- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

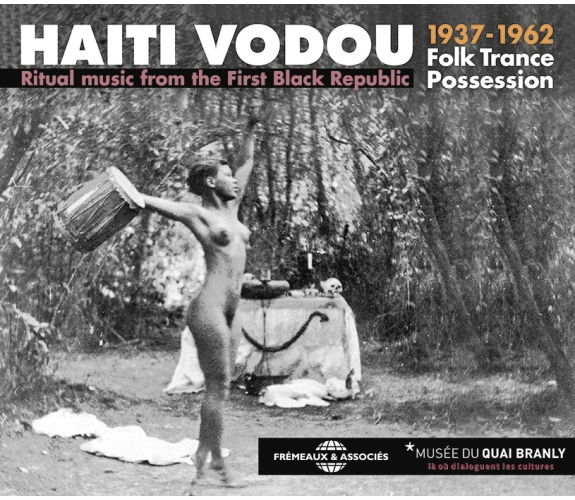

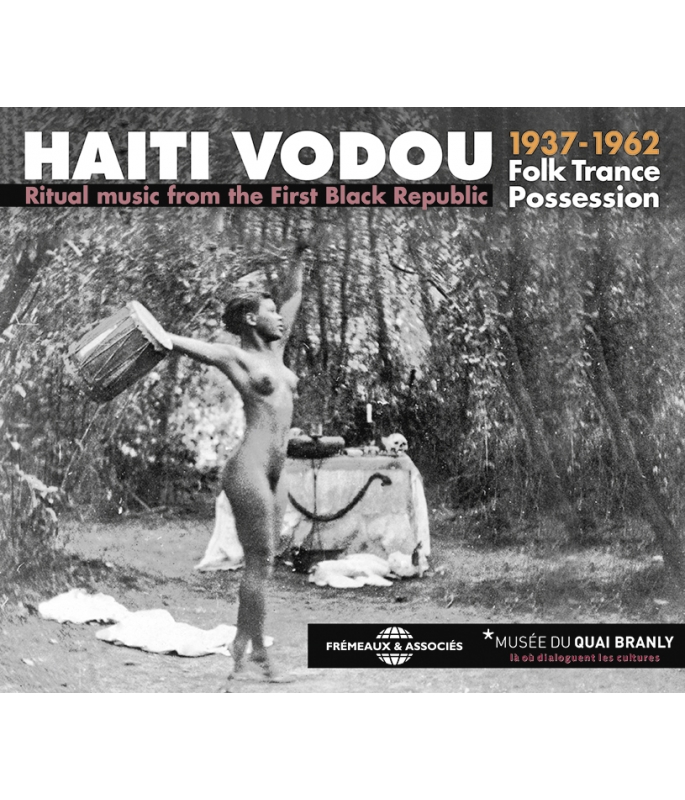

RITUAL MUSIC FROM THE FIRST BLACK REPUBLIC 1937-1962

Ref.: FA5626

Direction Artistique : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 2 heures 33 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

RITUAL MUSIC FROM THE FIRST BLACK REPUBLIC 1937-1962

Un fascinant témoignage des rituels mystiques afro-haïtiens hérités du temps de l’esclavage. Avec ces chants, tambours et transes de possession des initiés, les divinités vaudou étaient invoquées lors de cérémonies authentiques considérées diaboliques par les colons français.

Elles ont inspiré la fiction : zombies, magie…

La révolution haïtienne a été portée par cette religion complexe, qui a unifié les esclaves et galvanisé la lutte pour l’indépendance de la première république noire de l’histoire.

Des milliers d’esclaves haïtiens déportés en Louisiane et à Cuba ont transmis cet héritage vaudou en Amérique du Nord, il est l’une des racines profondes du jazz (jusqu’au rock et au funk) et des musiques afro-cubaines.

Dans ce coffret complémentaire à « Jamaica Folk Trance Possession », Bruno Blum invoque Papa Legba le loa du « carrefour » et de la communication et décrypte ces rares documents, les meilleurs des premiers enregistrements consacrés au vaudou : la clé suprême des musiques afro américaines.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

A fascinating account of the mystic Afro-Haitian rituals inherited from the days of slavery. With these songs, drums and trances of possessed initiates, vodou deities were called upon in authentic ceremonies considered by French colonists as the work of the Devil.

This complex religion inspired fi ctional zombies and magic, united slaves and spurred the fi ght for Haiti’s independence as the fi rst black republic in history.

Thousands of Haitian slaves deported to Louisiana and Cuba spread this voodoo legacy throughout North America, where it became one of the deep roots of jazz (and then rock and funk) and Afro-Cuban musics.

In this companion- set to “Jamaica Folk-Trance-Possession”, Bruno Blum invokes Papa Legba, the spirit of communication, and deciphers some rare sound-documents, the best of the recordings devoted to voodoo: the supreme key to Afro-American music forms.

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : BRUNO BLUM

COÉDITION AVEC LE MUSÉE DU QUAI BRANLY

DROITS : DP / FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

CD 1 - ALUMINUM AND ACETATE DISCS FIELD RECORDINGS 1937-1952 : DANBALA WEDO TOKAN KOULEV - THE SAUL POLINICE, LOUIS & CICÉRON MARSEILLE GROUP • AYIZAN, BELEKOUNDE - FRANCILIA • LA FAMILLE LI FAI CA (IBO DANCE SONG) - LENA HIBBERT • COTE YO, COTE YO (MAIS DANCE SONG) - LIBERA BORDERAU • OGOUN BALINDJO (INVOCATION) - LAFRANCE BELVUE • EZILIE WEDO (INVOCATION) - LAFRANCE BELVUE • SPIRIT CONVERSATION - VAUDOU PRIEST • MOUNDONGUE OH YE YE YE (MOUNDONGUE DANCE SONG) • OU PAS WE’M INNOCENT (SECULAR SONG) - ALEANNE FRANÇOIS • GENERAL BRISE (KITA DANCE SONG) - LAFRANCE BELVUE • VODOUN DANCE (THREE DRUMS) • PETRO DANCE (TWO DRUMS) • QUITTA DANCE (TWO DRUMS) • BABOULE DANCE (THREE DRUMS) • CONGO PAYETTE DANCE (THREE DRUMS) • CONGO LAROSE DANCE (THREE DRUMS) • GANBOS (BAMBOO STAMPING TUBES & OGAN) • VACCINES (BAMBOO TRUMPETS & STICKS) • BUMBA DANCE (TWO DRUMS) • IBO DANCE (THREE DRUMS & OGAN) • CE MOIN AYIDA (ZÉPAULE DANCE) • AYIDA DEESSE ARC EN CIEL (MAIS DANCE) • AYIDA PAS NAN BETISE (PÉTRO DANCE) • MAMBO AYIDA (CONGO DANCE) • LEGBA AGUATOR (NAGO DANCE).

CD 2 - MAGNETIC TAPE FIELD RECORDINGS 1953-1960 : CREOLE O VOUDOUN (YANVALOU)• AYIZAN MARCHE (ZEPAULES) • SIGNALEAGWE ORROYO (YANVALOU) • ZULIE BANDA (BANDA) • GHEDE NIMBO (MAHI) • NOGO JACO COLOCOTO (NAGO CRABINO) • MIRO MIBA (CONGO) • PO’ DRAPEAUX (PETRO MAZONNEI) • DRUMS - BANDA RHYTHM - HAITI DANSE ORCHESTRA • RASBODAIL RHYTHM - HAITI DANSE ORCHESTRA • SERVICE D’OGOUN • SERVICE DE PAPA DAMBALLAH • SERVICE DE ZACCA • WAWALLE AGO • QUI TIREZ BATIMENT AGOUE-TAROYO DERAPE • AGOUE-TAROYO A SIGNALE • CHANT D’OFFRANDE DE LA BAGUE • AGASSOU MA ODE (POSSESSION CHANT).

CD 3 - STUDIO & FIELD RECORDINGS 1953-1962 : PETRO - QUITA - JEAN-LÉON DESTINÉ (DRUM RHYTHM) • SOLE OH (YANVALOU INVOCATION) - JEAN-LÉON DESTINÉ • SHANGO (INVOCATION) - JEAN-LÉON DESTINÉ • AYANMAN IBO - JEAN-LÉON DESTINÉ • DIE, DIE, DIE - JEAN-LÉON DESTINÉ (INVOCATION - ZÉPAULES) • MASCARON-PIGNITTE (CARNIVAL RHYTHM) - JEAN-LÉON DESTINÉ • NEGRESS QUARTIER MORIN - ÉMERANTE DE PRADINES • I MAN MAN MAN - ÉMERANTE DE PRADINES • LOA AZALOU (DIÉ DIÉ DIÉ) - ÉMERANTE DE PRADINES • MRE MRELE MANDE - ÉMERANTE DE PRADINES • ERZULIE - ÉMERANTE DE PRADINES • VOODOO DRUMS (POSSESSION) • NIBO RHYTHM • PETRO RHYTHM • NAGO RHYTHM • PAPA LEGBA INVOCATION • DAHOMEY RHYTHM (ZÉPAULE) • MAIS RHYTHM • DIOUBA RHYTHM (COUSIN ZACA) • PRAYER TO SHANGO.

