- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

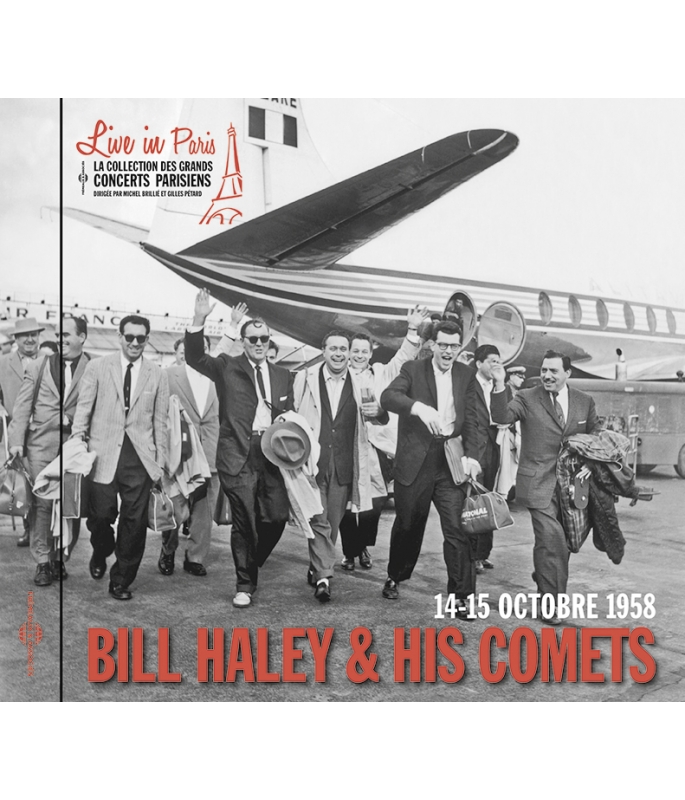

LIVE IN PARIS

BILL HALEY

Ref.: FA5671

EAN : 3561302567129

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 50 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

LIVE IN PARIS

LIVE IN PARIS

Bill Haley & His Comets were the rst ever rock stars that came to sing and play in France. As the American musicians begged the audience to sit down, so as to be able to carry on playing, their two, long-awaited Paris shows reached unimaginable heights. Bruno Blum tells how, with extraordinary energy and very fast tempos, The Comets electrified the legendary Olympia beyond all expectations. In the darkest hours of the Algerian crisis, this exceptional document shows the cathartic power of a new music, that, for the rst time, allowed young French people to unwind at a major rock concert. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The Live in Paris collection by Michel Brillié allows listeners to hear previously-unreleased recordings (made at concerts and private- or radio-sessions) by the great 20th stars in jazz, rock & roll and song. These “live” takes, and the artists’ rapport with their audiences, gives these performances an additional soul and sensibility in counterpoint to the rigorous demands of studio recordings. Particular care was taken when restoring the sound of these tapes in order to meet CD standards while preserving the original colours of the period. Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

ROCK AROUND THE CLOCK

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE...

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Introduction By Mc Jean Marie ProslierJean-Marie ProslierJM Proslier00:00:401958

-

2The Saints Rock And RollBill Haley & His CometsBill Haley00:02:541958

-

3Shake Rattle And RollBill Haley & His CometsCharles E. Calhoun00:02:211958

-

4Rudy's RockBill Haley & His CometsBill Haley00:04:181958

-

5For You My LoveBill Haley & His CometsPaul Leon Gayten00:02:391958

-

6Beecher Boogie WoogieBill Haley & His CometsFrancis Beecher00:03:481958

-

7I'M Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A LetterBill Haley & His CometsJoe Young00:02:381958

-

8Jump ChildrenBill Haley & His CometsInconnu00:02:381958

-

9Billy Williamson SpeaksBill Haley & His CometsBilly Williamson00:02:041958

-

10I'M In Love AgainBill Haley & His CometsFats Domino00:02:111958

-

11Mambo RockBill Haley & His CometsBix Reichner00:02:191958

-

12See You Later AlligatorBill Haley & His CometsBobby Charles00:01:441958

-

13Rock Around The ClockBill Haley & His CometsMax Freedmann00:04:261958

-

14Beecher Boogie WoogieBill Haley & His CometsFrancis Beecher00:03:231958

-

15Rock A Beatin' BoogieBill Haley & His CometsBill Haley00:02:001958

-

16Razzle DazzleBill Haley & His CometsCharles E. Calhoun00:01:521958

-

17TequilaBill Haley & His CometsChuck Rio00:04:181958

-

18Mc Comments / ApplauseBill Haley & His CometsJM Proslier00:01:551958

-

19Giddy Up A Ding DongBill Haley & His CometsFreddie Bell00:02:391958

Bill Haley Live FA5671

BILL HALEY & HIS COMETS

14-15 octobre 1958

Live in Paris

La collection des grands

concerts parisiens

Dirigée par Michel Brillié et Gilles Pétard

Bill Haley & His Comets « Live in Paris » 14-15 octobre 1958

Par Bruno Blum

Elvis Presley1 n’est jamais venu en France.

