- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

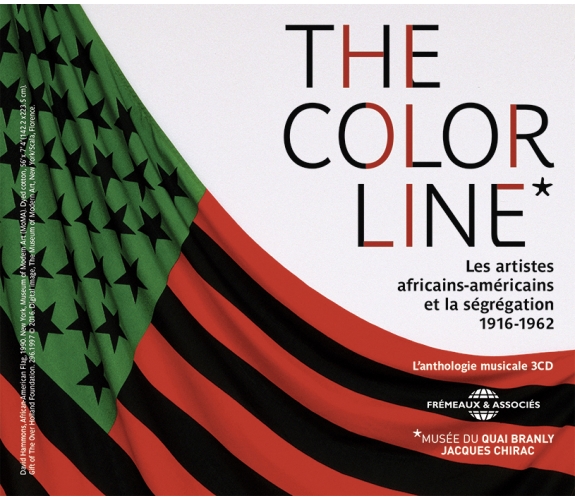

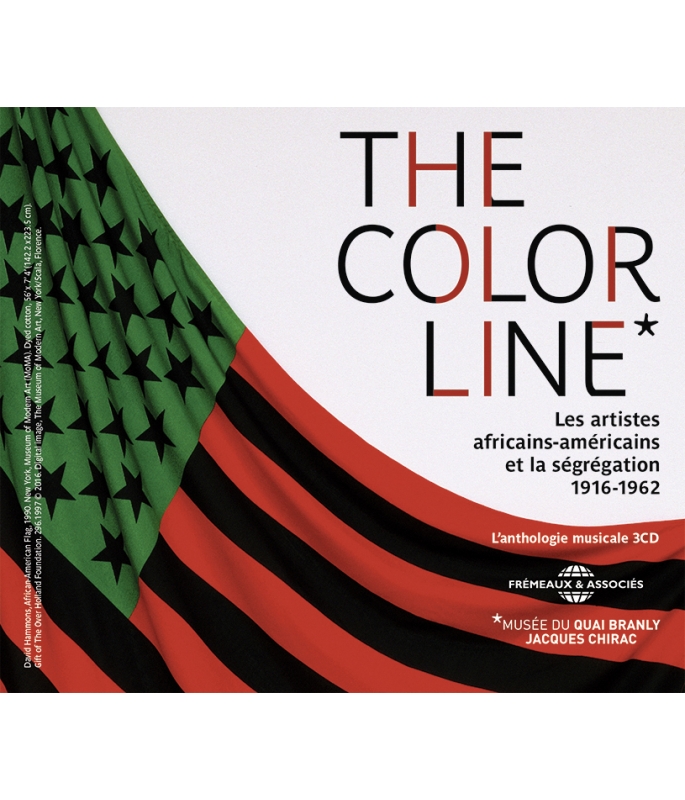

ANTHOLOGIE EXPOSITION MUSEE DU QUAI BRANLY DU 4 OCTOBRE 2016 AU 15 JANVIER 2017

Ref.: FA5654

Direction Artistique : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 3 heures 35 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

ANTHOLOGIE EXPOSITION MUSEE DU QUAI BRANLY DU 4 OCTOBRE 2016 AU 15 JANVIER 2017

COFFRET OFFICIEL DE L'EXPOSITION AU MUSEE DU QUAI BRANLY DU 4 OCTOBRE 2016 AU 15 JANVIER 2017

La ligne de couleur a longtemps dominé les relations humaines entre Noirs, Blancs et métis, et les domine encore souvent. Abolie en 1966 aux États-Unis, la ségrégation raciale a été largement évoquée dans les musiques afroaméricaines, inspirant des chefs-d’oeuvre de dignité, d’humour, de résistance et de spiritualité. Chants de travail, ménestrels au visage noirci, negro spirituals, calypso, jazz, blues, rock et gospel ont rythmé ces expressions d’une intense créativité. Bruno Blum raconte leurs histoires dans un livret de 24 pages, de la Harlem Renaissance au mouvement pour les Droits Civiques, dans ce coffret 59 titres musicaux publié en partenariat avec le musée du quai Branly Jacques Chirac à l’occasion de l’exposition The Color Line à Paris.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The color line has long dominated relations between Blacks, Whites and mixed race, and often still does. Abolished in 1966 in the USA, racial segregation was widely evoked in African-American musics, inspiring masterpieces of dignity, humour, resistance and spirituality. Work songs, blackface minstrels, negro spirituals, calypso, jazz, blues, rock and gospel gave a beat to these intensely creative expressions. In partnership with the Musée du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac, on the occasion of “The Color Line” exhibition in Paris, Bruno Blum tells the story of these 59 titles, from the Harlem Renaissance to the Civil-Rights movement, in a 24-page booklet. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : BRUNO BLUM

