- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

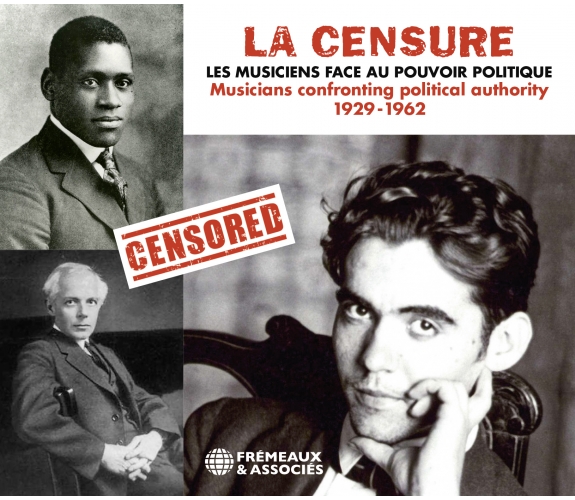

SERGUEI PROKOFIEV • BILLIE HOLIDAY • BORIS VIAN • AMALIA RODRIGUES

SERGUEI PROKOFIEV • BILLIE HOLIDAY • BORIS VIAN • AMALIA RODRIGUES

Ref.: FA5818

Artistic Direction : Teca Calazans & Philippe Lesage

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 43 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

SERGUEI PROKOFIEV • BILLIE HOLIDAY • BORIS VIAN • AMALIA RODRIGUES

All the composers and artists featured in this anthology incurred the wrath of censors who officially banned their works. The cultural views of such personalities as Stalin, Hitler, Franco or Salazar, not to mention McCarthy, had consequences including assassination, deportation and exile, and they led to a rejection of modernity. The value of works scorned by governments, however, has not been overlooked by history.

Teca CALAZANS et philippe LESAGE

CD1 : CONTRASTES (BARTOK) • STOMPIN’ AT THE SAVOY (BENNY GOODMAN) • EBONY CONCERTO (STRAVINSKY) • LULU – SUITE : ADAGIO (BERG) • FIVE PIECES FOR ORCHESTRA : SUMMER MORNING BY A LAKE (SCHOENBERG) • OPÉRA DE QUAT’ SOUS : EXTRAITS DES ACTES I, II ET III (BERTOLD BRECHT – KURT WEILL).

CD2 : SONATE POUR PIANO N° 8 (PROKOFIEV) • QUATUOR À CORDES N°8 (CHOSTAKOVITCH) • CONCERTO POUR VIOLON N° 1 : MOUVEMENTS PASSAGLIA, BURLESQUE (CHOSTAKOVITCH) • PRÉLUDE ET FUGUE OP 87 (CHOSTAKOVITCH).

CD3 : STRANGE FRUIT (BILLIE HOLIDAY) • BLACK GIRL (JOSH WHITE) • FREE & EQUAL BLUES (JOSH WHITE) • OL’ MAN RIVER (PAUL ROBESON) • FREEDOM (PAUL ROBESON) • MONOLOGUE FROM SHAKESPEARE’S OTHELLO (PAUL ROBESON) • HOLD ON (MARIAN ANDERSON) • UNCLE SAM SAYS (JOSH WHITE) • GARVEY’S GHOST (MAX ROACH) • ASAS FECHADAS (AMALIA RODRIGUES) • CAIS DE OUTRORA (AMALIA RODRIGUES) • MARIA LISBOA (AMALIA RODRIGUES) • POEMA DEL CANTE JONDO (GERMAINE MONTERO) • PERIBANEZ (GERMAINE MONTERO) • L’AMOUR SORCIER : DANSE RITUELLE DU FEU (ORCHESTRE DES CONCERTS DE MADRID) • CHANSON DE CRAONNE (ERIC AMADO) • LE DÉSERTEUR (BORIS VIAN) • LE GORILLE (GEORGES BRASSENS) • FAIS-MOI MAL, JOHNNY (MAGALI NOËL) • SANGUINE (YVES MONTAND).

