- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

L’astre d’Orient 1926-1937

Ref.: FA5845

EAN : 3561302584522

Artistic Direction : Jean-Baptiste Mersiol & Péroline Barbet-Adda

Label : FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 41 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

L’astre d’Orient 1926-1937

Never has any artist so strikingly represented the soul of a whole people as the singer Umm Kulthum, also known as Oum Kalsoum. This immense Egyptian singer was given the honorific title “Star of the Orient”, and she is today considered one of the greatest singers of all time. Worshipped from Rabat to Bagdad as the muse of the tarab genre, the career of this diva made a vast contribution to the modernization of Arab popular music. The first of this diva’s recordings, dating from 1926 to 1937, have been compiled here by Jean-Baptiste Mersiol, and in the accompanying booklet, radio producer Péroline Barbet-Adda discusses Kalsoum’s unrivalled talents: the singer’s miraculous voice would become the eternal echo of the Arab world’s expression in music, and lead Oum Kalsoum to the avant-garde of feminism in the Orient.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CD1 - 1926 - 1928 : AL SABBE TAFDAHAHO • AFDIHI IN HAFIDZA EL HAWA • YA ASSIA EL HAY • MALI FOUTINTOU • TICHOUF OUMORI • ARAKA ASSI ADDAMI • ANA HALI FI HAWAHA AGAB • YA ROHI • ALBAK GHADAR BI • AMANAM AYOHAL AMAR EL MOTEL • EL CHAKKE YEHYI EL GHARAM.

CD2 - 1929 - 1932 : TEBE ‘INI LEHE • YA BACHIR EL ON • ZOKRA SAAD ZAGHLOUL • YA BAGHRIT EL EID • IFRAH YA QALBI • WEHAKKAK ENTAL MONA WALTALAB • YA FAYETNI OUANA ROUHI MA’AK • EL BOOD ALLEMNI EL SAHAR • GANNIT NAIMI • EL BOODE TALE • OUKAZIBOU NAFSI • LEH TILAWEINI.

CD3 - 1933 - 1937 : AKOUN SAEED • KOULOU MAYEZDAD • OLLEL BAKHILAT • KHAYALEK FIL MANAM • LAIH YA ZAMAN • ALA BALAD EL MAHBOUB • AYOHA AL RA’EHAL MOGED • YAILY WEDADY SAFALK • CHARRAF HABIBAL ALB • MIN ELLI A’AL • KHALLIL DEMOUE LEENI • QADET HAYATI HAYRA ALEYK.

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : JEAN-BAPTISTE MERSIOL ET PÉROLINE BARBET-ADDA

COÉDITION : MUSÉE DU QUAI BRANLY - JACQUES CHIRAC

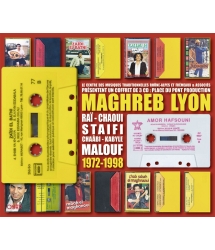

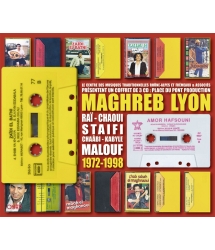

MAGHREB LYON - PLACE DU PONT PRODUCTION 1972-1998

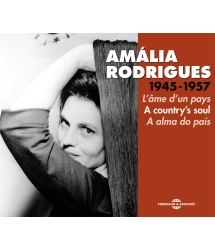

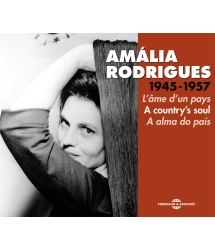

A COUNTRY’S SOUL / A ALMA DO PAÍS

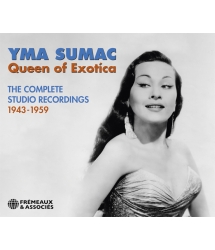

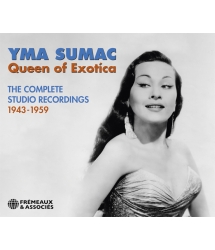

THE COMPLETE STUDIO RECORDINGS 1943-1959

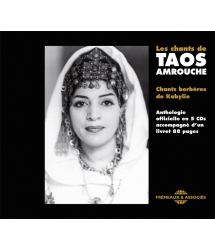

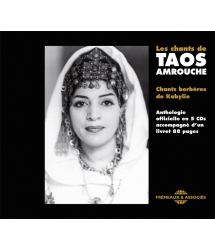

TAOS AMROUCHE

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Al Sabbe TafdahahoOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:05:521926

-

2Afdihi In Hafidza El HawaOum KalsoumAlamasri Ibn Annabih00:07:031926

-

3Ya Assia El HayOum KalsoumIsmail Sabri Pacha00:06:191926

-

4Mali FoutintouOum KalsoumAli Eljarem00:07:461926

-

5Tichouf OumoriOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:06:211926

-

6Araka Assi AddamiOum KalsoumAbou Firas Alhamadami00:06:091927

-

7Ana Hali Fi Hawaha AgabOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:07:151928

-

8Ya RohiOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:06:351928

-

9Albak Ghadar BiOum KalsoumAlamasri Ibn Annabih00:06:211928

-

10Amanam Ayohal Amar El MotelOum KalsoumIbn El Nabih El Mastry00:06:511929

-

11El Chakke Yehyi El GharamOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:07:021929

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Tebe ‘Ini LeheOum KalsoumHussein Hilmy00:05:571929

-

2Ya Bachir El OnOum KalsoumMohamed El Qassabji00:04:491929

-

3Zokra Saad ZaghloulOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:04:391930

-

4Ya Baghrit El EidOum KalsoumAbbas Inb El Ahnaf00:05:181930

-

5Ifrah Ya QalbiOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:05:401931

-

6Wehakkak Ental Mona WaltalabOum KalsoumElham Abdullah El Shabrawi00:06:541931

-

7Ya Fayetni Ouana Rouhi Ma AkOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:05:521931

-

8El Bood Allemni El SaharOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:08:021931

-

9Gannit NaimiOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:05:431931

-

10El Boode TaleOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:05:431932

-

11Oukazibou NafsiOum KalsoumBirk Ibn Nattah00:05:571933

-

12Leh TilaweiniOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:06:071933

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Akoun SaeedOum KalsoumHussein Sob' Hi00:06:231933

