be entirely jazz, since the latter, in his perception of it (according to the white codes of the period), was not gratifying for voices: jazz, in Gershwin’s view, was better suited to dancers and rhythm. Even so, the black dancers in the cast showed their satisfaction with the score they were given. As for Ella Fitzgerald, she and Louis Armstrong would provide a brilliant demonstration of Gershwin’s error of judgment.

George Gershwin admired the social dimension of DuBose Heyward’s novel (which the latter had adapted into a play), and he was well aware of the racism prevalent in white society; hence his desire to turn it into an opera. Ira Gershwin, working from Hayward’s libretto, took charge of the lyrics in the course of the next twenty months.

The score left itself open to great freedom of interpretation, which explains the success of the numerous readings of the score by jazz musicians. In 1935, however, the work (it is difficult to give a clear definition of the genre to which it belongs) received a welcome at the Alvin Theatre in New York that was hardly over-enthusiastic. Agreeing with Duke Ellington, who found the piece moving but made no use of the musical language of black people, intellectuals in the Afro-American community showed themselves prudent, if not hostile, in their expressed opinions.

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the French text of

Teca CALAZANS / Philippe LESAGE

© 2021 Frémeaux & Associés

Bibliography:

Franck Médioni, “George Gershwin”, Folio, publ. 2014. An accomplished biography and the source of much information and quotes.

George Gershwin, from Broadway to the Met - DISCOGRAPHIE

CD1

1) I Loves You Porgy (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward / George Gershwin) Nina Simone (voc, piano) – LP Little Girl Blue 1958 Bethlehem BLP - 6028 4’09

2) But Not For Me (George et Ira Gershwin) Erroll Garner (piano), Al Hall (b), Gordon « Specs » Powell (dr)

Le piano magique – CBS 52 065 - 1956 3’38

3) My Man’s Gone Now (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward, George Gershwin), Bill Evans (piano), Scott LaFaro (bass), Paul Motian (drums) – Riverside 376 - LP Bill Evans Trio « Sunday At The Village Vanguard » – 25 juin 1961 6’24

4) Nice Work If You Can Get It (George et Ira Gershwin), Sarah Vaughan, (voc), acc by Jimmy Jones and his orchestra, feat Miles Davis (tp) – Columbia CL 6133 - 1950 2’38

5) Summertime (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward / George Gershwin) Duke Ellington (p), Aaron Bell, (bass), Sam Woodyard (drums) – LP Piano In The Foreground – Columbia CL 2029/ 1961 3’50

6) The Man I Love (George et Ira Gershwin) Billie Holiday (voc), Buck Clayton, Harry « Sweet » Edison (tp) Earle Warren (as), Lester Young (ts), Jack Washington (alto et baryton sax), Joe Sullivan (p), Freddie Greene (g), Walter Page (b), Joe Jones (dr) T8 rpm – Vocalion 5377 - 13 décembre 1939 3’03

7) It Ain’t Necessarily So (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward /G.Gershwin) Aretha Franklin, (voc) with Ray Bryant Combo – Columbia CS 8412-19 2’51

8) I Loves You Porgy (George Gershwin & DuBose Heyward/Gershwin) Billy Holiday (Voc) & Bobby Tucker and his Trio. (Bobby Tucker: piano ; Mundell Lowe: guitar ; Denzil Best: Dr. Vocal group) 78 rpm – Decca 24683 - décembre 1948. 2’58

9) The Man I Love (George et Ira Gershwin) Don Byas (ts), Maurice Vander, Jean-Pierre Sasson (g), Jacques Medvedko (b), Benny Bennett (dr) – LP Blue Star 6802 - 19 avril 1951 2’44

10) Embraceable You (George et Ira Gershwin) Chet Baker (voc & tp), David Wheat (g), Ross Savakuss (b) – Pacific Jazz - 9 décembre 1957 2’09