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Contrast - VerbunkosBéla BartókBéla Bartók00:05:251940

-

2Contrats - PihneoBéla BartókBéla Bartók00:04:331940

-

3Contrast - SebesBéla BartókBéla Bartók00:03:001940

-

4Stompin' At The SavoyBenny GoodmanBenny Goodman, Chick Webb00:03:191936

-

5Ebony ConcertoIgor StravinskyIgor Stravinsky00:08:401946

-

6Lulu – Suite : AdagioAntal DoratiAlban Berg00:09:001961

-

7Five Pieces For Orchestra : Summer Morning By A LakeAntal DoratiArnold Schoenberg00:03:381961

-

8Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 1Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:02:061958

-

9Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 2Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:03:041958

-

10Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 3Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:01:251958

-

11Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 4Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:02:201958

-

12Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 5Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:01:551958

-

13Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 6Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:04:461958

-

14Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 7Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:01:501958

-

15Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 8Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:03:431958

-

16Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 9Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:04:221958

-

17Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 10Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:04:381958

-

18Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 11Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:02:321958

-

19Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 12Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:02:151958

-

20Opéra de Quat'sous : Extraits des actes I, II et III - 13Wilhem Brückner-RuggebergBertold Brecht, Kurt Weil00:01:251958

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Sonate pour Piano n°8 - Andante dolceSviatoslav RichterSergueï Prokofiev00:15:501962

-

2Sonate pour Piano n°8 - Andante sognandoSviatoslav RichterSergueï Prokofiev00:04:181962

-

3Sonate pour Piano n°8 - Vivace allegro ben marcatoSviatoslav RichterSergueï Prokofiev00:09:431962

-

4Quatuor à cordes n°8 - LargoBorodin QuartetDimitri Chostakovitch00:04:071962

-

5Quatuor à cordes n°8 - Allegro moltoBorodin QuartetDimitri Chostakovitch00:02:431962

-

6Quatuor à cordes n°8 - AllegrettoBorodin QuartetDimitri Chostakovitch00:03:501962

-

7Quatuor à cordes n°8 - LargoBorodin QuartetDimitri Chostakovitch00:05:081962

-

8Quatuor à cordes n°8 - Largo 2Borodin QuartetDimitri Chostakovitch00:03:051962

-

9Concerto pour violon n°1 - PassagliaDavid OïstrakhDimitri Chostakovitch00:13:281955

-

10Concerto pour violon n°1 - BurlesqueDavid OïstrakhDimitri Chostakovitch00:04:481955

-

11Prélude et fugue, op. 87 - PréludeEmil GuilelsDimitri Chostakovitch00:04:321955

-

12Prélude et fugue, op. 87 - FugueEmil GuilelsDimitri Chostakovitch00:06:321955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Strange FruitBillie HolidayLewis Allan00:03:081954

-

2Black GirlJosh WhiteJosh White00:03:001958

-

3Free & Equal BluesJosh WhiteEdgar Yipsel Harburg, Earl Robinson00:03:511958

-

4Ol’Man RiverPaul RobesonOscar Hammerstein, Jerome Kern00:04:051932

-

5FreedomPaul RobesonAir traditionnel00:01:561958

-

6Monologue From Shakespeare's OthelloPaul RobesonWilliam Shakespeare00:02:461958

-

7Hold OnMarian AndersonAir traditionnel00:02:251945

-

8Uncle Sam SaysJosh WhiteCuney Waring, Josh White00:02:431941

-

9Garvey's GhostMax RoachMax Roach00:07:551961

-

10Asas FechadasAmalia RodriguesYip Harburg, Earl Robinson00:02:531955

-

11Cais de OutroraAmalia RodriguesLuis Macedo, Alain Oulman00:03:261960

-

12Maria LisboaAmalia RodriguesLuis Macedo, Alain Oulman00:02:491960

-

13Poema Del Cante Jondo (Federico Garcia Lorca)Germaine MonteroFrederico Garcia Lorca00:07:581960

-

14Peribanez (Federico Garcia Lorca)Germaine MonteroFrederico Garcia Lorca00:01:481960

-

15L'amour sorcier (Manuel de Falla)Orchestre des Concerts de<br>MadridManuel De Falla00:04:521962

-

16La Chanson de CraonneEric AmadoAir traditionnel00:03:351952

-

17Le DéserteurBoris VianBoris Vian, Harold Berg00:03:301956

-

18Le GorilleGeorges BrassensGeorges Brassens, Georges Brassens00:03:181953

-

19Fais-Moi Mal, JohnnyMagali NoëlBoris Vian, Alain Goraguer00:02:231956

-

20SanguineYves MontandJacques Prévert, Henri Crolla00:02:431960

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Censorship

Musicians confronting political authority, 1929 - 1962

For political authorities, censorship is an act of strength. But it is not the only type of sanction practised in conflicts between those in power and the artistic world. Governments have a whole array of means of repression: disparagement of the artist concerned; belittling his or her conception of art; psychological pressures; imprisonment; banning publication; and censorship pure and simple. Here it will suffice to comment on historical fact, and how it reveals the destructive dimension of totalitarian regimes and their effects on artists’ destinies (quite apart from the ridicule to which their work was subjected.) All the sounds illustrating this anthology are compositions by artists who were vilified, to varying degrees, by political authority, yet history has retained their importance.

