- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

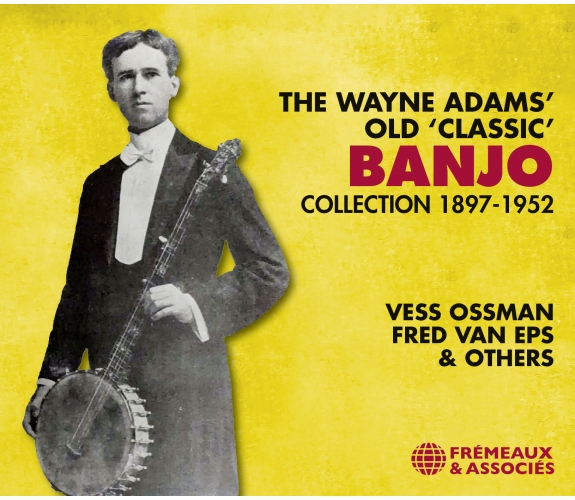

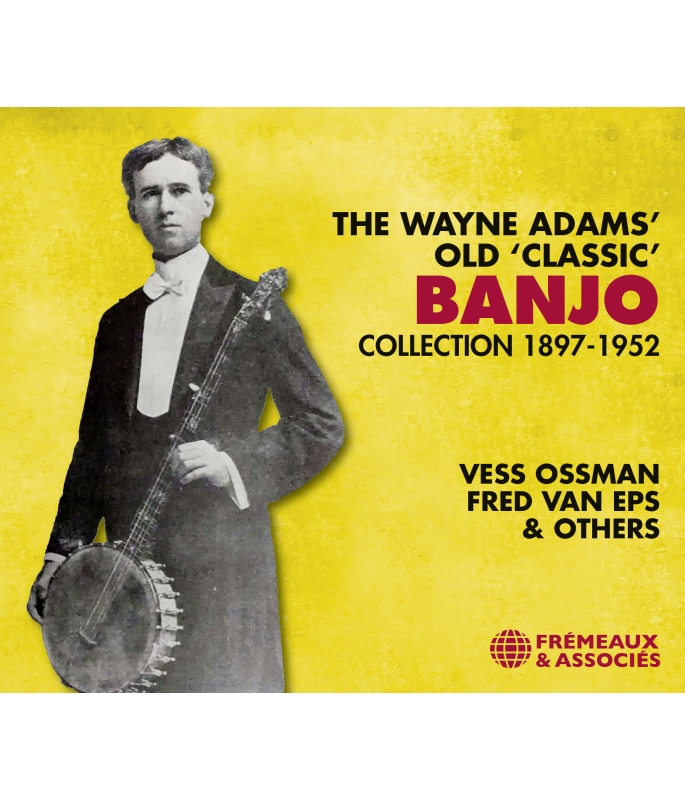

VARIOUS ARTISTS

Ref.: FA5816

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 37 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

- -

- -

Prepared by Gérard De Smaele, an eminent five-string banjo specialist, this anthology clears the field in revealing older recordings by the great forgotten modernizers of the so-called “classical” banjo, among them Fred Van Eps and Vess Ossman. The selection here unveils a major chapter in the history of this famous instrument, some of whose technical aspects are still in evidence today in modern bluegrass. Drawn from sources collected by Wayne Adams (Toronto, 1929-2013), this is a brand new historical exploration of the repertoire of the North American continent’s popular instrument of reference.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CD 1. VESS OSSMAN: BLAZE AWAY (1900) • A BUNCH OF RAGS (1910) • CALIFORNIA DANCE (1903) • COLORED MAJOR (1908) • COON BAND CONTEST (1901) • EL CAPITAN MARCH (1902) • FLORIDA RAG (1908) • FUN IN A BARBER SHOP (1908) • INVINCIBLE EAGLE MARCH (1909) • MAPLE LEAF RAG (1908) • A MEDLEY OF OLD TIMERS (1900) • THE MOOSE MARCH (1909) • THE MOSQUITO PARADE (1901) • MOTOR MARCH (1906) • PEACEFUL HENRY (1903) • PERSIAN LAMB RAG (1911) • PETER PIPER (1906) • RUSTY RAG MEDLEY (1901) • SILVER HEELS (1904) • SAINT LOUIS TICKLE (1908) • SUNFLOWER DANCE (1906) • TURKEY IN THE STRAW MEDLEY (1909) • WHOA BILL (1902) • WILLIAM TELL OVERTURE (1897) • YANKEE DOODLE (1900).

CD 2. FRED VAN EPS: BOLERO (1952) • CHINESE PICNIC & ORIENTAL DANCE (1923) • COCOANUT DANCE (1923) • CUPID’S ARROW (1917) • DALY’S REEL RAG (1916) • DIXIE MEDLEY (1930) • FROLIC OF THE COONS (1915) • GRACE AND BEAUTY (1924) • I’M ALWAYS CHASING RAINBOWS (1918) • INFANTA’S MARCH (1913) • MAURICE TANGO (1912) • THE NEW GAIETY (1952) • MY SUMURUN GIRL (1912) • NOLA (1952) • PEARL OF THE HAREM (1911) • PERSIFLAGE (1925) • RAGGIN’ THE SCALE (1916) • A RAGTIME EPISODE (1911) • RAGTIME ORIOLE (1924) • RED PEPPER RAG (1911) • RONDO CAPRICE (1952) • SING LING TING (1918) • SMILER RAG (1914) • TAMBOURINES AND ORANGES (1952) • TEASING THE CAT (1916), • WHIPPED CREAM (1913) • THE WHITE WASH MAN (1912).

