- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

24th OF APRIL 1962

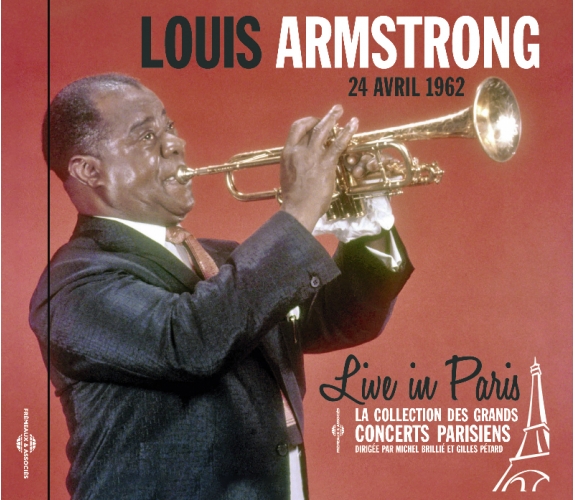

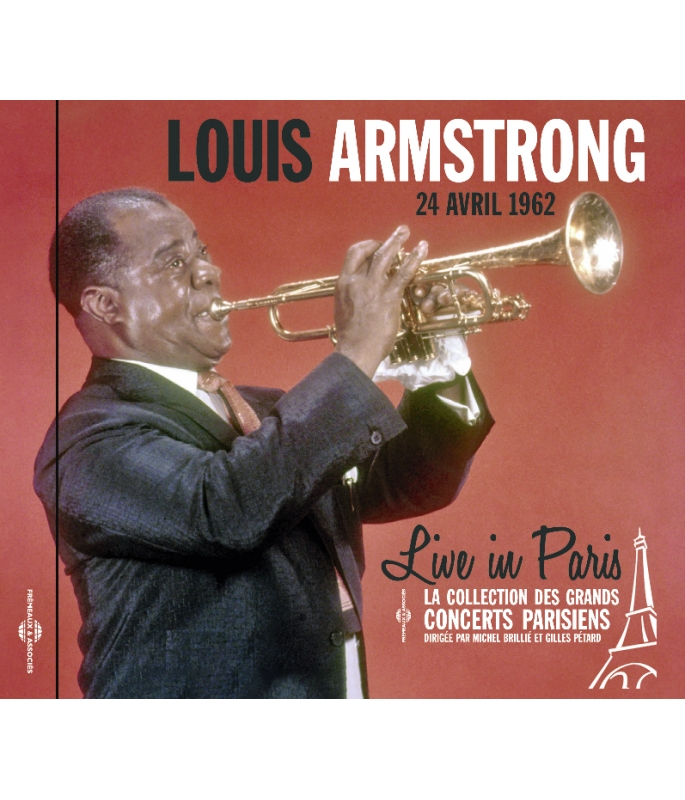

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

Ref.: FA5612

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 16 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

24th OF APRIL 1962

More than a major figure of the 20th century, Louis Armstrong is an incandescent jazz icon, an architect and pioneering founder of jazz music for half a century. One of the greatest trumpeters, Louis lived in Montmartre for a few years before the war, and he felt quite at home. Paris was a city he adored, and the city loved him back. This exceptional concert shows “Pops” at the summit; radiating good humour, he has the audience eating out of his hand. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The Live in Paris collection by Michel Brillié allows listeners to hear previously-unreleased recordings (made at concerts and private- or radio-sessions) by the great 20th stars in jazz, rock & roll and song. These “live” takes, and the artists’ rapport with their audiences, gives these performances an additional soul and sensibility in counterpoint to the rigorous demands of studio recordings. Particular care was taken when restoring the sound of these tapes in order to meet CD standards while preserving the original colours of the period. Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : GILLES PÉTARD ET MICHEL BRILLIÉ

DROITS : BODY & SOUL LICENCIE A FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES.

WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH • (BACK HOME AGAIN IN) INDIANA • A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON • MY BUCKET’S GOT A HOLE IN IT • TIGER RAG • NOW YOU HAS JAZZ • HIGH SOCIETY • OLE MISS RAG • WHEN I GROW TOO OLD TO DREAM • TINROOF BLUES • YELLOW DOG BLUES • WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHING IN • STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE • NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN • BLUEBERRY HILL • THE FAITHFUL HUSSAR • ST. LOUIS BLUES [FEAT. JEWEL BROWN] • AFTER YOU’VE GONE • MACK THE KNIFE.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1When It's Sleepy Down SouthLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaC. Muse00:03:171962

-

2(Back Home Again In) IndianaLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaJ. F. Hanley00:04:221962

-

3A Kiss to Build a Dream OnLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaH. Ruby00:04:271962

-

4My Bucket's Got a Hole In ItLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaWilliams Hank00:03:161962

-

5Tiger RagLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaNick Larocca00:01:261962

-

6Now You Has JazzLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaC. Porter00:06:511962

-

7High SocietyLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaC. Porter00:03:031962

-

8Ole Miss RagLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny Barcelona00:03:481962

-

9When I Grow Too Old To DreamLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaOscar Hammerstein II00:04:171962

-

10Tin Roof BluesLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaW. Melrose00:05:181962

-

11Yellow Dog BluesLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny Barcelona00:03:001962

-

12When the Saints Go Marching inLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaTraditionnel00:03:331962

-

13Struttin' With Some BarbecueLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaLil Armstrong00:05:511962

-

14Nobody Knows The Trouble I've SeenLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaTraditionnel00:03:131962

-

15Blueberry HillLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaVincent Rose00:03:271962

-

16The Faithfull HussarLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaHeinrich Frantzen00:05:101962

-

17St. Louis BluesLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny Barcelona, J. BrownW. C. Handy00:03:361962

-

18After You've GoneLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaTurner Layton00:03:231962

-

19Mack The KnifeLouis Armstrong, T. Young, Joe Darensbourg, Billy Kyle, Bill Cronk, Danny BarcelonaBertold Brecht00:04:521962

Armtrong Live FA5612

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

24 AVRIL 1962

Live in Paris

La collection des grands concerts parisiens

Dirigée par Michel Brillié et Gilles Pétard

Louis Armstrong

LIVE IN PARIS 24 avril 1962

Par Michel BRILLIÉ

A bientôt, Louis !

Il aura fallu soixante-quatre ans à Paris pour saluer la mémoire de Louis Armstrong, cet homme si attaché à la capitale française. Au départ, 1934, l’année du premier long séjour de Louis en France et à Paris. À l’arrivée, 1998, quand finalement la mairie du 13e arrondissement, encouragée par Frank Ténot, inaugure en son nom une place arborée du quartier Salpêtrière, non loin des studios Polydor où Jacques Canetti dirigea la première séance d’enregistrement française de Satchmo, à la fin de l’année 1934. Frank Ténot d’ailleurs prétendait malicieusement qu’un assistant technicien de cette mémorable séance avait, paraît-il, proposé à Armstrong des pastilles de menthe pour s’éclaircir la voix…

Dire que la relation entre la France et le trompettiste-chanteur est étroite est un understatement. Paris en 34 a dû lui apparaître comme un ‘wonderful world’ en comparaison avec son Amérique natale. C’est en Europe et en France que les critiques de l’époque, Hugues Panassié en tête, donnent au jazz ses lettres de noblesse, par contraste avec l’attitude américaine qui considère cette musique comme un divertissement bon pour la danse. Dès le choc des premiers concerts des 9 et 10 novembre 1934 à la salle Pleyel, les lieux où se produira Armstrong seront bondés d’un public exubérant. Quand en septembre 1934, Louis s’installe avec Alpha, sa volcanique épouse, près de la place Pigalle dans l’appartement de la rue de la Tour d’Auvergne que lui a dégotté Canetti, il trouve rapidement ses marques. Il y reste jusqu’en février 1935, adoptant le French way of life avec aisance.

