- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

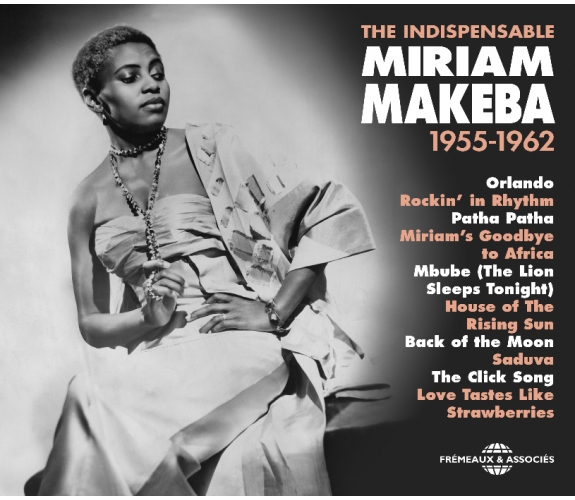

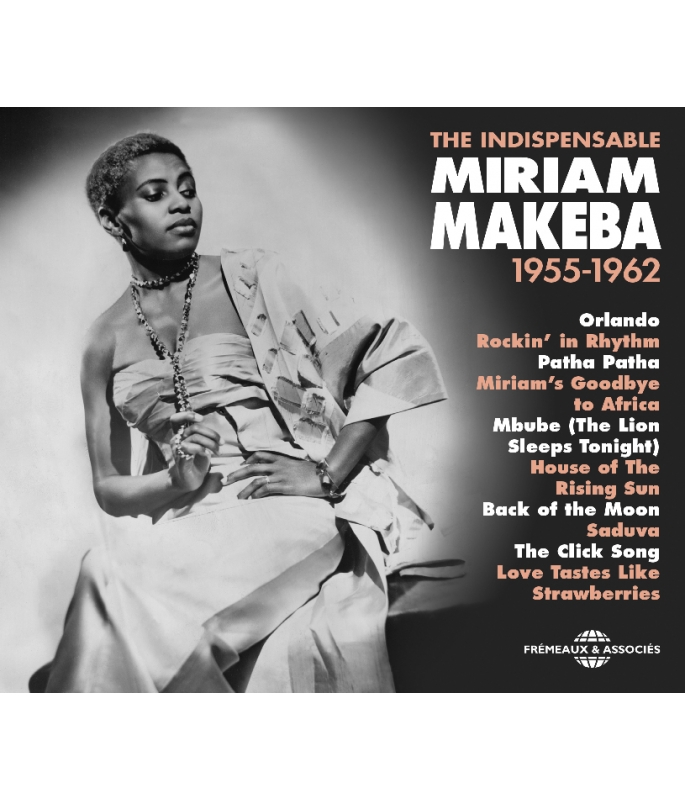

MIRIAM MAKEBA

Ref.: FA5496

EAN : 3561302549620

Direction Artistique : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 2 heures 52 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

Issue d’une famille très pauvre, Miriam Makeba est la première chanteuse africaine à avoir connu le succès en Amérique et en Europe. Mais avant son lancement à New York par Harry Belafonte, elle était déjà une grande vedette en Afrique du Sud.

Bruno Blum réunit et commente ici ses premiers enregistrements méconnus, gravés dans la misère et la terreur de l’apartheid, jusqu’à son triomphe américain qui fit d’elle un symbole international de résistance à l’oppression.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Ses mélodies inoubliables ont donné une voix à la douleur de l’exil et de la mise à l’écart qu’ell a ressentis pendant trente et une longues années. Pendant tout ce temps, sa musique a inspiré un puissant sentiment d’espoir en nous tous.

Nelson MANDELA

Known as Mama Africa, Miriam Makeba came from a very poor family and was the first African singer to achieve fame in America and Europe. But she was already a star in her native South Africa before Harry Belafonte launched her in New York. With a detailed commentary by Bruno Blum, this set presents her rare first recordings made during Apartheid, together with others leading to her triumph in America as an international symbol of resistance to oppression.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Her haunting melodies gave voice to the pain of exile and dislocation which she felt for thirty-one long years. At the same time, her music inspired a powerful sense of hope in all of us.

Nelson MANDELA

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : BRUNO BLUM

DROITS : DP / FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES.

CD 1 - APARTHEID IN JOHANNESBURG : THE MANHATTAN BROTHERS : LAKU TSHUNI ‘LANGA • TULA NDIVILE (SADUVA) • BABY NTSOARE. THE SKYLARKS • ORLANDO • OWAKHO • OLILILI • INTANDANE • PULA KGOSI SERETSE • KUTHENI SITHANDWA (DAY O) • NDIYA NXILA APHA E-BHAYI • BAYA NDI MEMEZA • VULU AMASANGO • UMBHAQANGA • NOMALUNGELO • TABLE MOUNTAIN • HUSH • MTSHAKASI • UTHANDO LUYAPHELA • PHANSI KWALOMHLABA • LIVE HUMBLE • SINDIZA NGECADILLACS • NDIMBONE DLUCA • NDAMCENGA • UNYANA WOLAHLEKO.

CD 2 - AFRICA’S QUEEN OF SOUL : ROCKIN’ IN RHYTHM • INKOMO ZODWA • EKONENI • DARLIE KEA LEMANG • SOPHIATOWN IS GONE • MAKE US ONE • BACK OF THE MOON • QUICKLY IN LOVE • MAKOTI • THEMBA LAMI • UYADELA • YINI MADODA • NDIDIWE ZINTABA • UILE NGOAN’ A BATHO • SIYAVUYA • PHATA PHATA • MIRIAM’S GOODBYE TO AFRICA. EXILE IN NEW YORK CITY : JIKELE MAWENI (THE RETREAT SONG) • SULIRAM • QONQONTHWANE (THE CLICK SONG) • UMHOME • OLILILI.

CD 3 - NEW YORK : LAKU TSHUNI ‘LANGA • MBUBE (THE LION SLEEPS TONIGHT/ WIMOWEH) • THE NAUGHTY LITTLE FLEA • WHERE DOES IT LEAD? • NOMEVA • HOUSE OF THE RISING SUN • SADUVA (TULA NDIVILE) • ONE MORE DANCE • IYA GUDUZA • KILIMANDJARO • ZENIZENABO • NTJILO NTJILO • UMQOKOZO • NGOLA KURILA • THANAYI THANAYI • LIWA WECHI • NAGULA • CARNIVAL (“ORFEO NEGRO” THEME) • NIGHT MUST FALL • LOVE TASTES LIKE STRAWBERRIES • CAN’T CROSS OVER.

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Laku Tshuni ‘LangaMiriam Makeba00:02:471955

-

2Tula Ndivile (Saduva)Miriam Makeba00:03:111956

-

3Baby NtsoareMiriam MakebaJoseph Mogotsi00:03:051956

-

4OrlandoMiriam MakebaJohanna Radebe00:02:471956

-

5OwakhoMiriam MakebaMiriam Makeba00:02:411956

-

6OlililiMiriam MakebaAlan Silinga00:02:351956

-

7IntandaneMiriam MakebaInconnu00:02:271956

-

8Pula Kgosi SeretseMiriam MakebaInconnu00:02:561956

-

9Kutheni Sithandwa (Day O)Miriam MakebaBurgie Irving00:02:371957

-

10Ndiya Nxila Apha E-BhayiMiriam MakebaMiriam Makeba00:02:301957

-

11Baya Ndi MemezaMiriam MakebaAbigail Kubeka00:02:281957

-

12Vulu AmasangoMiriam MakebaMiriam Makeba00:02:471957

-

13UmbhaqangaMiriam MakebaMiriam Makeba00:02:371957

-

14NomalungeloMiriam MakebaNomunde Sihawu00:02:251958

-

15Table MountainMiriam MakebaNomunde Sihawu00:02:251958

-

16HushMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:02:421958

-

17MtshakasiMiriam MakebaNomunde Sihawu00:02:191958

-

18Uthando LuyaphelaMiriam MakebaNomunde Sihawu00:02:281958

-

19Phansi KwalomhlabaMiriam MakebaNomunde Sihawu00:02:331958

-

20Live HumbleMiriam MakebaGigson Kente00:02:251958

-

21Sindiza NgecadillacsMiriam MakebaGigson Kente00:02:241958

-

22Ndimbone DlucaMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:02:281958

-

23NdamcengaMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:02:271958

-

24Unyana WolahlekoMiriam MakebaGigson Kente00:02:301959

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Rockin' in RhythmMiriam MakebaDuke Ellington00:02:521959

-

2Inkomo ZodwaMiriam MakebaGigson Kente00:02:261959

-

3EkoneniMiriam MakebaGigson Kente00:02:231959

-

4Darlie Kea LemangMiriam MakebaMary Rabotapi00:02:511959

-

5Sophiatown is GoneMiriam MakebaGigson Kente00:02:421959

-

6Make Us OneMiriam MakebaGigson Kente00:02:341959

-

7Back of the moonMiriam MakebaTodd Tozama Matshikiza00:03:011959

-

8Quickly in LoveMiriam MakebaTodd Tozama Matshikiza00:02:421959

-

9MakotiMiriam MakebaReggie Msomi00:02:361959

-

10Themba LamiMiriam MakebaReggie Msomi00:02:411959

-

11UyadelaMiriam MakebaAbigail Kubeka00:02:291959

-

12Yini MadodaMiriam MakebaMary Rabotapi00:02:351959

-

13Ndidiwe ZintabaMiriam MakebaGigson Kente00:02:331962

-

14Uile Ngoan A BathoMiriam MakebaMary Rabotapi00:02:321962

-

15SiyavuyaMiriam MakebaAbigail Kubeka00:02:401959

-

16Phata PhataMiriam MakebaReggie Msomi00:02:351959

-

17Miriam's Goodbye To AfricaMiriam MakebaReggie Msomi00:02:481959

-

18Jikele Maweni (The Retreat Song)Miriam MakebaTraditionnel00:02:341960

-

19SuliramMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:02:481960

-

20Qonqonthwane (The Click Song)Miriam MakebaMiriam Makeba00:02:331960

-

21UmhomeMiriam MakebaMiriam Makeba00:01:211960

-

22OlililiMiriam MakebaAlan Silinga00:01:221960

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Laku Tshuni ‘LangaMiriam MakebaAlan Silinga00:02:111960