Ces dimanche et lundi soirs d’octobre 1958, quand ces deux concerts de Bill Haley & his Comets ont été enregistrés par les techniciens d’Europe 1 devant un Olympia en absolu délire, aucun des grands noms du rock n’avait encore pénétré sur le territoire français. On n’avait rien eu. Pas de Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly — personne2. En pleine ségrégation raciale, ne parlons même pas des rockers afro-américains — Roy Brown, Tiny Bradshaw, Big Joe Turner, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Bo Diddley ou Chuck Berry3 : rien de rien. Gene Vincent n’irait pas en Angleterre avant décembre 1959. Seuls les obscurs Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, qui étaient passés à l’Olympia en 1957 (ce qui explique peut-être que Haley chante ici leur album Giddy Up a Ding Dong en rappel), sont l’exception qui confirme la règle. Le rock’n’roll était bien lointain.

À Londres, Marty Wilde n’était en scène que depuis six mois. Tommy Steele avait eu quelques succès outre-manche mais comme celles de Cliff Richard, qui commençait seulement à enregistrer, ses chansons n’avaient souvent de rock que le nom, le costume et la coiffure. Larry Parnes, producteur de télé gay, lançait ses boys bands adolescents amateurs, lookés et bananés et vendait des disques aux gamines. Pour l’attitude, la testostérone et le son, il faudra attendre les Beatles, qui étaient à peine formés et cherchaient des bistrots où jouer le week-end — et les Who et les Rolling Stones quatre ans plus tard. Vince Taylor avait tout juste sorti sa première chanson. On était très loin du compte.

À Paris, Johnny Hallyday ado venait de se faire siffler sur la petite scène de L’Orée du Bois pour la première fois. Le rock avait surgi dix ans plus tôt des ghettos noirs de l’Amérique de Harry Truman, entre guerre mondiale et guerre de Corée. Aux États-Unis, depuis le triomphe d’Elvis début 1956 le rock’n’roll était un phénomène de société depuis trois ans, mais en France le rock existait surtout à travers de rares disques importés et quelques moments comiques comme le « Rock’n’Roll Mops » d’Henry Salvador ou le génial « Fais-moi mal Johnny » écrit par Boris Vian pour Magali Noël en 1956 et interdit à la radio. Le rock était décrié dans la presse jazz et absent des radios4.

En vérité, en dehors de quelques films impossibles à voir comme The Girl Can’t Help It (La Blonde et moi de Frank Tashlin, 1956) et Blackboard Jungle (Graine de violence de Richard Brooks, 1955, interdit en Angleterre, dont le générique défilait au son de Bill Haley chantant Rock Around the Clock) les ados du baby boom français ne rigolaient pas tous les jours dans la grisaille des années cinquante. Le pic de natalité avait commencé en 1942 au son du « travail, famille, patrie » du Maréchal Pétain et en 1958 les écoles et lycées étaient aussi sévères que bondés. La guerre d’Algérie faisait rage. Alors que Bill Haley entrait en scène ce soir-là, au même moment beaucoup de papas des ados présents au concert crapahutaient dans le désert algérien en treillis militaire. En mai 1958 après le putsch d’Alger où de louches généraux exigeaient le retour du général de Gaulle, et après une crise politique grave Charles de Gaulle venait d’être désigné par René Coty comme président du Conseil, notamment pour calmer la révolte des Français d’Algérie craignant l’indépendance du pays. La Cinquième République venait de naître d’un référendum national mené par De Gaulle dix jours avant le concert du 14 octobre. L’automne 1958 était ébranlé par une série d’attentats algériens sur tout le territoire de France métropolitaine. Le 29 septembre, deux semaines avant ces deux concerts, un attentat avait touché une usine à La Courneuve en banlieue parisienne et une bombe avait explosé dans le Paris-Turin. La tension était totale. Le froid d’octobre recouvrait déjà la France. La nuit recommençait à tomber tôt et juste un mois après la rentrée des classes, la jeunesse frustrée rêvait de se défouler, de se divertir.