RHYTHM AND BLUES SHUFFLE

ROOTS OF RASTAFARI 1939 - 1961

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Danbala Wedo Tokan KoulevThe Saul Polinice Louis et Cicéron Marseille GroupTraditional00:01:222016

-

2Ayizan BelekoundeFranciliaTraditional00:01:132016

-

3La Famille Li Fai Ca (Ibo Dance Song)Hibbert LenaTraditional00:01:492016

-

4Cote Yo Cote Yo (Mais Dance Song)Borderau LiberaTraditional00:01:062016

-

5Ogoun Balindjo (Invocation)Lafrance BelvueTraditional00:01:292016

-

6Ezilie Wedo (Invocation)Lafrance BelvueTraditional00:01:162016

-

7Spirit ConversationVodou PriestTraditional00:01:592016

-

8Moundongue Oh Ye Ye Ye (Moundongue Dance Song)Lafrance BelvueTraditional00:01:502016

-

9Ou Pas We'm Innocent (Secular Song)François AleanneTraditional00:00:592016

-

10General Brise (Kita Dance Song)Lafrance BelvueTraditional00:01:462016

-

11Vodoun Dance (Three Drums)InconnuTraditional00:02:502016

-

12Petro Dance (Two Drums)InconnuTraditional00:01:132016

-

13Quitta Dance (Two Drums)InconnuTraditional00:01:242016

-

14Baboule Dance (Three Drums)InconnuTraditional00:01:132016

-

15Congo Payette Dance (Three Drums)InconnuTraditional00:01:142016

-

16Congo Larose Dance (Three Drums)InconnuTraditional00:01:322016

-

17Ganbos (Bamboo Stamping Tubes Ogan)InconnuTraditional00:02:052016

-

18Vaccines (Bamboo Trumpets Sticks)InconnuTraditional00:00:402016

-

19Bumba Dance (Two Drums)InconnuTraditional00:02:402016

-

20Ibo Dance (Three Drums Ogan)InconnuTraditional00:02:372016

-

21Ce Moin Ayida (Zepaule Dance)InconnuTraditional00:02:572016

-

22Ayida Deesse Arc En Ciel (Mais Dance)InconnuTraditional00:02:062016

-

23Ayida Pas Nan Betise (Petro Dance)InconnuTraditional00:02:262016

-

24Mambo Ayida (Congo Dance)InconnuTraditional00:01:532016

-

25Legba Aguator (Nago Dance)InconnuTraditional00:03:292016

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Créole O Voudoun (Yanvalou)InconnuTraditional00:05:052016

-

2Ayizan Marche (Zepaules)InconnuTraditional00:03:242016

-

3Signaleagwe Orroyo (Yanvalou)InconnuTraditional00:03:382016

-

4Zulie Banda (Banda)InconnuTraditional00:03:102016

-

5Ghede Nimbo (Mahi)InconnuTraditional00:04:402016

-

6Nogo Jaco Colocoto (Nago Crabino)InconnuTraditional00:02:512016

-

7Miro Miba (Congo)InconnuTraditional00:03:012016

-

8Po Drapeaux (Petro Mazonnei)InconnuTraditional00:05:502016

-

9Drums - Banda RhythmHaiti Danse OrchestraTraditional00:01:452016

-

10Rasbodail RhythmHaiti Danse OrchestraTraditional00:02:342016

-

11Service D'ogounInconnuTraditional00:01:542016

-

12Service De Papa DamballahInconnuTraditional00:02:302016

-

13Service De ZaccaInconnuTraditional00:02:182016

-

14Wawalle AgoInconnuTraditional00:01:302016

-

15Qui Tirez Bâtiment Agoue-Taroyo DérapéInconnuTraditional00:02:202016

-

16Agoue-Taroyo À SignaléInconnuTraditional00:01:532016

-

17Chant D'offrande De La BagueInconnuTraditional00:01:502016

-

18Agassou Ma Ode (Possession Chant)InconnuTraditional00:02:132016

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Petro - QuitaDestiné JeanleonTraditional00:01:442016

-

2Sole Oh (Yanvalou Invocation)Destiné JeanleonTraditional00:03:142016

-

3Shango (Invocation)Destiné JeanleonTraditional00:02:382016

-

4Ayanman IboDestiné JeanleonTraditional00:02:572016

-

5Die Die Die (Invocation - Zepaules)Destiné JeanleonTraditional00:03:132016

-

6Mascaron-Pignitte (Carnival Rhythm)Destiné JeanleonTraditional00:02:352016

-

7Negress Quartier MorinEmerante de PradinesTraditional00:02:082016

-

8I Man Man ManEmerante de PradinesTraditional00:01:402016

-

9Loa Azalou (Die Die Die)Emerante de PradinesTraditional00:04:142016

-

10Mre Mrele MandeEmerante de PradinesTraditional00:02:012016

-

11ErzulieEmerante de PradinesTraditional00:05:282016

-

12Voodoo Drums (Possession)InconnuTraditional00:05:252016

-

13Nibo RhythmInconnuTraditional00:01:212016

-

14Petro RhythmInconnuTraditional00:00:502016

-

15Nago RhythmInconnuTraditional00:02:412016

-

16Papa Legba InvocationInconnuTraditional00:01:072016

-

17Dahomey RhythmInconnuTraditional00:00:532016

-

18Mais RhythmInconnuTraditional00:03:542016

-

19Diouba RhythmInconnuTraditional00:06:062016

-

20Prayer to ShangoInconnuTraditional00:01:572016

Haiti Vodou FA5626

Haiti Vodou

Ritual music from the First Black Republic

1937-1962

Folk Trance Possession

Comme Jamaica Folk Trance Possession 1939-1961 dans cette collection, ce coffret cons-titue un précieux témoignage hérité directement du temps de l’esclavage. Bien que les rites et les rythmes aient évolué en un siècle et demi il donne une bande son, une réalité tangible à ces obscurs siècles passés et permet presque d’y voyager corps et âme, de s’y plonger instantanément. De rares documents cubains et jamaïcains exceptés, il n’existe pas d’autres enregistrements aussi anciens d’authentiques rituels caribéens. Les musiques liturgiques vodou sont à la véritable source de musiques profanes comme le meringue haïtien, né à la fin du XVIIe siècle (un mélange de contredanse française, de danza et musique de troubadours cubains et de rythmes africains), et du compas apparu dans les dancings de Port-au-Prince au milieu des années 19501. À leur tour, ces styles haïtiens ont été à la racine du fabuleux merengue dominicain développé à l’autre bout de l’île2 et de ses descendants, dont la bomba portoricaine3 (dont le nom provient vraisemblablement du style Bumba Dance entendu ici (disque 1, titre 19) et la salsa new-yorkaise. Arrivées en force dans l’influente région du delta du Mississippi au XIXe siècle, les musiques rituelles vodou haïtiennes, de santería cubaine, de musique sacrée des orishas lucumí (yoruba) et de la société secrète Abakuà des Carabalí (Calabar) à Cuba ont également nourri nombre de negro spirituals. Elles sont aux racines de rien moins que le ragtime, le blues et le jazz de la Nouvelle Orléans, et par conséquent du funk4 et du rock5. Le rythme petro mazonnei (Po’ Drapeaux) est par exemple ternaire (swing), une particularité afro-américaine fondamentale à la racine du jazz et du boogie6. Cependant, avec ses rythmes, chansons liturgiques, cantiques et prières, comme pour d’autres religions la musique n’est qu’un aspect de la culture vaudou (écrit « vodu » en dahoméen, « vodú » à Cuba, « vaudou » en français, « vodou » en Haïti et « voodoo » en anglais). Elle est un des moyens essentiels utilisés pour entrer en contact avec son panthéon de divinités, les loa, lors de transes où l’esprit « chevauche » l’initié. Ces transes ont par exemple eu lieu lors de l’enregistrement de Voodoo Drums et le chant de possession Agassou ma odé. En retour, les esprits des ancêtres inspiraient différentes informations, suggérant des choix et des changements dans la vie des participants.

La musique ne ment pas. Si quelque chose doit changer dans ce monde, ça ne pourra se produire qu’à travers la musique.

— Jimi Hendrix

Le Vodou haïtien

Le vrai mystère du monde est le visible, et non l’invisible.

— Oscar Wilde

La musique et la danse jouent un rôle primordial dans le vodou : elles mettent en scène les rites provoquant les transes. C’est par le truchement de la danse que le vodou plonge le mieux dans le mysticisme ; les mouvements physiques du danseur sont des évocations magiques du monde invisible et attirent le divin. Les divinités et les esprits sont invisibles — tout comme la musique, qui partage avec eux ce privilège.

Le vodou (ou vodoun) d’Haïti est un syncrétisme, c’est à dire une structure religieuse qui assemble des éléments issus de plusieurs religions africaines.

Haïti a connu l’esclavage intensif pendant un siècle, soit beaucoup moins longtemps que ses voisins puisque les planteurs français ne s’y sont véritablement installés qu’en 1697, au terme d’un accord avec l’Espagne qui leur disputa longtemps ce territoire. Cent ans plus tard, et vingt-huit ans après les États-Unis, après une longue et douloureuse révolution menée par des esclaves, Haïti a été le deuxième pays d’Amérique à obtenir son indépendance dès 1804, abolissant l’esclavage avant le reste du monde. Un mélange d’Africains en servitude, marqués par la colonisation française, y avait déjà composé une culture créole particulière, mélangeant différentes cultures africaines où les religions animistes ont toujours tenu une place centrale. Le vodou haïtien est vite devenu un véritable mode de vie, une identité, une spiritualité à la fonction prophétique et libératrice — et un témoignage de résistance. Il a bien entendu été dénoncé par les esclavagistes français, qui le considéraient diabolique et réprimaient ses pratiquants, accusés de sorcellerie. L’interdit qui frappait ce culte des anciens unissait les opprimés. Et comme dans la santería cubaine ou le candomblé brésilien, les esclaves ont déguisé leurs rites avec des éléments liturgiques catholiques, adoptant selon des critères très inattendus, pour ne pas dire farfelus (et non par simple analogie) les saints qui correspondaient à leurs propres divinités, les loa. Ces dieux appartiennent à des familles souvent déterminées par leurs origines africaines polythéistes. En plus du nom d’un saint, chaque loa porte plusieurs patronymes, ce qui contribue à l’inextricable mystère que forment les rites, le panthéon et la mythologie vodou.