-

2MbubeMiriam MakebaSalomon Ntsele00:02:331960

-

3The Naughty Little FleaMiriam MakebaThomas Norman00:03:451960

-

4Where Does It LeadMiriam MakebaG. Davis00:02:351960

-

5NomevaMiriam MakebaMiriam Makeba00:02:401960

-

6House Of The Rising SunMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:02:001960

-

7Saduva (Tula Ndivile)Miriam MakebaM. Dvushe00:02:321960

-

8One More DanceMiriam MakebaC.C. Carter00:02:441960

-

9Iya GuduzaMiriam MakebaMiriam Makeba00:02:121960

-

10KilimandjaroMiriam MakebaM. Dvushe00:02:491962

-

11ZenizenaboMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:01:241962

-

12Ntjilo NtjiloMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:02:291962

-

13UmqokozoMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:02:091962

-

14Ngola KurilaMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:03:101962

-

15Thanayi ThanayiMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:03:081962

-

16Liwa WechiMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:02:501962

-

17NagulaMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:01:381962

-

18Carnival (“Orfeo Negro” Theme)Miriam MakebaLuiz Bonfa00:02:251962

-

19Night Must FallMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:01:591962

-

20Love Tastes Like StrawberriesMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:03:261962

-

21Can't Cross OverMiriam MakebaTraditionnel00:03:191962

Makeba FA5496

THE INDISPENSABLE

Miriam Makeba

1955-1962

Rockin’ in Rhythm

Patha Patha

Miriam’s Goodbye to Africa

Mbube (The Lion Sleeps Tonight)

House of The Rising Sun

Back of the Moon

Saduva

The Click Song

Love Tastes Like Strawberries

The Indispensable MIRIAM MAKEBA 1955-1962

Par Bruno Blum

Ses mélodies inoubliables ont donné une voix à la douleur de l’exil et de la délocalisation qu’elle a ressentis pendant trente et une longues années. Pendant tout ce temps, sa musique a inspiré un puissant sentiment d’espoir en nous tous.

— Nelson Mandela, 2008.

Zenzi Miriam Makeba (4 mars 1932-9 novembre 2008) est née dans le township de Prospect à Johannesburg en Afrique du Sud. Son père était un Xhosa nommé Mpambane (nom officiel : Caswell Makeba) travaillant à des tâches administratives et sa mère une Swazi nommée Nomkomndelo (nom officiel : Christina) qui deviendra infirmière, sage-femme, guérisseuse (une isangoma aux pratiques divinatoires) et herboriste traditionnelle. Elle chantait parfois accompagnée au piano par Mpambane, qui composait en amateur. Avant sa nouvelle fille, Nomkomndelo avait déjà eu cinq enfants dont deux décédèrent en bas âge. Son sixième bébé était faible et malade, à la tête trop grosse. Nomkomndelo avait été prévenue qu’un nouvel enfant mettrait sa vie en danger et lors de l’accouchement difficile de la petite Miriam Makeba, la grand-mère répétait à sa mère «?uzenzile?», ce qui signifie «?tu ne peux t’en prendre qu’à toi-même?». La tradition voulait que les enfants reçoivent un prénom lié à la circonstance de leur naissance. À force d’entendre «?uzenzile?» la mère s’est mise à répéter ce mot au second degré. Elle déclara alors «?Je vais appeler ma fille Zenzi?».

Afrique du Sud

Si j’avais eu le choix, j’aurais certainement préféré être ce que je suis : une des opprimées plutôt que l’un des oppresseurs. Mais en vérité, je n’ai pas eu le choix. Et en ce triste monde où il y a tant de victimes, je suis fière d’être aussi une combattante.

— Miriam Makeba (1)

Zenzi dite Miriam Makeba naquit dans un contexte très difficile où la misère, l’ignorance, la maladie, les mauvais traitements et la violence étaient la norme. La terre d’Afrique du Sud est riche en diamants, en uranium, en pétrole, en or et en charbon : une véritable malédiction pour les peuples de cette région qui vivaient en harmonie avec la terre depuis des millénaires. C’est dans la violence que les Hollandais (mélangés à quelques Flamands et Allemands) ont colonisé l’Afrique du Sud à partir de 1652. Ils se sont appelés les Afrikaners, parlant la langue afrikaans dérivée du néerlandais de l’époque et commencèrent à y déporter des esclaves d’Inde, de Madagascar et d’Indonésie. Au cours des tyrannies de Louis XIII et Louis XIV et à la suite notamment de la révocation de l’édit de Nantes en 1685, des centaines de milliers de protestants persécutés ont fui la France. Certains de ces huguenots se sont réfugiés à Amsterdam d’où beaucoup s’embarquèrent pour l’Afrique du Sud, riche et prometteuse. Les Anglais sont arrivés ensuite, annexant la colonie des Afrikaners en 1806 après une guerre. Ils appelaient les Afrikaners du nom de «?boers?» (paysans en afrikaans). Les Afrikaners firent la guerre au peuple indigène xhosa de 1779 à 1879. Au fil du XIXe siècle les Zoulous, les Anglais, les Xhosa et les Afrikaners ont combattu pour le contrôle des territoires de la région. La découverte de diamants en 1867 et d’or en 1884 a fait redoubler les guerres meurtrières entre Britanniques et Afrikaners (les guerres des Boers, 1880-1881 et 1899-1902) qui ont mené à l’indépendance de l’Afrique du Sud en 1910. Les territoires concédés aux Noirs et Métis couvraient seulement 7% de la superficie du pays et la ségrégation raciale fut appliquée avec une violence aveugle. En 1931, la souveraineté totale du pays fut accordée par l’Angleterre sept ans avant la naissance de Zenzi, qui grandit à Nelspruit.

Apartheid

Au cours de la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale, après de nouvelles divisions entre Anglais et Afrikaners qui se détestaient, le régime de l’apartheid fut créé en 1948 par le parti nationaliste élu (par les Blancs anglais) qui créa trois catégories de citoyens : la minorité blanche (moins de 20?% de la population) contrôlait la majorité des Noirs et des Métis (et des Indiens), une tyrannie qui leur assura le meilleur niveau de vie de toute l’Afrique. Afrikaners et Anglais parlaient des langues différentes et se détestaient. Tandis que les Anglais gouvernaient et s’enrichissaient, les Afrikaners avaient des fonctions séparées, plus manuelles, comme policiers ou fermiers. Les personnes de sang africain étaient essentiellement cantonnées à des banlieues, les townships, d’où elles ne pouvaient sortir qu’avec des autorisations officielles afin de travailler dans les villes blanches (un passe non tamponné était puni de prison). Sans droit de vote, elles subissaient de graves discriminations en matière de revenus, d’éducation, de logement, d’espérance de vie et n’avaient presque pas accès à la médecine occidentale. Le fouet était une punition courante. La radio captant l’étranger, l’alcool — et même le hula hoop — étaient interdits. Soumis à une véritable armée d’occupation qui surveillait les townships et assurait (mal) l’absence de relations sexuelles entre Blancs et Noirs, les opprimés n’avaient aucun droit et leurs religions étaient combattues par le clergé chrétien blanc. Les rites animistes devaient rester cachés. Quand ils étaient démasqués, les informateurs noirs espionnant les Noirs étaient battus ou tués. La police ne protégeait pas les Noirs (tuer un Noir était sans grand risque) et la violence régnait dans les ghettos. Certaines personnes arrêtées ne sont jamais revenues. D’autres, dont deux des oncles de Zenzi, ont été envoyées à la guerre contre le nazisme et ne revinrent jamais. Comme aux États-Unis, les Noirs étaient représentés dans la presse comme des êtres inférieurs, païens, stupides et laids, ne pouvant s’améliorer qu’en essayant de copier les Blancs.

Musiques rituelles

Dans ces conditions proches de l’esclavage où les autochtones étaient littéralement parqués dans des ghettos insalubres et sans issue, les cultures traditionnelles tenaient une grande place. Les cultes des esprits multimillénaires fournissaient le socle d’une spiritualité participant à unir la population contre ce que le chanteur ivoirien de reggae Alpha Blondy décrirait dans sa chanson de 1985 «?Apartheid Is Nazism?».

«?La mort ne nous sépare pas de nos ancêtres. Les esprits de nos ancêtres sont toujours présents. Nous leur faisons des sacrifices et leur demandons conseil et direction. Ils répondent par les rêves ou par le biais d’hommes et de femmes médecins que nous appelons les isangomas.?»