À l’entrée de l’Olympia, ça sentait la frite et les flonflons. Le rock et son vent de libération arrivaient d’une autre planète. Seule la comète de Haley allait passer, mais elle prouvait indiscutablement que le rock existait, qu’il brillait au fond de la nuit. Les vedettes de variété de l’époque avaient pour nom Édith Piaf, qui n’avait rien d’une marrante, ou Annie Cordy, qui en était une. C’était les débuts de la télévision en noir et blanc. On y voyait aussi Luis Mariano et ses opérettes ringardissimes. Si l’on aimait l’esprit et la poésie il fallait chercher du côté de Mouloudji et Georges Brassens. Les nouvelles stars s’appelaient Jacques Brel, Gilbert Bécaud, qui avait provoqué quelques scènes d’hystérie (féminine) sur scène en 1955, et Charles Aznavour. Ce sont eux qui passaient à l’Olympia pendant cette période et avec tout le respect qu’on leur doit, on pourrait quand même dire que leur musique n’était pas vraiment hyper excitante. Elle ne donnait en tous les cas pas envie de danser en sautant en l’air, de casser des fauteuils ou de jeter son soutif pointu à forme «obus» sur la scène en hurlant.

En revanche, pas besoin d’avoir fait la Media School pour comprendre au bout de quelques secondes d’écoute de cet album que la fureur de vivre était dans la salle. Le rock, le vrai, venait débarquer en pétaradant sur la plage du boulevard des Capucines et les alliés étaient là pour l’accueillir à bras ouverts. Les mômes étaient dans tous leurs états et ça s’entend haut et fort. Le groupe était au point, leur musique irrésistible était un appel au ralliement, à la fête, presque à la rebellion. Venu de Pennsylvanie avec son spectacle super rodé (il avait douze ans de tournées dans les pattes et plusieurs gros succès au compteur), Bill Haley arrivait en terrain quasi vierge. Bill Haley & the Comets étaient logiquement attendus par les jeunes parisiens débutants en la matière comme une sorte de messie. Les gamins allaient enfin voir en chair et en os une légende du rock digne de ce nom5. Ce n’était pas Chuck Berry le génie de la guitare, ni Elvis la scandaleuse superstar et encore moins l’hystérique Little Richard, mais depuis Rock Around the Clock, See You Later Alligator et autres titres implacables, Haley était une vraie star et ça suffisait amplement. Une authentique vedette américaine. Et sa musique n’avait rien à voir avec celle d’Annie Cordy, Mireille ou Francis Lemarque (avec tout le respect qu’on leur doit).

En ces années où les chanteurs, ici prenant le micro chacun leur tour, ne disposaient pas de haut-parleurs de retour de son sur scène, ça chantait quand même juste dans le raffut général — un vrai miracle, et beaucoup de métier. Ce disque documente l’aube d’un nouvel âge, les aurores d’une époque de libération mentale, physique, spirituelle et sexuelle, d’une renaissance. La génération d’après-guerre arrivait presque à maturité et commençait enfin à tourner la page des années noires, des années grises, des années de plomb. Malgré le public qui tape dans ses mains à contretemps, à l’envers du rythme, comme toujours dans les concerts en France, on sent à chaque note le vent de l’histoire qui souffle, le vent qui tourne. Les mirifiques années soixante approchaient déjà, inespérées. Presque dépassé par la révolution rock qu’il avait largement contribué à allumer, Bill Haley était néanmoins ancré dans un passé encore très proche.

Le rock/swing zazou des années quarante avait ses lettres de noblesse ; le jazz était la forme musicale de la beat generation6, il séduisait les plus branchés des jeunes Français mais pour les gavroches de la rue, pour les blousons noirs de Ménilmontant qui ne fréquentaient pas les caves existentialistes de Saint-Germain des Prés, le compte n’y était pas. Bill Haley n’a jamais caché son goût pour le jazz de la période swing, qui était orienté vers la danse et avait accouché du rock à 100 %7. La formule qui fit le succès de Haley est son adoption des musiques rock afro-américaines comme Jump Children ; pour ce faire il avait laissé tomber son répertoire country, comme il est détaillé dans notre coffret trois CD The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1962 (satisfaction garantie).