Le matin, les habitants de la rue le voient, coiffé d’une casquette à carreaux, promener son chien ; le soir, aller à la salle Bullard, rue Mansart, pour y faire un peu de culture physique au milieu de boxeurs américains de passage. Plus tard, Louis prend un verre au Bourdon, le café rendez-vous des jazzmen du moment. La fin de soirée le retrouve à la Villa d’Este ou Chez Bricktop’s, le club de Pigalle de la chanteuse Ada Smith. Y jouent Sidney Bechet, Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Django Reinhardt… On l’imagine aisément faisant le bœuf avec le guitariste manouche : « Sans échanger un mot, les deux hommes se jaugèrent. Ayant gonflé ses joues en caoutchouc, Louis lance une note que Django saisit au vol et en avant pour trois quarts d’heure de pure jubilation. Ils s’envoyaient des vannes par notes interposées. C’était à celui qui lancerait le meilleur calembour musical. Trompette et guitare rivalisaient d’humour. Quand ce fut fini, l’heureux créateur d’un monde merveilleux embrassa sur le front le gamin vif-argent et quitta le cabaret sur un tonitruant éclat de rire. » (Alexis Salatko, Folles de Django, roman, Editions Robert Laffont, 2013). À Paris, pour Louis, le jazz est partout dans la rue. Alix Combelle raconte à Hugues Panassié que, pendant l’un de ses séjours parisiens, Louis et lui remontaient la rue Pigalle à une heure avancée de la nuit, quand passa une voiture à cheval. Les sabots de l’animal sonnaient distinctement sur le pavé et Louis, sur ce rythme imprévu, se mit aussitôt à improviser en chantant, au grand émerveillement de son compagnon.

Cette belle liaison entre Paris et Armstrong va se prolonger comme une idylle sans nuage tout au long du vingtième siècle. Louis adore les restaurants et les bistrots de Pigalle, et ses admirateurs, anonymes ou célèbres, le vénèrent : « Sa trompette parle une sorte de terrible langage humain, monte en zigzags, en rétablissements, en glissades, et arrive, sans se tuer, au haut du plus haut gratte-ciel, où elle crache un jet de sang pourpre. Armstrong c’est l’ange de Jéricho, le soldat de l’Apocalypse, le point parfait où s’épousent la prière céleste du Nègre et son érotisme infernal. » (Jean Cocteau, cité par Michel Boujut, Louis Armstrong, Editions Plume, 1998).

Après l’interruption de la guerre, 1948 voit le retour du musicien sur le sol français. En mars, salle Pleyel, il donne deux concerts archi-bourrés où les organisateurs refoulent plusieurs milliers de personnes. Armstrong y arrive sous la protection de quinze agents de police, pour déjouer une menace d’agression anonyme. À la sortie, raconte Hugues Panassié, « une telle foule attendait Louis Armstrong que Michel de Bry, pour soustraire Louis à la ruée de ses admirateurs, le fit monter dans le car de police qui stationnait devant Pleyel, lequel ‘panier à salade’ démarra aussitôt ! » (Hugues Panassié, Louis Armstrong, Nouvelles Editions Latines, 1969). C’est en grande vedette qu’il apparaît ensuite pendant l’été au festival de Nice ; et c’est bien un hôte de marque que le président de la République Vincent Auriol récompense par l’intermédiaire d’Yves Montand en lui offrant un magnifique vase de Sèvres.

L’année suivante, Louis rejoint les grands de ce monde, présidents, et autres monarques… Il est sacré « Roi des Zoulous » par une association locale lors de la parade du Mardi Gras à la Nouvelle- Orléans. Leonard Feather, le grand écrivain du jazz, relate la cérémonie : « Le roi avait la figure toute noire avec des grands ronds blancs autour des yeux et de la bouche. Il portait une couronne, une longue perruque noire, une tunique de velours rouge brodée de sequins d’or, une chemise de cellophane jaune et un collant noir avec des hautes chaussures dorées. Il avait un gros cigare et un sceptre d’argent. Sûr, Louis était grotesque, mais c’était l’homme le plus heureux que j’ai vu de ma vie. » (Jazz Hot N°32, avril 1949 – Traduction Boris Vian)

Et voici Louis dans les années cinquante. Le chanteur a entendu « La vie en rose » d’Edith Piaf lors d’une tournée en Belgique, et l’a magistralement adaptée avec sa voix « de gorille et de tourterelle » comme l’écrit Léopold Sédar Senghor, la transformant en succès planétaire. Autre reprise célèbre que Louis va enregistrer à Los Angeles fin septembre 1955, juste avant de s’embarquer pour une nouvelle tournée européenne, et qui sera l’un de ses plus grands best-sellers : « Mack the Knife », de l’Opéra de Quat’ Sous de Bertold Brecht et Kurt Weil. Puis Satchmo traverse le continent américain et l’Atlantique, emportant avec lui comme à l’accoutumée vingt-quatre valises, dans lesquelles on trouve deux magnétophones, un transistor, une trousse à médicaments avec tout ce qu’il faut pour soigner maux de dents, problèmes oculaires, lèvres, laxatifs, etc.