DROITS : GROUPE FREMEAUX COLOMBINI

EDITIONS : FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES / MUSEE DU QUAI BRANLY JACQUES CHIRAC

CD 1 - 1916-1948 : ROLL ON, HEAVE THAT COTTON - HARRY C. BROWNE • OH! SUSANNA - HARRY C. BROWNE • ETHIOPIA SHALL STRETCH FORTH HER HANDS ONTO GOD - MARCUS GARVEY • WE LOVE HUMANITY - MARCUS GARVEY • BLACK AND TAN FANTASY - DUKE ELLINGTON • DRY BONE SHUFFLE - ARTHUR “BLIND” BLAKE • THE AMERICAN WOMAN AND THE WEST INDIAN MAN PT. 1 - SAM MANNING • THE AMERICAN WOMAN AND THE WEST INDIAN MAN PT. 2 - SAM MANNING • HIGH SOCIETY - MONK HAZEL • CHICAGO HIGH LIFE - EARL HINES • MY MAMMY - AL JOLSON • W. P. A. BLUES - CASEY BILL WELDON • THE BOURGEOIS BLUES - LEAD BELLY • TARZAN OF HARLEM - CAB CALLOWAY • STRANGE FRUIT - BILLIE HOLIDAY • PARCHMAN FARM BLUES - BUKKA WHITE • TROUBLE - JOSH WHITE • UNCLE SAM SAYS - JOSH WHITE • OLD ALABAMA - B. B. E. • EARLY IN THE MORNING - 22.

CD 2 - 1944-1958 : JIM CROW - THE UNION BOYS • JIM CROW BLUES - LEAD BELLY • BLACK, BROWN AND BEIGE - DUKE ELLINGTON • WORK SONG • COME SUNDAY • THE BLUES • THREE DANCES • WATER BOY - PAUL ROBESON • PRISON BLUES - ALEX • HARD ROAD BLUES - FLOYD DIXON • BLACK, BROWN AND WHITE [GETBACK] - BIG BILL BROONZY (LIVE) • BROWN SKIN WOMEN - HOWLIN’ WOLF • LOW SOCIETY - RAY CHARLES • I’VE BEEN BORN AGAIN - THE BLIND BOYS OF ALABAMA • BLACK AND TAN FANTASY - THELONIOUS MONK • NO ROOM AT THE INN - MAHALIA JACKSON • THE ALABAMA BUS PTS 1 & 2 -BROTHER WILL HAIRSTON • JIM CROW TRAIN - JOSH WHITE • STAR-O - HARRY BELAFONTE • BROWN SKIN GIRL - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS • GOLD COAST - JOHN COLTRANE.

CD 3 - 1956 -1962 : BROWN EYED HANDSOME MAN - CHUCK BERRY • SAY BOSS MAN - BO DIDDLEY • NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN - LOUIS ARMSTRONG • THE GREAT GRANDFATHER - BO DIDDLEY • BETTER GIT IT IN YOUR SOUL - CHARLES MINGUS • KIYAKIYA [WHY DO YOU RUN AWAY?] - BABATUNDE OLATUNJI • CARRIE BELLE - JOHN DAVIS • WORKING MAN - BO DIDDLEY • ANCIENT AETHIOPIA - SUN RA • GEORGIA ON MY MIND - RAY CHARLES • DEATH DON’T HAVE NO MERCY - REVEREND GARY DAVIS • CHAIN GANG - SAM COOKE • WORK SONG - OSCAR BROWN, JR. • NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN - SNOOKS EAGLIN • ARE YOU SURE - ARETHA FRANKLIN • EXODUS - EDDIE HARRIS • MINSTREL AND QUEEN - THE IMPRESSIONS • YOU CAN’T JUDGE A BOOK (BY LOOKING AT THE COVER) - BO DIDDLEY • JUDGE HARSH BLUES - FURRY LEWIS • WE SHALL OVERCOME - GUY CARAWAN.