Sur cet album en public le répertoire jazz est donc bien présent, mais accéléré, bombardé par la batterie binaire de Ralph Jones : When the Saints Go Marching In (un negro spiritual devenu un standard jazz) est mis à jour dans cette version rock intitulée The Saints’ Rock and Roll. « When the Saints » figurait au répertoire de Louis Armstrong et Sidney Bechet, qui menaient alors le renouveau du jazz traditionnel, très populaire en France à cette époque. Le 19 octobre 1955, un an exactement avant le deuxième concert de Haley, à 58 ans Sidney Bechet avait donné un concert gratuit à l’Olympia : cinq mille personnes s’étaient présentées et la soirée avait dégénéré en émeute, les spectateurs forçant le barrage de police, envahissant la salle de deux mille places (deux cents fauteuils cassés, dix blessés, deux millions de dégâts), ce qui explique l’insistance du présentateur Jean-Marie Proslier à ce que les spectateurs restent assis pour que Bill Haley soit autorisé à jouer. Tout le monde sentait bien le destroy monter. La casse sera d’ailleurs à la mode dans les concerts de rock à Paris un an ou deux plus tard, notamment aux concerts de Vince Taylor.

I Want to Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter avait été rendu célèbre par le roi du piano stride Fats Waller en 1935. Sans oublier Beecher Woogie Woogie (deux fois ici) un instrumental dans la tradition du « jump blues » des orchestres de jazz des années 40. Et puis Shake, Rattle and Roll n’était-il pas à l’origine un succès blues de Big Joe Turner (1954), enregistré avec un orchestre swing d’instruments à vent ? Idem pour For You my Love, une chanson de Paul Gayten, qui menait le meilleur orchestre de jazz/swing/blues de l’après-guerre à la Nouvelle-Orléans. L’orchestre de Gayten a d’ailleurs cédé sa place de roi du swing de Louisiane à la formation de Dave Bartholomew, qui composa bientôt I’m in Love Again avec Fats Domino en 19558. Le guitariste de Haley, Franny Beecher, jouait d’ailleurs dans l’orchestre de jazz de Benny Goodman avant de rejoindre les Comets. On peut l’entendre ici piloter une splendide et rare Gibson Les Paul Custom de 1956 à doubles micros P90 — une guitare particulièrement recherchée soixante ans plus tard — qui lui avait été offerte par Gibson. Bill, lui, avait reçu de Gibson une rare L-7C noire de 1956, équipée d’un micro flottant à l’ancienne, également entendue ici.

Quant au Rudie’s Rock du saxophoniste ténor Rudie Pompilli, joué ici sur un tempo hystérique, son rythme ressemble beaucoup aux instruments du saxophoniste «honk» Big Jay McNeely sur des titres comme « The Goof » en 1952. La formule est donc ici le swing ternaire de papa accéléré et bastonné en un mode binaire massif que même les Cramps n’auraient pas renié trente ans plus tard. C’est sans conteste le cas sur cette version supersonique, impeccable, de Rock Around the Clock joué en rappel le premier soir. Rock Around the Clock était bien entendu le gros succès du groupe (environ quarante millions d’exemplaires écoulés en soixante ans, l’une des plus grosses ventes de l’histoire de la musique populaire). Il était paru en 1955 et la publication européenne contenait quatre titres (e. p.) devenus célèbres, dont trois étaient logiquement interprétés sur scène : Mambo Rock, Rock Around the Clock et See You Later, Alligator. Après ce triptyque envoyé à vitesse supersonique, le public était à leurs pieds. La salle disjonctait. Tequila, le gros tube rock du moment (The Champs), donnait le coup de grâce : Bill Haley, fidèle à sa réputation, était bien le grand passeur du rock, un genre qu’il a été le premier à faire découvrir au grand public blanc. Ses choix artistiques étaient à la fois osés et avisés ; ils lui ont permis de couper à une carrière ennuyeuse (et mal payée) de chanteur de bal country. Les arrangements amphétaminés des Comets suractivent ici toutes ces compositions, jouées ici à un tempo complètement punk, inimaginable pour qui ait jamais pu supposer que Bill Haley était un musicien conventionnel. Alors voilà.

Bruno Blum, janvier 2017

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2017

1. Lire le livret et écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA 5361) et Volume 2 1956-1957 (FA 5383).

2. Lire les livrets et écouter The Indispensable : Gene Vincent 1956-1958 (FA 5402), Volume 2 1958-1962 (FA 5422), Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA 5425), Roy Orbison 1956-1962 (FA 5438), Jerry Lee Lewis et Buddy Holly (à paraître).

3. Lire les livrets et écouter The Indispensable : Little Richard 1951-1962 (FA 5607), Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA 5376), Volume 2 1959-1962 (FA 5406) et Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA 5409).

4. Lire le livret et écouter Anthologie du rock fifties en français 1956-1960 (FA 5479).

5. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1961 (FA 5465).

