- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

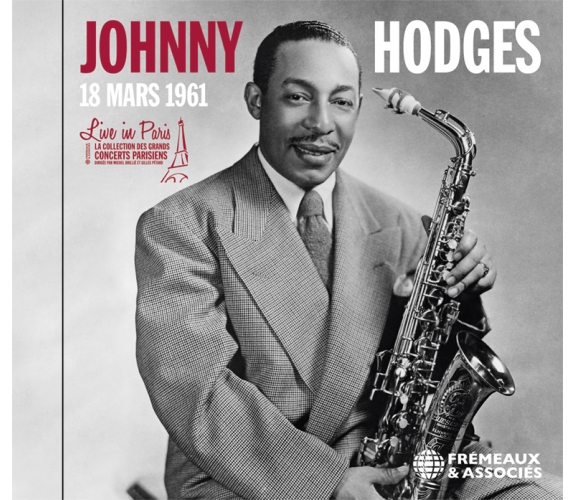

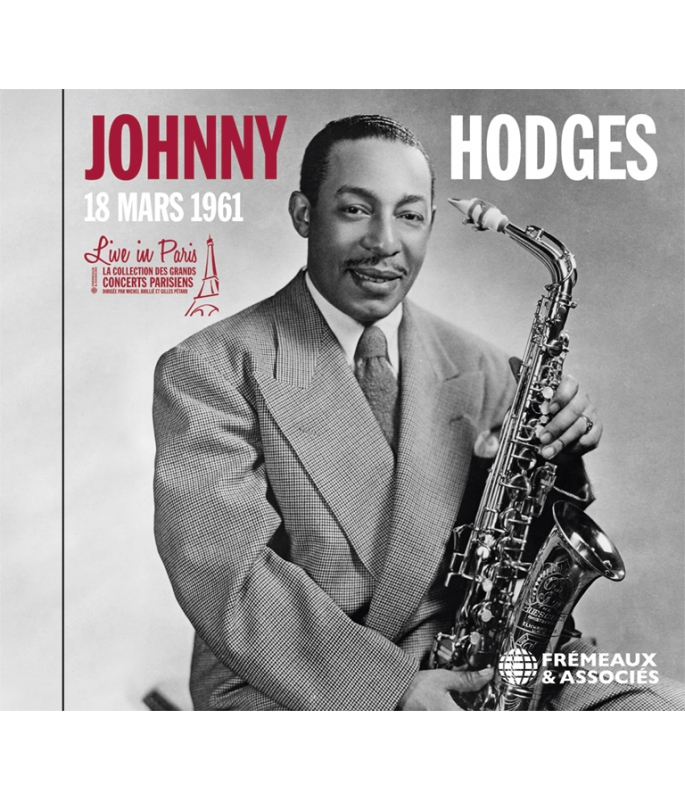

18 MARS 1961

JOHNNY HODGES

Ref.: FA5790

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 58 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

18 MARS 1961

- -

18 MARS 1961

With Johnny Hodges, the alto saxophone found itself in the hands of a goldsmith. As a member honoris causa of the Duke Ellington Orchestra from 1928 to 1970, Hodges’ delicate phrasing and incomparable talents as an improviser made him one of the most remarkable musicians in jazz history. In this previously unreleased live recording dating from 1961 he plays the great classics in Ellington’s material, titles he always incarnated with an incandescent grace.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The Live in Paris collection by Michel Brillié allows listeners to hear previously-unreleased recordings (made at concerts and private- or radio-sessions) by the great 20th stars in jazz, rock & roll and song. These “live” takes, and the artists’ rapport with their audiences, gives these performances an additional soul and sensibility in counterpoint to the rigorous demands of studio recordings. Particular care was taken when restoring the sound of these tapes in order to meet CD standards while preserving the original colours of the period.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

NEW YORK - CHICAGO - HOLLYWOOD 1928-1943

1958-1960

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Take the A TrainJohnny HodgesBilly Strayhorn00:02:501961