Vaudou en Afrique

Différents peuples ont été prélevés par les négriers espagnols et français du XVIIe siècle. Déportés dans l’île appelée Hispaniola par Christophe Colomb (et Saint-Domingue par les Français), les premiers captifs provenaient presque tous de Saint-Louis au Sénégal. Ils étaient des musulmans ouolofs, des mandingues, peuls, toucouleurs ou bambaras. Peu nombreux, ils ont laissé des traces à Haïti où en 1950 on s’adressait encore à certaines divinités avec des termes comme « salam » (les loas sinégal). Puis sont venus les captifs achetés sur l’ancienne côte des Esclaves, où le roi du Dahomey (actuel Bénin) vendait des prisonniers aux Européens. C’est de cette région que vient le terme « vodu » utilisé par les premiers autochtones du plateau d’Abomey, les Ghédé7. Le mot désigne ce qui est mystérieux et relève donc du divin.

On peut estimer que les éléments africains contenus dans les musiques haïtiennes plongèrent d’abord leurs racines chez les peuples de cette région (Ghana, Togo, Bénin et Nigeria actuels) et en particulier les grandes ethnies akan (langue twi), yoruba et ibo. Ce sont ces Dahoméens qui ont donné au vodu son cadre général, sa structure. On retrouve des références directes aux Ibo nigerians dans certains titres (Ibo Dance, Ayanman Ibo, Ibo Dance Song), ainsi qu’aux cultes yorubas : Ogoun Balindjo est une évocation d’Ogoun, l’orisha (divinité) et esprit (loa) de la guerre, du fer, de la chasse, de la politique, de la créativité, de la vérité, des accidents, et à la fois le patron des artisans.

Il est l’un des maris d’Erzulie, d’Oshun, Oya et un ami d’Eshu. Puis, au XIXe siècle, les différentes ethnies bantoues venues de l’immensité forestière du Cameroun/Angola/Congo actuels ont apporté leurs traditions spirituelles et ont enrichi et transformé le vodou. Les cultures africaines ayant été presque effacées du continent nord-américain (les liens directs entre des formes de musiques africaines et le jazz ou le blues américains sont ténus8), ce sont les Caribéens qui y ont apporté les cultures créoles afro-américaines — dont le vodou fut la plus influente.

Le vodou est conçu comme une force immatérielle existant partout dans l’espace, mais à qui l’on peut assigner un point matériel où les initiés peuvent invoquer les loas par des formules connues d’eux seuls. Tel arbre, tel rocher ou tel objet deviennent sacrés le temps d’une rencontre entre la divinité et les possédés. Les captifs étaient appelés par plusieurs vocables dont Arada (du nom du royaume local d’Ardra), qui désignait une langue commune à la région (leur héritage est une série de rites dits rada). Le roi du Dahomey était un Fon et les Fons ne pouvaient être vendus comme esclaves, sauf les rebelles et les criminels. Les Ghédés, à qui le roi faisait la guerre, ont été les principales victimes de la traite. À partir de 1777, des captifs appelés Congos ont été faits prisonniers sur les rivages des actuels sud Bénin, Cameroun, Guinée Équatoriale et une partie de l’Angola. Ils sont distincts de ce qu’on appelait les Franc-Congos, venus de la région de l’actuel Congo. Beaucoup avaient été baptisés par les Portugais, notamment près du fleuve Congo, et avaient des notions de catholicité. Comme au Brésil, ces Chrétiens joueront un rôle important dans le syncrétisme entre religions animistes et catholique à Saint-Domingue. Au Brésil les origines ethniques des différentes formes de candomblé définissent des cultes séparés, tandis qu’au contraire le vodou haïtien est plutôt une synthèse, un mélange de rituels africains analogues mais distincts. La religion a toujours joué un rôle d’intégration dans les conflits africains. Le roi du Dahomey accueillait les dieux vaincus, et les vaincus adoptaient les dieux des vainqueurs, qui — c’est logique — étaient plus puissants. Certains de ces innombrables esprits des ancêtres étaient de véritables dieux et les invocations qu’on leur adressait se faisaient en musique. Ainsi, la pratique fervente de la religion se confondait avec la pratique fervente de la musique.

La musique est ma religion.

— Jimi Hendrix

Invocations des esprits

If I don’t meet you no more in this world/Then I’ll meet you on the next one/And don’t be late/Cause I’m a voodoo child/Lord knows I’m a voodoo child

Si je ne te revois pas en ce monde/Je te reverrai dans le prochain/Et ne sois pas en retard/Car je suis un enfant vaudou/Dieu sait que je suis un enfant vaudou.

— Jimi Hendrix, Voodoo Chile (Slight Return), 1968.

Ayizan, une divinité dominante dans le vodou haïtien, est une tradition des Ajas, des ancêtres des rois du Dahomey qui après une scission d’avec les Aladahonous (à l’époque de la Renaissance) conquérirent la région. Les Ajas créèrent Ayizan, qui devint la grande prêtresse vodou (la mambo) archétype du genre. Divinité du commerce et des initiations, elle détient le savoir des mystères. Avec son époux Loko Atisou elle joue un rôle dans les rites initiatiques kanzo, qui permettent de confirmer les prêtres vodou (appelés à Haïti les houngans) selon les règles liturgiques. Ayizan est invoquée ici dans Ayizan Marche, qui est liée à la danse zépaules (où l’on agite les épaules, comme dans la danse érotique américaine shimmy des années 1960 où les épaules remuent en rythme d’avant en arrière, chacune à leur tour). Cé Moin Ayida se danse aussi dans le style zépaules : Damballah Wédo (qui peut être représenté en Saint Patrick dans son costume de saint catholique) dit Damballah est le nom du grand dieu serpent (évoqué aussi dans Soleh Oh de Jean Léon Destiné). Sa femme s’appelle Ayida Wédo, une loa et un nom venus du Dahomey. Elle est la divinité de la fertilité, des arcs-en-ciel, du vent, de l’eau, du feu et des serpents : le « serpent arc-en-ciel » à qui l’on offre des objets blancs (riz, coton, etc.). Ogoun Balindjo évoque lui l’orisha yoruba Ogoun. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, qui proclama l’indépendance de Haïti en 1804, était fortement identifié au puissant Ogoun, seigneur de la guerre. Une musique lui est consacrée dans Service d’Ogoun. Shango est lui un orisha, le dieu yoruba du feu, des éclairs et du tonnerre. Agassou, descendant d’un mi-homme mi-panthère, naquit également en ces siècles lointains. Il est évoqué dans Agassou ma odé, un chant de possession.

Le panthéon du vodou contient des dizaines de loas portant tous des noms différents et prenant parfois l’apparence de saints catholiques, un vernis hérité de la croisade des ecclésiastiques contre ce qu’ils appelaient la « superstition » et une prétendue « magie noire ». Le clergé détruisait néanmoins les icônes vodou dans des autodafés où ils brûlaient des images de la vierge et des saints en raison de l’usage détourné qui en était fait. Car derrière cette façade chrétienne pittoresque, les secrets ont toujours fait partie de cette cosmologie mystérieuse. En outre les interprétations personnelles ont toujours tenu leur place dans cette religion populaire, non dogmatique. Le vodou se pratique dans des sanctuaires appelés hounfor, au centre duquel trône le poteau mitan par lequel descendent certains loas.

Comme dans d’autres cultes caribéens, notam-ment le kumina et le pukkumina jamaïcain9, l’obeah des Bahamas10 ou les Orishas de la Trinité11, les tambours sont la base musicale qui ouvre la porte aux esprits. Ceux-ci désignent alors leurs élus, seuls capables de communiquer avec eux pendant la transe.

Musique vodou haïtienne

Il existe plusieurs types de danses vodou. Elles sont associées aux rythmes joués sur les tambours, eux-mêmes affiliés à des nachons (nations), des groupes religieux qui les utilisent dans leurs rites et emploient chacun des instruments différents. Voici les principales nations et leurs danses, dont on retrouve les noms accolés à certains des titres ici :

• Rada (trois tambours : le plus grand peut faire un mètre de haut et s’appelle manman, le segon de taille moyenne et le petit boula sur lequel est joué la croche, coniques et fins comme ceux du Nigeria, Bénin et Togo). Ils jouent ces rythmes, qui correspondent à des rites : yanvalou, yanvalou dos-bas, yanvalou-zépaule, parigol, fla voudou, nago, mais/mahi ou mayi (ethnie Mahi du Bénin actuel), daomé (Dahomey), etc. Les tambours rada jouent les rites et ry-thmes dan-women, djapit, ibo (ibo krabiyen, ibo iloukanman), twarigol. L’ogan est une cloche de fer accompagnant souvent le rythme des tambours radas. L’ason (calebasse enveloppée dans une nasse de colliers de perles, secouée en rythme, que l’on retrouve au Cameroun et l’agogo du Nigeria) est parfois présent, ainsi qu’un éventuel tambour bas (basse) additionnel.

• Nago : les loas nago représentent la puissance masculine et sont associés au dieu yoruba du fer et du feu Ogoun/Ogun Feray (ferraille). Un aspect militaire habite leurs danses et rythmes, également appelés nago.

• Djouba : les loas djoubas, notamment Azaka, sont ceux de l’agriculture et ressemblent à des paysans. Ils sont plongent leurs racines en Martinique. Rythmes et danses : baboul/baboule (et ses variantes baboul-kase, baboul krabiyen, baboul woule etc.) abitan, djouba/juba et rites matinik (Martinique).