The backdrop to the censorship practised in this period is provided not only by Hitler and Stalin, who considered themselves incarnations of the tastes and desires of the people, but also the conservative ideologies of Salazar and Franco, plus certain democracies in the grip of anti-communist paranoia. The context would lead to exile on numerous occasions (many people, often Jewish, left their native country: Schoenberg, Bartok, Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler and Ernst Krenek would immigrate to the USA, and Roberto Gerhardt, Schoenberg’s sole Spanish pupil, would go to England). There were also executions (Garcia Lorca), deportations that were macabre (Viktor Ullmann, Pavel Haas, Hans Krasa and Gideon Klein all transited via Theresienstadt and Auschwitz), or imprisonment (Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Shostakovich’s friend, was sent to the gulag between February and the end of April 1953, and freed on the death of Stalin); and Alain Oulman was imprisoned in Portugal before he was expelled. Some, like Shostakovich, were obliged to repent before their peers, while others, equally celebrated, had their passports confiscated (Prokofiev, Paul Robeson or Leonard Bernstein).

“Music for degenerates” according to the Nazis

The formula for enforcing Nazi policy was introduced by this regime as soon as Hitler became Chancellor, with the aim of undoing everything that people had acquired during the Weimar Republic. From 1918 to 1933, the Republic went through a violent period in politics and also endured an economic crisis, none of which erased a cultural effervescence of which Berlin constituted the exceptional stage. The period saw people with a new vision of art develop a commitment that sometimes had its shadows. It is difficult to single out a common theme from among the ideas and productions of Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Paul Hindemith, Hanns Eisler or Kurt Weill, or the songs of Friedrich Hollaender, unless you choose their thrilling creativity and the intelligence with which they were enacted. But for some, that effervescence was unacceptable.

As soon as Hitler came to power in January 1933, the descent into hell took only a few months. Every personality who was Jewish found himself immediately excluded, hunted down, and deprived of his citizenship. Nor were Left-wing sympathisers spared, and people turned to exile in panic.

The exhibition known as Entartete Musik (“Degenerate Music”) held in Düsseldorf from May 24 to June 14, 1938 did nothing more than ratify an established fact. For Hans Ziegler, the exhibition’s curator, the phrase “degenerate music” designated not only 19th century Jewish composers like Mendelssohn, but also contemporary composers like Kurt Weill and Schoenberg, not to mention cabaret songs and “nigger jazz”. The poster by the graphic artist Ludwig Tersch marked the crystallisation of the hatred that Nazis held for the culture of the Weimar Republic. Even if the exhibition was given no more than a mild reception, the exhibits directly designated Bolsheviks, Jews and Negroes as those at fault for the “disintegration” of the authenticity of German art, and that destroying those responsible was an overriding duty.

To illustrate the sounds that lulled Berlin in the Weimar period, we have focused on genres and artists that were deemed “degenerate”. Strangely enough, Stravinsky was also singled out, probably due to his familiarity with jazz. Kurt Weill is present here, of course, like the Hungarian composer Bela Bartok, and the jazz clarinettist Benny Goodman, whose quartet no doubt greatly displeased the Nazis because it had two Negro musicians playing alongside two white Jews. As for Berg, his powerful influence on the world of opera couldn’t be ignored, nor that of Arnold Schoenberg, the father of dodecaphonic music.

Prokofiev and Shostakovich in the Stalin era

In the Soviet Union’s early years after the Revolution, freedom of creation was fragile and brief. In hindsight, one can glimpse that the social realism of Stalin was already germinating in the mind of Lenin, who detested the avant-garde in music, followed by the Communist Party’s decision to drown “cultural affairs” inside the tentacular Ideology and Propaganda Administration.

Once in power, Stalin would have no opposition to prevent him from letting his paranoia run free. He had a certain musical sensitivity, but what he was willing to accept was bound by his own perception of the subversive nature of specific works, as illustrated by the tragedy-comedy surrounding the Shostakovich opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. On 26 January 1936, Stalin attended a performance of the work, which had already enjoyed success for two years. Stalin hated it: the opera disobeyed Stalin’s instructions with regard to a language that was close to the masses. Two days later, a Pravda editorial entitled “Muddle instead of music” castigated the opera for its waves of intentionally jarring sounds and the “obscene” nature of certain scenes. Stalin’s word was law, and the editorial’s thinly veiled threat against the composer – the phrase was “This game can only end badly” – filled the 29 year-old Shostakovich with panic. He knew exactly what the remark really meant.