CD 3. OTHERS: FRED BACON / MASSA’S IN THE COLD COLD GROUND (1917) • FRED BACON / MEDLEY OF SOUTHERN AIRS (MY OLD KENTUCKY HOME / DIXIE / OLD FOLKS AT HOME) / (1920) • BILL BOWEN / OLD STONE HOUSE (CA. 1950) • BILL BOWEN / VALSE DE CONCERT (CA. 1950) • FRANK BRADBURY / DANCE OF THE HOURS (CA. 1950) • FRANK BRADBURY / DONKEY LAUGH (CA. 1950) • H.C. BROWN / CLIMBING UP THE GOLDEN STAIRS (1917) • ALFRED CAMMEYER / CHINESE PATROL / (1912) • BERT EARLE / THE BACCHANAL RAG (UNKNOWN) • ALFRED FARLAND / CARNIVAL OF VENICE (1917) • PARKE HUNTER / DIXIE GIRL (1903) • E. JONES / POMPADOUR (CA.1925) • E JONES. / NIGGER TOWN (CA.1925) • ALFRED KIRBY / HEATHER BLOOM (UNKNOWN) • ALEXANDER MAGHEE / JOLLY DARKIES / (CA. 1950) • JOE MORLEY / JAPANESE PATROL (1918) • OLLY OAKLEY - BOLERO (1907) • OLLY OAKLEY / A BANJO ODDITY (UNKNOWN) • OLLY OAKLEY / THE PALLADIUM MARCH (1923) • WILL PEPPER / DINKY’S PATROL (1904) • JOHN PIDOUX / A PLANTATION EPISODE / (1919) • TED SHAWNEE / BLACK AND WHITE RAG – (CA. 1950) • SHIRLEY SPAULDING / A FOOTLIGHT FAVORITE (1922) • SIDNEY TURNER / ADANTE ET WALTZ (1913) • SIDNEY TURNER & CLIFFORD ESSEX / A BUNCH OF RAGS (1914).

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Blaze AwayVess OssmanVess Ossman00:03:151900

-

2A Bunch Of RagsVess OssmanTraditionnel00:02:201910

-

3California DanceVess OssmanGregory George00:01:401903

-

4Colored MajorVess OssmanRobert Stern Henry00:02:371908

-

5Coon Band ContestVess OssmanArthur Pryor00:02:301901

-

6El Capitan MarchVess OssmanJohn Philip Sousa00:02:261902

-

7Florida RagVess OssmanGeo Lowry00:02:291908

-

8Fun In A Barber ShopVess OssmanJense Winne00:02:511908

-

9Invincible Eagle MarchVess OssmanJohn Philip Sousa00:02:591909

-

10Maple Leaf RagVess OssmanScott Joplin00:02:421908

-

11A Medley Of Old TimersVess OssmanVess Ossman00:02:271900

-

12The Moose MarchVess OssmanFlath00:02:541909

-

13The Mosquito ParadeVess OssmanHoward Whitney00:02:311901

-

14Motor MarchVess OssmanGeorge Rosey00:03:011906

-

15Peaceful HenryVess OssmanKelly Harry00:02:381903

-

16Persian Lamb RagVess OssmanPercy Wenrich00:02:211911

-

17Peter PiperVess OssmanRobert Stern Henry00:02:311906

-

18Rusty Rag MedleyVess OssmanVess Ossman00:02:351901

-

19Silver HeelsVess OssmanNeil Moret00:02:451904

-

20Saint Louis TickleVess OssmanSeymore00:03:031908

-

21Sunflower DanceVess OssmanVess Ossman00:02:021906

-

22Turkey In The Straw MedleyVess OssmanVess Ossman00:02:211909

-

23Whoa BillVess OssmanHarry Von Tilzer00:02:161902

-

24William Tell OvertureVess OssmanGiacomo Rossini00:02:441897

-

25Yankee DoodleVess OssmanTraditionnel00:02:231900

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1BoleroFred Van EpsFred Van Eps00:02:181952