-

2Blues for MadeleineJohnny HodgesJohnny Hodges00:07:211961

-

3Mood IndigoJohnny HodgesIrving Mills00:02:251961

-

4(In My) SolitudeJohnny HodgesIrving Mills00:02:291961

-

5Satin DollJohnny HodgesDuke Ellington00:02:581961

-

6I Got It Bad And That Ain't GoodJohnny HodgesDuke Ellington00:02:491961

-

7Rockin' in RhythmJohnny HodgesDuke Ellington00:04:231961

-

8Don't Get Around Much AnymoreJohnny HodgesDuke Ellington00:03:501961

-

9Squeeze MeJohnny HodgesClarence Williams00:02:581961

-

10Do Nothing Till You Hear from MeJohnny HodgesBob Russell00:02:411961

-

11Rose of The Rio GrandeJohnny HodgesEdgar Leslie00:02:411961

-

12All of MeJohnny HodgesSeymour Simons00:02:271961

-

13On The Sunny Side of the StreetJohnny HodgesDorothy Fields00:04:111961

-

14Jeep's BluesJohnny HodgesJohnny Hodges00:04:491961

-

15PerdidoJohnny HodgesErvin Drake00:09:521961

Johnny Hodges FA5790

Johnny Hodges

Live in Paris -

18 Mars 1961

Johnny Hodges est un orfèvre du saxophone alto. Membre honoris causa du big band de Duke Ellington de 1928 à 1970, la délicatesse de son phrasé et son sens incomparable de l’improvisation, en font l’un des musiciens les plus remarquables de toute l’histoire du jazz. Dans ce live inédit enregistré en 1961, il interprète les grands classiques du répertoire ellingtonien, dont il incarne pour toujours la grâce incandescente.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

La collection Live in Paris, dirigée par Michel Brillié, permet de retrouver des enregistrements inédits (concerts, sessions privées ou radiophoniques), des grandes vedettes du jazz, du rock & roll et de la chanson du XXe siècle. Ces prises de son live, et la relation avec le public, apportent un supplément d’âme et une sensibilité en contrepoint de la rigueur appliquée lors des enregistrements studios. Une importance singulière a été apportée à la restauration sonore des bandes, pour convenir aux standards CD tout en conservant la couleur d’époque.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

With Johnny Hodges, the alto saxophone found itself in the hands of a goldsmith. As a member honoris causa of the Duke Ellington Orchestra from 1928 to 1970, Hodges’ delicate phrasing and incomparable talents as an improviser made him one of the most remarkable musicians in jazz history. In this previously unreleased live recording dating from 1961 he plays the great classics in Ellington’s material, titles he always incarnated with an incandescent grace. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The Live in Paris collection by Michel Brillié allows listeners to hear previously-unreleased recordings (made at concerts and private- or radio-sessions) by the great 20th stars in jazz, rock & roll and song. These “live” takes, and the artists’ rapport with their audiences, gives these performances an additional soul and sensibility in counterpoint to the rigorous demands of studio recordings. Particular care was taken when restoring the sound of these tapes in order to meet CD standards while preserving the original colours of the period.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

Johnny Hodges Live in Paris 18 Mars 1961

La chanson du lapin

Par Michel Brillié

C’est l’histoire du type qui n’avait « l’air de rien ». Une fois de plus, c’est Alain Gerber qui trouve les quelques mots définitifs pour un artiste hors normes. « Il n’avait l’air de rien de ce qu’il était. Il n’avait pas l’air attendri. Pas l’air attentif. Encore moins passionné. Il n’avait pas l’air généreux. Ou timide. Ou secret. Il n’avait pas l’air très heureux, ni très malheureux. Il avait l’air d’un homme qui s’ennuie et qui n’a pas de rêve… »

Quand il s’agit de l’un des saxophonistes alto les plus marquants de l’histoire du jazz, cela intrigue.

Johnny Hodges… De quel… bois (de roseau, pour être raccord avec la matière de son anche d’instrument), était-donc fait le géant de l’alto ? Petit dico de « lagomorphologie », étude du Lapin préféré de Duke Ellington.