-

2Koulou MayezdadOum KalsoumDaoud Hosni00:06:241934

-

3Ollel BakhilatOum KalsoumEl Sheikh Abu Al00:05:231935

-

4Khayalek Fil ManamOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:05:071935

-

5Laih Ya ZamanOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:08:131935

-

6Ala Balad El MahboubOum KalsoumAbdou Sarrouji00:03:191935

-

7Ayoha Al Ra Ehal MogedOum KalsoumAhmed Zakaria00:05:431935

-

8Yaily Wedady SafalkOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:06:321936

-

9Charraf Habibal AlbOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:08:221926

-

10Min Elli A'alOum KalsoumAhmed Zakaria00:06:411926

-

11Khallil Demoue LeeniOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:06:461937

-

12Qadet Hayati Hayra AleykOum KalsoumAhmed Rami00:08:041937

OUM Kalsoum

l’astre d’orient

1926-1937

Jamais aucun artiste n’aura autant incarné l’âme d’un peuple. La grande cantatrice égyptienne Oum Kalsoum surnommée l’Astre d’Orient, figure parmi les plus grandes chanteuses de tous les temps. Adulée de Rabat à Bagdad, égérie du tarab, elle fit beaucoup pour la modernisation de la musique populaire arabe. Jean-Baptiste Mersiol a rassemblé ici les premiers enregistrements de la diva, de 1926 à 1937. La productrice radiophonique Péroline Barbet-Adda nous rappelle dans le livret combien son talent inégalable, voire sacré et sa voix miraculeuse resteront à jamais l’écho intemporel de l’expression musicale du monde arabe et à l’avant-garde du féminisme oriental. Patrick Frémeaux

Never has any artist so strikingly represented the soul of a whole people as the singer Umm Kulthum, also known as Oum Kalsoum. This immense Egyptian singer was given the honorific title “Star of the Orient”, and she is today considered one of the greatest singers of all time. Worshipped from Rabat to Bagdad as the muse of the tarab genre, the career of this diva made a vast contribution to the modernization of Arab popular music. The first of this diva’s recordings, dating from 1926 to 1937, have been compiled here by Jean-Baptiste Mersiol, and in the accompanying booklet, radio producer Péroline Barbet-Adda discusses Kalsoum’s unrivalled talents: the singer’s miraculous voice would become the eternal echo of the Arab world’s expression in music, and lead Oum Kalsoum to the avant-garde of feminism in the Orient. Patrick Frémeaux

CD1 1926 – 1928

1. Al Sabbe Tafdahaho 5’52

2. Afdihi In Hafidza El Hawa 7’03

3. Ya Assia El Hay 6’19

4. Mali Foutintou 7’46

5. Tichouf Oumori 6’21

6. Araka Assi Addami 6’09

7. Ana Hali Fi Hawaha Agab 7’13

8. Ya Rohi 6’35

9. Albak Ghadar Bi 6’21

10. Amanam Ayohal Amar El Motel 6’51

11. El Chakke Yehyi El Gharam 7’00

CD2 1929 – 1932

1. Tebe ‘Ini Lehe 5’57

2. Ya Bachir El On 4’49

3. Zokra Saad Zaghloul 4’39

4. Ya Baghrit El Eid 5’18

5. Ifrah Ya Qalbi 5’40

6. Wehakkak Ental Mona Waltalab 6’54

7. Ya Fayetni Ouana Rouhi Ma’ak 6’54

8. El Bood Allemni El Sahar 8’02

9. Gannit Naimi 5’43

10. El Boode Tale 5’43

11. Oukazibou Nafsi 5’57

12. Leh Tilaweini 6’07

CD3 1933 – 1937

1. Akoun Saeed 6’23

2. Koulou Mayezdad 6’24

3. Ollel Bakhilat 5’23

4. Khayalek Fil Manam 5’07

5. Laih Ya Zaman 8’13

6. Ala Balad El Mahboub 3’19

7. Ayoha Al Ra’ehal Moged 5’43

8. Yaily Wedady Safalk 6’32

9. Charraf Habibal Alb 8’22

10. Min Elli A’al 6’41

11. Khallil Demoue Leeni 6’46

12. Qadet Hayati Hayra Aleyk 8’04

OUM KALSOUM

L’ASTRE D’ORIENT 1926-1937

Par Jean Baptiste Mersiol

et Péroline Barbet-Adda

Oum Kalsoum

et l’enregistrement sonore

par Jean-Baptiste Mersiol

Oum Kalsoum est aujourd’hui l’artiste interprète orientale qui a le plus marqué la musique égyptienne mais aussi le monde de la musique arabe dans son ensemble. Véritable « icône » dans la culture mondiale, nous avons ici choisi de restituer une partie de ses premiers enregistrements qui ont écrit l’histoire. Il existe plusieurs façons d’orthographier son nom : À la base il faudrait l’écrire Umm Kulthūm de son vrai nom Umm Kulthūm Ibrāhīm as-Sayyid al-Biltāǧī. En dialecte Égyptien, on l’écrit ‘Om-eKalsūm, c’est d’ailleurs ainsi qu’on l’entend phonétiquement sur ses premiers disques. Oum Kalsoum est la traduction anglaise de l’arabe mais on le transcrit plus couramment comme cela : Oum Kalsoum. C’est donc cette dernière orthographe qui semble la plus simple que nous choisissons d’employer dans cette anthologie.

Née en 1902, Oum Kalsoum reçoit ses premières leçons de musique par son père et chante le Coran dans le village comme lui-même le fit avant elle. Ainsi elle apprend à bonne école, car cette manière de chanter a dominé en Égypte mais aussi dans le monde arabe. En réalité c’est lorsqu’elle entend son père enseigner le chant à son frère qu’elle souhaite également apprendre cet art. Son père ne tarde donc pas à découvrir l’impressionnante étendue de sa voix si bien qu’à l’âge de dix ans il la fait entrer dans la troupe de cheikhs qu’il dirige pour chanter l’anniversaire du prophète (durant les Mawlid), mais il doit la déguiser en garçon. À seize ans, elle est repérée par le célèbre chanteur Cheikh Abu al-Ila Muhammad qui la sensibilise davantage sur le sens des textes qu’elle chante. Dès 1922 elle part pour le Caire sous l’invitation de Zakaria Ahmed, où elle forme son propre takht : c’est ainsi que l’on désigne une petite formation habituellement composée d’un joueur de qanoun, d’un joueur de cithare arabe, d’un joueur de riq, d’un percussionniste et d’un violoniste. C’est à cette époque qu’elle fait la connaissance de Ahmed Rani qui lui écrira plus d’une centaine de chansons et son fidèle joueur de oud qui l’accompagnera jusqu’à sa mort : Mohamed El Qasabji.