Shostakovich and Prokofiev were the two most visible composers of the day. They did not experience the gulag, but psychologically they had to affront devastating treatment during “The Great Purge”, including telephone calls from Stalin at night and having to read shameful statements of contrition aloud in front of their peers. In hindsight their ambivalent behaviour has somewhat faded: it is obvious that a flexible backbone was necessary to face the henchmen of “socialist realism” when one found oneself ranked in the category of “modernists” and “formalists”.

In February 1948, at the Central Committee’s offices, Andrei Zhdanov organised three days of debate with composers which concluded with the publication of a “historic decree” that imposed socialist realism and refuted the “formalism” of the so-called “modernist” composers. Following which, forty-two works were blacklisted, including the Shostakovich Symphonies 6, 7 and 9, plus Prokofiev’s Piano Sonatas No. 6 and No. 8. When the General Secretariat of the Union of Composers held its First National Congress, the “formalists” were urged to make amends. Shostakovich, tight-lipped and pallid, would read aloud a letter of self-flagellation that was slipped into his hands just before he stepped up to the podium.

Often positioned as one of fate’s eternal victims, Shostakovich was born in Saint Petersburg in 1906. In music he liked discord and parody, and appreciated the work of Berg and Krenek. He liked Sam Wooding’s Chocolate Kiddies (billed as a “negro operetta”), and also Bartok, Kurt Weill and Hindemith. As early as 1926 his first symphony was an immediate success, and from one commission to the next, plus other works whether worshipped or rejected, he would never cease to compose. His Fourth Symphony, considered his most ambitious work, would only appear much later: working in an environment that was suffocating psychologically, he’d gone back to his score just when the piece had already begun rehearsals. It constituted a challenge to those in power, and Shostakovich did not want to repent. But it didn’t prevent him from executing a spectacular stylistic U-turn with his Fifth Symphony, going as far as to write to officials of the Union of Composers: “This symphony is a Soviet artist’s creative response to the fair criticism formulated with regard to Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk.” Shostakovich is reported to have said to his son Maxim: “It is the determination of a strong man to BE.” The Seventh Symphony, broadcast over American radio on 19 July 1942 with Toscanini conducting, was perceived as a propaganda message from the USSR at war. Reading William T. Vollmann’s astonishing book Europe Central, one has a better understanding of the reasons that motivated him to write a symphony with such warlike and patriotic accents, music that is powerful, generous and filled with humanity, with all due respect to Bartok and Hindemith. For this anthology we wanted to illustrate the best of Shostakovich by selecting his disquieting Eighth Quatuor, his First Concerto for violin and the Fugue from his N°24 Prelude, a reference to Bach.

Prokofiev, born in Ukraine in 1891, was a nonchalant, handsome man with a look that said he was pleased with himself. He’d left the USSR at 26, when the Revolution came (it left him quite indifferent) and his Soviet passport allowed him to go first to America for four years, and then to France. Wearing a halo of prestige, he returned to his homeland in 1927 at the instigation of Stalin, even though his passport would be confiscated in 1938. Two works suited Stalin’s expectations of him: the music for Sergei Eisenstein’s film Alexander Nevsky, and a Fifth Symphony that had a very “Soviet” soul. His Symphony N° 6 dated 1947 was deemed displeasing because Stalin did not find it positive enough. Naturally so, because Prokofiev was above all the eulogist of “a new simplicity” (as he wrote in his diary), a kind of modernism rooted in the classical and romantic tradition that had no disdain for either irony or melancholy. The Piano Sonata N° 8 in B-flat major Op. 84, which you can find here, is one of the three so-called “War Sonatas” and is on a very different scale from his ballet Romeo and Juliet.

USA: Genius is colour-blind

On Easter Sunday 1939, during contralto Marian Anderson’s performance in front of a crowd of 75,000 people at the Lincoln Memorial, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes declared, “In this great auditorium under the sky, all of us are free. Genius, like justice, is blind. Genius draws no color lines.” The federal capital was teaching tolerance in a lesson that Richard Powers vibrantly echoed in his novel The Time of our Singing. We can see below, however, that black artists were not spared by politicians, and that their careers, not to say their lives, would suffer the consequences of that.

The tumultuous prelude leading to that memorable concert by Marian Anderson deserves closer examination. The Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.) had refused to give in to the contralto due to the colour of her skin, and so the First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, who ardently fought against segregation, resigned all her official D.A.R. duties and advised President Roosevelt to authorise the organisation of this special concert at the Lincoln Memorial. The repercussions of the highly symbolic event were considerable.

