- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

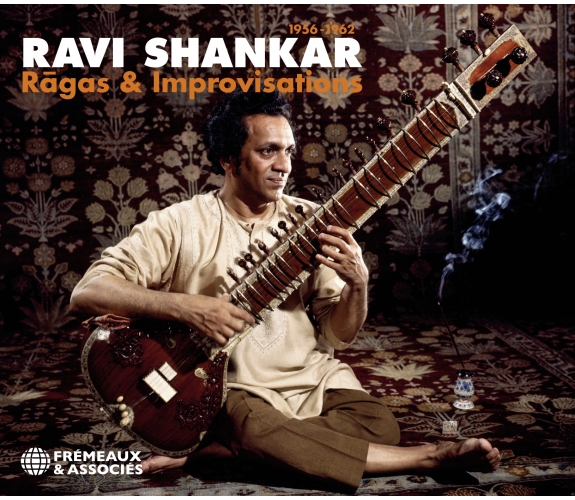

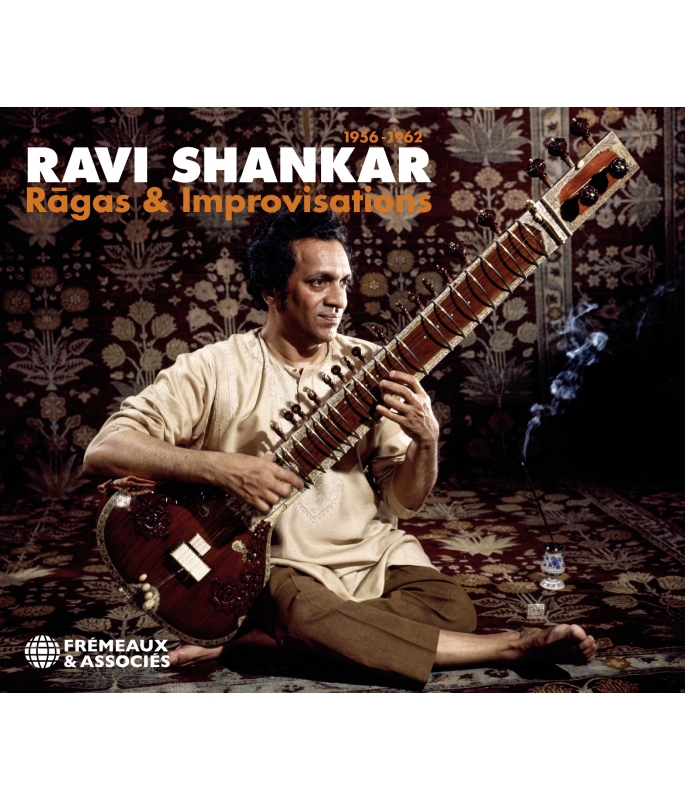

Ragas & improvisations 1956-1962

Ravi Shankar

Ref.: FA5851

EAN : 3561302585123

Artistic Direction : Jean-Baptiste Mersiol & Jacques Viret

Label : FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 20 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

Ragas & improvisations 1956-1962

Ravi Shankar is a major iconic figure of 20th century music, a wonderfully talented sitar player and improviser who remains the best-known musician that India has ever produced. He gave the “raga” of his country a worldwide reputation, and he was a precursor of not only the hippie movement but also the many experiments that took place in rock (George Harrison, Jimmy Page,…) and jazz, and even classical music in the seventies. This anthology prepared by Jean-Baptiste Mersiol and Jacques Viret deals with the first recordings made by the man who would achieve lasting fame as the apostle of world music and the creator of dialogue between our different cultures.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CD 1 - THREE RAGAS : RAGA JOG • RAGA “AHIR-BHAIRAV” • RAGA SIMHENDRA-MADHYAMAM. MUSIC OF INDIA : RAGA HAMSADHWANI (EVENING RAGA) • DHUN KAFI (SPRING SEASON).