6. Lire le livret et écouter Beat Generation - Hep Cats, Hipsters & Beatniks 1936-1962 (FA 5644).

7. Lire le livret et écouter Race Records - Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600).

8. Lire le livret et écouter Fats Domino 1949-1962 (à paraître chez Frémeaux et Associés), qui contient la version originale de I’m in Love Again.

Bill Haley & His Comets Live in Paris Oct 14-15 1958

by Bruno Blum

Elvis Presley never once came to France1.

On these Sunday and Monday nights in October, 1958, as these two Bill Haley & his Comets shows were being recorded by Europe N.1 radio sound engineers before an audience consumed by an absolute delirium, none of the great names of rock music had yet entered French territory. We had seen nothing. No Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis or Buddy Holly — no one2.

Racial segregation was still in full swing, so let’s not even mention the African-American rockers — Roy Brown, Tiny Bradshaw, Big Joe Turner, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry3. None at all.

Gene Vincent would not make it to England until December of 1959. Only the obscure Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, who’d somehow made it to the Olympia Theatre stage in 1957 (which perhaps explains why Haley sang their song Giddy Up a Ding Dong as an encore here) are the exception that proves the rule. Rock ‘n’ roll had been and still was so distant.

In London, Marty Wilde had only been performing onstage for about six months. Tommy Steele had had a few hit records over the channel, but pretty much like Cliff Richard’s, who was just beginning his recording career, the only things his songs had in common with rock was the name, the clothes and the hair style. Larry Parnes, a gay TV producer, launched his quiffed, amateur, teenage “boy bands” with a suitable look, and sold records to teeny girls. For attitude, testosterone and sound you’d have to wait for The Beatles, who had just about formed and were looking for venues to play in at week-ends, then the Who and the Rolling Stones some four years later. Vince Taylor had just released his first song. We were well wide of the mark.

In Paris, a teen Johnny Hallyday was just getting whistled off for the first time on the tiny L’Orée du Bois stage. Rock‘n’roll, as a musical form, had arisen ten years earlier out of the black ghettoes of Harry Truman’s America, wedged somewhere between World War II and the Korean War. In the United States, since Elvis’ triumph in early 1956, it had been a craze for over three years, but in France, rock mainly existed through a few, rare, imported records and some comic moments, i.e. Henry Salvador’s “Rock’n’Roll Mops” or a song of genius, “Fais-Moi Mal Johnny”, written by Boris Vian for Magali Noël in 1956 and banned from the radio. Rock was put down in the jazz press and was completely absent from the radio4.

In truth, apart from a few hard-to-see films, such as Frank Tashlin’s The Girl Can’t Help It (1956) and Richard Brooks’ Blackboard Jungle (1955), which was banned in England, and in which you could hear Bill Haley singing Rock Around the Clock during the film credits, French baby-boom teenagers did not have much to laugh about in the dull 1950s. The birthrate peak had started as early as 1942, to the sound of Marshall Pétain’s “travail, famille, patrie” (work, family, homeland). By 1958 schools were still as strict as they were overcrowded. The Algerian war was raging. As Bill Haley walked onstage that evening, at that same, exact moment many of the teenagers present at the show had their daddy trudging in the Algerian desert, wearing a battledress.

In May of 1958, after the Algiers putsch, where shady generals demanded the return of General De Gaulle, and after a major political crisis, Charles de Gaulle was chosen by René Coty as the new Prime Minister. This was done, in part, to cool down the French colonials of Algeria, who feared that the country was going to be granted independance. The Fifth Republic was born out of a referendum thrown in by De Gaulle just ten days before this October 14th show started.

The autumn of 1958 was shaken by a series of terrorist attacks on French metropolitan soil. On September 29th, just two weeks before these two shows, an attack had hit a La Courneuve factory in the Paris suburbs and a bomb had exploded on the Paris-Turin train. Tension was at a peak. The October cold had begun and France was already shivering. The nights were drawing in again and, just a month after the start of the school year, a frustrated youth dreamed of entertainment, of letting off steam.

It smelled of French fries and oompahs at the Olympia door. Rock and its wind of liberation seemed to be blowing from another planet. Only the Haley comet was going to pass by, of course, but it undisputably proved that rock really existed, that it was twinkling away somewhere in the night’s deep blackness. In those days the pop stars were named Édith Piaf, who wasn’t exactly a comic character, or Annie Cordy, who was.