A Paris, du 17 novembre au 6 décembre 1955, pendant trois semaines consécutives, il passe en vedette à l’Olympia, avec le fantaisiste Jean Constantin au programme. Il est « éblouissant », selon Hugues Panassié : plus de trente représentations, avec scènes d’enthousiasme de ses admirateurs que la presse qualifiera d’« émeutes ». Pendant ce séjour, Daniel Filipacchi réalise avec Louis une séance de photos en studio qui paraît dans le numéro de novembre 1955 de Jazz Magazine. Daniel se souvient de ce passage parisien de Satchmo : « C’était un type tout à fait sympa et adorable… On avait fait des photos avec lui et Mezz (Mezzrow). C’était à l’époque où il était maigre… Relativement maigre. Il avait perdu quelques dizaines de kilos… Qu’il reprenait immédiatement. On était allés au restaurant chez Allard… Il était un peu poursuivi, il avait des fans qui lui couraient après. Comme il était très gentil, aimable et complaisant, j’essayais de lui éviter le pire. Je l’ai hébergé quelques jours chez moi, rue de Verneuil… On restait là, on regardait la télé. » Le goût de Louis Armstrong pour la gastronomie française l’amène même parfois à y faire référence pendant ses concerts parisiens : « Cassoulet is waiting ! » s’exclame-t-il à son public ravi. Mais l’homme qui a pour plat préféré les red beans and rice, les haricots rouges avec du riz, le plat de base des noirs des États du sud, n’oublie pas ses racines, même dans la capitale de la haute cuisine : une photo le représente à Pigalle en compagnie de Gabrielle Haynes, la fondatrice, avec son mari Leroy, du mythique restaurant Gabby & Haynes, la première table en France à proposer des plats de cuisine traditionnelle du vieux sud des États -Unis. Le grand Satchmo est gourmand - il est aussi généreux. A Pleyel, lors d’un concert qui se finit à point d’heure, la concierge du lieu se désespère devant lui d’avoir loupé le dernier métro : Louis sort alors un gros billet de son portefeuille et lui tend. Quelques années plus tard, il repasse dans la même salle et retrouve la même concierge. Il éclate de rire à sa vue : « Ha ha ha…No metro for you tonight, taxi ! »

Plus la décennie avance, plus l’audience d’Armstrong s’accroît et s’internationalise. Il sillonne le monde réunissant des foules énormes : 25.000 personnes au Festival de Newport pour son anniversaire, 50.000 à Accra au Ghana lors de sa grande tournée africaine, 100.000 à Kingston en Jamaïque… Armstrong est devenu de fait l’ambassadeur itinérant de la musique noire, « le titan noir du cri » (Le Corbusier, Quand les cathédrales étaient blanches, Editions Bartillat, 2012).

Ce globe-trotter du jazz n’en oublie pas pour autant Paris et ses terrasses de bistrots préférés : Louis y repasse quelques semaines en décembre 1960, d’abord pour y donner plusieurs concerts, et pour tourner dans le film Paris Blues de Martin Ritt en compagnie de Paul Newman, Sidney Poitier et Duke Ellington. Herman Leonard, le photographe du jazz au XXe siècle avec William Claxton, fixe Louis, Duke et son orchestre au grand complet aux fenêtres du très classieux hôtel de la Trémoille dans le quartier des Champs-Elysées. Le film est devenu avec l’âge un hommage mélancolique au Paris du début des sixties ; il est à revoir, ne serait-ce que pour la scène du début où Wild Man Moore, le musicien joué par Satchmo, improvise depuis son compartiment de wagon-lit pour ses fans venus l’accueillir sur le quai de la gare Saint Lazare.

Films, concerts, voyages… tournées. Armstrong travaille trop. Sa voix « de râpe » (Vian) fatigue un peu. Mais il est là, toujours vaillant. Comme lors de son retour à l’Olympia, en avril 1962. Paris lui appartient, la presse lui est toute dévouée : « Armstrong, bravo et merci » (L’Aurore) ; « Les jeunes découvrent l’arbre de vie ; ce visage où s’inscrivent toutes les peines et les joies d’une race, … / … ces notes d’or qu’Armstrong semble fixer dans le ciel » (Michel Perrin, Les Nouvelles littéraires). Et les critiques redoutés sont (presque) au diapason : « Le talent d’Armstrong nous fait oublier la qualité des solos de ses musiciens. Armstrong était en pleine forme. Outre ses nombreux vocaux toujours pleins d’humour, d’intérêt et de swing, ses parties de trompette étaient remarquables. A bientôt, Louis ! » (Jazz Magazine, juin 1962).