Johnny Hodges était…

Chanteur

« Le meilleur chanteur du monde – qui d’autre ? » joli compliment du crooner Tony Bennett au Lapin. Cette qualité mélodique de l’alto de Johnny Hodges faisait dire au critique de jazz Stanley Dance qu’elle avait permis à l’orchestre du Duke de se passer de vocaliste pendant très longtemps. « Personne ne « chante » comme Johnny chante avec son alto. » Et le « chanteur » est couvert d’éloges : Charlie Parker, lors d’une écoute à l’aveugle de Hodges pour Leonard Feather en 1948, s’exclame : « Johnny Hodges, c’est le Lily Pons du sax ! Chapeau Johnny, il peut vraiment faire chanter son instrument. » Frank Sinatra, pourtant connu comme avare en compliments, lui dira à l’oreille : « John, tu es incroyable… » Hodges ne pipa mot, selon son habitude.

Cool

Toujours imperturbable, quoiqu’il arrive. Lors d’un concert du Duke à Boston, Hodges se retrouve à jouer un solo langoureux devant une bagarre au couteau de deux spectateurs excités. Les autres membres de l’orchestre font prudemment deux pas en arrière, mais Hodges, lui, ne bouge pas d’un centimètre et termine placidement son chorus.

Cool, blasé, … las, à tel point que, pour son sideman Shorty Rodgers, quand il montait sur scène, « il avait l’air d’aller à l’échafaud ».

Et avare de mots. Comme le dit le trompettiste Rex Stewart, « Il ne proférait pas trois mots si deux suffisaient. »

Épicurien

La gastronomie était l’un des sujets pour lesquels Johnny Hodges s’animait. Il était plutôt bon cuisinier, avec une préférence pour les côtes d’agneau aux petits pois. Amateur de Sauternes, on le voit déguster un verre de ce vin en 58 à la terrasse de Chez Lipp à Paris, devant l’appareil du photographe Herman Leonard. Il appréciait aussi la bière, suffisamment pour en écrire un morceau, « Rio Segundo », le nom d’une bière sud américaine à son goût.

Grognon

Et pas toujours bon camarade avec ses confrères. Pour une raison mineure, il se fâchait et ne parlait plus à la personne concernée pendant plusieurs mois. Barney Bigard, par exemple. Un soir au Birdland, Ben Webster était venu écouter l’orchestre d’Ellington, qu’il avait quitté plusieurs années auparavant. Comme c’était la coutume, on l’invita à venir jouer un morceau avec toute la bande. Webster vint s’assoir à côté de Johnny Hodges, et Duke lui demanda le titre de son choix. Webster choisit un classique d’Ellington, « I Got it Bad and That Ain’t Good ». Le saxophoniste en donna une version magnifique, alors que Hodges, rigide, lui fit ostensiblement la gueule. Après le départ de Webster, Hodges, fumant de rage, maugréa à son voisin Paul Gonsalves : « Mais c’est mon titre ! Ce mec le sait, c’est moi qui joue ce morceau ! »

Joueur (et chanceux)

Très fort au gin rummy, Hodges aimait jouer à la loterie, et à divers jeux de cartes. Il appréciait aussi montrer sa nouvelle fortune, en exhibant une « liasse mexicaine », un paquet de billets d’un dollar, recouvert d’un billet de cent. Sa chance a joué aussi pour sa santé personnelle : victime d’attaques cardiaques à trois reprises, à chaque fois, il s’est trouvé à proximité du meilleur hôpital de la région.

Marié

…Surtout à Duke Ellington. La carrière de Johnny Hodges est indissociable de celle de son chef. Ils jouèrent ensemble pendant plus de quarante ans, depuis cette toute première fois le 1er avril 1928 à Harlem au Cotton Club, pour la revue « Cotton Club Show Boat ». Jusqu’à la mort de Hodges en 1970, sa sonorité « magnifique, romantique, sensuelle » est restée intimement liée à la formation de Duke. « Notre orchestre ne sera plus jamais le même » dit Ellington lors de son enterrement au Harlem Masonic Temple.