These were the early days of black and white television. You could see Luis Mariano and his tacky, old-fashioned operettas on it. If you liked spirit and poetry, you could check out Mouloudji and Georges Brassens. The new stars were Jacques Brel, Gilbert Bécaud, who’d sparked some (female) hysteria at the Olympia in 1955, and Charles Aznavour. They were the regulars at the Olympia at this time, and with all due respect, it still could be said that their music was not really that hyper exciting. Certainly it did not make you feel like dancing, jumping up in the air, breaking chairs or, if you happened to be female, throwing your sharp “bullet” bra onstage, screaming, did it?

On the other hand, no need to study at Media School to understand that, after listening to this record for a few seconds, rebels without a cause were in the house. Rock, true rock, had disembarked, putt-putting its way along the Boulevard des Capucines beach and allied forces were right there to welcome it with arms wide open. The kids were all in a state - and you can hear it loud and clear on this recording. The band was up and running, their compelling music a rallying cry, a call to party, almost to rebel.

Bill Haley had come from Pennsylvania with his well-proven show (he had twelve years of touring on the taximeter and a bunch of major hits under his belt), and he literally hit near-virgin ground there. As logically expected, Bill Haley & the Comets were hailed by young, Parisian newcomers as a sort of messiah. Those kids were at long last able to see in the flesh an American rock legend worthy of the name5. This was not Chuck Berry, the guitar genius, nor Elvis, the scandalous “Pelvis” superstar. Even less so, the hysteric Little Richard. But, since Rock Around the Clock, See You Later, Alligator and a few more tough tunes, Haley had become a true star and this was way good enough. A genuine American star. Plus, his music had nothing to do with that of Annie Cordy, Mireille or Francis Lemarque — with all due respect.

In those days singers — each taking their turn at the mike here — didn’t get any monitor loudspeakers to hear themseves onstage, but the team still sang in tune, in spite of the overall racket — a true miracle, thanks to plenty of experience on the job. This disc documents the dawn of a new age, the daybreak of a time when a mental, physical, spiritual and sexual revolution, a renaissance, was just beginning to arise. The post war generation was just coming of age and was finally turning the pages of the black years, the grey years, the lead-weight years. In spite of the audience clapping their hands offbeat — the wrong way around the rhythm, as is still the custom at all concerts in France — one can feel the wind of history blowing, and that wind shifting with every note. The fabulous, unhoped-for Sixties were already on their way. Almost overwhelmed by the rock revolution he had widely contributed to spark off, Bill Haley was nevertheless anchored in a near past.

1940s rock/swing/zazou music had its prestige; jazz was the musical form of the beat generation6. It appealed to the hippest of the French youth. But to the street-wise Parisian urchins, to the Ménilmontant leather jacket-clad rockers who did not hang out in existentialist basement clubs in Saint-Germain des Prés, this just wasn’t enough. Bill Haley, though, had never concealed his taste for jazz from the ‘swing’ period, which was dance-oriented and had 100% given birth to rock ‘n’ roll. Adopting African-American music, such as Jump Children was the formula that made Haley. To achieve this, he had dropped his country music style, as detailed in our triple CD set The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1962 (satisfaction guaranteed).

On this live album the jazz repertoire is therefore present, but it is sped up, bombed away by Ralph Jones’ binary drum set: When the Saints Go Marching In (a negro spiritual that had become a jazz standard) was updated to a rock version named The Saints’ Rock and Roll. “When the Saints” was on Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet’s set list, at a time when they led the trad jazz revival, which was very popular in France then.

On October 19, 1955, one year exactly before Haley’s second show, a 58 year-old Sidney Bechet had given a free concert at the Olympia. Five thousand people showed up and the evening degenerated into a riot as punters forced their way through the police roadblock and stormed the two-thousand seater theatre (two hundred chairs were broken, ten people injured and it cost two million francs in damage). Which explains MC Jean-Marie Proslier’s insistance that spectators sit down, in order for Haley to be allowed to continue playing. Everyone could feel the potential for destruction welling up. Breakage would, in fact, become fashionable at Paris rock concerts a couple of years later, most notably at Vince Taylor’s shows.

I Want to Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter was made famous by the king of stride piano, Fats Waller in 1935. Not to mention Beecher Boogie Woogie (twice), an instrumental in the jump blues tradition of Forties jazz orchestras. Also, wasn’t Shake, Rattle and Roll a Big Joe Turner blues hit (1954) originally recorded with a wind instruments swing orchestra?