-

2Chinese Picnic , Oriental DanceFred Van EpsFred Van Eps00:03:041923

-

3Cocoanut DanceFred Van EpsAndrew Hermann00:03:081923

-

4Cupid's ArrowFred Van EpsPaul Eno00:02:161917

-

5Daly's Reel RagFred Van EpsDaly00:02:571916

-

6Dixie MedleyFred Van EpsTraditionnel00:02:251930

-

7Frolic Of The CoonsFred Van EpsFrank Gurney00:02:311915

-

8Grace And BeautyFred Van EpsJames Scott00:03:371924

-

9I'm Always Chasing RainbowsFred Van EpsCarroll00:02:481918

-

10Infanta's MarchFred Van EpsGeorge Gregory00:04:221913

-

11Maurice TangoFred Van EpsHein00:02:461912

-

12The New GaietyFred Van EpsDurandeau00:03:301952

-

13My Sumurun GirlFred Van EpsTraditionnel00:04:161912

-

14NolaFred Van EpsFelix Arndt00:02:231952

-

15Pearl Of The HaremFred Van EpsHenry Frantzen00:02:431911

-

16PersiflageFred Van EpsWalter Francis00:03:001925

-

17Raggin' The ScaleFred Van EpsEdward Claypoole00:02:451916

-

18A Ragtime EpisodeFred Van EpsPaul Eno00:02:491911

-

19Ragtime OrioleFred Van EpsJames Scott00:03:221924

-

20Red Pepper RagFred Van EpsHenry Lodge00:02:151911

-

21Rondo CapriceFred Van EpsSilverberg00:02:221952

-

22Sing Ling TingFred Van EpsGeorge Colb00:02:371918

-

23Smiler RagFred Van EpsPercy Wenrich00:03:051914

-

24Tambourines And OrangesFred Van EpsKlickmann00:02:501952

-

25Teasing The CatFred Van EpsCharles Johnson00:03:021916

-

26Whipped CreamFred Van EpsPercy Wenrich00:03:011913

-

27The White Wash ManFred Van EpsSchwartz.00:02:561912

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Massa's In The Cold Cold GroundFred BaconStephen Foster00:03:321917

-

2Medley Of Southern Airs (My Old Kentucky Home Dixie Old)Fred BaconStephen Foster00:03:051920

-

3Old Stone HouseBill BowenBill Bowen00:02:261950

-

4Valse De ConcertBill BowenBill Bowen00:03:301950

-

5Dance Of The HoursFrank BradburyAmilcare Poncielli00:04:051950

-

6Donkey LaughFrank BradburyJoe Morley00:02:221950

-

7Climbing Up The Golden StairsHarry BrownHeiser00:02:511917

-

8Chinese PatrolAlfred CammeyerCammeyer00:02:581912

-

9The Bacchanal RagBert EarleLouis Hirch00:02:341912

-

10Carnival Of VeniceAlfred FarlandJulius Benedict00:04:011917

-

11Dixie GirlParke HunterJames Bodewalt Lampe00:02:351903

-

12PompadourErnst JonesJoe Morley00:02:471925

-

13Nigger TownErnst JonesJoe Morley00:02:381925

-

14Heather BloomAlfred KirbyAlfred Kirby00:02:351925

-

15Jolly DarkiesAlexander MagheeJolly Darkies00:04:191950

-

16Japanese PatrolJoe MorleyJoe Morley00:02:231918

-

17BoleroOlly OakleyAlfred Cammeyer00:03:071907

-

18Banjo OddityOlly OakleyJoe Morley00:03:071907

-

19The Palladium MarchOlly OakleyJoe Morley00:02:301923

-

20Dinky's PatrolWill PepperAlf Newton00:03:011904

-

21A Plantation EpisodeJohn PidouxEmile Grimshaw00:02:521919

-

22Black And White RagTed ShawneeGeorge Botsford00:02:221919

-

23A Footlight FavoriteShirley SpauldingEmile Grimshaw00:03:291922

-

24Adante Et WaltzSidney TurnerAlfred Cammeyer00:02:191913

-

25A Bunch Of RagsSidney TurnerVess Ossman00:02:221914

"banjo is the greatest of musical instruments when it is played well […] In tone quality it is very much like the harp, and its flexibility of playing is unexcelled, for in the hands of a skilled player it is as good for classical music as for dance tunes. It is the only original American instrument, and is coming into its own as the greatest of them all.”

Frederick Bacon, ca. 1900.

THE OLD CLASSIC BANJO

The oldest recordings of the five-string banjo, known to date, would have been made in 1889 for the Edison Laboratory by Bill Lyle, whose stage name was William Lomas (1859-1941). In the same year, one of them was exhibited among other cylinders presented to the public at the Universal Exhibition in Paris.

The niece of this now forgotten musician had married the son of John Henry Buckbee, the founder of what was reckoned in the last third of the 19th century to be the largest banjo factory in the world. In all likelihood, Lomas had his instruments made by Buckbee, before they were distributed by Bruno & Son, a leading wholesaler of musical instruments.

If the once famous names of the Buckleys, Frank Converse, the Dobson brothers, Samuel Swain Stewart and others such as Vess Ossman, Fred Van Eps, Alfred Farland or Frederick Bacon… are nowadays forgotten by the general public, the so-called ‘classic’ banjo still plays a major part in the history of the five-string banjo, and certain aspects of the playing technique are still evident even in modern bluegrass. From the end of the American Civil War and for more than half a century afterwards, this classic style prevailed both in the United States and in England. It even seems that it has spread a little in France, too. It was during this time that the instrument was perfected, ultimately leading to a physical design that remains the same today. Its eclectic repertoire, comprising a mixture of traditional melodies and more elaborate classical music, is surprisingly diverse: dedicated compositions, adaptations of purely classic works, rags and other popular tunes of the time. This body of work shows that, in addition to its traditional (folk) repertoire, the banjo offers a whole range of other possibilities.

The initial attempts at the first wave of banjo recording only came to fruition around the 1900s but it was still this ‘old style’ that led the way, a good 20 years ahead of commercial country music.