L’anthologie que nous vous présentons ici débute en 1926, date où Gramophone Records lui proposa son premier contrat discographique. Elle enregistrera plus tard pour Odeon et His Master Voice. Selon nos recherches, son premier disque enregistré serait Al Sabbe Tafdahaho. C’est donc ici en 1926 que l’histoire commence. Il faut bien se rendre compte qu’à cette époque l’enregistrement sonore, dans les pays arabes comme en Orient, en est encore à ses balbutiements. La jeune Oum Kalsoum doit chanter en direct face à un pavillon avec son orchestre à peine plus éloigné qu’elle. C’est ainsi que l’on peut se rendre compte de sa puissance vocale et ses dons exceptionnels pour le sens musical. Les premiers morceaux dans le Proche-Orient auraient été enregistrés dès 1893 dans le Midwest américain à l’occasion de l’exposition universelle de Chicago. C’est à cette occasion que le cylindre, invention alors révolutionnaire a été présenté au public. Peu de temps après les firmes Columbia et Edison soucieuses de bénéficier d’un catalogue vaste ont été les premières à commercialiser cette musique. En Europe et plus spécifiquement en France, en Angleterre et en Allemagne, on enregistre également ce type de musique (Pathé, Odéon, His master Voice) et la venue dès le début du vingtième siècle du disque plat à double face va favoriser la production des supports sonores pour ce style de musique présentant des œuvres plus ou moins longues. Nous entrerons alors dans l’ère de l’orchestre oriental. Avec les premiers disques plats, les capacités restent limitées car un 78 tours ne peut contenir en moyenne que trois à quatre minutes de musique par face. Nous sommes donc confrontés à un découpage, voire une décomposition du concert et de la musique savante. Ainsi les titres de Oum Kalsoum que vous entendrez ici ont été quasi tous enregistrés en deux temps et répartis sur les deux faces de leurs 78 tours. Nous avons donc restitué le titre dans son entier par l’emploi d’un montage médian.

Il n’a pas été facile de reconstituer les dates exactes des enregistrements présentés ici pour plusieurs raisons. Les nombreuses publications éditées dans différents pays portent parfois à confusion. Il existe beaucoup de pressages Français, Allemands et Anglais destinés à l’export. La domination des marques de disques américaines et européennes ont favorisé ce commerce international. De plus, le monde arabe n’était autrefois pas aussi féru de la datation et l’archivage sans doute parce que l’on se souciait peu du caractère historique à venir mais aussi parce que dans ce type de musique, ce qui compte, c’est l’intention. Les références de matrices aussi sont multiples, que ce soit sur des 78 tours originaux ou des rééditions en 45 et 33 tours : certains disques ne comportent même pas de référence ! Ainsi nous avons pensé qu’il serait périlleux de communiquer ces numéros qui seraient peu fiables pour le moment. Il conviendrait de faire des recherches poussées sur cet aspect des choses, un travail archéologique et titanesque. À l’écoute de ces enregistrements, l’auditeur pourra être surpris par certaines introductions : l’annonce de l’interprète par un tiers. En réalité, il était coutumier dans les premières années de la phonographie d’annoncer le titre et/ou l’interprète avant la chanson elle-même. En France, Aristide Bruant annonçait lui-même ses œuvres mais cela n’était pas toujours le cas selon les maisons de disques. Il en va de même ici. Nous n’avons pas de précisions si le monde Arabe avait coutume de faire appel à un tiers qui plus est, est masculin, ou si cette annonce revenait de droit au compositeur. Quoi qu’il en soit gardons-en ici le charme et la valeur historique de ces documents.

Les trois CD proposés ici s’étendent de 1926 à 1937 soit sur plus d’une décennie. Ces enregistrements datent d’une époque où la médiation musicale en Orient s’est faite par le disque. C’est en 1932 que celle-ci s’est estompée avec l’arrivée du cinéma parlant en Égypte et qui fit rayonner Oum Kalsoum dans de nombreux films. C’est avec l’arrivée du cinéma et surtout des futurs supports 45 et surtout 33 tours que Oum Kalsoum prendra enfin sa vraie dimension discographique à l’image de ses concerts en enregistrant parfois des œuvres durant plus d’une heure. L’orchestre oriental s’agrandira aussi donnant à cette musique une dimension davantage savante et symphonique. Ce que vous tenez en main est le début de l’histoire d’une icône de la musique arabe, admirée de tous, toutes classes sociales confondues.

Jean-Baptiste Mersiol

Remerciements : Alain Er-radi

© Frémeaux & Associés 2023

Oum Kalsoum

une voix pour l’Orient

Par Péroline Barbet-Adda

C’est une tâche difficile que celle de rendre compte de l’extraordinaire parcours de Oum Kalsoum et de la manière avec laquelle elle a fait battre le cœur de l’Egypte pendant près d’un demi-siècle. Car Oum Kalsoum, c’est 70 ans de carrière, étroitement liés à la destinée de l’Egypte et aux soubresauts du monde arabe.

Il y a autour de la chanteuse un mystère et une aura, une ferveur inégalée. Pour approcher ce mystère, il suffira de se plonger dans l’écoute religieuse de sa voix, de son phrasé suave et solennel, de son souffle et de ses silences. Il suffira de suivre les méandres de ses ornementations et de s’ouvrir aux multiples variations de son chant. C’est une voix qui envoûte et qui transporte, qui sait communiquer à son auditoire des sentiments profonds, avec une puissance dramatique et un aplomb souverain. « Haha » s’extasiait la foule en pâmoison, toute entière suspendue à ses improvisations légendaires. L’état de transe dans lequel elle plongeait ses auditeurs avait de quoi surprendre les observateurs étrangers. Aujourd’hui encore, ses complaintes désespérées animent parfois les radios des taxis du Caire et de Rabat, les échoppes des villes ou des campagnes. La chanteuse touche encore profondément car elle a incarné par sa musique, par son allure et par ses engagements, les promesses d’un modernisme oriental ancré dans ses traditions et ouvert aux idées nouvelles.