The same goes for For You my Love, a song by Paul Gayten, who led the best postwar jazz/swing/blues orchestra in New Orleans. Gayten’s orchestra actually gave up its Louisiana “king of swing” crown to Dave Bartholomew, who wrote I’m in Love Again with Fats Domino in 19557. In fact, Haley’s lead guitar player, Franny Beecher, had played in Benny Goodman’s jazz orchestra before he joined The Comets. He can be heard here, piloting a rare, splendid, black 1956 Gibson Les Paul Custom with double P90 pickups — which, sixty years later, is one of the most sought-after guitars in the world — that Gibson himself had given him. In turn, Bill was offered a rare, black 1956 L-7C Gibson, complete with floating pickup, which can also be heard here.

Now, about tenor sax player Rudie Pompilli’s Rudie’s Rock, which is played here at a hysterically fast tempo, its rhythm sounds a lot like sax instrumentals by Big Jay McNeely on tunes like “The Goof” (1952). So the formula here is daddy’s swing, sped up and thrashed into a massive, binary mode that even The Cramps would not disown thirty years later.

It certainly is the case on this impeccable, high-speed version of Rock Around the Clock, played as an encore on the first night. Rock Around the Clock was, of course, the band’s big hit (forty million copies sold over the last sixty years, making it one of the biggest sellers ever in the history of popular music). It was first released in 1955, and the European extended-play record included four songs that all became famous, so three of them were most logically performed live: Mambo Rock, Rock Around the Clock and See You Later, Alligator.

Following this triptych, played at supersonic speed, the audience was metaphorically, not literally, lying at their feet. The entire crowd was exploding. The big rock hit of the moment, Tequila (by The Champs) gave it the coup de grâce: as ever worthy of his reputation, Bill Haley was popularizing rock, a genre he’d been the first to make a wide, white audience discover. His direction was both daring and wise; it enabled him to curtail his cheap, boring career as a singer in a country music dance band.

The amphetamine arrangements by The Comets on display here hyperactivate all of these songs, playing them at a completely punk-like tempo, which is hard to imagine for anyone who ever supposed Bill Haley was a conventional musician. So — here it is.

Bruno Blum, January, 2017

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2017

1. Read the booklet and listen to Elvis Presley and the American Music Heritage 1954-1956 (FA 5361) and Volume 2 1956-1957 (FA 5383).

2. Read the booklet and listen to our The Indispensable series: Gene Vincent 1956-1958 (FA 5402) and Volume 2 1958-1962 (FA 5422), Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA 5425), Roy Orbison 1956-1962 (FA 5438), and Jerry Lee Lewis and Buddy Holly (yet to be issued).

3. Read the booklet and listen to The Indispensible: Little Richard 1951-1962 (FA 5607), Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA 5376) and Volume 2 1959-1962 (FA 5406) and Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA 5409).

4. Read the booklet and listen to Anthologie Du Rock Fifties En Français, 1956-1960 (FA 5479).

5. Read the booklet and listen to The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1961 (FA 5465).

6. Read the booklet and listen to Beat Generation - Hep Cats, Hipsters & Beatniks 1936-1962 (FA 5644).

7. Read the booklet and listen to Fats Domino 1949-1962 (to be issued by Frémeaux & Associés), which contains the original version of I’m in Love Again.

Bill Haley & His Comets - Live in Paris 14-15 octobre 1958

1. Introduction by MC Jean-Marie Proslier 0’40

2. The Saints’ Rock and Roll (William John Clifton Haley aka Bill Haley, Milton Gabler aka Milt Gabler) 2’54

3. Shake, Rattle and Roll (Jesse Albert Stone aka Charles E. Calhoun) 2’21

4. Rudy’s Rock (Bill Haley, Rudy Pompilli) 4’18

5. For You My Love (Paul Leon Gayten) 2’39

6. Beecher Boogie Woogie (Francis Beecher aka Franny Beecher) 3’48

7. I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter (Joe Young, Frederick Emil Alhert) 2’38

8. Jump Children (unknown) 2’38

9. Billy Williamson speaks 2’04

10. I’m in Love Again [feat. Billy Williamson, vcl] (Antoine Dominique Domino, Jr. aka Fats Domino and David Louis Bartholomew aka Dave Bartholomew) 2’11