MUSIQUES ISSUES DE L’ESCLAVAGE AUX AMÉRIQUES...

HEP CATS, HIPSTERS & BEATNIKS 1936-1962 - EXPOSITION...

LES RACINES DES MUSIQUES NOIRES. EXPOSITION À LA CITÉ...

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Roll On Heave That CottonHarry Clinton BrowneWilliam Shakespeare Hay00:02:571916

-

2Oh! SusannaHarry Clinton BrowneStephen Foster00:03:361916

-

3Ethiopia Shall Stretch Forth Her Hands Onto GodMarcus GarveyMarcus Garvey00:03:031921

-

4We Love HumanityMarcus GarveyMarcus Garvey00:00:161922

-

5Black And Tan FantasyB.MileyDuke Ellington00:03:201927

-

6Dry Bone ShuffleDuke ElingtonBlind Blake00:02:391927

-

7The American Woman And The West Indian Man Pt. 1Sam ManningP. Grainger00:03:231928

-

8The American Woman And The West Indian Man Pt. 2Sam ManningP. Grainger00:02:561928

-

9High SocietyHazel MonkP. Steele00:03:021928

-

10Chicago High LifeEarl Hines00:02:521928

-

11My MammyAl JolsonSam M. Lewis00:03:121927

-

12W. P. A. BluesCasey Bill WeldonCasey Bill Weldon00:03:201936

-

13The Bourgeois BluesLead BellyLead Belly00:02:201939

-

14Tarzan Of HarlemCab CallowayNemo00:02:501939

-

15Strange FruitBillie HolidayAllan Lewis00:03:141939

-

16Parchman Farm BluesBukka WhiteBukka White00:02:401940

-

17TroubleJosh WhiteJosh White00:03:201940

-

18Uncle Sam SaysJosh WhiteJosh White00:02:431941

-

19Old AlabamaB.B.E.Traditionnel00:03:031948

-

20Early In The Morning22 and groupTraditionnel00:04:401948

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Jim CrowThe Union BoysLee Hays00:02:491944

-

2Jim Crow BluesLead BellyLead Belly00:02:251944

-

3Black Brown And Beige - Work SongDuke EllingtonDuke Ellington00:04:411944

-

4Come SundayDuke EllingtonDuke Ellington00:04:341944

-

5The BluesDuke EllingtonDuke Ellington00:04:381944

-

6Three DancesDuke EllingtonDuke Ellington00:04:301944

-

7Water BoyPaul RobesonAvery Robinson00:02:341945

-

8Prison BluesAlexInconnu00:02:261948

-

9Hard Road BluesDixon FloydFloyd Dixon00:03:171950

-

10Black, Brown And WhiteBig Bill BroonzyBig Bill Broonzy00:02:531952

-

11Brown Skin WomenHowlin' WolfChester Burnett00:02:461952

-

12Low SocietyRay CharlesRay Charles00:02:541953

-

13I Ve Been Born AgainThe Blind Boys of AlabamaJonnhy Fields00:02:551954

-

14Black And Tan FantasyThelonius MonkDuke Ellington00:03:261955

-

15No Room At The InnMahalia JacksonStoess00:04:191955

-

16The Alabama Bus Parts 1&2Brother Will HairstonBrother Will Hairston00:04:331956

-

17Jim Crow TrainJosh WhiteCuney Waring00:02:491956

-

18Star-OHarry BelafonteHarry Belafonte00:02:051955

-

19Brown Skin GirlLloyd Prince ThomasThomas Lloyd00:03:141957

-

20Gold CoastJohn ColtraneCurtis Fuller00:14:391958

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Brown Eyed Handsome ManChuck BerryChuck Berry00:02:181956