Mais comme un vieux couple, il y a eu des hauts et des bas. Hodges a quitté la formation au début des 50s pour revenir quelques années plus tard. De petites jalousies minaient leur relation. Et comme tout couple, les dissensions tournaient autour de sujets éternels.

L’argent : de nature méfiante, Hodges voulait être payé chaque soir par Ellington. « Je n’ai confiance en personne, pas même en moi. Quand j’étais gamin et que je ramassais du coton dans les champs, on me payait tous les jours à la fin de la journée. Je ne veux rien devoir à personne, et inversement que personne ne me doive rien. » Sauf que Johnny Hodges était né à Boston, dans le Massachussetts, en Nouvelle Angleterre, bien loin des plantations de l’Alabama ou du Mississippi…

Autre grief financier qu’il partageait avec Billy Strayhorn : tous deux estimaient que le Duke les filoutait sur la paternité de droits d’auteurs. Johnny ou Billy vendaient à Ellington des idées abouties de morceaux, et quand le Duke en faisait des succès, Hodges essayait – sans y arriver – d’en obtenir plus d’argent... Alors pour se venger, lors de concerts, Johnny se tournait vers Ellington assis au piano et faisait mine de compter des billets… »

Et lorsque le Duke demanda au saxophoniste alto de reprendre son soprano pour rejouer certains morceaux, Hodges lui réclama un double cachet.

Ellington refusa.

Les femmes : La tonalité sensuelle de son jeu au saxophone était très efficace envers la partie féminine de l’audience. Un ami musicien a confié à Hodges que sa femme lui avait avoué, « Ne me laisse jamais seule avec Johnny, parce que quand je l’entends jouer, j’ouvre tout de suite la porte de la chambre. » Ellington de son côté a dit à Nat Hentoff : « quand Johnny prend un solo, à chaque fois un soupir énamouré se fait entendre de la part des dames, et d’ailleurs cette sensation est devenue partie intégrante de notre musique. »

Finalement, si Hodges était le moteur de cette sensualité, il pouvait avoir l’impression très nette qu’il préparait le terrain pour les nombreuses aventures amoureuses « after hours » du patron. Hodges, lui, menait en tournée une vie plutôt rangée, régulièrement accompagné de sa femme légitime.

L’indépendance : A plusieurs périodes, Hodges a pu estimer être trop dans l’ombre du grand orchestre, et avoir des velléités d’autonomie. « Johnny Hodges n’a pas eu besoin de beaucoup de persuasion quand il est venu rejoindre mon équipe en 1951. Tout ce qu’il voulait c’était un support financier et logistique qui lui permettrait de couper le cordon avec Duke. » C’est Norman Granz qui va le pousser à faire le pas. Par ailleurs, Granz voulait le produire comme artiste à part entière, il le signa donc sur son label et lui fit faire des tournées en nom propre. Ce fut Granz aussi qui organisa cette petite tournée européenne de Mars 1961 avec quelques cadors d’Ellington – Hodges étant revenu au sérail cinq années plus tôt – alors que le chef d’orchestre était à Paris, accaparé par la composition de la musique du film Paris Blues. Johnny et ses « géants ellingtoniens » passèrent par Stockholm, Helsinki, avant de s’arrêter à l’Olympia de Paris, puis enfin au Sport Palast de Berlin.

Dans ce partnership paradoxal, la vérité est peut-être à trouver chez Ellington. Dans son autobiographie Music is My Mistress, il précise que son saxophoniste alto « a une totale indépendance d’expression. Il s’exprime tel qu’il le souhaite avec son instrument, simplement. Il le dit à sa manière propre, et vous pouvez dire que c’est de l’art pur. »