— Miriam Makeba2

Zenzi n’avait que dix-huit jours quand sa mère fut arrêtée pour avoir vendu de l’alcool, une bière de malt et de maïs umqombothi qu’elle distillait en cachette, ce qui lui permettait de gagner quelques pence et d’améliorer la vie misérable de sa famille. Nomkomndelo fut jetée dans une prison afrikaner où elle purgea une peine de six mois, enfermée avec sa fille de quelques jours. Le père de Zenzi mourut d’une jaunisse quand elle avait cinq ans. La famille déménagea alors dans le hameau de Riverside près de Pretoria, plus au nord. Nomkomndelo était domestique et devait chaque jour aller travailler à Johannesburg en train. Quand ses parents étaient au travail, l’enfant en bas âge pouvait être laissée seule avec d’autres enfants plus âgés pendant des journées entières, enfermée dans la maison de briques surchauffée par le soleil. Avant les heures de travail de sa mère, la gamine dût travailler très tôt le matin dans la maison de terre battue où elle vivait avec ses vingt cousins : chaque jour l’enfant assurait cinq corvées d’eau, qu’elle remontait du puits située au bas de la colline dans une boîte de conserve de dix-huit litres qu’elle portait en équilibre sur la tête. Leur régime quotidien était la semoule de maïs, agrémentée parfois d’épinards, de cacahuètes, de potiron, parfois quelques fruits et d’autres légumes. Comme le sucre, le riz était un mets de luxe, consommé le dimanche avec, à l’occasion, une poule. Un jour, les enfants assistèrent à une descente de police afrikaner qui fit irruption chez eux en pleine nuit et arrêtèrent violemment un de leurs oncles dont le permis de déplacement n’était pas en règle.

Quel autre peuple est forcé à vivre comme ça ? Il doit y avoir les Juifs d’Allemagne et les peuples des pays occupés par les Nazis.

— Miriam Makeba (3)

Benjamine des cousins, Zenzi grandit dans une grande famille bienveillante et soudée, ce qui contrebalançait un peu la pauvreté et l’oppression permanente. Elle était élevée par sa grand-mère et ne pouvait voir sa mère, devenue cuisinière à la ville, qu’une fois par mois. Elle souffrait beaucoup de l’absence de sa mère, qui jouait de plusieurs instruments de musique (harmonica, lamellophone, tambours). Dotée d’une forte personnalité, d’une autorité naturelle et disposant de connaissances en herboristerie, Nomkomndelo avait le charisme d’un leader spirituel et l’assurance d’une résistante. Médium, elle pratiquait un mélange de médecine par les plantes et de spiritualité capable de capter et transmettre les énergies — et de commu-niquer avec les esprits. Le dimanche, la famille se réunissait souvent pour danser et chanter lors de cérémonies en souvenir des défunts proches de ce que Zenzi appelait «?l’Être Supérieur?». Les convives s’adressaient à leurs esprits afin qu’ils préparent l’arrivée des vivants. Ces rites étaient considérés païens par les Blancs, qui insultaient les pratiquants. Comme nombre d’opprimés afro-américains et africains, Zenzi avait été baptisée protestante et fréquentait le catéchisme le dimanche. Elle combinait tradition et présence au temple où elle chantait des cantiques chrétiens en afrikaans et en anglais comme «?Nearer, my God, to Thee?» de Sarah Fuller Flower ou «?Rock of Ages?» d’Augustus Toplady. Elle y entendait aussi des rythmes xhosa, zoulou et sotho. Fascinée par la musique, l’enfant était friande de la musique des Bapedi, une ethnie plus opprimée encore que les autres mais dont la musique était particulièrement sophistiquée et gaie. Ce paradoxe émerveillait l’enfant. Â l’âge de six ans environ, à force de chanter en chœur, seule à l’extérieur du bâtiment où avaient lieu les répétitions d’une chorale d’adultes où elle n’avait pas accès, Zenzi été admise dans la chorale tant elle chantait bien. Douée, passionnée, l’enfant devint une attraction, un exemple de feu sacré juvénile dans cette chorale de lycée qui interprétait des compositions sud-africaines, dont certaines hostiles au pouvoir — mais chantées en langues traditionnelles que les Blancs ne comprenaient pas. L’enfant était aussi privilégiée car elle allait à l’école, une pratique minoritaire relevant presque de la sédition— surtout pour une fille. L’école était déconseillée par les autorités pour qui l’obscurantisme était le meilleur moyen de garder les Noirs soumis. Zenzi y apprenait l’histoire d’Europe et rien sur l’Afrique. Elle devait parcourir huit kilomètres à pied chaque matin pour s’y rendre. Un soir au retour, la foudre a pulvérisé une des écolières avec qui elle courait pour s’abriter de la pluie. Elle gardera toute sa vie une peur panique des orages.

Oppression

À l’adolescence, sa tête prit des proportions normales et son corps se développa avec grâce. Dans l’après-guerre, la jeune Zenzi fréquentait surtout les garçons et des musiciens en particulier. Son frère Joseph lui fit découvrir le jazz. Rêvant d’Amérique où le succès était difficile mais pas impossible pour les musiciens noirs, elle admirait Lena Horne, Eartha Kitt, Pearl Bailey, Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan et Ella Fitzgerald qu’ils écoutaient le dimanche sur un gramophone à manivelle. Elle chantait passionnément ces chansons pour les copains de son frère et continuait à chanter dans la chorale quand elle entra au lycée, la Kilnerton Training Institution. Les chansons composées par des artistes locaux commentaient la situation sociale et comptaient bien plus que la propagande raciste des journaux et radios d’état. Accompagnant Zenzi en solo, la chorale interpréta le titre contestataire «?What a Sad Life for a Black Man?» pour le roi George et la princesse Elizabeth, mais leur voiture ne ralentit même pas à son passage. Une fois le sens de la chanson compris par les autorités, elle fut interdite. Le pianiste et directeur de la chorale, Joseph Mutuba, soutenait et encourageait la jeune femme. Avec le régime de l’apartheid instauré en 1948, des radios blanches ont été installées dans toutes les maisons et diffusaient 24h sur 24 de la propagande vantant les mérites du gouvernement sur fond de musique insipide. Déclarant alors que la population africaine était composée de «?Bantous?» donc d’immigrés sans droit sur la terre (ce qui était faux), le régime ferma presque toutes les écoles pour Noirs. À seize ans, Zenzi tomba amoureuse du beau Gooli (James Kubay) et dût quitter l’éducation pour travailler chez des Blancs. Elle y subit immédiatement des humiliations terribles. L’année suivante, elle céda à Goobi et tomba aussitôt enceinte alors que sa mère, gravement malade d’un pied infecté, était partie au Swaziland pour y subir une sorte d’exorcisme, un ukuthwasa, une formation destinée à lui enseigner comment évacuer les mauvais esprits amadlozi qui avaient pris possession d’elle. En 1950, après une mauvaise réception de la nouvelle par les familles, Zenzi se maria avec Gooli qui suivait une formation de policier loin de là et n’était présent auprès d’elle qu’un jour par mois. Après un accouchement très difficile, sa fille Bongi («?Je te remercie?») naquit en décembre. Souffrant d’un énorme abcès très douloureux, elle refusa l’ablation d’un sein à l’hôpital. Le médecin la jeta dehors en la traitant de païenne. Elle a finalement été guérie par une compresse de cactus appliquée par sa mère et rejoint la famille métis de son mari chez qui elle travailla très dur. Elle s’occupait du ménage, de la cuisine de la maison et de la production d’alcool prohibé organisée par sa belle-mère, qui la détestait et l’exploitait. Devenu un policier voué à réprimer les Noirs, son mari était violent et si jaloux qu’il enfermait la belle Zenzi quand il recevait des amis. La vie de Zenzi, qui n’avait aucun revenu malgré sa charge de travail, était devenue un cauchemar. Après le décès de son beau-père avec qui elle s’entendait bien, c’est sa sœur qui mourut en couches et bientôt le bébé de celle-ci. Quand elle découvrit que Gooli la trom-pait avec une autre de ses sœurs, celui-ci la battit très violemment. Au cours du passage à tabac, le bébé est tombé et a perdu du sang. À sa sortie d’hôpital, Zenzi est immédiatement retournée vivre chez sa mère, devenue entretemps une guérisseuse isangoma chevronnée après deux ans d’études. Elle lisait aussi l’avenir dans les os. Zenzi devint son assistante. Nomkomndelo lui transmit ses connaissances et Zenzi apprit à servir les esprits qui prenaient possession de sa mère au cours de transes récurrentes. Au cours de ces épisodes, Nomkomndelo dansait et chantait en différentes langues locales et s’exprimait en une glossolalie4 inintelligible, mystérieuse.

Manhattan Brothers

À la suite d’une vision, Nomkomndelo envoya Zenzi vivre à Johannesburg chez son riche cousin Sonti, propriétaire de plusieurs taxis. La grand-mère s’occupa de sa fille Bongi. Zweli, le fils de Sonti, était un dandy coquet. Il chantait dans les Cuban Brothers, un groupe de jazz amateur et engagea Zenzi comme chanteuse pendant deux années où elle apprit le métier. Ils interprétaient des succès américains très prisés dans les mariages, au temple et lors de bals populaires noirs. Le musicien Alan Silinga l’amena chez EMI où elle enregistra avec Joe Nofal (les enregistrements n’ont pas fait surface). Nathan Mdledle, le leader des Manhattan Brothers, un des groupes les plus célèbres du pays, la découvrit alors en concert au Donaldson Community Center d’Orlando East. Il lui proposa d’auditionner pour sa formation, qui avait besoin d’une chanteuse en remplacement d’Emily Kwenane. En 1953 Zenzi rejoint ce groupe professionnel, âgé de dix ans de plus qu’elle. Elle n’arrivait pas à croire sa chance mais les répétitions ont aussitôt commencé. Nathan Mdledle lui demanda d’utiliser son nom anglais Miriam Makeba comme nom d’artiste et les premières affiches parurent. Les Manhattan Brothers étaient un groupe vocal d’harmonies à cinq voix interprétant des titres des Mills Brothers et des Ink Spots, ce qui nécessitait une solide technique. Ils interprétaient aussi des chansons sud-africaines que Miriam enregistrerait des années plus tard. Peggy Phango, une de ses cousines, était chanteuse et comédienne (Cry, the Beloved Country, Zoltán Korda, 1951, avec Canada Lee et Sidney Poitier). Elle l’aida à mieux s’habiller et la forma à son nouveau métier. Très timide, Miriam s’abandonnait sur scène. Elle chantait et dansait avec tout son cœur, ce qui était critiqué par des gens malveillants choqués par la présence en scène d’une femme. Elle se produisait presque chaque soir dans des lieux souvent très mal famés des quartiers noirs du pays et loua une petite maison dans le township de Mofolo, au sud-ouest de Johannesburg. Elle gagnait très mal sa vie avec la musique, mais put héberger sa mère qui veillait sur sa fille.