At the same time, since the end of the 19th century there have also been various revivals of interest in traditional music from the South of the United States, at the heart of which the five-string banjo - recognised as ‘America’s Instrument’ - has a privileged place. Indeed, what else but the banjo - without underestimating the importance of jazz- could better symbolise the ‘melting pot’ that characterises the American identity? After a period of indifference towards the ‘5-string’, New York became at the end of the 1950s and through the following decade, the epicentre of a great folk revival, whose breadth, duration and international scope would largely exceed those of the earlier movements. The banjo would be one of its main symbols.

Its very diversity makes the history of the five-string banjo particularly rich: reflecting a complex adventure which is the result of the constant migration that has been shaking up the Western world since the 16th century. Whilst the instrument finds its distant origins in obscure regions of Africa, its repertoire is largely inspired by Europe and ends up with a complete blend of influences in the new world. At the end of this journey, we clearly discover the full range of all African-American music, which so marked the 20th century. This fundamental contribution testifies to the importance and international reach of the banjo. But the real reason the banjo made its mark is that it was able to inspire images d’Epinal (albeit romantic and imaginary both from the southern states as well as from Africa) and at the same time as creating a contagious energy in the listener.

“When you want genuine music - music that will come right home to you like a bad quarter, suffuse your system like strychnine whisky, go right through you like Brandreth’s pills, ramify your whole constitution like the measles, and break out on your hide like the pin-feather pimples on a picked goose, -- when you want all this, just smash your piano, and invoke the glory-beaming banjo!” [Mark Twain, “Enthusiastic Eloquence,”

San Francisco Dramatic Chronicle, 23 June 1865.]

But, far from being restricted by its history, the banjo will also prove to be an instrument in its own right. While it spreads the joie de vivre, it also has genuine appeal for each and every different human soul.

This is the “banjo!”

The basic process is ancient and its scope is universal. The body of a banjo is made up of a circular structure on which a membrane is stretched. The acoustic properties of such a design produce an invigorating sound which lifts and touches people’s spirits whoever they are. In this way, the banjo grabbed everyone’s imagination, creating its own myths and clichés, sometimes defying historical, even musicological reality. Slaves from plantations in the Southern States, American cowboys, Route 66, commercial country music, emerging jazz...without forgetting the ancient musical traditions of the Southern Appalachian Mountains, bluegrass...will make up its most fertile soil.

For those in the know, however, the year 2019 will be marked by the celebration of the centenary of the birth of Pete Seeger (1919-2014), whom the Smithsonian Institution will honour with the publication of a beautiful book, accompanied by a set of 6 CDs. It is, at last, a proper recognition of the man who has enriched the catalogue of the Folkways house with countless recordings. Folkways was founded more than 70 years ago in New York by Moses Asch (1905-1986), father of the non-commercial label Smithsonian/Folkways, and is an eminent, official institution of which the United States can be proud. Pete Seeger was an immense banjoist, responsible with Earl Scruggs (1924-2012) for the new development and revival of the five-string banjo. Let’s not allow the press’s somewhat shallow portrayal of the banjo to make us forget the heroic stance of this artist who, disturbed by McCarthyism in the 1950s, accompanied Pastor Martin Luther King in the march towards Washington in 1963. In the wake of the great folk revival of the 1960s, how many young Americans, following the example of the one who showed them the way (well before the young Greta Thunberg) have, banjo in hand, challenged the society of their time?

In bringing musical elements from the west coast of Africa to the new world, sadly the banjo begins its history with the deportation of millions of slaves. The minstrel show, the Jim Crow laws and segregation are there to remind us that the roots of this rich instrument, which spread across all kinds of musical genres, are embedded in this dark underworld. The international impact of folk music or black music will not let us forget it. But the five-string banjo is also a reflection of the progress of American society in all its guises.

The story of the banjo is never-ending and as complex as the human soul, incorporating a mixture of both good and bad. The stereotypical image of the banjo does not do it justice, but hopefully this brief presentation will reveal a little more and encourage the public to reconnect with its history and discover more about this astonishing stringed instrument and both its prestigious as well as its more down-to-earth authentic players.

***

In the 1830s, it was as part of the minstrel show that white musicians made-up in coal black, ‘Europeanised’ the primitive instrument of African-Americans and appropriated the banjo. The five string banjo then became the starting point from which a whole musical evolution would follow. Its most elaborate and most recent form is that of the bluegrass banjo, a hybrid instrument whose body is the same as that of the tenor and plectrum banjos, made in the inter-war period for jazz orchestras and dance music, which have 4 strings of equal length. Meanwhile, from the end of the American Civil War to the First World War, it evolved into a concert and lounge instrument, derived from the classical guitar. At the same time, in the Southern States, it became a pillar of ‘country music’, a musical tradition with deep Anglo-Saxon roots, given pride of place during the great folk revival of the 1960s.

The so-called ‘classic banjo’.