Petit

Pas beaucoup plus d’un mètre soixante. Sa taille est sans doute à l’origine de son surnom, « Rabbit », le lapin. Harry Carney, son copain de toujours, trouvait qu’« il avait l’air d’un lapin timide et espiègle, quand il allait prendre un solo. » Et le sax ténor Johnny Griffin en rajoutait : « Quand il nous jouait toute cette musique magnifique, il ne montrait aucune expression …une vraie tête de lapin. » Johnny Hodges avait sa propre explication à ce surnom : « Quand j’étais étudiant à Boston, je courrais plus vite que les flics… » Mais c’est finalement Harry Carney qui fournit la version la plus basique : « C’est parce qu’il mangeait tout le temps des sandwiches tomate- laitue qu’il avait une tête de lapin. » Il fait donc partie des jazzmen affublés de noms d’animal : « Cat » Anderson, Willie « The Lion » Smith, Charlie « Bird » Parker, « Chick » Corea… Mieux vaut être un « Rabbit » qu’un « Cootie » - un pou- comme Charles (Cootie) Williams.

Pragmatique

Lorsqu’en tournée, il arrivait dans une nouvelle ville, Hodges était le premier à savoir où se trouve le cordonnier, le pressing le plus proche, ou toute autre boutique indispensable dans ces circonstances.

Il était réputé pour être un dénicheur d’« affaires » quand il est à l’étranger, cherchant à trouver des articles meilleur marché qu’aux USA (les valises, par exemple, dont il faisait une grande consommation en tournée).

Pur

Lors de l’enterrement de Hodges en 1970, Ellington a débuté l’hommage à son ami en évoquant cette qualité : « Ce n’était pas le plus grand showman du monde, ou la personnalité scénique la plus envoutante, mais c’était l’homme d’un son si beau que parfois les larmes vous montaient aux yeux. Tel était Johnny Hodges. Tel est Johnny Hodges. »

Le pianiste Earl « Fatha » Hines, l’une des figures emblématiques du jazz moderne, a rencontré et joué avec Hodges, alors qu’il avait une quarantaine d’années de plus. Depuis lors, son admiration est immuable :

« Avez-vous déjà bu de l’eau de source fraîche, naturelle ? Vous pouvez y ajouter des ingrédients, en faire de la limonade, de la bière, du café ou tout autre chose, mais lorsque vous avez soif, c’est difficile d’avoir mieux. Hé bien, pour moi, Johnny [Hodges] était comme cette eau de source - vraie, pure. Il n’a pas changé non plus. Peut-être qu’il a ajouté des idées au fur et à mesure, mais il a toujours été fidèle à lui-même. »

Michel Brillié

© 2021 Frémeaux & Associés

1. Alain Gerber, « L’air de Rien », texte coffret CD Johnny Hodges, The Quintessence, Frémeaux & Associés, 1995

2. Pendant l’enregistrement de « Indian Summer », in Francis A & Edward K , album avec Duke Ellington, 1969

3. Shorty Rodgers, Texte livret LP Perdido, Johnny Hodges & his Orchestra, 1955

4. Stanley Dance, The World Of Duke Ellington, Da Capo Press, 2000

5. Bill Crow, From Birdland to Broadway, Oxford University Press, 1992

6. Con Chapman, Rabbit’s Blues, Oxford University Press, 2019

7. Johnny Hodges - An interview with Henry Whiston, http://www.ellingtonia.com

8. Mercer Ellington, Duke Ellington In Person: An Intimate Memoir, Houghton Mifflin, 1978

9. Geoffrey C. Ward & Ken Burns : Jazz: A History of America’s Music, Knopf, 2002

10. Nat Hentoff, « Life Could Be a Dream When He Blew Sax », Wall Street Journal, Février 2002

11. David Hadju, Jazz, Oxford University Press, 2016

12. Con Chapman, Rabbit’s Blues, Oxford University Press, 2019

13. Stanley Dance, texte pochette The Smooth One, Johnny Hodges, Verve 1979

Johnny Hodges Live in Paris March 18th, 1961

Rabbit’s Song

By Michel Brillié

This is the story of the guy who “didn’t look like much”. Once again, it is Alain Gerber who finds the definite words for an extraordinary artist. “He didn’t look like anything he was. He didn’t look moved. Nor attentive. Even less passionate. He didn’t seem generous. Or shy. Or secretive. He did not look very happy, nor very unhappy. He looked like a bored man with no dreams...” When it refers to one of the most successful alto saxophonists in jazz history, it is intriguing. Johnny Hodges… Which… wood (or reed, to match the material of his instrument), was the alto giant made of? Here’s a short study of “lagomorphology”, the science of Duke Ellington’s favorite rabbit.