CD 2 - MUSIC OF INDIA : RAGA RAMKALI (MORNING RAGA). IMPROVISATIONS : IMPROVISATION ON THE THEME MUSIC FROM PATHER PANCHALI • FIRE NIGHT • KARNATAKI • RAGA RAGESHRI : PART 1 (ALAP) • RAGA RAGESHRI : PART 2 (JOR) • RAGA RAGESHRI : PART 3 (GAT).

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : JEAN-BAPTISTE MERSIOL, JACQUES VIRET

COCHIN - TANJORE - RAMESWARAM

KOKODA

TAOS AMROUCHE

The 60’s Rumba revolution in Congo

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Rāga JogRavi ShankarRavi Shankar00:28:141956

-

2Rāga « Ahir-Bhairav »Ravi ShankarRavi Shankar00:15:281956

-

3Rāga Simhendra-MadhyamamRavi ShankarRavi Shankar00:10:501956

-

4Rāga Hamsadhwani « Evening Rāga »Ravi ShankarRavi Shankar00:09:091962

-

5Dhun Kāfi « Spring Season »Ravi ShankarRavi Shankar00:12:331962

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Rāga Rāmkali « Morning Rāga »Ravi ShankarRavi Shankar00:24:501962

-

2Improvisation On The Theme Music From Pather PanchaliRavi ShankarRavi Shankar00:07:011962

-

3Fire NightRavi ShankarRavi Shankar00:04:311962

-

4KarnatakiRavi ShankarRavi Shankar00:06:381962

-

5Rāga Rageshri : Part 1 « Alap »Ravi ShankarRavi Shankar00:06:491962

-

6Rāga Rageshri : Part 2 « Jor »Ravi ShankarRavi Shankar00:11:011962

-

7Rāga Rageshri : Part 3 « Gat »Ravi ShankarRavi Shankar00:03:181962

Ravi Shankar

Rāgas & Improvisations 1956-1962

by Jean-Baptiste Mersiol and Jacques Viret

Few artists can boast of having exported so much of India’s music around the world. In fact, Ravi Shankar was the only artist capable of making the Indian rāga genre popular with western audiences, and in a manner of speaking, his passion for playing the sitar would provide him with his life’s mission. Historically, few eastern artists had talents that could reach as far as Europe or America, and no other would succeed in influencing so many generations of classical musicians or rock groups.

He was born Ravindra Shankar Chowdhury on 7 April 1920 in Benares (today’s Varanasi), a city held sacred by Hindu pilgrims. He was the family’s fifth child, and his parents called him Robru before he became known as “Ravi”. His father Shyama Shankar had inherited lands east of Bengal, and although he belonged to the priestly Brahmans he had no religious authority (in India the Brahmans are deemed the most important caste). Shyama was a brilliant law student and became a minister under the Maharajah of Jhalawar. After Ravi’s birth, his father went to London as a lawyer, working also in Geneva for the League of Nations, and he finally taught at Columbia University in New York. When Shyama died, “Robru” was only fifteen; he had dreams of becoming an actor, and so joined the troupe of his elder brother Uday, seeing it as an opportunity to perhaps travel to Paris, London and Vienna... And he even moved to the French capital for a while. Then Uday Shankar hired someone he thought was the best musician in India, Allaudin Khan, a sarod and sitar player known for playing a “right-handed” instrument although he was himself left-handed. “Robru” had already been interested in the sitar for some time, and he was full of admiration for the illustrious Allaudin Khan, who quickly accepted to become the young Robru’s guru, on condition that his young pupil devote himself entirely to studying his instrument from then on. Uday dissolved his troupe and decided to return to India. Robru had a revelation, and he shaved his head and took to wearing simple clothes while he spent the next seven years travelling with his master in the tradition of the Guru Kul, an extremely severe initiation that the young man didn’t find it easy to live with, after being accustomed to a life of luxury in palaces and great hotels.

Ravi Shankar would perfect his technique as a sitar player for several long years, learning also the secrets of the surbahar, Rudra veena, rubab and sursingar in the same instrumental family. His many travels would also make him familiar with western music, which he respected and assimilated; it would later allow him to make his own music more accessible. And then in 1956 Robru finally performed in America under the name Ravi Shankar.