And so it was white musicians, who from the first half of the 19th century developed and marketed the emblematic instrument of slaves in the South of the United States. They brought profound modifications to the old banjo gourd, fretless and four strings, the highest pitched of which is shorter than the others and found in plantations. A low string was added by Joel Sweeney (1810-1860), while a box made from a bent wooden hoop gave it more rigidity. It was William Espérance Boucher (1822-1899), luthier and manufacturer of drums of German origin who added an adjustable tension system to the skin. His workshop was located in Baltimore, Maryland, a thriving commercial hub and an obligatory crossing point for the minstrel show troops. Initially, their music was a kind of Africanisation of Irish tunes, but at the same time German and even Italian. Although this was eventually shown in methods and collections written in classical notation, the style of play is mainly characterised by hitting the strings with the back of the index fingernail whilst the thumb is used for the chanterelle [a drone string] (as well as the other strings, except the first). This is a particular playing technique, directly linked to the African origins of the banjo. The genre was a resounding success, even in England and the rest of Europe. It left a lasting imprint on traditional rural music from the South States of America.

After the glory years preceding the Civil War, new musicians and luthiers began to see alternatives to this practice, which was considered unrefined and manifestly disrespectful towards black people. After some experimentations (flush frets, position markers, six- and seven-string banjos, always with a chanterelle) and a transition period, a second style came to replace that of the minstrel show: that of the so-called ‘classic’ banjo. It was to extend over a period of fifty years and have a decisive impact on both the playing technique and construction of the modern five-string banjo. This classic banjo, or finger-style - we also sometimes speak of orthodox style, parlour banjo and concert style - was derived from the classical guitar and is radically different from minstrel style (stroke style or banjo style) and other various traditional playing techniques.

- The strings are plucked as in classical guitar, with the thumb and fingers (most often the thumb, index and middle fingers, but also the ring finger or even the little finger);

- The music is always written in classical musical notation (thus departing from the oral transmission), while the compositions come from musicians trained at academic schools;

- The usual accompaniment is a second banjo or piano, as well as other contemporary instruments, and no longer the violin (fiddle)

- Most of the pieces played are instrumentals

A fifth string!

It is initially the timbre of the banjo that catches the public’s attention, with its acoustic sound created by a membrane stretched over a round body. The average listener has no idea of the number of different configurations possible in a banjo: all kinds of necks borrowed from various instruments (guitar, mandolin, ukulele, etc.); a body opened or enclosed by a resonator; metallic, gut, silk or nylon strings; played with a plectrum or with fingers, nails, metal picks. If we focus on the five-string banjo - the regular banjo - it is because it is of particular musical importance. The presence of a fifth string shorter than the others, next to the lowest string, harks back to its African origins and has led to various playing techniques which are specific to it. The five-string banjo is also the only one to end up fretless. In the traditional music of the South of the United States, these playing techniques allow the simultaneous production of a melody, a rhythm and a drone (5th string). For certain keys - and to adapt to that of the tessitura of the voice or the violin – the player needs to have recourse to a whole series of tunings and possibly also the capo.

The so-called ‘classic’ banjo relies on other elements: the fifth string gives an opportunity to pluck an open string to allow the player to more easily change the left-hand position. Only one tuning is used in this style, with a single variant for the bass string. The ideal accompaniment is no longer the violin, but the piano, from which the banjo derives much of its musical development. Compositions are often written for two, even several instruments. A family of five-string banjos was developed by the manufacturer SS Stewart: regular banjo, banjeaurine, piccolo banjo, bass or cello banjo, to form ensembles that proliferated around 1880-1900, before the rise of the recording industry, difficult to record and for which we have no period recordings.

The first recordings in history.

It was around 1890-1920 that the public really had access to the first recorded music, mainly on cylinders marketed by Thomas Edison, as well as by other competing companies, such as the Columbia Record Co. Flat discs with horizontal engraving by Emile Berliner (1851-1929) appeared in 1894, but the cylinders were not abandoned until the 1920s. The introduction and standardisation of electrical processes in the recordings was a technology that would shake up the music industry. Until then, the first decades had been marked by the exclusive use of acoustic and mechanical processes, both for recording and for restoration. Reading devices could also be used for recording the backing, which means that Edison’s machines also continued to be used until the 1950s as dictaphones in offices. At the outset, the problem of duplicating the original recordings had not yet been resolved. The musicians of the first era were then forced to replay the same tunes tirelessly in front of an alignment of acoustic horns, each time producing a small series of cylinders, which could be significantly different over a number of takes. This still experimental period of the first acoustic recordings is also marked by the diversity of components: the raw material used in the composition of the cylinders (vegetable waxes and other components), the number of grooves (tracks) per inch (TPI), the speed of rotation (RPM), the length of the cylinder, the reading time (varying from 2 to 4 minutes). For better quality and to be able to amplify the sound, cylinders of larger diameter were also manufactured. The ‘Concerts Records’ from Edison and the ‘Graphophones Grand Records’ from Columbia, have a diameter of 5 inches and both belong to the family of ‘brown wax cylinders’ which were fragile to handle. All this required adequate reading devices and needles. For this reason, references to the records should include the detail of the type of cylinder or even disc present. It should always be taken into account when reading that the use of an unsuitable needle or an inadequate speed can ruin the recording, already fragile from the start. Brown wax, Concert, Edison Gold Molded, Edison Blue Amberol, Columbia cylinder, Pathé cylinder…are labels printed on the protective packaging of the cylinders. They tell us about their specific characteristics, possibly their fragility and the limits of their sound quality.