11. Mambo Rock (S. Bickley Richner aka Bix Reichner, Mildred Phillips, Jim Ayre) 2’19

12. See You Later Alligator (Robert Charles Guidry aka Bobby Charles) 1’44

13. Rock Around the Clock (Max C. Freedman, James E. Myers aka Jimmy Myers aka Jimmy DeKnight) 4’26

14. Beecher Boogie Woogie [featuring Franny Beecher, ld gtr] (Francis Beecher aka Franny Beecher) 3’23

15. Rock a Beatin’ Boogie (William John Clifton Haley aka Bill Haley) 2’00

16. Razzle Dazzle (Jesse Albert Stone aka Charles E. Calhoun) 1’52

17. Tequila (Danny Flores aka Chuck Rio) 4’18

18. MC comments & applause 1’55

19. Giddy Up a Ding Dong [feat. Al Pompilli vcl] (Fernandino Dominick Bello aka Freddie Bell, Peppino Lattanzi) 2’39

Bill Haley: vocals, rhythm guitar

Rudy Pompilli: tenor saxophone, backing vocals,

lead vocals on 4

Francis Beecher as Franny Beecher: vocals, lead guitar

Joe Olivier: rhythm guitar

Billy Williamson: vocals, steel guitar, lead vocals on 8 & 10

Johnny Grande: piano

Al Pompilli: bass, backing vocals, lead vocals on 5 & 19

Ralph Jones: drums

Jean-Marie Proslier: MC on 1 & 18

Produced by Jolly Joyce, Bruno Coquatrix and Lucien Morisse.

Recorded by Europe N°1 radio technical staff.

Olympia Theater, 28 boulevard des Capucines, Paris, France

Tracks 1 to 13: Sunday, October 14, 1958

Tracks 14 to 19: Monday, October 15, 1958

La collection Live in Paris :

Collection créée par Gilles Pétard

pour Body & Soul

et licenciée à Frémeaux & Associés.

Direction artistique et discographie :

Michel Brillié, Gilles Pétard.

Coordination : Augustin Bondoux.

Conception : Patrick Frémeaux,

Claude Colombini.

Fabrication et distribution :

Frémeaux & Associés.

With thanks to Claude Boquet, Chris Carter for proofreading, Bill Dubois, Jean Claude, Philippe Moch, Raymond Treillet and the gang.

Bill Haley & His Comets ont été les premières stars du rock à venir chanter et jouer en France. Très attendus, leurs deux concerts à Paris ont connu un succès inimaginable, où les musiciens américains suppliaient le public de se rasseoir pour pouvoir continuer à jouer. Bruno Blum raconte ici comment, avec une énergie extraordinaire, sur des tempos très rapides, les Comets ont électrifié le légendaire Olympia au-delà de toute espérance. Dans les heures les plus noires de la guerre d’Algérie, ce document exceptionnel révèle la puissance cathartique d’une nouvelle musique qui permit pour la première fois à de jeunes français de se défouler à un grand concert de rock.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

La collection Live in Paris, dirigée par Michel Brillié, permet de retrouver des enregistrements inédits (concerts, sessions privées ou radiophoniques), des grandes vedettes du jazz, du rock & roll et de la chanson du XXe siècle. Ces prises de son live, et la relation avec le public, apportent un supplément d’âme et une sensibilité en contrepoint de la rigueur appliquée lors des enregistrements studios. Une importance singulière a été apportée à la restauration sonore des bandes, pour convenir aux standards CD tout en conservant la couleur d’époque.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

Bill Haley & His Comets were the first ever rock stars that came to sing and play in France. As the American musicians begged the audience to sit down, so as to be able to carry on playing, their two, long-awaited Paris shows reached unimaginable heights. Bruno Blum tells how, with extraordinary energy and very fast tempos, The Comets electrified the legendary Olympia beyond all expectations. In the darkest hours of the Algerian crisis, this exceptional document shows the cathartic power of a new music, that, for the first time, allowed young French people to unwind at a major rock concert.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The Live in Paris collection by Michel Brillié allows listeners to hear previously-unreleased recordings (made at concerts and private- or radio-sessions) by the great 20th stars in jazz, rock & roll and song. These “live” takes, and the artists’ rapport with their audiences, gives these performances an additional soul and sensibility in counterpoint to the rigorous demands of studio recordings. Particular care was taken when restoring the sound of these tapes in order to meet CD standards while preserving the original colours of the period.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

BILL HALEY & HIS COMETS

1. Introduction by MC Jean Marie Proslier 0’40

2. The Saints’ Rock and Roll 2’54

3. Shake, Rattle and Roll 2’21

4. Rudy’s Rock 4’18

5. For You My Love 2’39

6. Beecher Boogie Woogie 3’48

7. I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter 2’38

8. Jump Children 2’38

9. Billy Williamson speaks 2’04

10. I’m in Love Again 2’11

11. Mambo Rock 2’19

12. See You Later Alligator 1’44

13. Rock Around the Clock 4’26

14. Beecher Boogie Woogie 3’23

15. Rock a Beatin’ Boogie 2’00

16. Razzle Dazzle 1’52

17. Tequila 4’18

18. MC comments & applause 1’55

19. Giddy Up a Ding Dong 2’39