C’est vrai, on lui reproche aussi de ne pas changer d’un iota son répertoire, de ne jouer que ses morceaux ultra-célèbres. Déjà son premier manager, Johnny Collins, lui en avait fait la remarque dès le début de leur association. Cela avait provoqué une colère noire de Satchmo : « Ecoute, espèce d’enfoiré ! Peut-être que tu es mon manager et un gros qui se la pète avec tout le fric des concerts que tu bookes, mais quand je monte sur scène avec mon instrument et que je suis dans la merde, c’est pas toi qui vas me sauver. » (Terry Teachout, Pops : the wonderful world of Louis Armstrong, JR Books Ltd, 2009). Sur scène, Louis est le magicien qui « tire des paillettes d’or de la mélodie la plus banale » (Jacques Réda, Anthologie des musiciens de Jazz, Editions Stock musique). Amuseur ou génie, synthèse du sublime et du bouffon, Grock du Jazz, qu’importe… Pour le coup de chapeau final, place à Boris : « Armstrong, il peut jouer ‘La Marseillaise’, au tuba, demain matin… se déculotter devant l’Arc de Triomphe ; scier la colonne Vendôme avec une fourchette bleue et manger des huîtres tout en courant le long des Tuileries, il aura quand même gravé 300 faces (au moins) inoubliables. » (Boris Vian, En Verve, Editions Pierre Horay, 1970.) © FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

LIVE IN PARIS April 24, 1962

By Michel BRILLIÉ

See you soon, Louis…

It took sixty-four years for the city of Paris to honor the memory of Louis Armstong, the musician and the man so fond of the French capital. The story started in 1934 when Louis Armstrong arrived in Paris for the first time. It ended in 1998 as a tree-shaded square was named after him in a ceremony presided by the mayor of the 13th arrondissement (district) of the city, strongly supported by French jazz personality Frank Ténot. The Place Louis Armstrong is a step away from Polydor Records studios where French producer Jacques Canetti directed the first session of Satchmo and his band on the French soil, at the end of 1934. Ténot asserted mischievously that a reliable witness of that session had seen an assistant offer Armstrong lozenges to clear his throat…

To say that the relationship between France and the singer-musician was close is an understatement. In ’34, Paris was definitely a wonderful world to his eyes, compared to his native land. For it is in Europe and France that critics of the time, such as Hugues Panassié, gave jazz its noble music status, contrary to the common American attitude that considered it as just an entertaining way to dance. Right from the very first concerts in 1934 at the Salle Pleyel in Paris, Armstrong played to concert halls filled to capacity with enthusiastic audiences. When in September 1934, Louis and his tornado of a wife Alpha settled down in a central Paris apartment provided by Canetti, he quickly found his way. He remained in town until February ’35, completely adopting the French way of life.

Locals could spot him in the morning, walking his dog wearing a checkered cap. In the evening, they could see him going for a workout at the Salle Bullard, a gym on rue Mansart, where he would watch American boxers train. Louis may have then had a drink at the Bourdon, the meeting place of jazzmen in town. At the end of the night, the musician would hit the Villa d’Este or Chez Bricktop’s, singer Ada Smith’s club in Pigalle. There he may have run into Sidney Bechet, Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, or Django Reinhardt… We can easily imagine him jamming with the gipsy guitar player: “Without a word, the two men size each other up. Blowing his rubber cheeks, Louis projects a note that Django catches in mid-air and they’re off for forty-five minutes of pure joy. They would tease each other by means of music notes. It was a contest for the best musical pun, a humorous rivalry between the trumpet and the guitar. When it was over, the blessed creator of a wonderful world would kiss the forehead of the quicksilver kid and leave the club with an enormous laughter.” (Folles de Django, a novel, by Alexis Salatko, Editions Robert Laffont, 2013). For Louis, jazz was everywhere to be found in Paris. French musician Alix Combelle reminisces with Hugues Panassié that one night, while Louis was in town, Armstrong and he were going up the rue Pigalle at some late hour, when a horse-drawn cart passed by. The sound of the hoofs of the animal on the cobblestones immediately inspired Louis to improvise a song on this unexpected tempo, to the delight of his companion.