À l’école du Coran

Oum Kalsoum, c’est d’abord le récit d’une extraordinaire ascension. Celui d’une petite fille aux ascendances paysannes, devenue Diva. Celui d’une jeune rurale qui passe en quelques années du village à la cour du roi. Née dans Delta du Nil en 1898, issue d’un milieu pauvre, elle fréquente les écoles coraniques dès son plus jeune âge. Elle apprend les textes du Livre Saint et, sous la conduite de son père, entreprend de psalmodier le Coran. Très vite remarquée pour interprétation du texte sacré, la petite Oum anime les mariages, les circoncisions et les fêtes religieuses en chantant avec son père, son frère et ses oncles. Elle n’a alors que 12 ans.

À 16 ans, elle est remarquée par le chanteur Cheikh Abou El Ala Mohamed qui l’encourage à venir se produire au Caire. Elle y rencontrera poètes et musiciens qui assurèrent sa formation et dont elle fit ensuite ses plus fidèles alliés. En 1926, elle signe son premier contrat avec Gramophone Records et sa carrière commence. De musiques de films en concerts, de ses légendaires récitals pour la radio nationale à ses tournées dans le monde arabe, elle a traversé le 20e siècle. Elle a connu et tutoyé tous les régimes, celui du roi Fouad jusqu’en 1936, celui du roi Farouk jusqu’en 1952, celui du président Nasser qui a donné une dimension tout à la fois patriotique et transnationale à son art et sa musique ...

De ses ascendances paysannes, elle restera profondément enracinée dans son terroir. Il y a dans son chant un mélange d’éthique et de dévotion, forgé par ses plus jeunes années. Elle gardera l’humilité et la rigueur des gens du delta comme une morale, une culture, une manière de vivre. De nombreux témoignages racontent son manque d’intérêt pour les mondanités et une certaine austérité quant à son approche de la célébrité. On la disait pudique, discrète sur sa vie privée et profondément pieuse. Elle fut femme-symbole de son siècle passant de la ruralité aux salons du pouvoir, sans renier ses origines ni sa culture traditionnelle

Une rénovatrice

Au milieu des années 20, Oum Kalsoum et Mohamed Abdelwahab vont représenter les deux grands réformateurs de la musique égyptienne. L’héritage de l’école de la Nahda1 devient insuffisant pour satisfaire la soif de nouveauté d’une nation en plein développement, ouverte sur son avenir. Les artistes opèrent tous deux un tournant esthétique en proposant des synthèses originales, entre modernité et classicisme. Pour leur public égyptien, ils s’inspirent des éléments de la musique populaire occidentale, tout en ménageant les structures traditionnelles modales arabes classiques. Oum Kalsoum, c’est une sorte de « Maria Callas qui aurait choisi de chanter comme Edith Piaf », expliquera Frédéric Lagrange2 pour insister sur le fait que c’est une artiste issue des musiques savantes qui va s’orienter vers la musique populaire et créer un nouveau genre ; « la variété noble »3. Cette nouvelle variété arabe va supplanter progressivement les genres plus savants. Ce faisant, Oum Kalsoum et Abdelwahab démocratisent leur musique et l’ouvre à de nouveaux publics, moins élitistes que ceux de la nahda classique. La musique savante égyptienne réclamait effort et initiation ; avec Oum Kalsoum, elle se met à la portée de tous sans pour autant s’en trouver dévoyée. C’est probablement ce qui fait qu’aujourd’hui encore, les gens portent un amour extraordinaire à la chanteuse ; du cireur de chaussures à la commerçante, du dentiste à l’homme de lettres, ils récitent ses poèmes et chantent ses chansons car Oum Kalsoum touche et exalte à l’envie l’âme poète du peuple égyptien.

Les nouvelles formes promues par ces deux figures de proue et la nuée de musiciens qui les accompagnent remplacent peu à peu des éléments anciens de la wasla4. Du takh, l’ancienne formation classique formée des traditionnels oud, nay, qanun et riq, se mélangent désormais des sections de violons, violoncelles, contrebasses, saxophone, accordéon, ou autre guitare électrique. Le langage musical se trouve bouleversé par ces nouveaux orchestres.

Oum s’illustre par son intelligence musicale et s’entoure des meilleurs poètes et de compositeurs de sa génération, comme Ahmad Rami, Ahmad Shafiq Kamel et Bayram al-Tunssi, qui travaillèrent ensemble à l’élaboration de nouvelles formes et de nouvelles compositions. Les chansons longues sont un phénomène lié à la personne d’Oum Kalsoum. C’est une forme générique qui reprend toutes les formes de la wasla ancienne. D’une durée d’une heure, parfois plus, elle permet de nombreuses improvisations qui vont devenir la marque de fabrique de la chanteuse. Ainsi lors de ces fameux concerts pour la radio d’état qu’elle donna dès 1937 où elle ne chantait parfois que deux ou trois chansons, tant elles étaient longues et chargées d’imprévus.

Si musicalement Oum et ses collaborateurs sont novateurs, la langue chantée ne l’est pas moins. Avec ses auteurs attitrés, ils inventent de nouvelles manières de dire l’amour et révolutionnent l’expression de la chanson sentimentale dans la littérature arabophone populaire. Ils épurent les longues plaintes classiques, la mélodie comme le langage poétique, pour composer des images ouvertes, plus abstraites, dans lesquelles tout un chacun pouvait s’identifier. Amour charnel, divin ou patriotique, l’ambiguïté est maintenue, cultivée… et fédératrice ; ne reste plus que le chant brûlant de la passion.

De nouvelles voies de diffusion de la musique

Un autre aspect caractéristique de sa modernité, c’est son utilisation des médias pour diffuser son art et la puissance de sa voix.