Marian Anderson, who was born in 1897 in a poor neighbourhood of Philadelphia (she passed away in 1993 at the age of 96), was prevented from entering a competition because she was a Negro, but her distinguished contralto timbre and her performances of both classical pieces and spirituals were quickly recognised by artists like Toscanini as well as by American and European audiences. Her immense talents would justify her becoming the first Black vocalist to sing at The Met in 1951. In a way, she was the female counterpart of the period’s other exceptional personality, Paul Robeson (1898 – 1976).

Robeson’s father, born a slave, had fled from a South Carolina plantation at the age of 15 before receiving an education in the North and becoming a preacher. His mother, a mulatto, came from a family of Quakers with abolitionist leanings. Paul Robeson was a member of the New York bar, yet quickly abandoned a career as an attorney to become an actor, and he rose to fame both on the stage and in films (he appeared in eleven of them, including Show Boat in 1936). As French saxophonist Raphaël Imbert explains in his book Jazz Supreme – Initiés, Mystiques et prophètes, Paul Robeson was initiated as a “Mason on sight” by a Prince Hall Freemasonry lodge. This honorary American freemason’s title demonstrated that a militant communist artist who was also persona non grata could be considered a brother by every Prince Hall mason “with regard for his work and his actions.” Paul Robeson had defended Spanish Republicans. Nor had he ever concealed his aversion to fascism or his predilection for Communist ideals, and he was also more than committed to the Civil Rights Movement. Such a moral and political stance could only ensure he would be blacklisted during the McCarthy era. As an excellent attorney, Robeson, in accordance with the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, would refuse to disclose his political affiliations. His passport was taken away from him in 1950 and only returned in 1958 after a Supreme Court decision. His return to favour was celebrated by a Carnegie Hall concert that year.

The last years of Robeson’s career were as uneasy as those of Josh White, who lost favour after his appearance in front of the McCarthy Commission, and closeness to the style of folk singers Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston and Burl Ives. Born in South Carolina in 1915 (he died in 1969), Josh White received a very strict religious education. When he was seven, accompanying a group of blind blues singers, he witnessed a lynching and discovered the activities of the Ku Klux Klan, which instilled in him a hatred of the southern states; he forged a political conscience that would become visible in the virulent texts of his songs (and also the way he performed Strange Fruit.) He quickly began making records, and settled in New York, playing in the clubs of Harlem and Greenwich Village. He developed a style that brought southern traditions together with a sophisticated, urban style where his remarkable guitar playing made a great impression. Supported by Eleanor Roosevelt, he was invited to the White House, but his recordings greatly displeased the racist leagues in the South: his records were destroyed in public, his home was burnt to the ground, and the KKK issued his death warrant. But in the North of the Forties he would become the darling of liberals, intellectuals, critics and public alike. It was no surprise to see him acting alongside Paul Robeson in Langston Hughes’ The Man Who Went To War. Yet everything suddenly went sour after his appearance in front of the notorious “House Un-American Activities Committee”. Unlike Paul Robeson, Josh White’s image waned in the same way as that of filmmaker Elia Kazan.

Eleven days after Marian Anderson’s concert, jazz singer Billie Holiday made Strange Fruit immortal, a song that Nina Simone would revive in 1965. Still in the jazz vein, but in his own way, drummer Max Roach continued the fight against segregation with albums like Percussion Bitter Sweet, where the title Garvey’s Ghost appeared as a tribute to the memory of Civil Rights leader Marcus Garvey, who sought exile in England.

Dark suns over Iberia

Troubled waters ran through Spain and Portugal in the 1920’s. Political controversy led to dictatorship in both Portugal, when Antonio Salazar rose to power in 1928, and Spain at the end of the Civil War (1939) under Francisco Franco, el caudillo. The two men had little in common except for a conservative vision of the world and political stances that would exert a dramatic influence over culture.

Salazar, an activist – anti-Communist, Catholic, nationalist (although he did have a corporatist social awareness) – kept a discreet profile. The Estado Novo, the name given to the authoritarian regime he established, was no less than a dictatorship that maintained surveillance over artists, intellectuals and union leaders; Salazar’s rule was notorious for torturing prisoners and censoring the press and artistic performances. Like others in the traditionalist bourgeoisie, Salazar detested the fado genre and its immorality, its lack of respectability and its rejection of rural themes, not to mention the fact that it welcomed proletarian ideas. Right from the beginning of the Thirties, the Salazar regime demanded that fado artists register as such officially, and that they submit their texts to the censors. The Museu do Fado in Lisbon exhibits lyric sheets that bear the stamp “censored”.