Les musiques rada, nago et djouba présentent plus de similitudes (peaux de vache, bois dur, baguettes pour les tambours, trois tambours à pinces, organisation plus rigoureuse, voire même tempérée, mesures à trois temps) que les petwo, kongo, ibo et ghède, qui en présentent d’autres (peau de chèvre, bois souple, deux tambours frappés avec les mains, musique informelle, mesures à deux temps).

• Petro (deux petits tambours) : Les loas petwo (ou petro) sont agressifs, protecteurs, exigeants et vifs. Ils représentent les esprits des premiers esclaves haïtiens (dont un des chefs de la rebellion Jean Pedro, qui a donné son nom à un loa) et les âmes des indiens indigènes taïnos (Ayiti est le nom taïno originel de l’île). Ils ont tous été invoqués dans la guerre d’indépendance où Dessalines vainquit les soldats de Napoléon Ier en 1803. Les rythmes et danses s’appellent petwo, makiya ou makaya, bumba, kaplaw, kitammoyé et kita (quitta).

• Kongo : les loas kongos dont Kongo Zando et Rwa Wangol sont les ancêtres des Bantous (Cameroun, Angola, Congo actuel). Colorés, gracieux, ils aiment la musique, les chants et les danses, et leurs musiques sont aussi interprétées à des occasions non rituelles (kalinda, kongo pile, kongo kaase, kongo siye, kongo lazil, kongo krabiyen, kongo larose).

• Ibo : leurs exigeants loas dont le bavard Ibo Lélé proviennent de l’ethnie Ibo (sud-est Nigeria actuel). Leur trait marquant est la fierté, presque arrogante. Lors des rituels les âmes des possédés se logent dans des pots sacrés, les kanaris contrôlés par les esprits. Les chants et danses de leur nation s’appellent aussi Ibo.

• Ghède ou Gède : Les esprits de l’érotisme et de la mort, qui contrôlent le cycle de la vie dont Ghède Nibo, Baron Lakwa Ghède Zarien. Comme Baron Samedi, qui est macabre, obscène et vit dans les cimetières, ils jouent des tours et sont représentés par des visages blancs aux corps habillés de noir. Les cérémonies se terminent généralement par des rites nécromanciens banda ghèdes et leurs danses et chants banda sur tambours petro (Banda est aussi une ethnie d’Afrique Centrale aux musiques polyphoniques très élaborées). Ces personnages effrayants participent à la légende des zombies.

Contrairement aux musiques rituelles traditionnelles jamaïcaines (album Jamaica Folk-Trance-Possession 1939-1961), les musiques folkloriques haïtiennes et les rituels vodou ont été largement documentés, enregistrés et mêmes filmés. En outre le vodou n’a cessé de prospérer depuis et les productions d’enregistrements de tambours et rites vodous se sont accumulées depuis les années 1960. Comme le candomblé brésilien ou la santería cubaine, le vodou est largement répandu. Il existe sous différentes formes et réunit des millions d’adeptes de l’Afrique de l’ouest aux Caraïbes et, dans une forme diluée, jusqu’en Louisiane et au-delà. Inversement, les rites afro-jamaïcains se sont principalement cristallisés autour du mouvement syncrétique Rastafari et ses tambours nyabinghi, se tournant paradoxalement vers l’Afrique tout en délaissant une grande partie de l’héritage musical afro-jamaïcain, notamment les tambours des marrons12. Le grand batteur de reggae Sly Dunbar s’applique à recycler les rythmes ancestraux dans le reggae et le dancehall, mais une grande partie de la culture musicale animiste jamaïcaine s’est évaporée au XXe siècle. En revanche, quantité d’informations sont disponibles sur Haïti et ses musiques rituelles. D’autres enregistrements de tambours caribéens existent (Cuba, Trinité, Guadeloupe13 etc.) et peu-vent être comparés et étudiés.

Rituals Folk Trance Possession

Haïti a toujours souffert d’un isolement politique dû à son édifiante histoire révolutionnaire. Dans le processus de déconsidération qui a accompagné sa mise à l’écart, le vodou a été diabolisé. Haïti a longtemps été considéré comme un chaudron de magie noire maléfique, peuplé de zombies et autres monstres, y compris par les élites haïtiennes elles-mêmes — sans parler des dirigeants de leurs adversaires historiques de Saint-Domingue, qui occupaient l’autre partie de l’île et méprisaient ostensiblement et hypocritement toute culture non européenne14. La nouvelle de William Seabrook The Magic Island (1929) est un bon exemple des stéréotypes de malfaisance attribués au vodou. Contrer ces mythes racistes ne fut pas tâche facile pour les scientifiques qui les premiers étudièrent et documentèrent la culture locale.

Disque 1

Alors que l’universitaire James Leyburn publiait en 1941 The Haitian People15 qui décrit la fracture entre élites et peuple haïtien, le grand anthropologue américain Melville Jean Herskovits publia The Myth of the Negro Past16 (1941), un livre pionnier qui présentait le concept de « race » comme une classification socio-culturelle, et non biologique. Son directeur de thèse avait été l’Américain Franz Boas, un pionnier et géant de l’anthropologie moderne, et l’un des premiers à s’opposer aux théories du racisme scientifique dont le ministre français Paul Bert avait été l’un des plus ardents défenseurs17. Herskovits séjourna en Afrique (notamment au Dahomey) et en Haïti, et établit un réseau de recherches sur les cultures africaines et afro-américaines bousculant les idées en place selon lesquelles les afro-américains auraient été acculturés, perdant l’ensemble de leur héritage culturel africain18. Il publia en 1937 l’essentiel Life in a Haitian Valley19 qui décrit le quotidien des adeptes du vodou avec précision. Un de ses élèves à l’université de Columbia fut Alan Lomax, un texan diplômé en philosophie dont le père John était déjà un pionnier de l’enregistrement de terrain de musiques folkloriques. Alan Lomax deviendra célèbre pour ses enregistrements de musique folk aux États-Unis, qui pérenniseront un immense patrimoine. C’est à l’époque où Herskovits rédigeait son livre de référence sur le vodou que Lomax commença sa carrière en s’embarquant pour Haïti à l’âge de vingt et un ans. Il y séjourna quatre mois, bravant le paludisme, la police secrète hostile aux Américains (Haïti venait d’être occupée par les États-Unis) et la barrière de la langue. Arrivé en décembre 1936, il en revint avec plus de cinquante heures d’enregistrements de terrain réalisés avec un graveur de disques en aluminium Thompson et un micro RCA Velocity20. Le matériel du jeune homme était archaïque et la qualité du son n’étant pas satisfaisante, seuls deux de ces documents historiques ouvrent cet album.

Inspiré par les livres de Seabrook, l’écrivain Harold Courlander voyagea en Haïti plusieurs fois et publia le livre Haiti Singing en 1939. Ethnomusicologue et folkloriste spécialiste des pratiques religieuses du pays, fasciné par l’héritage africain aux Amériques, Courlander publia en 1960 le classique The Drum and the Hoe: Life and Lore of the Haitian People. Sa nouvelle The African (1967) raconte la lutte d’un esclave cherchant à préserver sa culture. Elle sera plagiée dans les années 1970 par Alex Haley dans sa série télévisée sur l’esclavage, The Roots.

Fondé par l’ethnologue et écrivain communiste haïtien Jacques Roumain en 1941, un bureau d’ethnologie ouvert à Port-au-Prince a entrepris de démystifier le vodou et de mieux l’étudier. Herskovits comme Lomax travaillèrent avec l’institut américain Smithsonian où Harold Courlander publia en 1952 les albums Folk Music of Haiti, puis Drums of Haiti et Songs and Dances of Haiti dont la qualité de son était meilleure (les prises de son avaient été effectuées sur des disques en « acétate », une laque de nitrocellulose, plus fidèle). Cette anthologie puise dans ces trois albums historiques.

La Famille li fait ça déclare que le loa ibo Lazile danse et demande à sa famille (les pratiquants) d’en faire autant. Coté yo, coté yo (rituel arada-nago) est une danse héritée de l’ethnie béninoise Mahi (Mais). La chanson loue l’esprit Sobo, protecteur de l’hounfor (temple). Comme sur Ganbos (titre 17), on peut entendre ici des ganbos21 (bambou bouché du côté frappé au sol). Ogoun Balindjo est une invocation du loa yoruba Ogoun. La chanteuse se plaint qu’un voisin vienne l’espionner pour ensuite répandre des potins ; Ezilie Wédo invoque la loa Erzulie, épouse de Damballah Wédo. Dans ce rituel arada-nago les sentiments de liberté de la loa sont évoqués : elle n’est « plus en Afrique » et peut faire ce qu’elle veut. Le fragment Spirit Conversation a été enregistré pendant la transe d’un houngan (prêtre), qui converse avec un loa et des esprits de ses ancêtres tandis que des femmes commentent ce qu’il dit. Moundongue yé yé yé est une chanson du cycle de rites hérité du culte mandingue de Guinée équatoriale-Congo. En 1952 « Moundongue » était encore une insulte, les esclaves mandingues étant considérés cannibales et sauvages. La chanson décrit le repas réalisé par le loa Moundongue après le sacrifice d’une chèvre. Ou pas we’m innocent est une demande de jugement par le loa Ferei (Ogoun Ferraille), le chanteur jurant son innocence. Il est aussi question du sacrifice d’une chèvre. Général Brisé est un loa Kita (Congo-Guinée) auquel l’interprète chante que le pays est dans les mains de dieu.