Le cinéma

Elle s’est rendue populaire au début de sa carrière par ses apparitions chantées et ses rôles au cinéma (1934-1949). Ces pièces courtes, parfois légères et souvent liées à l’action dramatique, furent rarement interprétées en public. Vous trouverez quelques titres dans l’anthologie composée par Jean-Baptiste Mersiol

Le 78 tours

Depuis le début du 19e siècle, les musiques égyptiennes sont documentées par l’enregistrement. Dès 1903, le disque a donné une idée exacte du type de musique jouée au Proche et Moyen Orient et en a figé certains principes d’exécution. Dès 1926, Oum Kalsoum profita largement du support 78 tours, qui diffusèrent sa voix par l’entremise des compagnies Odéon et Gramophone. Les répertoires enregistrés recouvrent des chants savants (qasida, mawwāl, dōr), des chants sentimentaux légers (ṭaqṭūqa) et ses fameux monologues (mūnūlūg). Il faut avoir à l’esprit que ces pièces sont refabriquées à l’aune de la durée limitée du support. Elles sont des créations provoquées par cette toute nouvelle industrie musicale. Ces enregistrements représentent donc des versions abrégées des œuvres chantées, ils ne donnent qu’une idée partielle de ce que pouvait être la performance publique de ces pièces.

La radio

Le succès d’Oum Kalsoum est amplifié par le radio égyptienne, qui joue rapidement un rôle déterminant dans sa carrière. Elle enregistre ses chansons en studio pour la radio nationale : pièces patriotiques, pièces religieuses, versions condensées des longues chansons sentimentales destinées à être interprétées en concert. Mais plus étonnant, dès 1934 ses récitals au théâtre du Caire tous les premiers jeudis du mois, sont retransmis en direct par la radio égyptienne. Elle est sur l’antenne, en direct, pendant plusieurs heures. Ses concerts radiophoniques sont captés sur le territoire égyptien et à l’extérieur, dans les limites que permet le nouveau poste émetteur. Rapidement le monde arabe, du golf arabique à l’océan Atlantique, communie autour de la voix d’Oum Kalsoum. Partout, de Rabat à Bagdad, on collait l’oreille au transistor, dans une expérience fédératrice hors du commun, qui a vite conféré à la Diva une dimension transnationale.

Une diva politique

Avec l’arrivée de Nasser au pouvoir en 1956, un vent nouveau souffle sur l’Egypte, qui devient pour le Moyen-Orient, un modèle pour toutes les aspirations anti-impérialistes et pan arabiques. Nasser sera un fervent admirateur de la chanteuse, qui ne le lui rendait pas moins. Entre Oum et Nasser, qui se rencontrèrent un peu avant la prise de pouvoir de Nasser, il y eut comme un pacte implicite, nourri du respect et de l’admiration mutuelle qu’ils se vouaient l’un à l’autre. Oum Kalsoum exportera l’accent et le style égyptien, et deviendra un emblème pour toutes les nations porteuses de rêves de liberté nationaliste. C’est ainsi que Oum Kalsoum scella sa musique à la destinée de toute une nation, incarnant ses espoirs de modernité et ses aspirations à l’émancipation.

Si ses chansons patriotiques ne sont pas celles que le public a retenues, elle n’en a pas moins chanté son amour de l’Egypte, la redistribution des terres aux paysans, la construction du barrage d’Assouan.

En 1956, le jour de la nationalisation du canal de Suez, c’est Oum Kalsoum que Nasser fait entendre sur la radio officielle égyptienne.

En 1967, après la guerre des six jours et la défaite de l’Egypte contre Israël, elle s’engage dans une singulière tournée dans tous les pays arabes, pour contribuer à l’effort de guerre et pour redorer les fiertés meurtries. Un an pour sillonner le monde arabe et pour porter le message de l’Egypte. Elle voyage et chante : À Khartoum, à Rabat, au Koweit, elle chante. À Amman où le roi Hussein lui réserve un accueil triomphal dans sa capitale. À Tunis, où Oum est reçue comme un chef d’état. À Beyrouth, à Tripoli, où elle exhorte les femmes à se dévoiler. À Paris (novembre 1967) enfin où dans des concerts d’anthologie à l’Olympia, l’icône de l’Orient chante pour ses frères immigrés, livre une ode au monde arabe et met Paris à ses pieds. Plus de quatre millions de dollars sont alors récoltés et reversés à l’état Egyptien pour se remettre de sa débâcle.

Un enterrement hors du commun

À l’âge de 77 ans, le 2 janvier 1975 Oum Kalsoum meurt d’une crise rénale. Il faut visionner les impressionnantes images de son enterrement pour comprendre ce qu’elle représentait alors. Le peuple qui porte son cercueil, son corps qui vogue comme un navire sur une marée humaine, les scènes de débordements et d’hystérie collective. Près de 2, 3, 4 millions de personnes…. des chiffres approximatifs pour une foule énorme et désespérée venue rendre hommage à celle qui a redonné vie à un rêve révolu de concorde et d’unité

Péroline Barbet-Adda

© Frémeaux & Associés 2023

1. Musique de cour de la fin du 19e siècle en Egypte

2. Culture d’islam, France Culture, 17/04/2011 Emission d’Abdelwahab Meddeb, invité Frédéric Lagrange

3. Frédéric Lagrange, Musiques d’Égypte, Paris, Cité de la Musique/Actes Sud, 1996

4. Suite de pièces musicales, instrumentales ou chantées, écrites et improvisées, composées dans un même mode

Umm Kulthum 1926-1937

by Jean Baptiste Mersiol

and Péroline Barbet

Umm Kulthum and her recordings,

by Jean-Baptiste Mersiol

Today Umm Kulthum is hailed not only as the artist who made the most impression on Egyptian music, but also as the greatest singer the Arab world has ever known. She has become a genuine icon in world culture, and here we have chosen to restitute some of her first recordings, which are now historic.

Her name has been written in several ways: originally it was Umm Kulthūm Ibrāhīm as-Sayyid al-Biltāǧī), and in Egyptian dialect she was known as ‘Om-e Kalsūm, the phonetic spelling of the name that appeared on her first records. Over the years the name has usually been written “Oum Kalsoum,” which appears on discs in her discography, and that is how she is referred to in this anthology.