Among these first record productions, traditional music from the United States is relatively underrepresented. Although there are some notable exceptions, the collections of the Library of Congress and the recording campaigns of commercial firms in rural America did not really begin until later, in the 1920s. The acoustic qualities of the classical banjo - flourishing music in the big cities of the North East - lent themselves admirably to this emerging technology. In the studios, Vess Ossman 1868-1923) and Fred Van Eps (1878-1960) were the great representatives. For their time, their output was enormous.

In the 21st century, we no longer have any idea of the extent of this phenomenon: a large-scale production of instruments, thousands of musical scores; several hundred collections, learning methods and didactic works; tons of cylinders; many specialist journals, etc. Although this trend runs out of steam in the United States after the First World War, it continues in England with the tenor banjo, and the plectrum - a five-string banjo with the fifth string amputated and played with the plectrum - also ends up becoming the most popular.

Effects of the “classic banjo” on traditional music from the South.

By its very nature, the five-string banjo is an instrument far removed from the world of classical music. Although the minstrel style made extensive use of musical notation, it is clear that in rural areas of the South, the playing techniques were all transmitted orally. The publication in 1948 of How to Play the 5-String Banjo (the particularly influential Pete Seeger method), was the first of its kind and came before the great folk revival. Before this, tablature - also used for the lute - had remained practically unknown. In the 1920s, rural musicians such as Charlie Poole (1892-1931) were exposed to the classic banjo. Ultimately, this playing technique was to be significant in the birth of the three-finger bluegrass style developed by Earl Scruggs (1924-2012) from the end of the 1930s, and which was to prevail throughout the rest of the century. Although single string style, developed by virtuoso Don Reno (1927-1984), probably derives from flat picking (a playing technique used in folk guitar) it is reminiscent of the classic banjo. In general, from the 1960s, the bluegrass banjo would evolve in the direction of a more melodic approach, partially inspired by classic banjoists, somewhat brought to light by the activities of the American Banjo Fraternity (ABF).

The ABF was organised in 1948 by a group of former professional musicians such as Fred Van Eps, Bill Bowen (1880-1963) and Alfred Farland (1864-1954), still alive at the time, and eager to transmit their know-how. The classic banjo had been overshadowed by dance music but had partly survived in England. The Banjo-Mandolin-Guitar Magazine (BMG), founded in London by Clifford Essex in 1903, survived until 2020. Pete Seeger, whose prestigious ancestors could have predisposed him to the practice of classical music was a member of ABF in the 1950s and was inspired by these influences for the construction of his Goofing’Off Suite (Folkways Records, FA2045, 1955), taking up themes from Bach, Beethoven, Grieg and Stravinsky.

In the 1960s, Paul Cadwell (1889-1983), a lawyer trained at Harvard University, living in New Jersey, but also a keen classic banjoist who loved the old school, joined the ‘folkies’ of the ‘time. He was a guest of Pete Seeger in Rainbow Quest, his television show, where he shared the airtime with bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins and singer Hedy West. He was then to be found at the Philadelphia Folk Festival, founded in 1957, surrounded by influential folk groups of the time.

Cadwell, little concerned with the fact that young musicians used metal strings and fingerpicks, was welcomed by the young ‘revivalists’. He was to inspire important ‘folk’ banjoists of the new generation, such as Billy Faier (1930-2016) and bluegrass players such as Roger Sprung (b. 1930) or Bill Keith (1939-2015). Although nowadays the classic banjo may seem somewhat outdated, even the most progressive of our contemporary banjoists, include in their training many elements specific to the playing techniques of the classic banjo. Many contemporary banjoists have experimented with this technical approach, practising scales and becoming familiar with music theory, which is not the case with traditional musicians.

From the end of the 19th century to the first decade of the 20th century, banjo making had known its first golden age. Many of the best instruments were produced in Philadelphia, Boston, and also in New York or Chicago, for classic banjoists using gut strings.

At the start of the folk revival of the 1950s there were hardly any manufacturers of five string banjos in the United States. New players used classic old instruments, as they had in the early days of Country Music in the years 1920-30. These new practitioners used metal strings, sometimes destroying the neck of a banjo which was built for strings with less tension.

Subsequently, many luthiers made their appearance, referring to Fairbanks, Cole, Vega...as well as Dobson, S.S. Stewart, Orpheum, Bacon, who led the banjo to its final form.

Nowadays, classical banjo enthusiasts still favour these same instruments: Farland, Washburn, Van Eps, Bacon & Day...while being receptive to the old English brands which were also very numerous: Abbott, Cammeyer, Temlett, Clifford Essex, Weaver, Windsor, Dallas...

Few contemporary musicians have devoted themselves to the pursuit of the classic banjo. Disc production tends to be very limited and there are only occasional concerts. Béla Fleck, although not restricted to the classic genre, remains undoubtedly the best known of them. It’s an unprofitable exercise in terms of popularity and musical career, but which remains the most demanding and for which we will remember only a few names among our contemporaries. In England, the challenge has been picked up by William Ball, Derek Lillywhite and Chris Sands, one of Tarrant’s Bailey Jr’s last students.