This love affair between Louis and Paris remained unclouded throughout the twentieth century. Louis loved the restaurants and the bistros in Pigalle, and his unknown or illustrious Parisian admirers worshipped him: “His trumpet lets out some kind of furious human language, going up in zig zag, recovering then sliding to end up at the top of the tallest skyscraper, where it spits out some crimson blood stream. Armstrong is the Angel of Jericho, the Soldier of the Apocalypse, the perfect mating point for the Negro heavenly prayer and its infernal eroticism.” (Jean Cocteau, quoted in Louis Armstrong, by Michel Boujut, Editions Plume, 1998)

After World War II, the musician returned to France in 1948. In March, Louis performed at the Salle Pleyel in Paris for two sold-out concerts, where several thousand people were turned down. Armstrong arrived there under the protection of fifteen policemen, as he had received threats. After the show, as Hugues Panasssié recalls in his book Louis Armstrong (Nouvelles Editions Latines, 1969), “there was such a crowd waiting for him that, to protect Louis from the fervor of his fans, Michel de Bry had to whisk him in a police van which was parked in front of the Salle Pleyel, and the paddy wagon took off immediately!” Armstrong then appeared at the following summer Nice Festival. At this time, he is received almost like royalty as actor Yves Montand presents him with a magnificent vase from the Manufacture de Sèvres, on behalf of President Vincent Auriol.

One year later, Louis ‘officially’ joins the mighty ones of this world, presidents and monarchs alike… Satchmo is crowned “King of the Zulus” by a prominent social club during New Orleans Mardi Gras Parade. Leonard Feather is on the scene and relates the March 1949 event: “The king had blackface makeup except for an area around his eyes and lips which were painted white; he wore a red-feathered cardboard crown, a long black wig, a red velvet tunic with gold sequins, a grass shirt and black-dyed long underwear with gold shoes. He sported a big fat cigar and a golden scepter. Sure, Louis was a little farcical, but this was the happiest man I ever saw in my life.” (Jazz Hot Magazine N°32, April 1949 – French Translation by Boris Vian)

And on we move to the fifties. While touring Belgium, the singer hears Edith Piaf’s ‘La vie en rose’ and records his own striking rendition with his “gorilla and turtledove” voice, as Leopold Sédar Senghor writes, turning the song into a world-wide hit. At the end of September 1955, Louis also records another reprise in Los Angeles, just before embarking for a new European tour: it’s ‘Mack the Knife’, from Bertold Brecht and Kurt Weil’s Three Penny Opera, which will become a standard in his repertoire. Then Satchmo travels across America and the Atlantic Ocean to reach Europe one more time. As usual, he brings along twenty-four suitcases filled with two tape recorders, one transistor radio, and a medicine case complete with everything needed to cure tooth-ache, eye problems, and even laxatives.

In Paris, during three whole weeks, from November 17 to December 6, 1955, he stars at the Olympia Theater, along with French comic singer Jean Constantin. He is “dazzling” in the words of Hugues Panassié. For more than thirty appearances, there are deliriously enthusiastic fans who almost start ‘riots’, as related in the French press. During this stay, photographer and friend Daniel Filipacchi shot a studio photo session included in the November 1955 issue of Jazz Magazine. Daniel remembers this Parisian episode vividly: “He was really a quite lovable and friendly guy… I had shot some pictures of him with Mezz (Mezzrow). At that time he was slim… Well, relatively slim. He had lost a lot of weight that he would regain immediately. We went to Allard restaurant… He was a little bit harassed by eager fans. Since he was such a nice, pleasant and accommodating man, I tried to protect him from the worst. I put him up at my place, on rue de Verneuil, for a few days. We would just stay there watching TV.” Armstrong’s love for French gastronomy even shows during his Parisian concerts, as he sometimes would open the show with a loud gargantuan “Cassoulet is waiting!” roar to his delighted audience. But the man whose favorite dish is the basic southern ‘red beans and rice’ wasn’t forgetting his roots: there is a picture of him in Pigalle next to Gabrielle Haynes, the woman who founded Gabby & Haynes Restaurant with her husband Leroy, the first place to feature a traditional Southern US fare in France. Satchmo is a fine gourmet with a generous mind: on one occasion at the Salle Pleyel, the show ended really late, and the concierge was totally upset to have missed the last metro… So Louis took out a large banknote from his wallet and handed it to her. Several years later, Armstrong was back in the same place for a performance, and there was the same concierge. Louis burst out laughing: «Ha ha ha… No metro for you tonight, taxi! »