Johnny Hodges was ...

A “singer”

“The best singer in the world - what else?” A nice compliment from crooner Tony Bennett to the Rabbit. This melodic quality of Johnny Hodges’s alto sax had jazz critic Stanley Dance write that it made it possible for Duke’s orchestra to perform without a vocalist for a very long time. “Nobody ‘sings’ on the alto like Johnny Hodges”. And the “singer” was indeed praised: Charlie Parker, during a 1948 Leonard Feather blindfold test featuring Hodges, exclaimed, “Johnny Hodges… He’s the Lily Pons of sax! /... I always took my hat off to Johnny Hodges, ‘cause he can sing with the horn.”. Frank Sinatra, who was known to be stingy with compliments, confided, “John, you are amazing...” Hodges didn’t breathe a word, as always.

A cool one

Hodges was always unfazed, no matter what. At a Duke concert in Boston, Hodges was performing a languorous solo while two edgy guys were fighting with knives right by the stage. The other members of the orchestra carefully took two steps back, but Hodges didn’t move an inch and calmly ended his chorus. A cool, jaded, weary look: trumpet player Shorty Rodgers quipped that, when walking out to the mike, “he may look as though he’s on his last walk to the gallows.”

Stingy with words, also. As fellow band member Rex Stewart remembered, “He wouldn’t say three words if two were enough.”

An epicurean

Food was one of the topics Johnny Hodges was fond of. He was a pretty good cook, with a liking towards lamb chops with peas. He enjoyed wine, and particularly Sauternes sweet white wine: there’s a 1958 Herman Leonard black and white picture of Hodges pensively considering a glass of that drink while sitting at the sidewalk at Brasserie Chez Lipp in Paris. He also enjoyed beer, enough to write a number about it, “Rio Segundo,” the name of a South American beer to his liking.

A grumpy man

And he was not always a good friend to his colleagues. For some minor reason, he would get angry and not speak to the affected person for several months, such as Barney Bigard. On one evening at Birdland, tenor man Ben Webster had come to hear Ellington’s orchestra, years after he’d left it. As was customary, he was asked to sit in with the band. Webster climbed up onto the band stand next to Johnny Hodges, and Duke asked him what he’d like to play. Webster chose an Ellington classic, “I Got it Bad and That Ain’t Good”. The saxophonist gave it a magnificent rendition, while a sullen Hodges was openly sulking. After Webster left, Hodges, smoking with rage, grumbled to his neighbor Paul Gonsalves, “That was my tune! The man knows that was my tune!”

A gambler (and a lucky one too)

Hodges enjoyed playing the lottery and various card games. He boasted to have great success at a form of gin rummy called “tonk”. He also liked to show off his good fortune, by displaying a “Mexican Roll,” a wad of one-dollar bills, covered by a large one-hundred-dollar note. His luck also played a role in his personal health: he had three times happened to be near the best hospital in the region when he suffered heart attacks.

A married man

… Especially to Ellington. Hodges’s and Duke’s careers were inextricably attached. They played together for more than forty years, since that very first time on April 1, 1928 in Harlem at the Cotton Club, for the “Cotton Club Show Boat”. Until Hodges’s death in 1970, his “magnificent, romantic, sensual” sound remained intimately linked to Duke’s group. “Our band will never sound the same again,” said Ellington during Hodges’s funeral at the Harlem Masonic Temple. But like an old couple, they had their ups and downs. Hodges left the band in the early fifties, and came back a few years later. Pettiness marred their relationship. And like any couple, disagreements were fed by the same old topics.

Money: Being suspicious by nature, Hodges wanted to be paid in cash by Ellington every night. “I don’t trust myself or anyone else. When I was pickin’ cotton I used to get paid at the end of every day. I don’t want to owe nothin’ to anyone and have nothin’ owed to me either.” Except that Johnny Hodges was born in Boston, Massachusetts, New England, far from the cotton fields of Alabama or Mississippi...