-

2Say Boss ManBo DiddleyBo Diddley00:02:321957

-

3Nobody Knows The Trouble I'Ve SeenLouis ArmstrongInconnu00:03:031958

-

4The Great GrandfatherBo DiddleyBo Diddley00:02:291958

-

5Better Git It In Your SoulCharles MingusCharles Mingus00:07:251959

-

6Kiyakiya (Why Do You Run Away) ?Babatunde OlatunjiBabatunde Olatunji00:04:161959

-

7Carrie BelleJohn DavisInconnu00:03:391959

-

8Working ManBo DiddleyBo Diddley00:02:331960

-

9Ancient AethiopiaSun RaSun Ra00:09:061959

-

10Georgia On My MindRay CharlesHoagy Carmichael00:03:361960

-

11Death Don'T Have No MercyReverend Gary DavisReverend Davis Gary00:04:421960

-

12Chain GangSam CookeSam Cooke00:02:351960

-

13Work SongOscar Brown JrOscar Brown Jr00:02:351960

-

14Nobody Knows The Trouble I'Ve SeenSnooks EaglinInconnu00:02:181961

-

15Are You SureAretha FranklinRobert Meredith Wilson00:02:441961

-

16ExodusEddie HarrisErnest Gold00:06:411961

-

17Minstrel And QueenThe ImpressionsCurtis Lee Mayfield00:02:221962

-

18You Can'T Judge A Book (By Looking At The Cover)Bo DiddleyBo Diddley00:03:151962

-

19Judge Harsh BluesFurry LewisLewis Furry00:05:321962

-

20We Shall OvercomeGuy CarawanGuy Carawan00:03:401960

The Color Line FA5654

L’anthologie musicale

The Color Line

Les artistes africains-américains

et la ségrégation

1916-1962

L’anthologie musicale par Bruno Blum

Les premiers enregistrements de musiciens afro-américains remontent aux années 1910 et les documents sonores accumulés depuis évoquent avec éloquence le martyr et l’émancipation des descendants d’esclaves. Ils permettent de retracer leur parcours tumultueux, restituant les voix, les styles musicaux, les émotions, opinions, joies et souffrances. Les Droits Civiques pour tous (accès au vote, à l’éducation, à tous les métiers, activités et lieux) n’ont été imposés qu’en 1966 par le président Lyndon Johnson au terme d’un siècle de luttes, à commencer par un accès de base à la culture, à l’histoire.

Blackface Minstrels

Basés sur un statut analogue à celui des animaux, les stéréotypes du racisme considéraient que les Afro-américains n’avaient pas « d’âme », qu’ils étaient fainéants, stupides et lubriques. Leur infériorité présumée servait de justification à leur exploitation, à leur oppression sans scrupules. Le racisme était profond, banal et certains n’hésitaient pas à en faire des chansons. Le théâtre vaudeville (variété de 1880 à 1930) utilisait des comédiens blancs au visage noirci au charbon, jouant des rôles de Noirs fainéants et ridicules. La future vedette du chant religieux chrétien Harry C. Browne, une des dernières grandes vedettes de cette période black face minstrels, enregistra aussi quantité de chansons dont Roll on, Heave that Cotton (composé en 1877). Browne y chante gaiement au son des bâteaux à aube du Mississippi, invectivant les niggers avec véhémence afin qu’ils chargent plus vite les balles de coton pour que son bateau gagne une course amicale avec un autre navire : Take it easy […] let that nigger take a slack a little

Dans sa version du célèbre Oh! Susanna (composé en 1848), qui faisait partie du répertoire de son spectacle black face minstrel, Browne chante l’insolite deuxième couplet d’origine (disparu depuis) où, en route vers sa bien-aimée, il tue cinq cents « niggers » au passage.

I jumped aboard the telegraph and traveled down the river,

Electric fluid magnified, and killed five hundred nigger

The bullgine bust, the horse ran off, I really thought I’d die

I shut my eyes to hold my breath — Susanna, don’t you cry.

Oh! Susanna, do not cry for me/I come from Alabama, with my banjo on my knee.

Le chanteur juif Al Jolson (My Mammy) était aussi une vedette black face minstrel, mais tenait des propos beaucoup plus mesurés où il rendait hommage au jazz. Il joua dans le tout premier long métrage parlant, The Jazz Singer (1927) où, au désespoir de son père cantor, un Juif quitte sa famille religieuse pour devenir chanteur de variété.