Amalia Rodrigues (1920 - 1999), whose singing, talented accompanists and poetic repertoire gave new impetus to the fado genre, wasn’t spared the heavy pressure of those in power, nor criticisms that came from left-wing activists in the Sixties. Alain Oulman, one of her composers and the man who encouraged her to sing the works of poets like David Mourão-Ferreira, Alexander O’Neal and Manuel Alegre, spoke out on her behalf. She had first-hand experience of the PIDE political police, who combed the narrow streets of Lisbon hunting for those who went to listen to her in the “casas de fado” at nightfall, once the curtains were drawn and the tourists had long disappeared. The words of Oulman, a Frenchman born in Portugal in 1928 (and the nephew of the publisher Calmann–Levy), take on full meaning when one learns that in 1966 he was imprisoned and tortured by the PIDE before his expulsion.

In Spain, Franco’s followers wanted to stifle the strong popular impact of flamenco that lay behind the genre’s traditional lyrics. Federico Garcia Lorca and Manuel de Falla had recognised the genre’s vitality and wanted to restore flamenco’s image by integrating its constituent elements into their own compositions, and they launched the first Cante Jondo in Granada in 1922. One should note that the competition saw the sharing of the First Prize between Diego Bermudez Calas, aged 72, who walked sixty miles to compete, and a 13 year-old gypsy named Manuel Ortega Juarez, who was destined to become the first great cantaor in flamenco history; better known as Manolo Caracol, he died accidentally in 1973.

Federico Garcia Lorca was a playwright who managed an itinerant theatrical troupe, and a poet of genius. He was also an excellent pianist and good composer who throughout his life would write flamenco songs and melodies. Like Manuel de Falla, he advocated taking the classical and popular traditions of Spain and projecting them onto a modernist horizon flirting with the avant-garde that he and De Falla had encountered in Paris. Lorca, a homosexual, was reputed for his anti-fascist beliefs in an Andalusia where the dominant oligarchy was at its most violent. Franco’s militia arrested him on August 16, 1936, and put him in front of a firing squad three days later, throwing his corpse into a common grave. And as if that wasn’t enough, the Franco regime banned his works until 1953. The greatest cantaora in flamenco history, the gypsy Niña de Los Peines (Pastora Cruz Pavon, b. 1890, d. 1969) was a friend of Lorca. She paid tribute to him in a concert that took place on August 19, 1937 in Madrid when the capital was still Republican.

Manuel de Falla (b.1876 in Cadiz, d. 1946 in Argentina), was a modest, reserved man of fragile health whom his contemporaries worshipped. The mother of the young cantaora Pastora Imperio initiated him into the codes of flamenco so that he could compose his ballet El Amor Brujo, a work followed in 1917 by El Sombrero de Tres Picos, which he destined for the Ballets Russes of Diaghilev. His Concerto for Harpsichord and Ensemble is a strangely beautiful piece. Falla, a dedicated Republican yet a fervent Catholic, spoke out against the pillaging and burning of churches in a letter to the President of the Republic at the beginning of the Civil War. Courted by the regime, he refused to bend to Franco’s orders and voluntarily went into exile in Argentina, where he died in 1946. The funeral celebrations in Seville Cathedral the following year were nothing more than an attempt to reclaim de Falla’s image.

In France, the wrath of Anastasia

“Madame Anastasie” was the name given by André Gill to a caricature that appeared in 1874 in the pages of the French satirical journal L’Eclipse. The “Madam Anastasia” in question was an old, ugly, bespectacled woman carrying a huge pair of scissors under her arm. Anastasia was also the name given to a system of censorship that France installed by decree on 5 August 1914, effectively gagging the French press… From then on, the Anastasia system’s targets were clearly identified: anti-military songs that had anarchist leanings; texts with sexual connotations expressed in “naughty” language; and any salacious image whose message was politically incorrect.

At the end of the Second World War, French radio, the “RadioDiffusion Française,” set up a so-called “Listening Committee” which divided songs into four categories: those that were authorised; those that could be aired after 10 p.m.; those for broadcast only after midnight; and songs that were banned altogether. Victims of the censors’ wrath included artists like Bobby Lapointe (Embrouille Minet), Léo Ferré (Paris Canaille, Jolie Môme, Merde à Vauban…), Yves Montand (Sanguine, a magnificent song written by Jacques Prévert and Henri Crolla), Georges Brassens (Le Gorille), Juliette Greco (for Chandernagor, the song by Guy Béart), and Magali Noël, for her performance – more rock ’n’ roll than erotic – of the Boris Vian and Alain Goraguer song, Fais-moi mal, Johnny !