Les Noirs n’étaient pas admis au syndicat des musiciens : c’est à cette époque qu’avec l’aide Manhattan Brothers ils osèrent créer leur propre syndicat et un centre culturel avec studio de répétitions, cours de musique et bureau, le Artist’s Union Center. Les Manhattan Brothers enregistraient pour la marque Gallotone, qui payait un cachet de deux livres et demie par musicien pour une séance de quatre titres et ne versaient ni redevance ni droit d’auteur. Fondé en 1926 par Eric Gallo, Gallotone était initialement un magasin de disques qui distribuait la marque américaine Brunswick en Afrique du Sud. Gallo ouvrit un studio en 1932 et engagea un chercheur de talents noir, Griffith Motsieloa, qui se chargea de la réalisation artistique. Sa marque eut un quasi monopole pendant près de vingt ans dans le pays, produisant des classiques comme le célèbre Mbube («?Le Lion est mort ce soir?») de Solomon Linda5 que Miriam Makeba reprend ici (disque 3). Les morceaux étaient créés spontanément sur place et enregistrés sur le champ «?avant qu’on ne les oublie?». En 1955, Gallo demanda à Miriam Makeba, présentée comme «?Le Rossignol, la beauté intelligente qui chante avec les Manhattan Brothers?», d’enregistrer son premier disque sous son nom. Composé en xhosa, Laku Tshuni ‘Langa chante un homme assis dans le soleil couchant. Son amour a disparu :

Je te chercherai partout/Dans les hôpitaux, les prisons/Jusqu’à ce que je te trouve/Car tandis que le soleil se couche, je ne cesse de penser à toi

Ce fut un tel succès que Gallotone demanda à Miriam d’en enregistrer une version anglaise. La chanteuse n’aimait pas les nouvelles paroles, qui font allusion à une femme trompant son homme et dénaturent la beauté originelle du morceau. Mais elle a été contrainte de chanter ce « Lovely Lies?», un nouveau succès (il fut même le premier disque sud-africain classé aux États-Unis, n°45 du Billboard en mars 1956). En conséquence, Gallo produira d’autres disques d’elle en anglais (elle fut l’une des premières Sud-Africaines noires à le faire), dont Hush, une réflexion sur la mort et Make Us One, sur l’exil rural et un rêve d’unité. Sophiatown is Gone (1959) fait allusion à un quartier noir rasé par les autorités à partir du 9 février 1955 afin de faire place à la construction de maisons pour Blancs, ce qui occasionna l’expulsion de près de 60.000 personnes. C’est là que vivaient le futur archevêque Desmond Tutu, le trompettiste Hugh Masekela et l’un des rares avocats noirs du pays : Nelson Mandela. C’est aussi à Sophiatown pendant la démolition que Lionel Rogosin, un cinéaste américain blanc, indépendant et engagé, réalisa en secret un film long métrage d’«?ethnofiction?» sur une famille noire sud-africaine vivant la tragédie de l’apartheid (Come Back, Africa, 1959). Prétextant le tournage d’un documentaire commercial sur la musique noire, il avait obtenu avec grande difficulté les autorisations de tourner. En 1957, il proposera à Miriam Makeba de participer au film dont le titre était emprunté à l’hymne de l’ANC, le parti de Mandela qui luttait courageusement contre la dictature. Miriam enregistrait surtout en xhosa, comme ici sur Saduva où elle évoque un enfant qui s’est mal conduit et rejette la faute sur la mauvaise influence d’un autre enfant. Comme sur Saduva et Olilili (lamentation d’une femme délaissée par son mari et essayant de rassurer son enfant affamé), une seconde version de ce titre a été enregistrée plus tard aux États-Unis dans un style très différent. Ces deux versions montrent ici l’évolution de Makeba : tout en gardant la verve et la culture du ghetto, elle maîtrisait aussi le jazz, qui l’inspirait.

The Skylarks

À vingt ans, la chanteuse était déjà une vedette dans son pays. Domestique le jour, le contraste entre son dur quotidien et sa célébrité était difficile à supporter. Après son premier succès sous son nom début 1956, en raison de la concurrence de la marque Troubadour et des Quad Sisters qui vendaient très bien chez Trutone, Sam Allock (le chercheur de talents noir de Gallo) demanda à Miriam de former un groupe vocal féminin — tout en continuant à l’enregistrer avec les Manhattan Brothers. S’il existait bien une tradition locale de groupes de femmes, l’idée était surtout de capter une partie du succès des Américaines blanches les Boswell Sisters (Nouvelle Orléans), qui dans les années 1930 enregistraient dans le difficile style «?close harmony?» des Ink Spots/Mills Brothers. Elles furent copiées dans les années 1940-50 par des groupes états-uniens comme les Andrew Sisters et les McGuire Sisters, qui étaient connues en Afrique du Sud. C’est avec l’orpheline Mary Rabotapi (quatorze ans) et Mummy Girl Nketle (remplacée en 1957 par Abigail Kubeka) que Miriam forma les Sunbeams («?les rayons de soleil?») également appelées les Skylarks («?les alouettes?», leur nom de scène). Bonnes chanteuses, elles étaient aussi capables de composer des mélodies très originales. Avec elles, Miriam Makeba menaçait la suprématie de la chanteuse vedette Dolly Rathebe. Inkomo Zodwa et Hush ont compté parmi leurs grands succès. Gibson Kente leur écrit plusieurs autres titres dans cette veine, dont Make Us One.

Les voyages du groupe étaient sujets au harcèlement policier et à de rudes humiliations. Par jeu, des goujats afrikaners policiers exigèrent que le groupe chante sur le bord de la route en pleine nuit. Bien qu’ils aient toujours été en règle, ils passèrent plusieurs fois le week-end en prison. Miriam rencontra à cette époque Nelson Mandela, un de ses admirateurs venu l’écouter avec des membres de l’African National Congress. Le groupe avait du succès et partit en tournée en bus au Lesotho, au Mozambique, au Zimbabwe et jusqu’au Congo où ils dormirent parfois au bord des routes, en pleine jungle. Miriam y découvrit des panneaux publicitaires à son effigie vantant les mérites d’un soda.

Un soir de 1956 près de Volkhurst, la troupe subit un grave accident de la route. Deux Blancs furent tués dans leur voiture, un autre amputé. Dans la camionnette gisaient quatre enfants et tous les musiciens sérieusement blessés, Miriam y compris. Plusieurs d’entre eux étaient inconscients. Il y avait du sang partout. Arrivée huit heures plus tard, la police ne les a pas aidés, préférant les menacer d’une arme car ils les considéraient responsables. Ils prirent leurs couvertures et couvrirent les morts qu’ils ont emmenés, abandonnant les blessés gémissant dans la douleur de leurs fractures, en rase campagne, dans le froid, en pleine nuit. Ils n’ont même pas envoyé de secours. Ce n’est que dans la matinée que des Suisses de passage emmenèrent Miriam à la ville. L’hôpital pour Blancs refusa tout soin et la jeta dehors. Elle finit par trouver un hôpital pour Noirs qui ne possédait pas de véhicule et dut louer un camion pour aller chercher les survivants à trente kilomètres de là. Après un cauchemar de deux jours et deux nuits, Miriam a finalement pu aller chez Gallotone chercher des voitures qui ont emmené les blessés à Jo’Burg. Le célèbre comédien Victor Mkhize est mort de n’avoir pu obtenir de soins à temps. Miriam commentera : «?J’ai regardé le génocide dans les yeux?».

Phata Phata

«?C’est étrange mais la chanson qui a poussé ma carrière plus loin que tout, celle qui m’a fait connaître de gens dans des pays où l’on ne me connaissait pas auparavant est aussi l’une de mes chansons les plus insignifiantes. J’ai écrit «?Pata Pata?» en Afrique du Sud en 1956. C’est une petite chanson marrante, avec un bon rythme. Je l’ai inventée comme ça un jour en pensant à une danse de chez nous. «?Pata?» signifie «?toucher?» en zoulou et en xhosa. La version originale a été un succès en Afrique du Sud.?» La version de 1959 incluse ici est en fait une composition différente sur le même thème et épelée Phata Phata. En 1967, une chanson homonyme avec des paroles en anglais figurera sur son premier album pour Reprise aux États-Unis, un des premiers grands succès internationaux interprétés par une Africaine.