***

In recent decades we have witnessed a new golden age in five-string banjo-making, which is reminiscent of the profusion of luthiers who worked at the end of 19th century and early twentieth. However, contemporary interpreters of the classical style generally prefer to turn to old, so-called ‘original’ instruments. Today a good many of them were strung with metal strings for use in old time music; but it’s with nylon strings - natural gut or synthetic - that our contempory classic players - at least the purists - use them most often, although not always. They are most often open-backed, without a resonator; often made with a veal or goat parchment head. The major brands are those of Dobson, S.S. Stewart, Cole, Fairbanks –as well as Cole & Fairbanks-, Farland, Bacon, Bacon & Day, Vega. As the style has enjoyed immense popularity in England, it is not surprising to find English banjos on the current scene. Temlett, Turner, Weaver, Clifford Essex and also Cammeyer are brands very popular with amateurs. Cammeyer, born in Brooklyn, New York, was the propagator of the zither banjo in which the end of the fifth string is not attached on the left side of the neck, but of the peghead. This string then feeds through a narrow tunnel and reappears at the level of the fretboard. We refer to this English peculiarity as a tunnelled fifth string.

Founded in the 1940s, the ABF continues to perpetuate the repertoire and traditions of the classic banjo. From the start, this association has organised meetings between amateurs and published The Five-Stringer, a periodical which was edited by Elias and Madeleine Kaufman from 1973 to 2017. Dr. Kaufman, historian and collector, has written articles for this review that remain essential references. Joel and Aurelia Hooks are currently in charge of this publication. More recently, the Englishman Ian Holloway created in England an important website making the most of the recent possibilities offered by digitalisation: Classic Banjo Ning. (https://classic-banjo.ning.com/). Along with the publication of the ABF, amateur banjoists consult these two sources the most.

Gérard De Smaele

English Adaptation: David Cotton (Editor of the B.M.G. Mag.)

Extensive liner notes on www.fremeaux.com

© 2022 Frémeaux & Associés

DISCOGRAPHY

THE OLD ‘CLASSIC’ BANJO:

AN INSIGHT INTO THE WAYNE ADAMS’ OLD ‘CLASSIC’ BANJO COLLECTION. 18971952

CD 1. VESS OSSMAN.

1. Blaze Away (Ossman-Farmer) / Abe Holzmann / Victor-Monarch, 1900: 3’15

2. A Bunch of Rags / arr. Vess Ossman, Victor, 1910: 2’20

3. California Dance / George Gregory / Zonophone, 1903: 1’40

4. Colored Major / S.R. Henry / Harmony, 1908: 2’37

5. Coon Band Contest / Arthur Pryor / Lakeside, 1901: 2’30

6. El Capitan March / John Philip Sousa / Columbia, 1902: 2’26

7. Florida Rag / Geo L. Lowry / Columbia, 1908: 2’29

8. Fun in a Barber Shop / Jense M. Winne / Victor, 1908: 2’51

9. Invincible Eagle March / John Philip Sousa / Standard, 1909: 2’59

10. Maple Leaf Rag / Scott Joplin / Standard, 1908: 2’42

11. A Medley of Old Timers / arr. Vess Ossman / Victor-Monarch, 1900: 2’27

12. The Moose March / Flath / Harmony, 1909: 2’54

13. The Mosquito Parade / Howard Whitney / Columbia, 1901: 2’31

14. Motor March / George Rosey / Harmony, 1906: 3’01

15. Peaceful Henry / E. Harry Kelly / Columbia, 1903: 2’38

16. Persian Lamb Rag / Percy Wenrich / Victor, 1911: 2’21

17. Peter Piper / S.R. Henry / Victor 4541, 1906: 2’31

18. Rusty Rag Medley / arr. Vess Ossman / Columbia, 1901: 2’35

19. Silver Heels / Neil Moret / Berliner, 1904: 2’45

20. Saint Louis Tickle / Seymore / Berliner, 1908: 3’03

21. Sunflower Dance / Vess Ossman / Imperial, 1906: 2’02

22. Turkey in the Straw Medley / arr. Vess Ossman / Berliner, 1909: 2’21

23. Whoa Bill / Harry Von Tilzer / Columbia, 1902: 2’16

24. William Tell Overture / Rossini / Columbia, 1897: 2’44

25. Yankee Doodle / arr. Levy / Victor-Monarch, 1900: 2’23

CD 2. FRED VAN EPS.