But more than the country’s moral order, it would be the songs La Chanson de Craonne and Le Déserteur that remained indelible traces on French memories of the havoc wreaked by censorship on radio and television. Take the sad story of La Chanson de Craonne. It was very much in vogue after the bloody battle of Chemin des Dames in 1917 (also known as the Second Battle of the Aisne), and it had several variants by anonymous songwriters, based on a 1911 melody by Charles Sablon and Raoul Le Peltier (Bonsoir m’amour). The song was a cry of protest, and it was consequently banned by the military High Command for its anti-war message considered as defeatist and subversive (we may remember that French casualties in the battle led to mutinies in the infantry divisions, and more than three thousand soldiers were punished, with 57 executed.)

And in 1954, when the war in Indochina was coming to an end, no-one apart from Mouloudji would care to sing Boris Vian’s song Le Déserteur. Vian would record it himself in May 1955, but his album Chansons possibles sold very few copies. Yet Le Déserteur, in time, would become an iconic song.

Philippe LESAGE

© 2022 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Discographie

Censure - Les musiciens face au pouvoir politique : 1929 - 1962

CD1 : La musique dégénérée selon les nazis

Bela Bartok

Contrast for Violin, Clarinet and Piano SZ 111 (Bela Bartok)

1) Verbunkos (Recruiting Dance) 5’25

2) Pihneö (Relaxation) 4’33

3) Sebes (Fast Dance) 6’54

Bela Bartok (piano) Joseph Szigeti (violon) Benny Goodman (clarinette)

Enregistré les 13 et 14 Mai 1940

78 t Columbia 70 – 362 - D

Benny Goodman

4) Stompin’ At The Savoy (Goodman, Webb, Sampson, Razaf) 3’19

Benny Goodman (clarinette), Lionel Hampton (vibraphone), Teddy Wilson (piano), Gene Krupa (batterie)

Victor 25521 – 2 décembre 1936

Igor Stravinsky

5) Ebony Concerto For Orchestra (Stravinsky) 8’40

3 mouvements : moderato, andante, moderato con moto

Soliste : Woody Herman (clarinette) ; Woody Herman’s Band, directed by Stravinsky

America Columbia 7479 M – 19 août 1946

Alban Berg

6) Lulu – Suite : Adagio (Berg) 9’00

Helga Pilarczyk (soprano), London Symphony Orchestra, directed by Antal Dorati

Mercury 432 006 – 2/ Juin 1961

Arnold Schoenberg

7) Five Pieces for Orchestra opus 16 : mouvement Summer Morning by a Lake (Schoenberg) 3’38

London Symphony Orchestra, directed by Antal Dorati

Mercury 43200 – 2 / 1961

Kurt Weill

L’Opéra de Quat Sous (Bertold Brecht – Kurt Weill)

Sur une idée d’Elisabeth Hauptman et inspiré de « The Three Penny Opera » de John Gay

8) Acte I Ouverture 2’06

9) Acte I Complainte de Mackie 3’04

10) Acte I Chanson nuptiale pour les pauvres gens 1’25

11) Acte I Chansons des canons 2’20

12) Acte I Chant d’amour 1’55

13) Acte I Chanson de Barbara 4’46

14) Acte II Chant d’adieu de Polly 1’50

15) Acte II La ballade de l’esclavage des sens 3’43

16) Acte II Jenny des pirates 4’22

17) Acte II La ballade du souteneur 4’38

18) Acte II La ballade de la vie agréable 2’32

19) Acte III Le chant de la vanité de l’effort humain 2’15

20) Acte III Derniers couplets de la complainte 1’25

Wolfgang Neuss (Moritatsanger), Willy Trenk - Trebish (Herr Peachum), Eric Schellow (Macheath), Lotte Lenya (Jenny), Trude Hesterberg (Frau Peachum), Johanna Von Koczian (Polly Peachum)

Direction : Wilhem Brückner - Ruggeberg ; chœur et orchestre des Sender Freies Berlin

CBS 78279 / 1958

CD2 : Résistance à Staline

Serguei Prokofiev

Sonate pour piano N° 8 en si bémol majeur (Prokofiev)

1) Andante dolce - allegro moderato – andante dolce con prima 15’50

2) Andante Sognando 4’18

3) Vivace – allegro ben marcato - vivace 9’43

Sviatoslav Richter

Enregistré à Londres le 28 juillet 1961

DG 449 744 – 2 / 1962

Dimitri Chostakovitch

String Quartet n° 8 op 110 en ut mineur (Chostakovitch)

4) Largo 4’07

5) Allegro molto 2’43

6) Allegretto 3’50

7) Largo 5’08

8) Largo 3’05

Borodin Quartet (Rotislav Dubrinsky et Yaroslav Alexandrov : violons ; Dimitry Shebalin : alto ; Valentin Berlinsky : violoncelle)