Hodges shared another financial grievance with his friend composer Billy Strayhorn. They both felt Duke was cheating on them for copyright fees. Johnny or Billy would sell Ellington great ideas for songs, and when the Duke turned some of those into hits, Hodges tried - and failed - to get a better deal. .. In retaliation, on stage, Johnny would “turn to Ellington sitting at the piano and mime counting money…” And when once Duke asked the alto saxophonist to resume playing soprano for certain numbers, Hodges demanded double pay. Request denied by Ellington.

Women: Hodges’s sensual tone with his saxophone was spellbinding for the female part of the audience. A musician friend told Hodges that his wife had warned him, “Never leave me alone with Johnny, because when I hear him I open up the bedroom door.” Ellington from his part recalled with Nat Hentoff, “When Hodges soloed, inevitably a sigh would come from one of the dancers, and that feeling would become part of our music.” And though, if Hodges was the driving force behind this sensuality, he might have the distinct impression that he was “fattening frogs for snakes” for the leader’s many “after-hour” love affairs. Hodges himself led a rather quiet life on tour, usually accompanied by his legitimate spouse.

Independence: At certain times, Hodges may have felt that he was too overshadowed by the dimension of the orchestra, and therefore aspired to some autonomy. When he joined Norman Granz’s team in 1951, “I didn’t have to persuade Johnny” recalled the agent. “All he wanted was the financial and organizational support to permit him to pull the plug with Duke.” Norman Granz did urge him to take the step. Moreover, Granz wanted to produce him as an artist in his own right, so he signed him on his label and had him tour in his own name. It is Granz who organized this short European tour of March 1961 with a few top dogs from Ellington’s band. Hodges had returned to the group five years earlier. In the spring of ’61, Ellington was in Paris, all wrapped up writing the music score for the movie Paris Blues. So Johnny and his “Ellington Giants” stopped by Stockholm, Helsinki, then played at the Olympia in Paris, and finally at the Sport Palast in Berlin.

Even though their partnership seemed complex at times, Ellington set the record straight. For The World of Duke Ellington, Duke told Stanley Dance, “Johnny Hodges has complete independence of expression. He says what he wants to say on the horn and that is it. He says it in his language, which is specific, and you could say that his is pure artistry.”

A short one

Hodges was not much over five feet. His size is undoubtedly the origin of its nickname, “Rabbit”. Harry Carney, his lifelong friend, found that “he was shy, and skittish like a rabbit, for example, when it came to taking a solo” and tenor sax Johnny Griffin added: “He looked like a rabbit, no expression on his face while he’s playing all this beautiful music.” Johnny Hodges had his own explanation for this nickname: he was fast on foot, able to escape the Boston policemen running after the young student. “They never could catch me. I’d go too fast. That’s why I’m called Rabbit.” But it was ultimately his buddy Harry Carney who provided the most likely explanation: “Hodges looked like a rabbit when he regularly nibbled on lettuce-and-tomato sandwiches.” He is therefore one of the many jazzmen called with animal names, “Cat” Anderson, Willie “The Lion” Smith, Charlie “Bird” Parker, “Chick “Corea...” he was probably happier to be a “rabbit”, than a “cootie” like Charles (Cootie) Williams.

A pragmatic fellow

Upon arriving in a new town, Hodges was the first to scout new grounds to discover the location of the nearest shoemaker, dry cleaner, or other essential survival shop. Overseas, he was known to be a “bargain” hunter, looking for items that were cheaper there than in the US (he was a suitcase freak, for example, which he bought a lot of on tour).

A pure soul

At Hodges’s funeral in 1970, Ellington started his homage to a friend by evoking his pure sound: “He was never the world’s most highly animated showman or greatest stage personality, but a tone so beautiful it sometimes brought tears to the eyes - this was Johnny Hodges. This is Johnny Hodges.” Pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines, one of the icons of modern jazz, met and performed with Hodges when he was in his forties. Since then, his admiration has not changed: “You ever drink any cool, clean spring water? You can add things to it, make lemonade, beer, coffee, or what have you, but when you’re thirsty it’s hard to beat it just as it is. And it’s probably better for you than the kind hyped up with chlorine. Well, to me, Johnny [Hodges] was like that spring water – the real thing, unadulterated. He didn’t change either. Maybe he added ideas as he went along, but he was always true to himself.”