1956 was the year that marked the beginning of Ravi’s discography, and this anthology aims to highlight his debuts. For the moment we will limit ourselves to Ravi’s studio recordings from 1956 to 1962. The 1956 release (on the label His Master’s Voice) of “Three Rāgas” is a magnificent testament of the rāga style and a perfect introduction to the genre. That first LP contains three very airy pieces. We are necessarily a long way from the commercial three-minute format of songs played on radio, and so this type of music was rapidly put into the classical music category. Actually, this first record by Ravi was not an exceptional success, but it does show the quality of a first attempt by the artist whom some musicians have called “the most refined musician in the world.”

Ravi Shankar travelled often between India and the United States, and was contacted to arrange the music for the film Anuradha. A 45rpm disc was released in 1960 with four songs taken from the film’s music: Sanware Sanware, Kaise Din Beete, Hayare Woh Din and Jane Kaise Sapanon Me. We won’t reissue them here as they were recorded under the name of singer Lata Mangeshkar (with Ravi Shankar merely an accompanist, and so the titles are not directly Ravi’s works.) Astonishingly, Ravi did not make a second record of his own performances before 1962, but with the release in India of the record Music Of India, Ravi would finally be revealed as he richly deserved, not only in his native India but also in every other country where the record was published. It has to be acknowledged that the success of the film in 1960 contributed to Ravi’s celebrity. Accompanied by tabla player Kanai Dutt, with Nodu Mullick playing the tanpura, Ravi revealed the secrets of the pentatonic scale and the composed bars of Rāga Hamsadhwani. His Dhun Kafi also pays tribute to the season of summer and the god Krishna. The second side contains an entire morning rāga whose subject is the spirit of worship, played between the minor second and sixth intervals and flirting with augmented fourths. This side is actually a shortened version of a stage performance given by Ravi that lasted over two hours.

Following that, Ravi Shankar went into the studios of the label World Pacific. His contract with His Master’s Voice allowed him to record for the labels of other foreign companies. The album Improvisations is in fact a genuine revolution, having a traditional aesthetic while being a model of the modern perspective. To begin with, accompanied by Kanai Dutta and Nodu Mullik, Ravi improvises over the theme music from the film Pather Panchali, which was released to Indian cinemas in 1955. Yet the most surprising piece on the album is “Fire Night,” on which he is joined by Harihar Rao playing a dholak hand-drum, with guitarist Dennis Budimir, bassist Gary Peacock, and drummer Louis Hayes. This piece clearly lies between jazz and rock, and it is certainly the title that paved the way for rock artists: by 1965, Indian music was seducing the likes of George Harrison, who didn’t think twice before incorporating the sitar and other Indian instruments into the music of The Beatles. A strong friendship and understanding developed between the two musicians, and Harrison and Shankar would work together over several decades.

But while Ravi interested musicians from the rock world, he also attracted the attention of some of the great names in classical music, notably violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who was quick to record with Shankar (and a little later, Ravi would join the stable of the prestigious classical label Deutsche Grammophon). Going back to the Improvisations album of 1962, we can note that Bud Shank also contributed to the second side of the record, which is devoted to the Rāga Rageshri in three distinct parts. This side belongs more to the traditional Indian style, and Ravi shows the complete eclecticism that was also one of the reasons for his success. Following this, he recorded India’s Most Distinguished Musician In Concert. We have not re-released this here either due to the fact that it’s not a studio recording, but a public performance.

These early Ravi Shankar recordings throw light on an eclectic discography that is sometimes uneven, although always unrivalled. These first three albums demonstrate the evolution of a musician who was already leaning towards rock and classical music. The next part of his career would show that he was becoming a master, notably through recordings made with André Previn (the Concerto for Sitar made in 1971.) In 1987 Ravi signed with Peter Baumann’s Private Music label and recorded his first pieces with synthesisers. He toured in Russia, collaborated with Philip Glass, and was finally produced by George Harrison, his greatest enthusiast, for a recording of religious songs. Ravi willingly learned western music techniques. He passed away on 11 December 2012 in San Diego. He remains to this day the most famous Indian musician in the world.