En raison de l’émigration des planteurs français fuyant la révolution haïtienne à partir de 1791, un grand nombre d’esclaves haïtiens a été emmené en Louisiane, havre catholique francophone sur le proche continent nord-américain, alors dominé par les Espagnols et les protestants anglo-américains. L’album Drums Of Haiti contient des enregistrements de tambours rituels dont les rythmes sacrés, joués au XIXe siècle sur Congo Square22 et au Mardi-Gras à la Nouvelle-Orléans, sont à la racine de nombre de musiques afro-américaines du XXe siècle — jazz, meringue, salsa, funk, etc. Ces titres en sont des indices cruciaux23, un témoignage ancien de cette puissante culture musicale afro-créole surgissant dans l’ADN des musiques américaines mutantes. Bien que les musiques évoluent partout, ces tambours rituels exprimant des coutumes ethniques ancestrales ressemblent certainement à ceux entendus lors des fameuses bamboulas du XIXe siècle, embryons du jazz à Congo Square. Selon Harold Courlander, Baboule Dance (trois tambours à main) serait la même danse que la fameuse bamboula observée par des voyageurs dans d’autres îles de la région à l’époque. Elle était liée au rite djouba issu de la Martinique. L’étymologie de « bamboula » (couramment attribuée aux baguettes de bambou frappant les tambours) remonte très probablement à cette danse liturgique qui inspira en 1845 la pièce romantique de Louis-Moreau Gottschalk intitulée « Bamboula, danse des nègres ». Cette composition est une évocation de ces rythmes entendus à la Nouvelle-Orléans. Elle a beaucoup contribué à faire valoir l’originalité de ce compositeur (qui fit ensuite un triomphe en Europe) 24. L’ironie a voulu que la musique américaine de tradition écrite, jusque-là considérée comme un piètre dérivé des œuvres européennes, reçut avec Gottschalk ses premières lettres de noblesse, validées par les institutions européennes et Chopin lui-même. Le rythme de Baboule Dance (et d’autres entendus ici) fait partie des racines profondes d’une partie du jazz américain. Les improvisations vocales inspirées pendant certaines transes sont, en outre, à la source des improvisations instrumentales et vocales scat dans le jazz.

Vodoun Dance était en 1950 une danse liturgique vaudou fondamentale et Ibo Dance celle du culte ibo hérité du vodu « dahoméen » originel. Petro Dance (rite Congo-Guinée) est caractéristique de ce style. Quitta Dance (Congo-Guinée) est une invocation adressée au loa Cymbi.

Congo Payette Dance (trois tambours à main) a engendré une danse profane exécutée dans les carnavals, le « Congo-paille ». Le son « tambour parlant » appelé tama en ouolof/sérère/mandingue/bambara est obtenu en glissant le doigt sur la peau pour la tendre et la détendre. Sur Vaccines, on entend la « trompette bambou », la vaccine. Le rythme complexe Bumba Dance (rite petro) prend son nom à l’ethnie Bumba (nachon Congo-Guinée). Cé moin Ayida est une supplication à la loa Ayida Wédo (panthéon Dahomey) symbole du serpent sur laquelle se danse le zépaule, suivi de Ayida Déesse arc-en-ciel, qui se transforme en serpent. Ayida Pas nan betise fait partie d’un rite petro différent du précédent : Ayida y est une loa petro bien distincte. Mambo Ayida (prêtresse Ayida) mentionne la Guinée (Équatoriale) et Legba Aguator (esprit de la communication, du carrefour) est un membre du panthéon vodou Ochan Nago. Il faudra attendre l’après-guerre pour que la qualité des enregistrements de terrain progresse avec l’essor de la bande magnétique à partir de 1949 environ. C’est l’objet du disque suivant.

Disque 2

La cinéaste juive d’origine ukrainienne Eleanora Derenkowskaia, qui prit le pseudonyme de Maya Deren aux États-Unis en 1943, fut l’une des premières ethnologues à étudier, documenter, filmer et enregistrer des cérémonies vodou, et ce dès 1947. Elle a pu saisir sur le terrain des documents sonores particulièrement remarquables comme Creole o vodoun ou Ayizan marche. Alors débutant, Jac Holzman, le futur découvreur des Doors et d’Iggy Pop, publia l’album de musiques rituelles authentiques Voices of Haiti de Maya Deren, intégralement inclus ici (Holzman récidivera bientôt en enregistrant chez lui le splendide album de Jean Léon Destiné inclus sur le disque 3). Les rites associés à cet album figurent au côté des titres. Également auteur de l’un des premiers livres de référence sur ce sujet25, la brillante cinéaste d’avant-garde commenta ainsi le sens philosophique du vodou, sa nature religieuse26 et les préjugés qui le discréditaient :

« Quand un Haïtien chante une chanson à un loa, il exécute un mantra ; mieux il s’y voue corps et âme, avec discipline, et plus il est récompensé. Quand il participe à une cérémonie prolongée il réaffirme ses propres principes : destin, force, amour, vie, mort ; il récapitule sa relation à ses ancêtres, à son histoire et à ses contemporains. Il exerce et formalise sa propre intégrité, sa propre personnalité, il renforce ses disciplines, confirme sa morale. En somme, il en ressort avec un sens renforcé et rafraîchi de sa relation aux éléments cosmiques, sociaux et personnels. Une personne intégrée de la sorte fonctionnera vraisemblablement de façon plus efficace, ce qui sera visible dans le succès relatif de ses projets. Le miracle est donc, en un sens, intérieur. C’est l’exécutant qui se retrouve modifié par le rituel ; par conséquent, c’est en fonction de son changement interne que le monde sera pour lui différent. Telle est la nature de la bénédiction supposée récompenser tout dévot d’une religion. Si le vodou n’avait pas été autant calomnié et incompris, confondu avec superstition et magie, tout cela serait admis et il ne serait pas nécessaire de détailler ici son caractère authentiquement religieux. »

— Maya Deren, notes de pochette de l’album Voices of Haiti (Elektra, 1953).

En 1953 paraissait également l’album Voodoo - Authentic Music of Haiti alternant des chansons folk d’Émerante de Pradines (disque 3) et des enregistrements de rituels. Trois tambours rada sont utilisés sur Drums. Sur ce rythme banda les partenaires dansaient sans jamais se toucher. Rasbodail Rhythm est interprété par un orchestre de tambours sur un tempo rapide et gai. Bien qu’originaire d’Inde et différant des musiques aux racines africaines, ce style était intégré dans la culture haïtienne et des musiciens pratiquant le vodou participaient à l’interpréter.

Suit Rituel vaudou en Haïti, où après trois services invoquant des loas (Ogoun, Damballah Wédo et sa femme Ayida Wédo, Zaca), cinq titres sont consacrés à la cérémonie d’offrande d’une bague au loa de la mer (Ife), Agoué-Taroyo.

Disque 3

Jean Léon Destiné a fait partie de l’une des premières troupes folkloriques haïtiennes capables de proposer un spectacle rentable. Chanteur et danseur lors de rituels vodou, de famille lettrée mais proche d’un houngan (prêtre), il suivit des cours à l’école d’ethnologie de Port-au-Prince et obtint une bourse pour étudier le journalisme et la typographie aux États-Unis. Il commença alors une carrière de danseur à New York où il devint un ambassadeur de la culture de son pays. Destiné fonda une compagnie de musique/danse avec le fantastique percussionniste haïtien Alphonse Cimber et eut un succès immédiat. Après quelques années d’une belle carrière à la télévision, au cinéma et sur scène avec ses comédies musicales chorégraphiées, il enregistra un disque produit à New York par le jeune producteur Jac Holzman, qui réalisera nombre de séances de blues et de folk avant de lancer les Doors. Le flûtiste est sans doute le même que celui qui enregistra Calypso avec Harry Belafonte en 195627.

Émerante dite Emy de Pradines était la fille d’un poète, compositeur et auteur haïtien au nom de plume de Candio (Kandjo, du nom d’un célèbre chef marron jamaïcain vainqueur des troupes anglaises). La jeune femme fut imprégnée par cet environnement artistique et devint une chanteuse et danseuse passionnée par les musiques traditionnelles des campagnes où les plus anciennes coutumes vodou avaient lieu. Héritière du répertoire folklorique, elle a été enregistrée en 1953 pour les besoins d’un album paru à New York chez Remington, la marque de musique classique de Don Gabor (réédité par la suite par Concertum/Lafayette sous le nom de Moune de St. Domingue). La chanson dans le style « Dahomey » I Man Man Man est expliquée ainsi : au début du rite religieux, les loas sont appelés un par un tour à tour jusqu’à ce que l’un d’entre eux se manifeste.

Loa Azaou est une imprécation que les notes de pochette appellent « une longue et dramatique invocation à l’une des divinités les plus craintes de la magie noire — très ancien et traditionnel. Loa Azaou donne des blessures qu’on ne soigne pas, la mort et la destruction. Les dieux de la magie noire sont rarement invoqués et le sont seulement quand tous les autres dieux ont échoué. Dans cette chanson une prêtresse désespérée appelle ‘Azaou où es-tu, je te cherche, je n’ai ni famille, ni amis, je n’ai ni père ni mère, je viens de Guinée, Azaou où es-tu ?’ » (Azaou est aussi une localité du sud Niger).

Décrit comme un « mascaron », Mrélé, mrélé, mandé est également expliqué : « le plus rapide des pas vodou. Ceci est le cri de triomphe et de défiance d’une fille dont le père est un prêtre vodou et dont la mère est la prêtresse (mambo) du temple (hounfor) : ‘Aucun mauvais esprit ne peut me toucher — Je crie, je je hurle, je défie — aucun ne peut me faire de mal’ ». En termes d’architecture, un mascaron est un visage grimaçant sculpté sur une façade pour faire fuir les mauvais esprits. De Pradines chante ensuite Erzulie, déesse de l’amour.