Des Noirs jouèrent aussi parfois des rôles de Noirs et perpétuaient — ou non — les stéréotypes racistes. Mais la société toute entière, Afro-américains compris, croyait aux aliénations de l’époque de l’esclavage, où l’homme blanc était le modèle, le but à atteindre, une cruelle ironie car ce but était par définition inaccessible aux Noirs. Et quel Afro-américain aurait bien pu vouloir leur ressembler ? Pourtant beaucoup essayaient.

Jim Crow

En 1865, l’abolition de l’esclavage a été imposée aux États-Unis par le président Abraham Lincoln au terme de la guerre de Sécession, un conflit majeur entre les états abolitionnistes du Nord et esclavagistes du Sud. Assassiné peu après, Lincoln n’a pu empêcher les lois « Jim Crow » qui ont progressivement entériné l’exclusion sociale et la séparation physique entre les Blancs dominateurs et les « Noirs ». « Une seule goutte » de sang africain (« one drop ») catégorisait une personne métis (« colored »). La vie des anciens esclaves, privés de nourriture, de logement, d’éducation, était souvent terrible, entre la peur et la misère décrites par Bo Diddley dans The Great Grandfather.

Ces lois scélérates ont perduré jusqu’en 1966 et sont dénoncées ici dans Jim Crow par les Union Boys, un groupe courageux réunissant Josh White (noir) et Pete Seeger (blanc) en 1944. Lead Belly y fit aussi allusion dans Jim Crow Blues la même année et Josh White en 1956 dans Jim Crow Train (des wagons étaient réservés aux Noirs et aux « colored » ).

Harlem Renaissance

La résistance s’organisa difficilement. Paru en 1901, le livre édifiant Up From Slavery de l’ancien esclave Booker T. Washington inspira les martyrs afro-américains en exigeant l’éducation pour tous. Puis W. E. B. Du Bois, un métis consensuel, premier doctorat « noir » sorti de Harvard, cofonda le NAACP en 1909 et devint un leader revendiquant des droits égaux pour tous. Du Bois n’était pas assez radical aux yeux de son adversaire le véhément nationaliste noir Marcus Garvey, un tribun jamaïcain catholique et panafricaniste installé à Harlem, d’où il galvanisa et unifia les Afro-américains entre 1919 et 1923 (il fut ensuite brisé et expulsé). Ses idées ont marqué la Harlem Renaissance (musique, littérature, etc.), le printemps culturel qui prit place dans le quartier noir de Harlem. À l’exemple de Moïse, il voulait instruire les Noirs puis les « ramener » en Afrique, alors appelée l’Éthiopie dans la Bible. Chrétienne depuis l’antiquité, l’Éthiopie inspirait les Afro-américains, notamment le mouvement Rastafari naissant en Jamaïque. En 1959 Sun Ra lui rendrait hommage avec Ancient Aethiopia. Citant la Bible en 1921 avec « Ethiopia Shall Stretch Forth her Hands Onto God », Garvey parlait ainsi :

« Les hommes noirs de Carthage, les hommes noirs d’Éthiopie, de Tombouctou, d’Alexandrie ont donné au monde quelque chose de proche de la civilisation. L’Éthiopie tendra ses mains vers Dieu, et des Princes viendront d’Égypte1. Ces classes, nations et races ont été bien silencieuses pendant les quatre derniers siècles… elles ont supporté la maltraitance, l’insulte, l’humiliation… leurs ancêtres ne peuvent être comparés qu’à Job qui lui aussi a relevé la tête et a crié à Dieu ‘Je suis un homme et j’exige le destin d’un homme, être traité comme un homme !’. Tant qu’à enseigner aux Noirs, je leur enseignerai de voir la beauté qui est en eux, d’arrêter d’éclaircir leur peau et d’essayer de ressembler à ceux qu’ils ne sont pas ! Du temps de l’esclavage, les mélanges raciaux et les croisements se sont produits car la femme noire n’avait pas de protection contre les esclavagistes. Il n’y a donc pas besoin pour les Noirs de continuer cette pratique qui rappelle tellement l’esclavage.