African Jazz and Variety

En 1956, une fois sa blessure à la hanche guérie, Miriam, Abigail et Mary rejoinrent la African Jazz and Variety Revue pour une tournée de dix-huit mois. Leur succès fut sans précédent dans le pays. Le spectacle était organisé par Alfred Herbert, un Juif qui organisa les premiers spectacles noirs de qualité du pays et les présenta aux Blancs en les offrant ensuite aux Noirs, à bas prix, un jour par semaine. Il contribuait ainsi à lutter contre le racisme institutionnel en invitant des artistes noirs dans des salles prestigieuses réservées aux Blancs, comme le Town Hall de Johannesburg. C’est en voyant Miriam, qui brillait sur scène, que Lionel Rogosin décida de la filmer. Elle chanta deux chansons pour lui, tournées dans un shebeen (bar de fortune où l’alcool était vendu malgré la prohibition) en pleine nuit pour ne pas être dérangés. Ces images aussi splendides que rares montrent le talent et la beauté de Miriam. Rogosin lui promit de l’inviter aux États-Unis pour la promotion du film. En attendant, en raison de l’impossibilité d’accéder aux restaurants toujours réservés aux Blancs, la chanteuse mangeait des boîtes de conserve froides en tournée. Une nuit, la police découvrit une arme appartenant à un musicien indien dans le bus de la revue. Toute la troupe a été jetée en prison. Miriam y passa une semaine seule dans une cellule. Puis elle devint amie avec Dorothy Masuka, la vedette n°1 du pays depuis le début de la décennie — sa chanteuse préférée qui était en tête d’affiche de la revue. Elle enregistra ensuite quelques titres très influencés par Ella Fitzgerald (Back of the Moon, Quickly in Love) avec cette revue jazz américaine, mais jamais avec Masuka, sous contrat avec EMI. À force de travail (Miriam était très exigeante), en 1958 les Skylarks étaient devenues le groupe n°1 du pays. Leur style mi-américain mi-sud-africain était original et frais.

En 1956-1959 Miriam vécut ouvertement avec Sonny Pillay, une vedette de la chanson sud-africaine d’origine indienne en tournée avec elle dans la revue. C’était la première fois qu’un couple de célébrités s’affichait en dépit de leurs origines différentes. Issue de l’esclavage, la grande communauté indienne d’Afrique du Sud subissait également la ségrégation raciale, séparée des Blancs comme des Noirs. Les Indiens étaient considérés supérieurs aux Noirs, qu’ils avaient tendance à mépriser, mais ce n’était pas le cas de Pillay6.

King Kong

Miriam Makeba joua ensuite le rôle de Joyce, la petite amie du champion de boxe Ezekiel Dlamani, dit King Kong, dans l’une des premières comédies musicales sud-africaines incluant des Noirs. Joyce y jouait la reine du Back of the Moon un bar à alcool de Sophiatown qu’elle évoquait (la chanson devint un de ses grands succès), et Quickly in Love. La pièce était basée sur la vie tragique du boxeur et contenait des pièces musicales écrites par Todd Matshikiza, un journaliste du magazine noir Drum and News (et rédacteur en chef du Golden City Post) sur des paroles de Pat Williams. La pièce avait été écrite par Leon Gluckman et était produite par Harry Bloom, deux Juifs que Miriam appréciait. Selon elle, bien que Blancs, les Juifs avaient souvent une attitude différente, non (ou beaucoup moins) raciste. Elle n’était pas obligée d’appeler son nouveau producteur «?baas?» (boss en afrikaans) et de baisser les yeux comme avec la plupart des autres Blancs. Gluckman s’arrangeait pour détourner les lois de l’apartheid (ils jouaient dans des universités où la ségrégation raciale était impossible), ce qui permit à la mère de Miriam d’assister au spectacle. L’histoire était aussi inspirée de la vie de Jake Tule, un champion sud-africain qui, autorisé à jouer un combat à Londres, y tua un Blanc. Pour cette raison, d’autres visas de sortie lui furent ensuite refusés par les autorités, ce qui brisa sa carrière. Comme lui, King Kong ne fut pas autorisé à quitter le pays malgré son talent. Brisé, le champion sombra dans l’alcool, commit un meurtre et fut assassiné en prison. Nathan Mdledle, le leader des Manhattan Brothers, jouait le rôle de Kong et Joe Mogotsi (un autre chanteur du groupe) celui de son frère. Dans la troupe figurait aussi un trompettiste de vingt ans, Hugh Masekela, que Miriam connaissait depuis qu’il avait fréquenté la Huddleston Boys School. Le jeune homme avait appris la trompette grâce à un prêtre nommé Huddleston, qui lors d’un voyage aux États-Unis avait obtenu un don d’instruments de jazzmen américains. Lors de la première de King Kong en février 1959, les billets du spectacle étaient déjà vendus pour les six prochains mois. À vingt-sept ans, Miriam Makeba était l’une des grandes vedettes d’Afrique du Sud. Sa mère prédit dans une vision qu’elle allait quitter le pays. Sonny lui annonça alors qu’il la quittait pour poursuivre sa carrière à Londres : car contrairement à lui (il était d’origine indienne), Miriam ne pouvait obtenir de passeport en raison de sa couleur. Quelques jours plus tard, en raison d’une grossesse extra-utérine, elle s’écroula devant l’hôpital : noire, elle fut refusée aux admissions. Sa mère dût l’emmener à vingt-cinq kilomètres de là, à l’hôpital pour Noirs où elle fut sauvée in extremis. Après un long rétablissement et un premier voyage en avion (les Noirs ne prenaient jamais l’avion) pour jouer au Cap, où Miriam fut très gênée d’être assise parmi les Blancs, la nouvelle tomba : deux ans après la fin du tournage Come Back, Africa était enfin projeté en Europe et les critiques adoraient le film. Miriam y était très remarquée et Rogosin parvint à l’inviter au Festival de Venise. Il lui obtient un passeport contre la promesse d’un départ très discret — et peut-être un peu de corruption de fonctionnaire. Miriam enregistra plusieurs titres dont «?Iphi Dlela?», Phata Phata et Miriam’s Goodbye to Africa la veille de son départ. Les deux morceaux ne seraient publiés que plus tard — avec succès. Miriam laissa sa famille et ses amis sans leur dire au revoir. Seules sa fille Bongi et sa mère étaient au courant. Nomkomndelo reçut un message de l’esprit préféré de Miriam, Mahlavezulu, qui était formel : elle ne reviendrait jamais. Pourtant son retour serait triomphal — mais trente et un ans plus tard, en 1990.

Londres

Dans l’avion plein, aucun Blanc ne s’assit à côté d’elle. Elle disposait de toute la place. Après un long voyage où elle observa, perplexe, la non-ségrégation, le traitement d’égalité qu’elle reçut dans les restaurants d’aéroports, elle arriva à Paris où, pleine de doutes, elle prit le train pour Aix-en-Provence où l’accueillit le réalisateur. Il lui annonça qu’elle était invitée dans le Steve Allen Show, l’un des plus importants spectacles télévisés. Mais Miriam n’avait jamais vu de télévision, interdite aux Noirs dans son pays et ne se rendit pas compte de l’importance de cette nouvelle. Rogosin lui décrocha aussi un engagement au Village Vanguard à New York. Miriam traversa la France en voiture. Voir des Blancs creuser des tranchées en plein été lui coupa le souffle : elle n’a jamais vu ça chez elle. À Venise, tout le monde la remarqua. Les Noirs étaient très rares en Italie et elle était une attraction. Une petite foule la suivait dans la rue. Les starlettes en maillot de bain étaient moins remarquées qu’elle pourtant elle restait habillée (elle ne savait pas nager !). Miriam Makeba n’arrivait pas à le croire : elle était très attendue. Le film reçut le Prix de la Critique. Elle retrouva Sonny peu après à Londres, où elle restera trois mois. Elle se maria impulsivement avec Sonny Pilay, qu’elle quittera à son tour. Comblée, le 15 septembre 1959 elle fut invitée dans In Town Tonight à la télévision BBC où elle chanta Back of the Moon, son nouveau succès, ce qui tombait pile le lendemain du vol soviétique Luna 2, le premier à s’écraser victorieusement sur la lune. Une de ses idoles, la grande star américaine et activiste du mouvement de libération noir Harry Belafonte la vit à la télé et courut à sa rencontre le lendemain lors d’une projection du film. Belafonte arrangeait tout : un visa pour les États-Unis, son passage chez Steve Allen… il devint de fait son manager. Depuis son excellent album Calypso de 1956, le chanteur et sex symbol jamaïcain/new-yorkais proche de Martin Luther King était devenu l’une des rares grandes vedettes noires des États-Unis7.

Africa in America

Miriam Makeba est arrivée à New York le 28 novembre 1959. Accueillie par Belafonte qu’elle appelait son Grand Frère, elle devait y ouvrir une série de concerts cinq jours plus tard — et chanter dans le Steve Allen Show à Los Angeles entretemps. Belafonte fournit toute son équipe : couturier, arrangeur, bureaux… Accueillie comme une vedette en Californie, elle répéta «?Intoyam?» pour NBC TV. Très nerveuse, c’est sur un nouvel arrangement américain qu’elle interpréta sa chanson indigène, qui était incluse dans le film. De retour à New York, on lui demanda des autographes dans un magasin de chaussures. À la première au Village Vanguard, Belafonte avait invité des gens qu’elle admirait : l’actrice Diahann Caroll, l’acteur Sidney Poitier. Nina Simone, Duke Ellington et Miles Davis étaient aussi présents. Très impressionnée et timide dans une salle comble, elle chanta Jikele Maweni (The Retreat Song), Back of the Moon, Qonqonthwane qui sera connue sous le nom de The Click Song (cette chanson festive chantée dans les mariages évoque une fiancée rêveuse et contient les fameux ‘clics’ d’une consonne unique au xhosa), «?Seven Good Years?» — une chanson en yiddish que lui enseigna la mère de son producteur Alfred Herbert — et Nomeva (une chanson d’amour tribale) en rappel. Son originalité fit sensation et Miriam, incrédule, fut assaillie par les journalistes. Craignant pour sa famille, elle refusait de parler politique. En quelques jours, elle conquit les États-Unis. Après quatre semaines au Village Vanguard, elle fut engagée huit semaines au Blue Angel, un endroit branché pour new-yorkais sophistiqués. Elle était admirée par Lauren Bacall, Bing Crosby, LizTaylor, Sarah Vaughan… et demandait des autographes à toutes ces célébrités qui l’approchaient (comme promis elle en envoyait à sa cousine restée en Afrique du Sud). Elle vit son idole Ella Fitzgerald sur scène et comble du bonheur, parvint à faire venir sa fille de neuf ans à New York. Bongi fut couverte de cadeaux à son arrivée. Miriam signa avec les disques RCA, qui rachetèrent son contrat avec Gallotone pour $45.000 qu’elle dût rembourser : elle ne toucha pas un sou sur son premier album.