Explorateur, journaliste, globe-trotter et écrivain, Maurice Bitter enregistra Cérémonies vaudou en Haïti sur le terrain : « Le Vaudou véritable est secret. Très rares ceux qui ont pu réellement l’approcher. J’eus cette chance au cours d’un séjour récent en Haïti. » Voodoo Drums provoqua la possession d’un adepte « chevauché » par un esprit. « L’être humain — le sexe importe peu — devient dieu. Il se transforme physiquement et moralement à l’image de ce dernier, crie, danse, prophétise, reste insensible à certains événements tels que la douleur ». Sur Nibo Rhythm, il commente : « La scène se déroule au milieu des danseurs habillés selon la qualité du « Loa » (dieu) appelé. Martelant le sol de terre battue de leurs pieds nus au rythme poignant des trois grands tambours. Drapeaux torsadés de rouge et or, poussière de rhum, allure des « montés » quelquefois par deux Loas qui se disputent le corps du patient, l’ensemble se déroule en une atmosphère prenante, sauvage et d’une réelle beauté ».

Petro Rhythm est une invocation à la loa Eloïse ; quinze femmes vêtues de blanc « psalmodient » sur Nago Rhythm où un grand nombre de danseurs (hounci-bossa et hounci canzos) participent pieds nus. Le prêtre chante et secoue sa calebasse « contenant des pierres et maintenue par un filet de vertèbres de serpent et de grains colorés ». Papa Legba, essentiel loa de la communication, du carrefour, ouvre la porte aux autres loas sur Papa Legba Invocation : « L’émotion croit et l’assistance semble en proie à un état de transe. Comme reliés par un fil invisible, les danseurs oscillant au rythme s’arrêtent net, statufiés dans les positions les plus invraisemblables à la pose, repartent à la seconde précise du déchaînement des tam-tams, titubants mais toujours avec des pas précis et purs, de plus en plus complexes. Le bruit des tambours devient ouragan. C’est le tonnerre avant l’éclair. Celui-ci jaillit avec la première danseuse chevauchée par le dieu. Sa démarche se précipite, son visage frémit, ses yeux se révulsent, l’écume emplit sa bouche. Semblable à une épileptique, elle va et vient en vacillant, maintenue par les adeptes qui en la déchaussant lui donnent un bâton. » Dahomey Rhythm est la base de la danse zépaule (zépol ou z’épaules). Les danseurs « en osmose avec le surnaturel » répondent aux questions sur l’avenir posées aux loas par l’assistance. Sur Mais Rhythm « Dans un coin de l’hanfor une petite hutte. C’est la « cage Zombi ». Un feu y brûle en un brasero au sein duquel chauffent à blanc deux pincettes. C’est le « feu Marinette », déesse antagoniste de la douce et chaude maîtresse Erzuli déesse de l’amour ». Zaca est le loa de la terre nourricière. Pendant cet enregistrement, la « visitée » dévora cinq calebasses de riz (« cinq kilos »). « Après la cérémonie, la jeune femme dégrisée réclama à manger : c’était Zaca, le dieu en elle qui l’avait dévoré. Pas son propre corps. »

Lire aussi le livret et écouter Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA 5375), qui détaille les influences du vaudou dans les musiques américaines et réunit des enregistrements de calypso, jazz, rock et blues évoquant cette religion28.

Bruno Blum

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2016

Merci à Frédéric David, Jean-Pierre Meunier et Philippe Michel.

1. Lire le livret et écouter Haiti - Meringue & Compas 1956-1962 (FA5615) dans cette collection.

2. Lire le livret et écouter Dominican Republic - Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450) dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret et écouter Puerto Rico - Plena & Bomba à paraître dans cette collection.

4. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Funk 1926-1962 (FA 5498) dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret et écouter The Roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962 (FA 5415) dans cette collection.

6. Lire les livrets et écouter les trois volumes de Boogie Woogie Piano 1924-1955 (FA 036, 164 & 5226) dans cette collection.

7. Vaudou, sous la direction de Michel Le Bris (Paris, Hoëbeke, 2003), p. 10.

8. Lire le livre et écouter le disque Africa and the Blues de Gerhardt Kubik (University Press of Mississippi, 1999).

9. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica Folk-Trance-Possession 1939-1961 (FA 5384) dans cette collection.

10. Lire le livret et écouter Bahamas Goombay 1951-1959 (FA 5302) dans cette collection.

11. Lire le livret et écouter Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5348) dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter Drums of Defiance: Maroon Music from the Earliest Free Black Communities of Jamaica, enregistré par Kenneth Bilby (Smithsonian Folkways, 1992).

13. Lire le livret et écouter Guadeloupe - Gwoka - Soirée lewoz à Jabrun (Ocora, 1992) et Velo - Gwoka (Esoldun 1963/1994).

14. Lire le livret et écouter Dominican Republic Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450) dans cette collection.

15. James Leyburn, The Haitian People (New Haven, USA, Yale University Press, 1941).

16. Melvin Jean Herskovits, The Myth of the Negro Past (New York, Harper & Brothers, 1941)

17. Lire le livret et écouter Great Black Music Roots 1927-1962 (FA 5456) dans cette collection.

18. Lire le livret et écouter Africa in America 1920-1962 (FA 5397) dans cette collection.

19. Melvin Jean Herskovits, Life in a Haitian Valley (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1937).

20. Lire le livre de 163 pages et écouter le coffret de dix disques Alan Lomax in Haiti (Hart, 2010).

21. Ganbo, gombey, goombay… on retrouve la même étymologie dans les tambours des marrons jamaïcains, le gombeh, le gumbo de Louisiane (l’okra, légume en forme de tambour conique) et les styles musicaux caribéens entendus dans Bermuda - Gombey & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA 5374) et Bahamas Goombay & Calypso 19511-1959 (FA 5302).

22. Freddi Williams Evans, Congo Square (New Orleans, University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2010. Édition française : Paris, La Tour Verte, 2012).

23. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Funk (FA5498) dans cette collection .

24. La première version enregistrée de « Bamboula » figure dans le coffret Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972, Musiques issues de l’esclavage aux Amériques (FA 5467, coédité par le musée du Quai Branly) dans cette collection.

25. Maya Deren, Divine Horsemen: the Divine Gods of Haiti (New York, Vanguard Press, 1953).

26. Le vaudou est une religion hénothéïste, un terme qui désigne une forme de croyance en une pluralité de dieux dans laquelle un ou plusieurs d’entre eux jouent un rôle prédominant et reçoivent à ce titre un culte préférentiel.

27. Écouter Harry Belafonte Calypso Mento Folk 1954-1957 (FA 5234) dans cette collection.

28. Lire aussi le livret et écouter Virgin Islands Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960 (FA 5403) dans cette collection.

Haiti Vodou - Folk Trance Possession - 1937-1962

Ritual Music from the First Black Republic

By Bruno Blum

This set, like its companion Jamaica Folk Trance Possession 1939-1961, provides precious evidence inherited directly from the days of slavery. It can be heard as a soundtrack that lends a tangible reality to obscure bygone centuries; apart from some rarities in Cuba and Jamaica there are no other records of authentic Caribbean rituals as ancient as these. Music from vodou religious ceremonies are the true source of non-religious forms such as Haitian meringue (a.k.a. mereng), born in the middle of the 17th century (a mixture of the French contredanse, Cuban danza and troubadours as well as the rhythms of Africa), and the konpa appearing in Port-au-Prince dancehalls at the end of the 1950s1. In turn, those Haitian styles became the roots of the fabulous Dominican merengue which evolved at the other end of the island2, and its descendants, like the bomba of Porto Rico3 (probably named after the Bumba Dance style heard here (CD1, track 19) and Salsa in New York. When slaves arrived in the Mississippi Delta, this ritual vodou music, together with that of Cuba’s santería, Lucumí (yoruba) orishas, Carabalí (Calabar) Abakuà secret society music, also nourished many Negro spirituals; they lie at the roots of ragtime, blues and New Orleans jazz, and consequently, funk4 and rock5. Music, however, is only one aspect of voodoo culture (spelled “vodu” in Dahomean, “vodú” in Cuba, “vaudou” in French, “vodou” in Haiti and “voodoo” in English). It is one of the essential means of entering into contact with its pantheon of deities, the loas or spirits, in trances where initiates are “mounted” (possessed) by the latter. These trances took place during the recording of Voodoo Drums and the possession song Agassou ma odé for example.

Music doesn’t lie. If something is to change in this world, it can only happen through music.

— Jimi Hendrix

Haitian Vodou

The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.

— Oscar Wilde

Music and dancing play a primary role in vodou: they stage the rituals which provoke trance. It is through dancing that vodou can best plunge into mysticism; the dancer’s physical movements are magic evocations of the visible world and they attract the divine. Divinities and spirits are invisible, like music, which shares this privilege with them.

Vodou in Haiti is a syncretism, in other words, it is a religious assembly of elements from several African religions. Slavery was carried out intensively in Haiti for a century, a much shorter time than the experience of its neighbours because French planters only really settled there in 1697 after reaching agreement with Spain. One hundred years later, after a long and painful revolution led by slaves, Haiti became the second country in the Americas to obtain its independence (1804), and abolished slavery before the rest of the world. It already possessed a particular Creole culture as a French colony, mixing various African cultures where animism figured prominently. Haitian vodou quickly became a real way of life, an identity… and a symbol of resistance. It was denounced by French slavers of course; they considered it diabolical and those who practised it were accused of sorcery. Banning such a form of worship evidently gave unity to the oppressed. And, as in santería in Cuba or in candomblé in Brazil, slaves disguised their rites with Catholic elements and, according to various criteria that were unexpected (if not plainly incongruous), they adopted Catholic saints corresponding to their own deities, the loas. These gods belong to families often determined by their polytheist African origins. In addition to the name of a saint, each loa has several patronymics, which contributes to the inextricable mystery formed by vodou rituals and mythology.