Jean-Baptiste Mersiol

Adapted into English by Martin Davies

© Frémeaux & Associés 2023

The rāga:

that which colours the mind.

All the world’s music has a common foundation: the hierarchy of the natural affinities that exist between sounds and consonances: octave, fifth, fourth, third, etc. In the broad sense, this is what we call “harmony”. This general and fundamental given manifests itself in many ways, and it engenders highly diverse musical systems. Hindu music belongs to the modal music category, music that is ordinarily improvised according to strict codes that have been handed down orally from master to student ever since a distant past, including certain evolutions.

Ravi Shankar belongs to the tradition of Hindustan, northern India, which is distinct from the tradition of the South, Karnataka. The two traditions had a common origin until the 13th century when their paths separated. The mode of India is the rāga. As in painting (as Hindu musicians say), where white canvases are covered with shapes and colours, the receptive human mind can be “coloured” by the agreeable, calming sounds of a rāga, sounds that elevate the inner being of the listener to peace and bliss. The rāga is a scale or framework which is exceptional – in the same way as other oriental modes – in that each note is perceived as an interval, a consonance or sound, between itself and the fundamental, fixed note, the keynote. As “the basis of the edifice,” the keynote is the axis, the cornerstone of the musical shape or form. To facilitate the perception of this relationship, it is played throughout a performance in a deep, continuous drone on the tanpura, a plucked string instrument. In addition, each rāga contains a predominant note that is underlined more than the others, the vadi or “resonant.” The second in importance is the samvadi or “co-resonant” on the fourth or fifth interval of the vadi, reinforcing the effect of the latter. The other notes are the anuvadi or “assonant” notes. As for the notes that are foreign to the rāga, the vivadi or “dissonants,” these are excluded except where a dissonance is desired.

As in all traditional cultures, in India, art in general (and music in particular) has a spiritual, religious purpose; the aesthetics of music are never an end in themselves. According to the doctrine, sound is God (Nada Brahma, “God Sound”) and the essence of the universe is in sound, expressed by the mantra Aum or Om. Ancient treatises explain that there are two types of sounds: the anahata nad or “non-struck sounds,” the vibration of the ether, the superior level close to the heavens – a conception similar to the “harmony of spheres” in Pythagoras – and the ahata nad or “struck sounds,” the vibration of air, the lower layer of the atmosphere close to earth. Only the struck sounds are audible, through speech or music. And so the supreme mission of music consists in reflecting this cosmic essence, whose relationships between sounds reproduce numerical configurations. Music, consequently, contributes to the purpose that every Hindu must pursue throughout his terrestrial existence: spiritual fulfilment. To achieve this, one must first know oneself, and first explore one’s own human nature.

Modal notes are scarcely efficient if the musician breathes no life into them: prana, breath, vital energy. The principal means to achieve this are ornaments, gamaka, i.e. the numerous manners of causing notes to resound, or enhancing them and linking them: subtle shadows, delicate nuances of either the sound itself or of two consecutive sounds. Seemingly born of the melody, ornaments are as important to Hindu music as the harmony of chords and counterpoint are to western music. In India, pictorial art is all in finesse, softness and sobriety, and it avoids strong contrasts; music, similarly, is characterised by gracious melodic curves, interlaces of sustained notes, and neatly contrived details.

In this system of music each note conveys a certain expression or emotion. In their ensemble, the notes of a rāga create an entity that is intense and expresses one of the nine rasa-s or “sentiments”, codified for the non-plastic arts whose names are music, dramatic art, poetry and the dance: shringara (the nostalgic love for an absent lover), hasya (laughter, humour), karuna (sadness, nostalgia for God), shanta (peace, serenity, etc.) Throughout, the focus is on a unique state of the soul that is explored, maintained, investigated more deeply, unlike in western works that generally seek the diversity of conscious emotions and compare with the telling of a story by means of sound, not words. This uniformity stems notably from the fact that the “modulation,” that is, the change in mode or keynote in a composition, is never operated, whether in India or in other forms of modal music.