« Nos critiques diront que le problème racial sera résolu avec une éducation supérieure, une meilleure instruction, puis que les Noirs et les Blancs se réuniront. Mais ce jour n’arrivera pas tant que l’Afrique n’aura pas connu sa rédemption. Parce que si ceux qui, comme W. E. B. Du Bois, croient que le problème racial en Amérique sera résolu par de hautes études, ils marcheront entre le présent et l’éternité et ne verront jamais le problème résolu. Dieu a fait de l’homme le seigneur de sa création, il lui a donné possession et propriété du monde. Et vous avez été de fichus paresseux, au point que vous avez laissé d’autres s’approprier le monde entier, et maintenant ils vous font croire qu’il leur appartient et que vous n’y avez aucun droit ! Je n’ai pas à m’excuser d’être noir, car Dieu Tout Puissant savait exactement ce qu’il faisait quand il m’a fait noir !

« Si les Noirs connaissaient leur glorieux passé, ça les pousserait à se respecter. Vous avez entendu parler de Johnny Walker « Red » et « Black » ? Et bien, il a traversé des épreuves, mais il est toujours aussi fort ! Et bien, avec votre aide et à la grâce de Dieu, j’ai l’intention de continuer, car mon travail ne fait que commencer. Les générations futures auront entre leurs mains le guide par qui ils connaîtront les péchés du vingtième siècle. Je sais, et je sais que vous aussi croyez au pouvoir du temps et nous saurons attendre deux cents ans s’il le faut pour faire face à nos ennemis dans la postérité. Quand mes ennemis en auront assez… je reviendrai au cours de ma vie, ou dans la mort, pour vous servir comme je l’ai toujours fait. En

vie je serai le même, et une fois mort je serai la terreur des ennemis de la liberté des Africains ! »

Fracture sociale

Avec le New Deal du président Franklin D. Roosevelt, en 1933 le marché du travail fut ouvert aux Noirs par le Work Progress Administration (WPA), qui permit une intégration substantielle chantée par Casey Bill Weldon dans WPA Blues. Néanmoins, chantée par Josh White dans Uncle Sam Says, la color line permit rarement aux Noirs d’accéder à des responsabilités pendant la guerre, de posséder des armes ou de voler en avion.

Les métis jouissaient d’avantages évoqués par Big Bill Broonzy dans Black Brown and White. Ils étaient toutefois traités comme des êtres impurs, inférieurs, tout comme les Noirs. Certaines personnes à la peau très claire (« fair skin » ou « high yellow ») restaient entre elles. Mieux tolérées, elles n’avaient pas pour autant accès à la haute société blanche, la High Society bourgeoise qui donna son nom à un titre de Monk Hazel en 1928. En 1927 Duke Ellington fit de ce thème un de ses chefs-d’œuvre, Black and Tan Fantasy, repris magistralement par Thelonious Monk. Les Afro-américains rêvaient de liberté, de respect, de confort, de statut social élevé et de prestige. Dans Minstrel and Queen, Curtis Mayfield chante avec les Impressions l’histoire d’un ménestrel qui séduit une reine.

Le chanteur itinérant Lead Belly, un criminel et ancien bagnard révolté par sa condition misérable, chante dans Bourgeois Blues (1938) que les riches blancs « ne veulent pas de nègres ». Earl Hines, le premier pianiste de jazz moderne, fait lui aussi allusion à la fracture sociale avec son titre Chicago High Life de 1928. Idem pour Ray Charles, qui inversement enregistra Low Society pour évoquer le sous-prolétariat noir. C’est avec une attitude différente que le Tarzan of Harlem du hep cat excentrique Cab Calloway décrit un noir séduisant et attrayant, sans victimisation.