Mercury SR – 90309 / 17 Juin 1962

Dimitri Chostakovitch

Violin Concerto N° 1 in A minor op 99 (Dimitri Chostakovitch)

9) Passaglia 13’28

10) Burlesque 4’48

Dimitri Chostakovitch

Prélude et Fugue N° 24 en ré mineur opus 87 (Chostakovitch)

11) Prélude 4’32

12) Fugue 6’32

Emil Guilels (piano)

Melodya ; enregistré en 1955

CD3 : Paranoïa anti-communiste aux USA, Espagne et Portugal alors que les censeurs français sans humour et moralistes dénoncent aussi l’antimilitarisme

1) Strange Fruit (Allan) 3’06

Billie Holiday (voc), Charlie Shavers (tp), Wynton Kelly (p), Kenny Burrell (g), Aaron Bell (contrebasse)

Verve – Août 1954

2 ) Black Girl (Josh White) 2’58

Josh White (voc et g)

LP The Story Of John Henry

Vogue – MDEKL 9436 – 1958

3 ) Free & Equal Blues (Harburg – Robinson) 3’49

Josh White (voc, g)

Idem 2

4) Ol’Man River (Hammerstein II – Kern) 4’03

Paul Robeson with Victor Young & His Convent Orchestra

BXL 12096 A – 21 juillet 1932

5) Freedom (trad) 1’54

Paul Robeson (voc), Alan Booth (p)

LP At Carnegie Hall – 9 mai 1958

Vanguard Record VCD 72020

6) Monologue From Shakespeare’s Othello 2’44

Paul Robeson (Déclamation)

7) Hold On (arr : Hall Johnson) 2’23

Marian Anderson (voc), Franz Rupp (p)

RCA Victor 101278 -B – 1945

8) Uncle Sam Says (Waring Cuny – Josh White) 2’41

Josh White (voc, g)

QB -1690 – 1941

9) Garvey’s Ghost (Max Roach) 7’52

Booker Little (tp), Julian Priester (tb), Eric Dolphy (as, b-cl, fl), Clifford Jordan (ts), Mal Waldron (p), Art Davis (b), Max Roach (batterie), Carlos « Potato » Valdez (congas), Carlos « Totico » Eugenio (cowbells), Abbey Lincoln (voc)

LP Percussion Bitter Sweet; Impulse ! – Aoùt 1961

10) Asas Fechadas (Macedo – Alain Oulman) 2’51

Amalia Rodrigues (voc), Alain Oulman (p), José Nunes (guitarra), Carlos Motta (viola)

album Busto EMI Valentm de Carvalho – 1960

11) Cais de Outrora (Macedo – Alain Oulman) 3’24

Idem 10

12) Maria Lisboa

(Mourão-Ferreira – Alain Oulman) 2’47

Amalia Rodrigues (voc), José Nunes (guitarra), Castro Motta (viola)

Idem 10

13) Poema Del Cante Jondo (Garcia Lorca) 7’56

Thèmes : Argueros/Sevilla/Saeta/Balcon)

Germaine Montero (voc), Ramon Cueto (g)

Vega P35 M – Ca 1959 / 1960

14) Peribanez (Garcia Lorca) 1’46

Germaine Montero (voc)

15) L’Amour Sorcier (de Falla) 4’50

Mouvement Danse Rituelle du Feu

Ines Rivadeneira (contralto), Orchestre des Concerts de Madrid, direction Jesus Arambarri

Erato STU 70092 – 1962

16) La Chanson de Craonne (anonyme) 3’33

Eric Amado (voc)

Le Chant du Monde : PM1 025 – 1952

17) Le Déserteur (Harold B Berg – Boris Vian) 3’28

Boris Vian (voc)

LP Chansons « Possibles » et « Impossibles »

Philips – 1956

18) Le Gorille (Georges Brassens) 3’16

Georges Brassens (voc, g)

LP La Mauvaise Réputation (édité auparavant sous le titre : « Les chansons poétiques (et souvent paillardes) de Georges Brassens » – 33 t/ 25 cm Polydor 530 011 – 1953

19) Fais-Moi Mal, Johnny

(Boris Vian – Alain Goraguer) 2’21

Magali Noël (voc) et Alain Goraguer et son Ensemble

Philips 45 t simple 432 131 NE – 1956

20) Sanguine (Jacques Prévert – Henri Crolla) 2’43

Yves Montand (voc) Orchestration Hubert Rostaing, Orchestre sous la direction de Bob Castella

LP Montand Chante Prévert

Philips 836 681-2 – 1960