As the years grow in number, so does Armstrong’s international audience. He travels intensively throughout the world gathering huge crowds: 25.000 spectators at the Newport Festival on his birthday; 50.000 in Accra, Ghana during his big African tour; 100.000 in Kingston, Jamaica… Armstrong had become the travelling ambassador of black music, “the black shouting titan” (Le Corbusier, Quand les cathédrales étaient blanches, Editions Bartillat, 2012).

In spite of all the acclaim, this world traveler of jazz music does not forget Paris and his favorite sidewalk cafés: Louis is back in town for a few weeks in December 1960. He gives several concerts and shoots some scenes of Martin Ritt’s film Paris Blues, along with Paul Newman, Sidney Poitier and Duke Ellington. Herman Leonard, the jazz photographer of the times (with William Claxton), catches on camera Louis, Duke and his whole band standing at the windows of the posh Hotel de la Trémoille in the Champs-Elysées district. With time, the movie has become a tender tribute to the early sixties in Paris; it’s a pleasure to see again, if only for the opening scene when Louis, as musician Wild Man Moore, improvises from his train window in the Saint Lazare train Station, cheered on by exuberant fans.

Movies, concerts, travels, tours: throughout his life, Louis worked too hard. His ‘grater sounding’ voice (Boris Vian) got tired at times. But in April 1962, he is still bravely standing for his comeback at the Olympia Theater. Paris belongs once again to Armstrong, and so does a devoted press: “Armstrong, bravo and thanks a lot” (L’Aurore); “Young people have found the tree of life; this face that bears all the sorrows and joys of a race; … /… these golden notes that Armstrong seems to shoot in the sky” (Michel Perrin, Les Nouvelles littéraires). And the feared critics (almost) in tune state: “Armstrong’s talent makes us forget the level of ability of his musicians. Armstrong was indeed in great shape. In addition to his vocals parts full of humor, interest and swing, his trumpet solos were outstanding. See you soon, Louis!” (Jazz Magazine, June 1962)

True, his repertoire didn’t change in the slightest from year to year, confined strictly to ultra-famous numbers. His first manager, Johnny Collins, had already made that remark at the start of their association. Satchmo had become absolutely furious: “Listen, cocksucker, you might be my manager and you might be the biggest shit, booking the best business in the world, but when I get on the fucking stage with that horn and get in trouble, you can’t save me! ” (Terry Teachout, Pops: the wonderful world of Louis Armstrong, JR Books Ltd, 2009). On stage, Louis remained a magician that “draws glitters of gold from the most common melody” (Jacques Réda, Anthologie des musiciens de Jazz, Editions Stock musique). Whether an entertainer or a genius, the combination of the sublime and the grotesque, a Grock of Jazz Music, who cares… And to finish, one final tip of the hat from French iconic writer Boris Vian: “Armstrong can play the ‘Marseillaise’ with a tuba tomorrow morning, or pull down his pants under the Arc de Triomphe; or saw off the Colonne Vendôme with a blue fork and eat oysters while running along the Tuileries Gardens, he will remain the man that cut (at least) 300 unforgettable records.” (Boris Vian, En Verve, Editions Pierre Horay, 1970)