Le fossé était accentué par les familles nombreuses et les problèmes de logement chantés par Bo Diddley dans Say Boss Man. S’ajoutaient l’acculturation, l’ignorance, la zizanie et les origines géographiques. Les Noirs ruraux étaient souvent méprisés par les Noirs urbains, eux-mêmes divisés en fonction de leur couleur plus ou moins foncée évoquée par Howlin’ Wolf dans Brown Skin Women. La mentalité du statut social supérieur était héritée des esclaves de maison petit bourgeois, des favorisés alliés aux maîtres en échange d’avantages, et qui méprisaient souvent les esclaves des champs. Duke Ellington composa sur ce thème de la ligne de couleur, une suite à rapprocher de la musique classique, Black, Brown and Beige. Le comble de la ruralité était de venir des Antilles (West Indies), un stéréotype joué par le Trinidadien Sam Manning dans The American Woman and the West Indian Man : lors d’une querelle de rupture, un Jamaïcain noir menace d’envoûtement une femme américaine urbaine, à peau « jaune » plus claire. Les Caraïbes étaient considérées comme un terrain exotique où tous les plaisirs étaient permis. Après la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, les Américains blancs y allaient en vacances et rapportaient souvent des disques de musique locale (Cuba, Jamaïque, Îles Vierges américaines, Saint-Domingue2, etc.). Ils y mettaient parfois enceintes des femmes de pêcheurs, une situation cruelle décrite par Lloyd Prince Thomas, un chanteur des Îles Vierges américaines, dans Brown Skin Girl3. Cette chanson avait été rendue célèbre en 1956 par le Jamaïcain new-yorkais Harry Belafonte, qui interprétait aussi Star-O, un chant de dockers invoquant le soleil pour qu’il se lève, car leur nuit de travail s’achevait à l’aube4.

Chants de travail

Le travail des champs était dur (Bo Diddley dans Bo’s a Lumberjack) et avant-guerre nombre de familles ont émigré vers Detroit, Chicago ou New York. Les Afro-américains étaient particulièrement maltraités dans les états du sud, où ils vivaient majoritairement. Nomades, les musiciens avaient une vie solitaire difficile (Hard Road Blues de Floyd Dixon). Comme le chanta Billie Holiday dans l’emblématique Strange Fruit, à la moindre accusation les Afro-américains pouvaient être pendus avec ou sans procès par la populace blanche. La mort rodait aussi du fait de la misère, de la maladie (Death Don’t Have No Mercy de Reverend Gary Davis). Des innocents devenaient bagnards pour des peccadilles (Josh White dans Trouble, Bukka White dans Parchman Farm et Sam Cooke dans Chain Gang) ou de fausses accusations (Judge Harsh Blues, où Furry Lewis est condamné pour meurtre). Les anciennes plantations esclavagistes devenaient souvent des bagnes et l’esclavage continuait sans dire son nom. Les prisonniers jouaient de la musique avec des instruments de fortune (Prison Blues). Les chants de travail permettaient aux travailleurs forcés de projeter des images positives et de ne pas devenir fous. Ils sont évoqués par Duke Ellington dans Work Song, Oscar Brown, Jr. dans Work Song et le chanteur de comédies musicales Paul Robeson dans Water Boy (porteur d’eau qui distribuait à boire). Dans les documents Old Alabama et Early in the Morning, de vrais bagnards chantent au rythme du choc des outils, reproduits en studio par Bo Diddley pour son Working Man.

Negro Spirituals

Héritage de l’Afrique et de l’esclavage, ces chants de travail sont parfois devenus des invocations, des chants d’espoir et de rédemption appelés negro spirituals comme Carrie Bell, où le rythme au son des outils est simulé par la congrégation. Les spirituals étaient transmis oralement, plus tard affinés et déposés par des compositeurs. Souvent rejetés des temples anglicans (mais pas méthodistes) où le peuple blanc illettré pouvait se rapprocher des personnes cultivées, les Afro-américains ont créé leurs propres temples protestants (baptistes, pentecôtistes, méthodistes, quakers, etc.) au fil du 19e siècle. Les Afro-américains se sont instruits dans ces lieux où ils chantaient des spirituals. Ils voyaient dans les Juifs mythiques comme Moïse (Ol’ Man Mose) des évocations de leur propre histoire et rêvaient de paradis et/ou d’exode (Exodus d’Eddie Harris), de retour en Afrique. Dry Bone Shuffle de Blind Blake évoque les squelettes prenant miraculeusement vie dans le désert afin de donner la foi aux esclaves juifs marchant vers vers Babylone5. À partir des années 1930, des chansons gospel ont mis en forme le message de la Bible. Publiées en partitions, elles étaient diffusées un peu partout. La reine du gospel Mahalia Jackson chantait No Room at the Inn, où Jésus naît dans une étable car il n’y avait « pas de place » à l’auberge — une métaphore de la ségrégation raciale (les Noirs n’étaient pas acceptés dans les hôtels pour Blancs). Mahalia Jackson, le Golden Gate Quartet et les très rock Blind Boys of Alabama (I’ve Been Born Again) comptent parmi les plus grands interprètes des spirituals et du gospel. La future reine de la soul Aretha Franklin (Are You Sure) a commencé sa carrière en chantant le gospel avec son père pasteur. Les chansons gospel les plus populaires ont été arrangées de différentes façons. Ici Louis Armstrong reprend Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen dans un style jazzy tandis que Snooks Eaglin y apporte une couleur soul et rock.