Elle refusait tout maquillage et laissa ses cheveux courts pousser librement. Elle refusa de suivre la mode en les défrisant ; elle inventa ainsi la coiffure «?afro?» bientôt adoptée par les Afro-américains de la soul puis du funk, etc.

L’Afrique était soudain à la mode. L’album Drums of Passion du percussionniste nigerian Babatunde Olatunji parut le 15 février 1960 avec succès. C’est lors d’un engagement à Chicago que Belafonte lui apprit que sa mère Nomkomndelo, dite Christina, était décédée. Voulant rentrer à Johannesburg pour voir sa tombe, elle se présenta au consulat d’Afrique du Sud où son passeport fut tamponné «?non valable?» : son succès était perçu comme une insolence. La chanteuse était désormais apatride, forcée à l’exil et risquait la prison si elle rentrait — ce qui était maintenant impossible. Entretemps, l’armée tira sur la foule lors d’une manifestation dans son pays. Deux de ses oncles furent tués lors d’un massacre de plus, à Sharpeville le 21 mars 1960. Peu à peu, malgré sa timidité, consciente de l’importance de son accès aux médias, Miriam s’engagea dans le mouvement des Droits Civiques et participa à des conférences de presse, tenues avec Belafonte en ouverture de leurs concerts, où ils partageaient l’affiche. Elle y rapporta les horreurs du régime de son pays, mises en parallèle avec la réalité des lois de ségrégation «?Jim Crow?» du sud des États-Unis8. Son amitié avec le chanteur et son épouse Julie s’approfondit encore.

Harry l’invita sur scène quand il chanta triomphalement à Carnegie Hall le 2 mai 1960, une semaine avant l’enregistrement de l’album Miriam Makeba pour RCA. Paru pendant l’été, le vinyle 30cm présentait ces chansons traditionnelles dans un style nouveau. Américanisées avec mesure, elles transmettaient un sentiment d’authenticité — et de talent au service de la justice. L’album se vendit bien. Son éclectisme est remarquable : ambassadrice indigène d’un monde colonisé, Miriam y inclut des chansons traditionnelles indonésienne (Suliram), autrichienne (One More Dance), américaine (House of the Rising Sun qui évoque un bordel de la Nouvelle-Orléans) mais aussi sud-africaines en xhosa, swazi et zoulou (sur cette dernière elle est pionnière de l’enregistrement multipiste avec trois voix superposées). Enregistré avec les musiciens de Belafonte (dont elle avait adapté le Day O en xhosa en 19579), il contient une chanson folk jamaïcaine, The Naughty Little Flea de Lord Flea10 évoquant une puce qui visite les recoins les plus érotiques du corps.

En plus de ses concerts où la ségrégation raciale l’empêchait, comme chez elle, de dîner dans la plupart des restaurants du sud (ses choristes blancs du Chad Mitchell Trio étaient admis dans les hôtels, mais pas elle !), elle partit en tournée triomphale avec Harry Belafonte tout l’été 1961, alternant conférences et chant. Elle apprit beaucoup de son mentor afro-jamaïcain. À la suite du référendum du 31 mai 1961, l’Afrique du Sud devint une république et la reine Elizabeth II perdit son titre de reine du pays. Infatigable militante de la libération de son peuple, Miriam Makeba emménagea dans un quatre pièces de la 97e rue sur Central Park avec sa fille. Elle appréciait Randy Weston, Carmen McRae, Nina Simone et Sarah Vaughan. Elle participa à différents concerts caritatifs pour l’Afrique et finança même un appartement pour le trompettiste Hugh Masekela, venu étudier à la Manhattan School of Music. Il contribua à l’album suivant (ils se marieront en 1964).

Son deuxième et influent album11, le magnifique The Many Voices of Miriam Makeba parut au printemps 1962. Il accentuait encore sa démarche interna-tionale, réunissant une lamentation congolaise, une ballade inca, un titre chanté en brésilien repris du film Orfeo Negro, du calypso caribéen et plusieurs airs d’Afrique du Sud réarrangés au goût du jour (la traduction de plusieurs titres de chansons est disponible dans la discographie). L’artiste rencontra et chanta ses succès sud-africains Mbube et Nomeva pour John Kennedy, qui l’invita au gala donné pour son anni-versaire le 19 mai 1962. Elle fut suivie de Marilyn Monroe qui y interpréta son fameux «?Happy Birthday Mr. President?». En exil sans passeport, elle fondit en larmes en recevant un passeport tanzanien du président Julius Nyerere. Miriam chanta en soutien des Mau Mau au Kenya et en Tanzanie fraîchement indépendante. Elle était devenue la voix de l’Afrique toute entière. Après plusieurs incarcérations et procès, l’avocat et leader de l’African National Congress, Nelson Mandela, fut incarcéré le 5 mai 1962. Il ne sortirait de prison que vingt-huit ans plus tard, quand les lois de l’apartheid furent abolies. Miriam fit alors un retour très émouvant dans son pays. En 1994, Mandela devint le premier Noir élu en Afrique du Sud.

Bruno BLUM

Merci à Bob Gruen, Åke Holm et Alexis Frenkel.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

1. MAKEBA, Miriam, HALL James, My Story, autobiographie : New York, Plume/Penguin, 1989.

2. MAKEBA, Miriam, HALL James, ibid.

3. MAKEBA, Miriam, HALL James, ibid.

4. En anglais «?speaking in tongues?».

5. La version originale de «?Mbube?» par Solomon Linda et les Evening Birds est incluse dans notre anthologie Africa in America 1920-1962 (FA 5397) dans cette collection.

6. L’avocat et futur président indien Mohandas «?Mahatma?» Gandhi passa vingt et une années de sa vie en Afrique du Sud, où il lutta pour le bien-être des communautés indienne et africaine. Sa pensée non-violente évolua dans ce pays, où il purgea des peines de prison et prit goût à la politique. Il deviendra à la fin du XXe siècle un héros national d’Afrique du Sud.

7. Lire le livret et écouter Harry Belafonte 1954-1957 (FA 5234) dans cette collection.

8. Lire le livret et écouter Slavery in America – Redemption Songs 1914-1972 (FA 5467) dans cette collection.

9. Deux versions jamaïcaines de «?Day O?» parues avant celle de Belafonte sont disponibles, l’une par Louise Bennett sur Jamaica – Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) et l’autre par Edric Connor.

10. La version originale de «?Naughty Little Flea?» par Lord Flea est disponible sur Calypso 1944-1958 dans notre coffret Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde (FA 5342) dans cette collection.

11. Comme pour deux titres de Babatunde Olatunji, «?Umqokozo?» sera plagié par Serge Gainsbourg, qui en fera sa chanson «?Pauvre Lola?» parue sur Gainsbourg Percussions en 1964.

The Indispensable MIRIAM MAKEBA 1955-1962

By Bruno Blum

“Her haunting melodies gave voice to the pain of exile and dislocation which she felt for thirty-one long years,” said Nelson Mandela when she died in 2008. “At the same time, her music inspired a powerful sense of hope in all of us.”

Zenzi Miriam Makeba (March 4, 1932–November 9, 2008) was born in Prospect, a township in Johannesburg, South Africa. Her father was a Xhosa named Mpambane (officially Caswell Makeba) who worked in administration, and her mother a Swazi named Nomkomndelo (officially Christina) who became a nurse, midwife and healer—an isangoma or soothsayer—who also studied plants. She sometimes sang accompanied on piano by Mpambane, an amateur composer. Before her new daughter was born, Nomkomndelo had already given birth to five children, two of whom died young. Her sixth baby was weak and ill, her head too large. Nomkomndelo had been warned that a new child would put her life in danger, and when she was giving birth to little Miriam, her own mother kept repeating uzenzile to her, meaning, “You have only yourself to blame…” According to tradition, children were given a first name linked to the circumstances of their birth. Hearing uzenzile, Nomkomndelo began repeating the word, not taking it literally, and said, “I’m going to call my daughter Zenzi.”

South Africa

“Given the choice, I would have certainly preferred being what I am: one of the oppressed, rather than an oppressor. But in truth, I didn’t have that choice. And in this sad world where there are so many victims, I am proud to be a fighter also.” Miriam Makeba.1

Zenzi, called Miriam Makeba, was born in a very difficult context: misery, ignorance, sickness… harsh treatment and violence were commonplace. The South African soil was rich in diamonds, uranium, oil, gold and coal: a genuine curse for those people who had been living in harmony with the earth for thousands of years. Violence reigned when the Dutch (mixed with Flemish and German people) began colonizing South Africa in 1652. They called themselves Afrikaners because they spoke Afrikaans, derived from the Dutch language of the period, and they began deporting slaves to South Africa from India, Madagascar and Indonesia. Under the tyranny of the French monarchs Louis XIII and Louis XIV, and notably after the Edict of Nantes revocation in 1685, hundreds of thousands of Protestants fled persecution in France. Some of these Huguenots took refuge in Amsterdam, where they embarked for rich and promising South Africa. The English arrived later and annexed the Afrikaners’ colony in 1806 after a war. They called Afrikaners “Boers” (the Afrikaans word for peasants). The Afrikaners warred against the indigenous Xhosa people from 1779 to 1879. In the course of the 19th century, Zulus, the British, Xhosas and Afrikaners would fight to control the region. The discovery of diamonds in 1867, and gold in 1884, caused carnage in wars between the Afrikaners and the British (the Boer Wars in 1880-1881 and 1899-1902 led to South Africa’s independence in 1910.) Blacks and people of mixed race were granted territories that covered only 7% of the country’s surface, and racial segregation was blindly enforced with violence. In 1931, England granted the country total sovereignty: it came seven years before Zenzi was born. She grew up in Nelspruit.