Born in the Nile Delta, in the village of Tamay e-Zahayra (the date has been given as 1898), Oum Kalsoum received her first music lessons from her father Ibrahim, an imam, and she sang the Quran in the village as her father had done before her. It was a good school for Oum Kalsoum, because that particular manner of singing would dominate in Egypt and throughout the Arab world. She first wanted to become a singer when she heard her father teach her brother, and it wasn’t long before Ibrahim discovered Oum’s astounding vocal range: by the age of ten she had joined the troupe of sheikhs led by Ibrahim, and she sang during the Mawlid (the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad), although her father had to disguise her as a boy… At the age of sixteen she was noticed by the famous singer Sheikh Abu al-Ila Muhammad, who drew her attention to the importance of the texts she was singing. In 1922 Zakaria Ahmed invited her to Cairo, where she formed her own takht (the name given to a small group usually consisting of a qanun (a large zither-like stringed instrument), plus an Arab sitar, a violin, percussion and a riq (a Middle-Eastern tambourine). It was at this time that she met Ahmed Rani, who would write a hundred songs for her, and Mohamed El Qasabji, who became her faithful regular oud player; he would accompany Kalsoum until the day she died.

This anthology begins in 1926, the year when the company Gramophone Records signed Oum to her first record-contract. She would make records later for Odeon and His Master’s Voice, and according to our research the first title she recorded (under the name Omme Kolsoum) was Al Sabbe Tafdahaho. The era marked the debuts of sound-recordings in the Arabic-speaking countries of the Middle East (there were no microphones as such), and the young Oum Kalsoum had to sing into a horn mounted on a phonograph, with the orchestra a little further away. Thanks to records, listeners would realise the power behind her voice and her exceptional gift for music. The first discs to appear in the Middle East are said to have been recorded in the American Midwest as early as 1893 (at the Columbian World’s Fair in Chicago). It was on that occasion that the revolutionary invention called a cylinder was introduced to the public. Shortly later, the Columbia and Edison companies, who intended to develop a vast catalogue, were the first to market this music. Arabian music was also recorded in Europe (France, England, Germany) by the Pathé, Odéon and His Master’s Voice companies, and at the beginning of the 20th century, the arrival of two-sided flat discs encouraged the production of sound-carriers that would be capable of reproducing this style of music and works of a greater duration. It marked the beginning of the oriental orchestras’ era. The first flat discs had a limited capacity because a 78rpm record only contained an average of three to four minutes per side. That made editing necessary, and even the reconstruction of a concert and classical music. So the titles sung by Oum Kalsoum here were almost all recorded in two parts and contained across the two sides of their respective 78rpm records. We have therefore restored the title in its entirety by editing its centre.

It wasn’t easy to reconstitute exact dates for the recordings dealt with here for several reasons, among them the confusion between the many songs released in different countries. A large number of French, German and English pressings were made for export, and international commerce would increase with the dominance of American and European labels. In addition, the Arab world in those days was not known for its precision in dating and referencing records, no doubt because people did not pay much heed to the historic nature of these recordings, an interest that would only come later. There are also multiple matrix references for these recordings, whether original releases (on 78rpm discs) or reissues pressed on 45 and 33rpm vinyl records, and some of them didn’t even have a reference number! One can also note that with this type of music, it was the intention behind the records that counted, not their reference.

In consequence, we thought it would be hazardous to use references that for the moment remain unreliable. Any intensive research into this aspect of Kalsoum’s records would be a colossal task, no doubt more a matter for archaeologists! Listening to these, the introductions may come as a surprise, particularly since the artist is introduced by an anonymous voice... In fact, during the first years of recording it was customary for the title and/or singer to be named before the beginning of the song itself. In France, the voice of Aristide Bruant in person could be heard announcing the titles, but that wasn’t the case with all the record companies. And the same applies here. We do not know whether it was common in the Arab world for an unknown (male) voice to do the introduction, or if announcements were reserved for the composer. However, we have preserved the charm and historical value of these sound-documents.

The three CDs proposed here cover the years 1926 to 1937, a little more than a decade. The recordings date from a period when music spread through the Orient by means of records. This situation would change in Egypt in 1932 with the arrival of “the talkies” after the silent screen disappeared, and numerous films assisted Oum Kalsoum in becoming a household name. Films with sound, and then 45rpm discs (but especially 33rpm records) enabled Kalsoum to take on her true dimension as a recording-artist and concert-performer, and she recorded pieces that lasted over one hour. The oriental orchestra grew also, adding a classical and symphonic dimension to the music. The work you hold in your hand here marked the beginning of the story of an icon in Arab music, a figure admired by everyone, whatever their social class.

Jean-Baptiste Mersiol

With thanks to Alain Er-radi

© Frémeaux & Associés 2023

Oum Kalsoum,

the voice of the Middle East

by Péroline Barbet

An account of the extraordinary career of Oum Kalsoum is no simple matter, partly because for nearly half a century she made the heart of Egypt beat so strongly. Her reign was unshakeable, from the early Thirties until the day she died on February 3rd 1975. And this is the story of an almost seventy-year career, closely tied to Egypt’s destiny and the convulsions of the Arab world.

There is mystery surrounding Oum Kalsoum, an aura and a fervour that are unequalled. To come close to this mystery, it is necessary to delve into her voice and listen to it religiously, to listen to her phrasing, which is suave and solemn, to her breathing and to the silences in her voice. One has to follow the meanders of her embellishments, and remain open to the multiple variations of her song. Oum Kalsoum’s voice is one that bewitches and transports you, a voice that communicates profound feelings to the listener, and it has strange powers filled with drama and a balance that remains unrivalled. Her audience could contain crowds who were close to fainting: they sighed «Aaaah» in ecstasy while they remained suspended by her legendary improvisations. The state of trance into which she plunged spectators astonished foreign observers. Even today, her despairing laments still come from radios inside taxis in Cairo or Rabat, and they ring through stalls and shops in cities and towns in Egypt and Morocco. The voice of this singer still leaves a profound impression, because Oum Kalsoum, through her music, her manner and her commitment, continues to incarnate the promises of an oriental modernism still anchored in its traditions, yet open to new ideas.

The Quranic school

First and foremost, Oum Kalsoum is the story of an extraordinary ascent. It is the story of a little girl of peasant ancestry who rose to become a Diva. A young girl born in the countryside who in merely a few years went from her village to the court of a Queen. Born in 1898 in poor surroundings in the Delta of the Nile, she attended Quranic schools from a very early age, learning the teachings of the Holt Book. Led by her father, her voice learned to chant the texts of the Quran. Thanks to her singing of the Holy texts, she was quickly noticed and was soon featured at weddings, circumcisions and religious feasts where she sang together with her father, her brother and her uncles. She was then only twelve.