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

1. When It’s Sleepy Time Down South (Clarence Muse / Leon René / Otis René) 3’17

2. (Back Home Again in) Indiana (James F. Hanley / Ballard MacDonald ) 4’22

3. A Kiss to Build a Dream On (Harry Ruby / Bert Kalmar / Oscar Hammerstein II) 4’27

4. My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It (Hank Williams) 3’16

5. Tiger Rag (Nick LaRocca / Eddie Edwards / Henry Ragas /Tony Sbarbaro - Harry DaCosta) 1’26

6. Now You Has Jazz (Cole Porter) 6’51

7. High Society (Cole Porter) 3’03

8. Ole Miss Rag (W.C. Handy) 3’48

9. When I Grow Too Old to Dream (Sigmund Romberg / Oscar Hammerstein II) 4’17

10. Tin Roof Blues (Paul Mares / Ben Pollack / Mel Stitzel / George Brunies / Leon Roppolo) 5’18

11. Yellow Dog Blues (W. C. Handy) 3’00

12. When the Saints Go Marching in (Traditional) 3’33

13. Struttin’ With Some Barbecue (Lil Hardin Armstrong / Louis Armstrong / Don Raye) 5’51

14. Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen (Traditional) 3’13

15. Blueberry Hill (Vincent Rose / Larry Stock / Al Lewis) 3’27

16. The Faithful Hussar (Heinrich Frantzen / Louis Armstrong) 5’10

17. St. Louis Blues [feat. Jewel Brown] (W.C. Handy) 3’36

18. After You’ve Gone (Turner Layton / Henry Creamer) 3’23

19. Mack the Knife (Kurt Weill / Marc Blitzstein / Bertolt Brecht) 4’52

Recorded by: Europe N°1 Technical Staff

Recording date

April 24, 1962

Recording place

Olympia Theater, Paris, France

Produced by:

Daniel Filipacchi & Frank Ténot

Personnel

Louis Armstrong (tp, voc)

Trummy Young (tb)

Joe Darensbourg (cl)

Billy Kyle (p)

Bill Cronk (b)

Danny Barcelona (ds)

Jewel Brown (track 17) (voc)

Dedicated to Claude Boquet, Bill Dubois, Jean Claude, Philippe Moch and the gang

La collection Live in Paris :

Collection créée par Gilles Pétard pour Body & Soul

et licenciée à Frémeaux & Associés

Direction artistique et discographie : Michel Brillié, Gilles Pétard

Coordination : Augustin Bondoux

Conception : Patrick Frémeaux, Claude Colombini

Fabrication et distribution : Frémeaux & Associés

Figure majeure du XXe siècle, Louis Armstrong est l’icône incandescente du jazz, dont il fut parmi les pionniers fondateurs et grands architectes pendant un demi-siècle. Le trompettiste, qui avait vécu quelques années dans le Montmartre d’Avant-guerre, se sentait à Paris comme chez lui, se retrouve dans une ville qu’il adorait et qui l’adulait. Un concert exceptionnel dans lequel « Pops », au sommet, irradie de bonne humeur et de maitrise un auditoire conquis.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

More than a major figure of the 20th century, Louis Armstrong is an incandescent jazz icon, an architect and pioneering founder of jazz music for half a century. One of the greatest trumpeters, Louis lived in Montmartre for a few years before the war, and he felt quite at home. Paris was a city he adored, and the city loved him back. This exceptional concert shows “Pops” at the summit; radiating good humour, he has the audience eating out of his hand.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

La collection Live in Paris, dirigée par Michel Brillié, permet de retrouver des enregistrements inédits (concerts, sessions privées ou radiophoniques), des grandes vedettes du jazz, du rock & roll et de la chanson du XXe siècle. Ces prises de son live, et la relation avec le public, apportent un supplément d’âme et une sensibilité en contrepoint de la rigueur appliquée lors des enregistrements studios. Une importance singulière a été apportée à la restauration sonore des bandes, pour convenir aux standards CD tout en conservant la couleur d’époque.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

The Live in Paris collection by Michel Brillié allows listeners to hear previously-unreleased recordings (made at concerts and private- or radio-sessions) by the great 20th stars in jazz, rock & roll and song. These “live” takes, and the artists’ rapport with their audiences, gives these performances an additional soul and sensibility in counterpoint to the rigorous demands of studio recordings. Particular care was taken when restoring the sound of these tapes in order to meet CD standards while preserving the original colours of the period.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

1. When It’s Sleepy Time Down South 3’17

2. (Back Home Again in) Indiana 4’22

3. A Kiss to Build a Dream On 4’27

4. My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It 3’16

5. Tiger Rag 1’26

6. Now You Has Jazz 6’51

7. High Society 3’03

8. Ole Miss Rag 3’48

9. When I Grow Too Old to Dream 4’17

10. Tin Roof Blues 5’18

11. Yellow Dog Blues 3’00

12. When the Saints Go Marching in 3’33

13. Struttin’ With Some Barbecue 5’51

14. Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen 3’13

15. Blueberry Hill 3’27

16. The Faithful Hussar 5’10

17. St. Louis Blues [feat. Jewel Brown] 3’36

18. After You’ve Gone 3’23

19. Mack the Knife 4’52