Michel Brillié

© 2021 Frémeaux & Associés

1. Alain Gerber, “L’air de Rien”, liner notes for CD box Johnny Hodges, The Quintessence, Frémeaux, 1995

2. During the recording of “Indian Summer”, in Francis A & Edward K, LP Frank Sinatra & Duke Ellington, Reprise 1969

3. Shorty Rodgers, Liner Notes for LP Perdido, Johnny Hodges & his Orchestra, 1955

4. Stanley Dance, The World Of Duke Ellington, Da Capo Press, 2000

5. Bill Crow, From Birdland to Broadway, Oxford University Press, 1992

6. Con Chapman, Rabbit’s Blues, Oxford University Press, 2019

7. Johnny Hodges - An interview with Henry Whiston, http://www.ellingtonia.com

8. Mercer Ellington, Duke Ellington In Person: An Intimate Memoir, Houghton Mifflin, 1978

9. Geoffrey C. Ward & Ken Burns: Jazz: A History of America’s Music, Knopf, 2002

10. Nat Hentoff, “Life Could Be a Dream When He Blew Sax”, Wall Street Journal, Fevrier 2002

11. David Hajdu, Jazz, Oxford University Press, 2016

12. Stanley Dance, The World of Duke Ellington, Da Capo Press ,2000

13. Con Chapman, Rabbit’s Blues, Oxford University Press, 2019

14. Id

Johnny Hodges & the Duke Ellington Giants Live in Paris 18 mars 1961

1. Take the A Train (Billy Strayhorn) 2’50

2. Blues for Madeleine (Johnny Hodges) 7’21

3. Mood Indigo (Irvin Mills / Barney Bigard - Duke Ellington) 2’25

4. (In My) Solitude (Eddie DeLange - Irvin Mills / Duke Ellington) 2’29

5. Satin Doll (Johnny Mercer / Duke Ellington - Billy Strayhorn) 2’58

6. I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good (Paul Francis Webster / Duke Ellington) 2’49

7. Rockin in Rhythm (Duke Ellington - Harry Carney - Irving Mills) 4’23

8. Don’t Get Around Much Anymore (Bob Russell / Duke Ellington) 3’50

9. Squeeze Me (Clarence Williams / Thomas « Fats » Waller) 2’58

10. Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me (Bob Russell / Duke Ellington) 2’41

11. Rose of the Rio Grande (Edgar Leslie / Harry Warren) 2’41

12. All of Me (Seymour Simons/ Gerald Marks) 2’27

13 On the Sunny Side of the Street (Dorothy Fields / Jimmy McHugh) 4’11

14. Jeep’s Blues (Johnny Hodges - Duke Ellington) 4’49

15. Perdido (Ervin Drake - Hans Lengsfelder / Juan Tizol) 9’52

Total time 58’44

Recorded by Europe N°1 Technical Staff

Recording date

March 18, 1961

Recording place

Olympia Theater, Paris, France

Produced by’ Daniel Filipacchi, Norman Granz & Frank Ténot

Personnel

Aaron Bell Bass

Lawrence Brown Trombone

Harry Carney Barytone Sax

Johnny Hodges Alto Sax

Ray Nance Cornet, Violin, Vocal

Al Williams Piano

Sam Woodyard Drums

Dedicated to Claude Boquet, Bill Dubois, Jean Claude, Philippe Moch, Raymond Treillet and the gang

La collection Live in Paris :

Collection créée par Gilles Pétard pour Body & Soul et licenciée à Frémeaux & Associés.

Direction artistique et discographie : Michel Brillié, Gilles Pétard.

Coordination : Augustin Bondoux.

Conception : Patrick Frémeaux, Claude Colombini.

Fabrication et distribution : Frémeaux & Associés.