At the age of sixteen she was noticed by the singer Sheikh Abou El Ala Mohamed, who encouraged her to go to Cairo to perform, and there she would meet poets and musicians who trained her. They would become her most loyal friends and allies. She signed her first recording contract in 1926 with Gramophone Records, and her career began. From film music to concerts, and from her legendary recitals on national radio to her tours throughout the Arab world, Oum Kalsoum traversed much of the 20th century. She met and became familiar with every regime: that of King Fuad 1st until 1936, the reign of Farouk until 1952, and then the regime of President Nasser, who gave Kalsoum’s art and music a dimension that was at once patriotic and transnational...

From her rural ancestors Oum inherited deep country roots. In her song there is a mixture of ethics and worship that was forged almost from the day she was born. She would preserve the humility and rigour of the people of the Delta as if they constituted at the same time a moral code, a culture and a way of life. Numerous accounts testify to her lack of interest for social niceties, and a certain austerity in her attitude towards celebrity. She was described as modest, someone who remained discreet on the subject of her private life, and a profoundly pious woman. She was the female symbol of her own century, one that passed from rural surroundings to the drawing-rooms of power without denying either her origins or her traditional culture.

Innovation

In the mid-Twenties, Oum Kalsoum and Mohamed Abdelwahab would be the two great reformers of Egyptian music. The legacy of the Nahda school1 no longer satisfied the thirst for new things that belonged to a nation in the throes of evolution that had opened up to the future. Together the two artists were the actors of a turning point in style, as they proposed original syntheses that were situated between modernity and classicism. For their Egyptian public, they drew inspiration from elements in the popular music of the West and adapted traditional classical Arab modal structures. Frédéric Lagrange2 would explain that Oum Kalsoum was “a sort of Maria Callas who had chosen to sing like Edith Piaf,” to emphasise the fact that she was an artist from a classical music background who was leaning towards popular music in order to create a new genre, «noble popular music»3. This new Arab popular music would progressively supplant more learned, classical genres. In doing so, Oum Kalsoum and Abdelwahab democratised their music and opened it up to a new audience, a public less elitist than the classical nahda audience. Traditional, “serious” Egyptian music demanded effort and initiation; with Kalsoum, it would place itself within everyone’s reach without finding itself misappropriated. This is probably what makes people even today express an extraordinary love for the singer; shoe-shiners, shopkeepers, dentists and men of letters are still reciting her poems and singing her songs, because Oum Kalsoum touches and exalts the poetic soul of the people of Egypt over and over again.

The new forms proposed by these two figureheads and the many musicians who accompanied them gradually replaced the older elements of the wasla4. The takh, the old classical orchestra made up of the traditional oud, nay, qanun and riq instruments, would now see the addition of string sections (violins, cellos, and double basses), a saxophone, an accordion or an electric guitar. The musical language found itself turned upside down by these new orchestras.

Oum shone by her musical intelligence and she surrounded herself with the best poets and composers of her generation, such as Ahmad Rami, Ahmad Shafiq Kamel and Bayram al-Tunssi, who worked together to develop new forms and compositions. Lengthy songs were a phenomenon linked to the personality of Oum Kalsoum. They were a generic form that took up all the forms of the old wasla. An hour in length, and sometimes more, this form permitted numerous improvisations that were to become the singer’s trademark. An excellent example of this would be the famous state-radio concerts that Oum was giving by 1937 already; and sometimes she sang perhaps only two or three songs per, concert, because they were so lengthy and laden with unforeseen elements.

If Oum Kalsoum and her collaborators were innovators, the language of song was no less so. With their regular songwriters they invented new ways of speaking of love and they brought a revolution in the expression of sentiments through sung texts that became a part of popular Arab-speaking literature. They reduced long classical laments to their purest, in both the melody and the poetic language, and composed images that were open, more abstract, with which everyone could identify. Love, whether carnal, divine or patriotic, saw its ambiguity preserved, cultivated... and it united the people. What remained was the ardent song of passion.

New ways of spreading music

Another characteristic aspect of her modernity was her use of different media to make the public aware of her art and vocal powers.

Films

She became popular early in her career with her singing appearances and roles in films (1934-1949). These short pieces, sometimes light entertainment and often linked to the film’s dramatic action, were rarely performed in public. You can find some of those titles in the anthology prepared by Jean-Baptiste Mersiol.

78rpm records

Egyptian music was documented by recordings right from the beginning of the 19th century. In 1903 already, discs had already given a precise idea of the type of music played in the Near and Middle East regions, and recordings had established certain rules for performance. By 1926 Oum Kalsoum already enjoyed the benefits of 78rpm records that featured her voice thanks to releases by the Odéon and Gramophone companies. The material that she recorded included classical Arab song (qasida, mawwāl, dōr), light, sentimental songs (ṭaqṭūqa) and her famous monologues (mūnūlūg). One has to keep in mind that these pieces were reconstituted according to the limited duration of the sound-carrier. The songs were new creations instigated by this brand-new music-industry, and so the recordings are abridged versions of vocal works that give only a partial idea of what a public performance of these pieces would have been like.

Radio

Oum Kalsoum’s success was amplified by Egyptian radio, which rapidly played a decisive role in her career. She recorded her songs for the national radio station in a studio: patriotic pieces, religious works, and condensed versions of the lengthy, sentimental themes intended for concert performance. Yet the most astonishing aspect of this medium was that as early as 1934 her theatre recitals in Cairo — on the first Thursday of every month — were also live broadcasts on Egyptian radio. She was on the air, live, for several hours. The radio broadcasts of her concerts were heard across the whole of Egypt and as far as possible beyond that, according to the potential of the radio transmitter concerned. Rapidly, the voice of Oum Kalsoum spread through the Arab world from the Arabian Gulf to the Atlantic. Everywhere, from Rabat to Baghdad, people had their ears close to their radios: it was an experience that brought people together in a united bond that quickly gave the Diva a transnational dimension.