11) They all Laughed (George et Ira Gershwin) Chet Baker (voc, tp), David Wheat (g), Ross Savakuss (b) – Pacific Jazz - 9 decembre 1957 2’11

12) How Long has This Been Going On (Ira & George Gershwin) Chet Baker (tp, voc), Kenny Drew (p), George Morrow (b), Philly Joe Jones (dr) - Riverside RLP 1120 – LP Chet Baker Sings - Août 1958 4’10

13) Summertime (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward/ George Gershwin) Lonnie Johnson (voc,g) LP Losing Game, Bluesville - 28 décembre 1960 3’28

14) It Ain’t Necessarily So (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward, George Gershwin) Miles Davis (tp), orchestra under the direction of Gil Evans. Les musiciens : Ernie Royal, Louis Mucci, John Coles et Bernie Glow (tp), Jimmy Cleveland, Joseph Bennett, Dick Hixon, Frank Rehak (tb), Julian Adderley, Danny Banks (sax), Willie Ruff, Julius Watkins, Gunther Schuller (french horn), Phil Bodner, Romeo Penque (fl), Bill Barber (Tuba), Paul Chambers (b), Philly Joe Jones (dr) – CBS 32188 du 29 juillet au 18 août 1958 4’25

15) My Man’s Gone Now (idem 14) 6’15

16) Gone, Gone, Gone (idem 14) 2’03

17) I Loves You Porgy (idem 14) 4’02

18) Bess, You Is My Woman Now (idem 14) 5’14

19) Gone (idem 14) 3’40

20) Summertime (idem 14) 3’18

21) There’s Is A Boat That’s Leaving Soon For New York (idem 14) 3’26

CD2

Porgy & Bess. Verve records 0383, 1958, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, orchestra conducted by Russell Garcia, music by George Gershwin, lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin - Frank Reah (tp), Milt Benhardt (tb), Vincent DeRosa (French horn), Bill Miller, Paul Smith (p), Tony Rizzi (g), Joe Mondragon (b), Alvin Stoller (dr)

1) Summertime 4’58

2) I Wants To Stay Here 3’38

3) It Ain’t Necessarily So 6’34

4) My Man’s Gone Now 4’02

5) I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’ 3’52

6) Bess, You Is My Woman Now 5’28

7) A Woman Is A Sometime Thing 4’47

8) Oh, Doctor Jesus 2’00

9) Buzzard Song 2’58

10) What You Want Wid Bass ? 1’59

11) There’s A Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon For New York 4’54

12) O Bess, Oh Where’ My Bess? 2’36

13) Oh Lawd, I’m On My Way 2’56

Oscar Peterson Trio plays Porgy & Bess - Verve V6 -8340-1959, Oscar Peterson (p), Ray Brown (b), Ed Thigpen (dr)

14) I Got Plenty O’Nuttin’ (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward/ George Gershwin) 6’23

15) I Wants To Stay here (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward/ George Gershwin) 6’20

16) There’s a Boat Dat’s Leavin’ soon For New York (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward/ George Gershwin) 7’11

17) Bess, You Is My Woman Now (Ira Gershwin, DuBose Heyward/ George Gershwin) 3’30

CD 3

1) Un Américain à Paris (George Gershwin)

The Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra, directed by Felix Slatkin,

Capitol Recors P-8343, 1956 17’58

2) Concerto en Fa – Allegro (George Gershwin) 13’08

3) Concerto en Fa – Andante (George Gershwin) 13’02

4) Concerto en Fa – Allegro (George Gershwin)

Concerto pour piano et orchestre ; Daniel Wayenberg (piano) Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, direction Georges Prêtre

Enregistré Salle Wagram, 1960/ EMI CVL 504 7’00

5) Rhapsody In Blue (George Gershwin)

Daniel Wayenberg (piano), Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, direction George Prêtre.

30 novembre au 5 décembre 1960

EMI CVL 504 16’17