1. Bolero / Fred Van Eps / Fred Van Eps Lab., 1952: 2’18

2. Chinese Picnic & Oriental Dance / Herbert / Edison, 1923: 3’04

3. Cocoanut Dance / Andrew Hermann / Edison, 1923: 3’08

4. Cupid’s Arrow / Paul Eno / Emerson, 1917: 2’16

5. Daly’s Reel Rag (Fred Van Eps Trio) / Daly / Columbia, 1916: 2’57

6. Dixie Medley / arr. Fred Van Eps / Brunswick, 1930: 2’25

7. Frolic of the Coons / Frank Gurney / Berliner 1915: 2’31

8. Grace and Beauty / James Scott / Edison, 1924: 3’37

9. I’m Always Chasing Rainbows / Carroll / Berliner, 1918: 2’48

10. Infanta’s March / George Gregory / Edison, 1913: 4’22

11. Maurice Tango / Hein / Berliner 1912: 2’46

12. The New Gaiety / Durandeau / Fred Van Eps Lab., 1952: 3’30

13. My Sumurun Girl / not identified / Edison, 1912: 4’16

14. Nola / Felix Arndt / Fred Van Eps Lab., 1952: 2’23

15. Pearl of the Harem / Frantzen / Berliner 1911: 2’43

16. Persiflage / Francis / Columbia, 1925: 3’00

17. Raggin’ the Scale / Claypoole / Berliner, 1916: 2’45

18. A Ragtime Episode / Paul Eno / Victor, 1911: 2’49

19. Ragtime Oriole / James Scott / Edison 1924: 3’22

20. Red Pepper Rag / Lodge / Victor, 1911: 2’15

21. Rondo Caprice / Silverberg / Fred Van Eps Lab., 1952: 2’22

22. Sing Ling Ting / Colb / Emerson, 1918: 2’37

23. Smiler Rag / Percy Wenrich / Berliner, 1914: 3’05

24. Tambourines and Oranges / Klickmann / Fred Van Eps Lab., 1952: 2’50

25. Teasing the Cat / Johnson / Victor,1916: 3’02

26. Whipped Cream / Percy Wenrich / Diamond, 1913: 3’01

27. The White Wash Man / Schwartz / Columbia, 1912: 2’56

CD 3. AUTRES.

1. BACON Fred / Massa’s in the Cold Cold Ground / Stephen Foster / Edison, 1917: 3’32

2. BACON Fred / Medley of Southern Airs (My old Kentucky home / Dixie / Old folks at home) / Stephen Foster / Edison, 1920: 3’05

3. BOWEN Bill / Old Stone House / Bill Bowen / recorded at a New Rochelle concert, ca. 1950 (Americana), ca. 1950: 2’26

4. BOWEN Bill / Valse de Concert / (ca. 1950), 3’30

5. BRADBURY Frank / Dance of the Hours / Amilcare Poncielli, arr. F. Bradbury / - , ca. 1950 (Americana): 4’05

6. BRADBURY Frank / Donkey Laugh / Joe Morley / ca. 1950 (Americana): 2’22

7. BROWN H.C. / Climbing Up the Golden Stairs / Heiser / Columbia, 1917: 2’51

8. CAMMEYER Alfred / Chinese Patrol / Jumbo, 1912: 2’58

9. EARLE Bert / The Bacchanal Rag / Louis Hirch / Pathé 80, - : 2’34

10. FARLAND Alfred / Carnival of Venice / Julius Benedict / Edison, 1917: 4’01

11. HUNTER Parke / Dixie Girl / J.B. Lampe / Victor-Monarch, 1903: 2’35

12. JONES E. / Pompadour / Joe Morley / Columbia, ca.1925 (Neovox): 2’47

13. JONES E. / Nigger Town / Joe Morley / Columbia, ca.1925 (Neovox): 2’38

14. KIRBY Alfred / Heather Bloom / Alfred Kirby / - (Neovox): 2’35

15. MAGHEE Alexander / Jolly Darkies / - , ca. 1950 (Americana): 4’19

16. MORLEY Joe / Japanese Patrol / Joe Morley / Tarrant Bailey Snr. Coll, 1918 (Neophone): 2’23

17. OAKLEY Olly - Bolero / Alfred Cammeyer / G & T, 1907: 3’07

18. OAKLEY Olly / A Banjo Oddity / Joe Morley / - (Neovox): 3’07

19. OAKLEY Olly / The Palladium March / Joe Morley / Pathé, 1923: 2’30

20. PEPPER Will / Dinky’s Patrol / Alf. W. Newton / Columbia, 1904: 3’01

21. PIDOUX John / A Plantation Episode / Emile Grimshaw / Pathé, 1919: 2’52

22. SHAWNEE Ted / Black and White Rag – (Americana): 2’22

23. SPAULDING Shirley / A Footlight Favorite / Emile Grimshaw / - ,1922: 3’29

24. TURNER Sidney / Adante et Waltz / Alfred Cammeyer / Pathé 80, 1913: 2’19

25. TURNER Sidney /ESSEX Clifford / A Bunch of Rags / Vess Ossman / Tarrant Bailey Snr. Coll, 1914 (Neovox): 2’22”

CREDITS:

Transfert des originaux sur cassettes audios:

Wayne Adams, années 1990.

Digitalisation et restauration de ces cassettes

(programme Adobe ‘Audition’): Jean Leroy, 2003.

Restauration (Cedar technology) et masterisation :

Marc Doutrepont (Studio Equus, Bruxelles), 2021.

Relecture du texte en français : Claudine Tricot.

Relecture et Traduction : David Cotton.

Copyrights : G. De Smaele, Frémeaux & Associés, 2022.

Remerciements : Reinhard Gress (Munich).

Margie Smith-Robbins et Lucas Ross

(American Banjo Museum, Oklahoma City).

Elias and Madeleine Kaufman (Buffalo, NY).

Colby Maddox (Old Town School of Folk Music, Chicago).

Alain Pierre (Studio Silence Music, Corbais, BE).