Apartheid

In the course of the Second World War, and after new divisions between the British and the Afrikaners—they hated each other—an apartheid regime was established in 1948 by a nationalist party (elected by the British) and three categories of citizens were created: the white minority (less than 20% of the population) controlled a majority of Blacks and mixed-race people together with Indians, under a tyrannical rule which guaranteed the minority the highest standard of living in the whole of Africa. Afrikaners and British citizens spoke different languages and detested each other. While the British governed and became rich, the Afrikaners had separate, more manual roles as policemen or farmers for example. People with African blood were confined to townships which they could leave only with official approval, in order to work in white cities (any person with an unstamped permit was imprisoned). People from the townships had no voting rights and were subjected to discrimination—in earnings, education and housing, with impact on life expectancy—and they had almost no access to western medical care. The whip was a common punishment. Listening to radio stations outside South Africa was prohibited, and alcohol, even hula hoops, were forbidden. Under what appeared to be an army of occupation, which monitored the townships and tried (in vain) to ensure there were no sexual relations between Whites and Blacks, the oppressed had no rights and their religions were fought against by the white Christian clergy. Animist rituals had to remain hidden. When black informants spying on their kin were unmasked, they were beaten or killed. The police did not protect Blacks (killing a black man was almost without risk), and violence reigned in the ghettos. Some of those arrested never returned home. Others, including two of Zenzi’s uncles, were sent off to war against the Nazis; they never returned. As in The United States, Blacks were represented in the press as inferior beings, stupid, ugly heathens who could only better themselves by trying to copy Whites.

Ritual music

In a context close to slavery—native populations were literally parked in unsanitary ghettos from which no escape was possible—traditional cultures were of major importance. Spirit-worship and rites several thousand years old provided a basis for a spirituality which contributed to unite the population in the struggle against what Ivory Coast reggae singer Alpha Blondy would describe in his 1985 song, “Apartheid Is Nazism.”

“… Death does not separate us from our ancestors. The spirits of our ancestors are ever-present. We make sacrifices to them and ask for their advice and guidance. They answer us in dreams or through a medium like the medicine men and women we call isangoma.”

— Miriam Makeba2

Zenzi was only eighteen days old when her mother Nomkomndelo was arrested for selling umqombothi, a beer made from malt and corn which she brewed in secret to earn a few pennies and make the life of her family less miserable. Nomkomndelo and her baby were thrown into an Afrikaner prison for six months. Zenzi’s father died of jaundice when she was five, and the family moved north to the small village of Riverside near Pretoria. Nomkomndelo took the train every day to work in Johannesburg as a domestic servant. When her parents were at work, the child Zenzi would be left alone with older children for whole days, shut inside a brick house heated by the burning sun. Before her mother’s working-hours, the young girl had to get up very early every morning in the clay-walled house where she lived with twenty cousins: she had to fetch water five times every day, drawing it from a well at the bottom of a hill and carrying it in an eighteen litre can balanced on her head. Their daily diet was corn-flour, sometimes mixed with spinach, peanuts or pumpkin, sometimes fruit and other vegetables. Rice, like sugar, was a luxury meal eaten on Sundays, occasionally with chicken. The children once witnessed Afrikaner police raid the house in the middle of the night and violently arrest one of their uncles whose travel-permit wasn’t valid.

“What other race is forced to live like that? It must be the Jews in Germany and the people in countries occupied by the Nazis.”

— Miriam Makeba 3

Zenzi, the youngest cousin, grew up in a large, united, kindly family, which compensated (a little) for the permanent oppression and poverty. She was raised by her grandmother and could only see her mother, now a cook, once a month. Her mother played several instruments—harmonica, lamellophone, drums—and Zenzi suffered from her absence. Nomkomndelo had a strong personality; she had natural authority, a wide knowledge of plants, and the charisma of a spiritual leader combined with the confidence of a resistant. As a medium she practised a mixture of plant-medicine and spirit-worship; she was capable of transmitting energies and communicating with the spirits. On Sundays the family often gathered to dance and sing at ceremonies in remembrance of the deceased who were close to what Zenzi referred to as the “Superior Being.” Those present talked to their spirits in order to prepare the coming of the living. These rites were considered pagan by Whites, who insulted this religion’s followers. Like a number of oppressed Africans and Afro-Americans, Zenzi had been baptised a Protestant and regularly went to Sunday school. She combined tradition with church attendance, singing Christian hymns (in Afrikaans and English) like Sarah Fuller Flower’s “Nearer, my God, to Thee” or Augustus Toplady’s “Rock of Ages”. In church she also heard Xhosa, Zulu and Sotho rhythms. Fascinated, the child loved the music of the Bapedi people, an ethnic group even more oppressed than the others, but whose music was particularly cheerful and sophisticated. The child marvelled at this paradox. When she was six, after singing in chorus alone outside the building where an adult choir was rehearsing (she wasn’t allowed inside), Zenzi was finally permitted to join them because she sang so well. Gifted, and with a passion for music, she became an attraction, a symbol of the juvenile religious fire of this high-school choir singing South African compositions, some of which opposed the regime; but they were sung in traditional languages which Whites didn’t understand. The child was also privileged because she went to school; it was a minority-practice close to sedition, especially for a girl. Schooling was discouraged by the authorities: obscurantism was the best way for them to ensure Blacks remained submissive. Zenzi learned the history of Europe, and nothing of African history. She had to walk five miles every morning to attend classes. On her return home one day, a school-friend was struck by lightning as they ran to take shelter from the rain. For the rest of her life, Zenzi would panic whenever there was a storm.

Oppression

When she was in her teens, her head resumed normal proportions and her body developed gracefully. Post-war, the young Zenzi kept regular company with boys and especially musicians. Her brother Joseph introduced her to jazz. Dreaming of America, where success didn’t come easily even though it wasn’t impossible for black musicians, she admired Lena Horne, Eartha Kitt, Pearl Bailey, Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald, listening to them on Sundays on a wind-up gramophone. She passionately sang for her brother’s friends, and continued singing in the choir when she went to high-school at Kilnerton Training Institution. The songs written by local artists were social commentaries, and they counted for much more than the racist propaganda of the state’s newspapers and radio.

Accompanying Zenzi singing solo, the choir would sing the protest song “What a Sad Life for a Black Man” for King George and Princess Elizabeth on a royal visit, but their car didn’t even slow down as it passed them by. Once the authorities understood the meaning of the song, it was banned. Joseph Mutuba, the choirmaster and also the choir’s pianist, gave encouragement to Zenzi. After the establishment of the apartheid regime in 1948, white radio was introduced in every house, and its propaganda was broadcast twenty four hours a day, vaunting the government’s merits against an insipid musical background. After declaring that the African population was composed of “Bantus”, and therefore of immigrants who had no land-rights (which was untrue), the regime closed almost all the schools for Blacks. At sixteen, Zenzi fell in love with the handsome Gooli (James Kubay), and had to forgo her education and work for Whites. She was immediately subjected to terrible humiliation. The following year, she gave in to Gooli’s advances and became pregnant at once, just when her mother fell seriously ill with a foot-infection; Nomkomndelo went to Swaziland to undergo a kind of exorcism known as ukuthwasa, a training aimed at teaching her how to evacuate the evil amadlozi spirits which had taken possession of her body. In 1950, after their families had received the (bad) news, Zenzi married Gooli; he trained to become a policeman far away from home, and was only at Zenzi’s side for one day each month. Zenzi’s daughter Bongi (it means “Thank you”) was born in December after a difficult delivery. Suffering from an enormous abscess and in extreme pain, Zenzi refused the removal of one of her breasts; her doctor threw her out of the hospital, calling her a heathen. She was finally cured by a cactus poultice applied by her mother, and returned to her husband’s mixed-race family where she was put to work. She did the cleaning and cooking, and also distilled the illicit alcohol produced by her mother-in-law, who hated and exploited her. Gooli became a policeman committed to Black repression, and was so violent and jealous that he locked Zenzi up when friends came to the house. The life of Zenzi, who was penniless despite working herself to the bone, became a nightmare. She was treated decently by her father-in-law, but first he passed away, and then her sister died giving birth to a baby who soon died, too. When Zenzi discovered Gooli’s infidelity with one of her own sisters, she was given a violent beating; her daughter Bongi also fell during her mother’s struggle with her husband and began bleeding. When Zenzi came out of hospital she returned to live with Nomkomndelo, by now an expert isangoma healer after two years of study. She could also see the future by interpreting bones, and Zenzi became her assistant; Nomkomndelo passed on her knowledge and Zenzi learned to serve the spirits who took possession of her mother in repeated trances. During these episodes, Nomkomndelo would dance and sing in different local dialects that were unintelligible and mysterious.4

The Manhattan Brothers

After having a vision, Nomkomndelo sent Zenzi to live in Johannesburg with her rich cousin Sonti who owned several taxis. The grandmother took care of Bongi. Sonti’s son Zweli was a fashion-conscious dandy who sang with the Cuban Brothers, an amateur jazz group, and they hired Zenzi as their singer for two years while she learned the trade. They played American hits that were in demand at weddings, in church, and at dances that were popular with Blacks.