Voodoo in Africa

Different populations were carried off by French and Spanish slave-traders in the 17th century, and deported to the island which Columbus called Hispaniola (known to the French as Saint-Domingue.) Almost all the first captives came from Saint-Louis in Senegal: they were Wolof Muslims, Mandingo, Fula, Toucouleur or Bambara. Few in number, they left traces in Haiti where in 1950 people still addressed certain divinities in terms such as “salam” (the loas sinégal). Then came the captives bought on the former Slave Coast, where the King of Dahomey (the former kingdom is today in Benin) used to sell prisoners to Europeans. From this region came the term “vodu” used by the first native inhabitants of the Abomey plateau, the Gedevi people6. The word designates that which is mysterious, and therefore divine.

It is estimated that the African elements contained in Haitian music forms first took root among the peoples of this region (the current Ghana, Togo, Benin and Nigeria), and especially the great ethnic groups like the Akans (speaking the Twi language) as well as the Yoruba and Ibo populations. The people of Dahomey gave vodu its general structure. There are direct references to the Ibos of Nigeria in some titles (Ibo Dance, Ayanman Ibo, Ibo Dance Song, Ibo Dance), and also to the rites of the Yoruba people. Then in the 19th century different Bantu ethnic groups coming from the immense forests of today’s Cameroon, Angola and Congo brought their own spiritual traditions, transforming vodou and making it richer. With African cultures almost erased from the North American continent (direct ties with African music forms, jazz or American blues are tenuous7), it was the people of the Caribbean who contributed Afro-American Creole cultures, and vodou had the most influence.

Vodou is conceived as an immaterial force which exists everywhere in space, but which can be assigned a material point where initiates can call upon the loas with formulas that they alone know. A tree, rock or object becomes sacred during the time in which the divinity meets the possessed. The Gedevi people, on whom the King of Dahomey was waging war, were the principal victims of the slave trade. Captives were taken on the shores of today’s Benin, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and part of Angola. Many were christened by the Portuguese and had notions of Catholicism. These Christians would play an important role in the syncretism between animist and Catholic religions on Saint-Domingue. Religion always played a role of integration in African conflicts. The King of Dahomey welcomed conquered gods, and the conquered adopted the gods of the conquerors who were — logically — more powerful. Some of the countless spirits of these peoples’ ancestors were true gods and invocations were addressed to them in music; the fervent practise of religions became confused with the fervent practise of music.

Music is my religion.

— Jimi Hendrix

Haitian vodou music

If I don’t meet you no more in this world / Then I’ll meet you on the next one

And don’t be late / ‘Cause I’m a voodoo child / Lord knows I’m a voodoo child

— Jimi Hendrix, Voodoo Chile (Slight Return), 1968.

There are several types of vodou dances and they are associated with drum rhythms, which are themselves related to the nachons (nations) or religious groups using them in their rituals, each employing different instruments. The names of the principal nations and dances are also given to some of the titles here.

• Rada (three drums: the biggest is called manman, and can be a metre high; the segon is of average size and the smallest is the boula, on which quavers are played). The rhythms they play correspond to the rites known as Yanvalou, Yanvalou Dos-Bas, Yanvalou-Zépaule, Parigol, Fla Voudou, Nago, Mais/Mahi or Mayi (the Mahi ethnic group in today’s Benin), Daomé (Dahomey) etc. Rada drums play the rites and rhythms called Danwomen, Djapit, Ibo (Ibo Krabiyen, Ibo Iloukanman), Twarigol. The ogan is an iron bell which often accompanies the rhythm of Rada drums. The ason is sometimes present (a calabash wrapped in a net of pearl necklaces shaken in rhythm, found in Cameroon and in Nigeria’s agogo), together with an additional small bas (bass) drum.

• Nago: the Nago loas represent male potency and are associated with the Yoruba god of iron and fire, Ogoun/Ogun Feray (from the French “ferraille”, meaning with or of iron, i.e. ferrous metal). Their dances and rhythms, also called Nago, have a military aspect.

• Djouba: these, especially Azaka, are the loas of agriculture and bear a physical resemblance to peasants. Their roots lie deep in the island of Martinique. Rhythms and dances associated with them are: Baboul or Baboule (and its variants Baboul-Kase, Baboul Krabiyen, Baboul Woule etc.), Abitan, Djouba (or Juba) and “Matinik” (Martinique) rituals.

Rada, Nago and Djouba music share more similarities (cow-hide, hardwood, drumsticks, three drums with iron bars, a stricter, indeed tempered organization, and tempos in three) than the nanchons Petwo, Kongo, Ibo and Gedevi (Ghède), whose characteristics are different (goatskin, soft woods, two drums struck with the hands, informal music with tempos in two).

• Petwo (two little drums): the Petwo (or Petro) spirits are aggressive, protective, demanding and vivaciously quick; they represent the spirits of the first Haitian slaves (one of whose rebel chiefs was Jean Pedro, hence the name of the spirit) and the souls of the indigenous Taino Indians (Ayiti is the original Taino name of the island of Haiti). These loas were all invoked in the War of Independence in which Dessalines, the leader of the Haitian Revolution, vanquished the troops of Napoleon Ist in 1803. The dances and rhythms are named Petwo, Makiya or Makaya, Bumba, Kaplaw, Kitammoyé and Kita (Quitta).

• Kongo: these spirits, among them Kongo Zando and Rwa Wangol, are the ancestors of Bantus (in today’s Cameroon, Angola & Congo). Colourful and gracious, they love music, songs and dances, and their music is also performed on non-ritual occasions (Kalinda, Kongo Pile, Kongo Kaase, Kongo Siye, Kongo Lazil, Kongo Krabiyen, Kongo Larose).

• Ibo: the exacting Ibo spirits, including the voluble Ibo Lélé, come from the Ibo ethnic group which is situated in the south-east of today’s Nigeria. Their principal characteristic is pride, almost arrogance. In rituals, the souls of the possessed reside in sacred pots or kanaris controlled by spirits. The name Ibo is also given to the songs and dances of their nation.

• Ghède or Gède (Gedevi): the spirits of eroticism and death which control the cycle of life, including Ghède Nibo, Baron Lakwa Ghède Zarien. Like Baron Samedi, who is macabre, obscene and inhabits cemeteries, these loas play tricks on people and are represented by white faces on bodies dressed in black. Ceremonies generally end in Banda Ghèdes necromancer rites with their songs and dances played on Petwo drums (Banda is another ethnic group from Central Africa, and its music features elaborate polyrhythm). These frightening characters are also part of zombie legend.

Rituals Folk Trance Possession

Haiti has always suffered from political isolation due to its edifying history of revolution, and in the process of disrepute accompanying its ostracism, vodou was demonized. The country was long considered a bubbling cauldron of evil black magic populated by zombies and other monsters — even the Haitian elite believed it, not to mention the leaders of Haiti’s traditional adversaries in Saint-Domingue, the occupants of the other half of the island, who ostensibly scorned any and all cultures that were not European8.

CD1

In 1941 the great American anthropologist Melville Jean Herskovits published The Myth of the Negro Past9, a pioneering thesis which presented the concept of “race” as a socio-cultural rather than biological classification. His thesis was supervised by Franz Boas, a giant in modern anthropology who was one of the first to oppose the theories of scientific racism fiercely defended by the French politician and Minister Paul Bert, among others10. Herskovits spent time both in Dahomey and Haiti, and established a network of research into African and Afro-American culture which upset established ideas that Afro-Americans had lost their African cultural heritage in adapting to a new alien culture. In 1937 he published the essential Life in a Haitian Valley11 which gave a precise description of the day-to-day existence of vodou adepts; one of his students at the University of Columbia was Alan Lomax, a Texan and a philosophy graduate whose father John had already pioneered field recordings of folk music. Alan Lomax would become famous for his own field recordings made in the United States, a career whose beginnings coincided with Herskovits’ writings on vodou, and marked by Lomax’ own departure for Haiti when he was 21. Lomax stayed there for four months despite problems with malaria, the language, and the local secret police who were hostile to Americans. Between his arrival in December 1936 and his departure, Lomax made more than fifty hours of field recordings using a Thompson aluminium recorder and an RCA Velocity microphone.12 His equipment might have been archaic, and the quality less than satisfactory, but two of the young man’s historic recordings introduce this set.

Writer and ethnomusicologist Harold Courlander travelled to Haiti several times, fascinated by Africa’s legacy in the Americas; his novel The African (1967) told the story of a slave who sought to preserve his culture, and it was plagiarized in the Seventies by Alex Haley for the television series Roots. Herskovits, like Lomax, worked for the Smithsonian Institution where Courlander published (in 1952) the albums Folk Music of Haiti, Drums of Haiti and Songs and Dances of Haiti; the sound quality was better (it was recorded onto acetates, giving more faithful reproductions) and this anthology draws from those three historic albums.

La Famille li fait ça declares that the Ibo spirit Lazile is dancing and asks his family (i.e. followers) to do the same. Coté yo, coté yo (an Arada-Nago rite) is a dance inherited from the Benin ethnic group Mahi (or Mais). The song praises Sobo, the spirit protecting the hounfor or temple. As in Ganbos (track 17), in this song you can hear the sound of ganbos13 (a bamboo blocked at the end striking the ground). Ogoun Balindjo invokes the Yoruba god Ogun. The singer complains of her neighbour spying on her so that he can spread rumours about her; Ezilie Wédo invokes Erzulie, the loa spirit who is the wife of Damballah Wédo, and in this Arada-Nago ritual the spirit’s feelings of freedom are recalled: this female spirit is “no more in Africa” and can do as she wishes. The fragment Spirit Conversation was recorded during the trance of a houngan (priest) conversing with a loa and the spirits of his ancestors, whilst women comment on what he is saying. Moundongue yé yé yé is a song in the cycle of rites inherited from Mandingo/Mandinka ceremonies of worship in Equatorial Guinea and Congo. In 1952 the word “Moundongue” was an insult as Mandinka slaves were still held to be man-eating savages; the song describes the Moundongue loa’s meal after sacrificing a goat. Ou pas we’m innocent is a request for sentence to be passed by the spirit Ferei (Ogoun Ferraille), with the singer swearing his innocence. Goat-sacrifice is also an issue here. Général Brisé is a Kita spirit from Congo-Guinea to whom the performer sings that the land is in the hands of God.