A political Diva

When President Nasser rose to power in 1956, a new wind blew over Egypt. In the Middle East, Egypt became a model for anti-imperialist desires throughout Arabia. Nasser would be one of Kalsoum’s fervent admirers, and she returned the favour. Between Oum and Nasser, whom she met shortly before his rise to power, there was a kind of implicit pact nourished by the respect and admiration they had for each other. Politics enabled Oum Kalsoum to export the accents and style of Egypt, and she became an emblem for all nations that dreamed of nationalist freedoms. Oum bound her music to the destiny of an entire nation: she incarnated its hopes of modernity and its desire for emancipation.

While her songs of patriotism were not those that the public would remember, the themes that she did sing spoke of her love for Egypt, the redistribution of land among peasants, and the construction of the Aswan Dam across the Nile. On the day the Suez Canal was nationalised in 1956, it was Oum Kalsoum whom President Nasser chose to sing over the airwaves of Egyptian national radio.

In 1967, after the Six Days War and Egypt’s defeat by Israel, she embarked on an exceptional tour that took her throughout the Arab countries: her tour contributed to the war effort and boosted pride in people who had suffered. She traversed the Arab world for a whole year, carrying Egypt’s message and singing in Khartoum, Rabat and Kuwait. She sang in Amman, where King Hussein reserved a triumphal welcome for her in the Jordanian capital. In Tunis she was greeted like a Head of State. In Beirut and in Tripoli, Oum exhorted women to remove their veils. And in November 1967, she visited Paris and gave spectacular concerts at the Olympia Theatre, where she sang for her immigrant brothers and sisters and delivered an ode to the Arab world that made Paris kneel before her. Her tour raised more than four million dollars which she donated to the State of Egypt to aid its recovery.

An uncommon burial

At the age of 77, on January 2nd, 1975 Oum Kalsoum died of kidney failure. Footage of her funeral provides an impressive demonstration of how much this artist meant to the people of Egypt. Her casket was taken from its bearers and carried by the people, swaying like a vessel on a sea of human beings amidst scenes of collective hysteria. Up to four million people massed in the streets in a desperate attempt to attend and pay tribute to Umm Kulthum, the icon who had restored life to a nation’s dream of peace and unity.

Péroline Barbet-Adda

© Frémeaux & Associés 2023

1. Noble, secular popular music in Egypt at the end of the 19th century

2. “Culture d’islam”, radio France Culture programme on 17/04/2011 by Abdelwahab Meddeb, guest Frédéric Lagrange

3. “Musiques d’Égypte” by Frédéric Lagrange, Paris, publ.

Cité de la Musique/Actes Sud, 1996

4. A suite of pieces of music, instrumental

or sung, written and improvised, and composed in the same mode

oum kalsoum

l’astre d’orient

1926 - 1937

CD 1 : 1926 – 1928

1. Al Sabbe Tafdahaho (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed El Qassabji) - 1926 5’52

2. Afdihi In Hafidza El Hawa (Almasri Ibn Annabih / Aboulala Mohamed) - 1926 7’03

3. Ya Assia El Hay (Ismail Sabri Pacha / Abou Ela Mehamed) - 1926 6’19

4. Mali Foutintou (Ali Eljarem /Ahmed Sabri Najridi) - 1926 7’46

5. Tichouf Oumori (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed Assabgi) - 1926 6’21

6. Araka Assi Addami (Abou Firas Alhamadami / Zbou Alhazmmouli) - 1926 6’09

7. Ana Hali Fi Hawaha Agab (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed El Qassabji) 7’15

8. Ya Rohi (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed Assabgi) - 1927 6’35

9. Albak Ghadar Bi (Almasri Ibn Annabih / Aboulala Mohamed) - 1928 6’21

10. Amanam Ayohal Amar El Motel (Ibn El Nabih El Mastry / El Sheikh Abu Al – Ola Mohamed) - 1928 6’51

11. El Chakke Yehyi El Gharam (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed El Qassabji) - 1928 7’02

CD 2 : 1929 – 1932

1. Tebe ‘Ini Lehe (Hussein Hilmy / Mohamed El Qassabji) - 1929 5’57

2. Ya Bachir El On (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed El Qassabji) - 1929 4’49

3. Zokra Saad Zaghloul (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed Assabgi) - 1929 4’39

4. Ya Baghrit El Eid (Abbas Inb El Ahnaf / Zakaria Ahmed) - 1930 5’18

5. Ifrah Ya Qalbi (Ahmed Rami) - 1930 5’40

6. Wehakhak Ental Mona Waltalab (Elham Abdullah El Shabrawi/ El Sheikh Abu Al - Ola Mohamed) -

prob 1930 6’54

7. Ya Fayetni Ouana Rouhi Ma’ak (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed El Qassabji) - 1931 5’52

8. El Bood Allemni El Sahar (Ahmed Rami / Daoud Hosni) - 1931 8’02

9. Gannit Naimi (Ahmed Rami / Daoud Hosni) - 1931 5’43

10. El Boode Tale (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed Assabgi) - 1931 5’43

11. Oukazibou Nafsi (Birk Ibn Nattah / Aboulala Mohamed) - 1931 5’57

12. Leh Tilaweini (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed El Qassabji) - 1932 6’07

CD 3 : 1933-1937

1. Akoun Saeed (Hussein Sob’Hi / Riad Soundbati) - 1933 6’23

2. Koulou Mayezdad (Daoud Hosni / Daoud Hosni) - prob 1933 6’24

3. Ollel Bakhilat (El Sheikh Abu Al – Ola Mohamed) - prob 1933 5’23

4. Khayalek Fil Manam (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed Assabgi) - prob 1934 5’07

5. Laih Ya Zaman (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed El Qassabji) - 1935 8’13

6. Ala Balad El Mahboub (Abdou Sarrouji / Riad El Soundbati) - 1935 3’19

7. Ayoha Al Ra’ehal Moged (Zakaria Ahmed / Charif Erradi) - 1935 5’43

8. Yaily Wedady Safalk (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed El Qassabji) - 1935 6’32

9. Charraf Habibal Alb (Ahmed Rami /Daoud Hosni) - prob 1935 8’22

10. Min Elli A’al (Zakaria Ahmed / Abdel Rahman) - 1936 6’41

11. Khallil Demoue Leeni (Ahmed Rami / Mohamed El Qassabji) - prob 1937 6’46

12. Qadet Hayati Hayra Aleyk (Ahmed rami / Riad Sombati) - 1937 8’04