Musician Alan Silinga took her to EMI where she recorded with Joe Nofal (the recordings have never come to light). Nathan Mdledle, the leader of the Manhattan Brothers, one of the most famous groups in the country, discovered Zenzi at a concert held in Donaldson Community Center, Orlando East, and asked her to audition for his band, which needed a singer to replace Emily Kwenane. In 1953 Zenzi joined this professional group (it was ten years older than she was), not believing her luck, but rehearsals began straight away. Nathan Mdledle asked her to use her English name Miriam for concerts, and the first posters appeared with the name Miriam Makeba. The Manhattan Brothers were a five-piece vocal harmony group whose repertoire contained songs by the Mills Brothers and the Ink Spots, which made a solid technique necessary; they also sang South African numbers that Miriam would record years later. Peggy Phango, one of her cousins, was a singer and actress (Cry, the Beloved Country, dir. Zoltán Korda, 1951, with Canada Lee and Sidney Poitier) and she helped Miriam to dress better as well as coaching her in her new trade. Although extremely shy by nature, Miriam completely abandoned herself to the stage, singing and dancing wholeheartedly… so much so that she was unkindly criticized by those who were shocked by the presence onstage of a woman. Miriam appeared almost every night in the country’s black districts (often in disreputable venues), and she rented a little house in Mofolo township southwest of Johannesburg. Music paid badly but it was a living, and Miriam had a roof for her mother to take care of Bongi.

Blacks weren’t admitted to the musicians’ union, and it was in this period that, with the help of the Manhattan Brothers, they dared to create their own union, and set up a cultural centre with rehearsal studios, music lessons and an office: the Artists’ Union Centre. The Manhattan Brothers recorded for Gallotone, which paid each musician two and a half pounds for a four-title session, but no royalties or copyrights. Founded in 1926 by Eric Gallo, Gallotone was initially a record-shop distributing records on the American Brunswick label in South Africa. Gallo opened a studio in 1932 and hired a black talent scout, Griffith Motsieloa, to be responsible for the label’s artists. Gallotone enjoyed a quasi-monopoly in the country for almost twenty years, producing classics like the famous Mbube (“The Lion Sleeps Tonight”) by Solomon Linda,5 which Miriam Makeba sings here on CD3. The songs were created spontaneously in the studio and recorded there and then, “before we forgot them.” In 1955 Gallo asked Miriam Makeba, introduced as “The Nightingale, the intelligent beauty who sings with the Manhattan Brothers”, to make her first record under her own name. Composed in Xhosa, Laku Tshuni ‘Langa is the song of a man seated in the setting sun. His lover has disappeared: “I will come looking for you everywhere / in the hospitals, in the jails / until I find you / because as the sun goes down, I can’t stop thinking of you.”

It was such a hit that Gallotone asked Miriam to record an English version of it, but she disliked the new lyrics: they told the story of a woman cheating on her man, and distorted the original beauty of the piece. But she was obliged to sing “Lovely Lies”, a new hit; it was even the first South African record to be placed in the U.S. charts (N°45 in ‘Billboard’ in March 1956). As a consequence, Gallo would produce other English-language records made by her (Miriam was one of the first black South African women to do this), including Hush, a reflexion on death, and Make Us One, which deals with rural exile and dreams of unity. Sophiatown is Gone (1959) is an allusion to a black district razed to the ground by the authorities, beginning on February 9th 1959, to make way for houses for Whites. It entailed the expulsion of some 60,000 people. The place was where future Archbishop Desmond Tutu lived, together with trumpeter Hugh Masekela and one of the country’s rare black lawyers, Nelson Mandela. During its demolition, Sophiatown was also where Lionel Rogosin, a white American independent filmmaker and activist, secretly made an “ethno-fiction” feature-film dealing with a black South African family living through the tragedy of apartheid (Come Back, Africa, 1959). Under the pretext of shooting a commercial documentary on black music, Rogosin obtained a film-permit with great difficulty. In 1957 he would offer Miriam Makeba the chance to appear in a film whose title was borrowed from the anthem of the African National Congress [ANC, Mandela’s party], which was bravely fighting the dictatorship. Miriam mostly recorded singing in Xhosa, as here on Saduva where she evokes a child who has behaved badly and throws the blame on another child. As with Saduva, a second version of Olilili (the lament of a woman abandoned by her husband and who tries to comfort her starving child), was recorded later in the USA in a quite different style. The two versions here show how Makeba was evolving as a singer: while preserving the verve and culture of the ghetto, she was also mastering the jazz idiom which provided her inspiration.

The Skylarks

At the age of twenty the singer was already a star in her country. A domestic servant by day, the contrast between this harsh existence and celebrity was difficult to bear. After her first hit under her own name in 1956, and due to the competition of the Troubadour label and the Quad Sisters who were selling well for Trutone, Sam Allock (another of Gallo’s talent scouts) asked Miriam to form a female vocal group and also continue to record with the Manhattan Brothers. There was already a local girl-group tradition, but the idea now was to capitalize on the success of the Boswell Sisters, a white American group from New Orleans who recorded in the Thirties in the difficult “close harmony” style of the Ink Spots and the Mills Brothers.

The Boswell Sisters were copied in the 40’s and 50’s by other American groups like the Andrews Sisters and the McGuire Sisters who were known in South Africa. And so Miriam formed the Sunbeams, also known as the Skylarks onstage, with the fourteen-year-old orphan Mary Rabotapi and Mummy Girl Nketle (who was replaced in 1957 by Abigail Kubeka). They were good singers and also capable of composing highly original melodies. Together with the two girls, Miriam Makeba threatened the supremacy of star singer Dolly Rathebe. Inkomo Zodwa and Hush were among their great hits, and Gibson Kente wrote several other titles for them in the same vein, among them Make Us One.

The group’s travels were subjected to police harassment, humiliation and crudeness. Churlish Afrikaner policemen even made them sing by the roadside in the middle of the night as a kind of game… The group was always above reproach yet they spent a weekend in prison on several occasions. It was during this period that Miriam Makeba met Nelson Mandela, an admirer who went to listen to her with members of the ANC. The group was a success, and went on tour by bus to Lesotho, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, even as far as the Congo, sometimes sleeping by the roadside in the middle of the jungle... where Miriam was surprised to see her effigy on posters advertising a soft drink.

One evening in 1956, the troupe was involved in a serious road accident near Volkhurst. Two Whites were killed in their car and another had to be amputated; in the troupe’s van, four children and all the musicians lay seriously injured, Miriam included, with several of them unconscious. There was blood everywhere. The police arrived eight hours later but nobody helped them; they were even threatened with a gun because the police held them responsible for the accident. The police took their blankets and covered the dead before carrying them away, abandoning the injured, their fractures untreated, to fend for themselves in the middle of the night. The police never called for assistance. Miriam wasn’t taken to hospital until the following morning, when Swiss travellers who happened to be passing by stopped to help. The hospital—reserved for Whites—refused care and threw Miriam out. She finally found a Black hospital, but they had no vehicle and she had to hire a truck to fetch the other survivors some twenty miles away. After a nightmare lasting two days and two nights, Miriam was finally able to reach Gallotone and obtain cars to take the injured to Johannesburg. The famous comedian Victor Mkhize died because he didn’t receive treatment in time. Miriam commented, “I’ve looked genocide in the eye.”

Phata Phata

“It’s strange, but the song that pushed my career farther than anything, the one that made me known to people in countries where I wasn’t known before, is also one of my most insignificant songs. I wrote ‘Pata pata’ in South Africa in 1956. It’s a funny little song with a good rhythm. I invented it just like that one day when I was thinking about one of our dances. ‘Pata’ means ‘to touch’ in Zulu and in Xhosa. The original version was a hit in South Africa.” The 1959 version included here is in fact a different composition based on the same theme, with the spelling Phata Phata. In 1967 a song of the same name with words in English would appear on her first album for Reprise in The United States, one of the first great international hits sung by an African woman.

African Jazz and Variety

In 1956, once her injured hip had healed, Miriam, Abigail and Mary joined the African Jazz and Variety Revue for an eighteen-month tour. Their success throughout the country was unprecedented. The Revue was organized by Alfred Herbert, a Jew who staged the first black shows of quality in South Africa, first for white audiences, and then for Blacks (at cheaper prices) once per week. It was his contribution to the struggle against institutional racism, and he invited black artists to appear in prestigious venues hitherto reserved for Whites, like Johannesburg’s Town Hall. It was when he saw Miriam, a sparkling stage performer, that Lionel Rogosin decided to film her. She sang two songs for him, filmed in a shebeen [a makeshift bar where alcohol was sold despite the ban] in the middle of the night so that they wouldn’t be interrupted. His images, as splendid as they are rare, demonstrate the talent and beauty of Miriam. Rogosin promised to invite her to the United States to promote the film. In the meantime, it remained impossible for her to enter a restaurant—they were still reserved for Whites—and so the singer ate cold food out of tins while she was on tour. One night, police searched their tour bus and discovered a weapon belonging to an Indian musician. The whole troupe was thrown into jail. Miriam spent a week alone in a cell.

She would find a friend in Dorothy Masuka, the country’s N°1 star since the beginning of the decade; she was Miriam’s favourite singer and topped the bill for the Revue. Miriam went on to record a few titles with a strong Ella Fitzgerald influence (Back of the Moon, Quickly in Love) with members of the Jazz Revue, but never made a record with Masuka, who was under contract to EMI. After a great deal of hard work (Miriam was very demanding), in 1958 the Skylarks became South Africa’s N°1 group. Their style, half-American, half-South African, was original and fresh.