Due to the American immigration of French planters fleeing the Haitian Revolution from 1791 onwards, a great number of Haitian slaves were taken to Louisiana, a French-speaking haven on the continent whose population were then predominantly Spanish Catholics or Anglo-American Protestants. The album Drums Of Haiti contains recordings of rituals whose sacred rhythms, played throughout the 19th century in Congo Square14 and during Mardi-Gras in New Orleans, are the roots of a number of 20th century Afro-American music forms, like jazz, merengue, salsa, funk, etc. These titles are essential clues15 to this, providing ancient testimony to this powerful Afro-Creole music culture which sprang up in the DNA of mutant forms of American music. Although music evolves everywhere, these ritual drums expressing ancestral ethnic customs certainly resemble those heard in the famous “bamboulas” held in the 19th century, embryos of the jazz in Congo Square. According to Courlander, Baboule Dance (three hand drums) is the same dance as the famous bamboula witnessed by travellers to islands elsewhere in the region during that period. The dance was linked with the Djouba rites coming from Martinique. The etymology of the word “Bamboula” (commonly attributed to the bamboo sticks used to strike the drums) probably dates back to that liturgical dance which in 1845 inspired a romantic play (by Louis-Moreau Gottschalk) entitled “Bamboula, danse des nègres.” This composition is an evocation of those rhythms heard in New Orleans, and it contributed greatly to demonstrate the originality of this composer (who later triumphed in Europe).16 It’s ironic that the written tradition of American music, until then considered a paltry by-product of European works, owed its letters patent of nobility to Gottschalk, whose opus was validated by European institutions and Chopin himself. The rhythm of Baboule Dance (and others heard here) belongs to the deep roots of a part of American jazz. In addition, the inspired vocal improvisations during certain trances are at the source of instrumental improvisations and “scat” vocals in jazz.

In 1950 Vodoun Dance was a fundamental liturgical vodou dance and Ibo Dance that of the Ibo ceremonies inherited from original Dahomean vodu. Petro Dance (Congo-Guinea ritual) is characteristic of this style, and Quitta Dance from the same region is an invocation addressed to the loa named Cymbi.

Congo Payette Dance (three hand drums) gave rise to a profane dance performed at carnivals, the “Congo-paille”. The “talking drum” sound called “tama” in the Wolof, Serere, Mandinka and Bambara languages, is obtained by sliding a finger over the drumhead to tauten or loosen it. In Vaccines you can hear the “bamboo trumpet”, the vaccine. The complex Bumba Dance rhythm (a Petwo rite) takes its name from the Bumba ethnic group, a Congo-Guinea nachon. Cé moin Ayida is an entreaty to the loa Ayida Wédo (in Dahomey’s pantheon), a symbol of the serpent on which the zépaule is danced, followed by Ayida Déesse arc-en-ciel, who metamorphoses into a serpent. Ayida Pas nan betise belongs to a Petwo rite different from the preceding one: Ayida is a quite different Petro loa. Mambo Ayida (Priestess Ayida) mentions (Equatorial) Guinea and Legba Aguator (the spirit of communication and the crossroads) is a member of the Ochan Nago vodou pantheon. It was not until the end of the war that the quality of field recordings progressed, with the arrival of magnetic tape beginning in around 1949. Recordings made in this way feature in the next disc.

CD2

The Jewish filmmaker of Ukrainian origin Eleanora Derenkowskaia — she took the pseudonym Maya Deren in America in 1943 — was one of the first ethnologists to study and document vodou ceremonies with films and recordings; beginning in 1947. She made some particularly remarkable field recordings like Creole o vodoun and Ayizan marche. An album of Maya Deren’s authentic ritual music recordings, Voices of Haiti, was published by Jac Holzman — the future discoverer of The Doors and Iggy Pop — and they are all included here. (N.B. Holzman would later go back to this music when he recorded at his own home the splendid album by Jean Léon Destiné included on CD 3). The rituals associated with this album appear alongside the titles. Also the authoress of one of the first reference books on the subject17, Maya Deren, a brilliant avant-garde director, made this comment on the philosophical meaning of vodou, its religious nature18 and the prejudice which discredited it:

“When a Haitian sings a song to a loa, he performs a mantra; the better he devotes himself to it body and soul, with discipline, the greater his reward. When he takes part in a lengthy ceremony he reaffirms his own principles: destiny, strength, love, life and death; he recapitulates his relation to his ancestors, to his history and to his contemporaries. He practises and formalizes his own integrity, his own personality, reinforces his disciplines and confirms his moral code. In a word, he comes out of it with a reinforced and refreshed sense of his relation to cosmic, social and personal elements. A person integrated in this way will probably function more efficiently, and this will be visible in the relative success of his projects. So the miracle, in a way, is an inner one. It is the performer who finds himself modified by the ritual; and consequently it is according to his inner change that the world will be different to him. Such is the nature of the blessing which supposedly rewards each religious devotee. If voodoo had not been so greatly maligned and misunderstood, or so confused with superstition and magic, all of that would be admitted and it would not be necessary to give details of its authentically religious nature here.”

— Maya Deren, notes for the album Voices of Haiti (Elektra, 1953).

1953 also saw the publication of the album, Voodoo - Authentic Music of Haiti, which alternated folk songs by Émerante de Pradines (CD3) and recordings of rituals. Three Rada drums are used in the title Drums. Over this Banda rhythm, partners danced without ever touching. Rasbodail Rhythm is played by an orchestra of drummers at a lively, rapid tempo; while it originated in India and was different from music with African roots, this style was integrated into Haitian culture, and musicians who practised vodou took part in performances of it.

Rituel vaudou en Haïti follows, where after three services invoking loas (Ogoun, Damballah Wédo and his spouse Ayida Wédo, Zaca), five titles are devoted to the ceremony bringing the offering of a ring to the loa of the sea (Ife), Agoué-Taroyo.

CD3

Jean Léon Destiné belonged to one of the first traditional Haitian folk troupes capable of putting on a profitable show, and he used to sing and dance at vodou ceremonies. The whole family could read and write but he was close to a houngan or priest. He went to the ethnology school in Port-au-Prince and obtained a scholarship to study journalism and typography in The United States, where he began a career as a dancer and became an ambassador for his country’s culture. Destiné founded a music & dance company with the fantastic Haitian percussionist Alphonse Cimber and they were immediately successful. After a fine career in television, film and theatre lasting several years with his musicals and choreographies, he made a record produced in New York by the young Jac Holzman, who was behind many blues and folk recordings before launching The Doors. The flute player is probably the same person who recorded Calypso with Harry Belafonte in 1956.19.

Émerante “Emy” de Pradines was the daughter of the Haitian poet, composer and author who signed his work as “Candio”. The young woman was heavily influenced by this artistic environment and became a singer and dancer with a passion for the traditional music of the countryside, where some of the most ancient vodou customs were still practised. Emy was recorded in 1953 for an album published in New York by Remington, the classical music label of Don Gabor (it was later reissued by Concertum/Lafayette under the name Moune de St. Domingue. The Dahoman-style song I Man Man Man explains that at the beginning of the religious ceremony, the loas are summoned one after another by name until one of them appears.

Loa Azaou is an imprecation which the sleeve-notes refer to as “a long and dramatic invoking of one of the most feared divinities in black magic”, a very ancient and traditional one. Loa Azaou causes wounds that cannot be healed: death and destruction. The gods of black magic are rarely invoked, and then only where all other divinities have failed. In this song a despairing priestess calls out, “Azaou, where are you? I’m looking for you. I have no family, no friends, no father and no mother. I come from Guinea, Azaou, where are you?” (The name Azaou is also given to a locality in the south of the Niger Republic.”)

Described as a “mascaron” or grotesque figure, Mrélé, mrélé, mandé is also “The fastest of the steps in voodoo. This is the cry of triumph and defiance of a girl whose father is a voodoo priest and whose mother is the priestess (mambo) of the temple: ‘No evil spirit can touch me, — I cry, I scream, I defy — no-one can hurt me’.” In architecture, this grotesque figure is carved into a façade to cause evil spirits to flee. De Pradines then sings Erzulie, the goddess of Love.

The field-recording Cérémonies vaudou en Haïti was made by explorer, journalist, globetrotter and author Maurice Bitter, who said, “True voodoo is secret. Very rare are those who have really come close to it. That good fortune was mine, in the course of a recent stay in Haiti.” Voodoo Drums provoked the possession of an adept “mounted” by a spirit. “Human beings — gender is of little importance — become gods. They are transformed physically and morally in the image of the latter; crying out, dancing and prophesying, they remain insensitive to certain events like pain.” For Nibo Rhythm he comments, “The scene takes place in the midst of dancers, dressed according to the standing of the loa they invoke, who stamp on the beaten ground with their bare feet to the rhythm of the three great drums. Twisted flags of red and gold, dust and rum, the allure of those who are ‘mounted’ by sometimes two loas fighting over the body of the patient… this all takes place in a compelling and wild atmosphere of real beauty.”