Traditionally, each rāga is assigned to a particular moment of the day or night in order to produce its emotion, but this requirement is difficult to reconcile with modern-day life. The alap, the initial part of an improvisation, states the mode, insists on the principal notes, and brings out its melodic specificities, intervals and characteristic ornaments, in addition to the melodic motif or pakad that causes it to be recognised. Beginning very slowly in a free rhythm, like a meditation, it sketches the “personality” of the rāga with its specific expressiveness. Next comes the section of the alap called jor; the measured rhythm enters here at the same time as the percussion instrument: a tablâ, a little drum doubled with a small kettledrum. The tempo accelerates, the melody figures grow more complex, and we come to the third and final section, the gat or jhala, where the rhythm becomes a more rigorous structure in a codified cycle, the tala. These have highly variable lengths of between three and eight hundred matra (or “metres,” beats). For the rhythm these are the essential element, as are the rāgas for the melody. Each tala contains three types of matra: The sam is the most intense, the tali the least marked, and the khali is silent (“not-struck”). The gat unfolds at a speed corresponding to a growing exaltation, until a kind of final apotheosis.

In his autobiography My Music, My Life, Ravi Shankar wrote that he could be affected by the ugliness and misery in our modern world. Music and dancing, arts to which he had devoted his entire life (dancing in his younger days) were closely attached to the past, and because of that, he sometimes had the feeling that he was closer to the past than to the present. He tried to live in what was good and beautiful, and spontaneously rejected negative waves. For many years, he wrote, with the aid of his master (guru) he patiently made efforts to create a universe of beauty and spiritual strength to which one could turn when the spectacle of the world became depressing. It was this inner beauty that he wished to transmit and cause his listeners to share.

Jacques Viret

Adapted into English by Martin Davies

© Frémeaux & Associés 2023

Discographie

Ravi Shankar

Rāgas & Improvisations 1956-1962

CD 1 :

1. Rāga Jog (Ravi Shankar) 28’14

Three Rāgas – LP His Master Voice ALPC 7 - 1956

2. Rāga « Ahir-Bhairav » (Ravi Shankar) 15’28

Three Rāgas – LP His Master Voice ALPC 7 - 1956

3. Rāga Simhendra-Madhyamam (Ravi Shankar) 10’50

Three Rāgas – LP His Master Voice ALPC 7 - 1956

4. Rāga Hamsadhwani « Evening Rāga » (Ravi Shankar) 9’09

Music Of India – LP His Master Voice ALP 1893 - 1962

5. Dhun Kāfi « Spring Season » (Ravi Shankar) 12’33

Music Of India – LP His Master Voice ALP 1893 - 1962

CD 2 :

1. Rāga Rāmkali « Morning Rāga » (Ravi Shankar) 24’50

Music Of India – LP His Master Voice ALP 1893 - 1962

2. Improvisation On The Theme Music From Pather Panchali (Ravi Shankar) 7’01

Improvisations – LP World Pacific Records WP 1416 - 1962

3. Fire Night (Ravi Shankar) 4’31

Improvisations – LP World Pacific Records WP 1416 - 1962

4. Karnataki (Ravi Shankar) 6’38

Improvisations – LP World Pacific Records WP 1416 - 1962

5. Rāga Rageshri : Part 1 « Alap » (Ravi Shankar) 6’49

Improvisations – LP World Pacific Records WP 1416 - 1962

6. Rāga Rageshri : Part 2 « Jor » (Ravi Shankar) 11’01

Improvisations – LP World Pacific Records WP 1416 - 1962

7. Rāga Rageshri : Part 3 « Gat » (Ravi Shankar) 3’18

Improvisations – LP World Pacific Records WP 1416 - 1962