Droits Civiques

Bien que musique de divertissement, le rock porta parfois des messages anti-discrimination, comme Chuck Berry avec Brown Eyed Handsome Man ou Bo Diddley dans You Can’t Judge a Book (by Looking at the Cover). En refusant de céder sa place dans un bus de l’Alabama où la ségrégation était en vigueur en 1955, Rosa Parks provoqua une grève des passagers noirs (évoquée par Brother Will Hairston dans The Alabama Bus) qui lança le mouvement pour les droits civiques que Martin Luther King mènerait à bien. Banni de Georgie après avoir refusé de chanter dans cet état ségrégationniste, Ray Charles chanta toute sa vie Georgia on my Mind, qui devint finalement l’hymne officiel de la Georgie en 1979.

Le jazzman Charles Mingus, une forte personnalité irascible, devint emblématique de la résistance dans le jazz des années 1960 avec des titres inspirés comme Better Git It In Your Soul.

La volonté de renouer avec l’Afrique se consolida dans les années 1950 lors des indépendances africaines. John Coltrane enregistra Gold Coast en hommage à la région d’où tant d’esclaves furent déportés. L’album à succès Drums of Passion du Yoruba nigerian américain Babatunde Olatunji, émigré à New York à l’âge de vingt-trois ans, contribua à l’affirmation d’une nouvelle image, enfin positive, de l’Afrique. Son Kiyakiya (« Pourquoi t’enfuis-tu en courant ? » ) fut adapté par Serge Gainsbourg, qui en fit son « Joanna ». L’hymne du mouvement des Droits Civiques, une vieille chanson devenue We Shall Overcome, a été rendu célèbre par Pete Seeger en 1963. Mais c’est un autre Blanc, Guy Carawan, qui en enregistra la première version définitive en 1961.

Bruno Blum, juillet 2016.

Merci à Giulia Bonacci, Jean Buzelin, Yves Calvez, Chris Carter, Christian Corre, Stéphane Colin, Bo Diddley, Bernard Lepesant, Nathalie Mercier, Philippe Michel, Pierre Mottais, Norbert Nobour, Gilles Pétard, Frédéric Saffar, Daniel Soutif, Christiane Taubira, Michel Tourte et Fabrice Uriac.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2016

1. Psaume 68:32.

2. Lire le livret et écouter Dominican Republic Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450) dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret et écouter Virgin Islands 1956-1960 (FA 5403) dans cette collection.

4. Lire le livret et écouter Harry Belafonte Calypso Mento Folk 1954-1957 (FA 5234) dans cette collection.

5. Ezéchiel 37.

Préface du coffret « Slavery in America »

par Christiane Taubira

L’expérience de l’invincibilité

Pourquoi cet esclavage-là ? Qu’a-t-il d’inépuisable ? Pourquoi se cabre-t-on contre la banalisation qui prétend que ‘l’esclavage a toujours existé’ ?

D’abord parce qu’aucun esclavage n’est banal, aucune servitude ordinaire, aucune oppression indolore. Ni par le passé, ni par nos temps, dans les mines, les usines, les ateliers, les caves, tout près de nous ou toujours près, car rien de la planète ne nous est inconnu.

Aussi parce que l’esclavage perpétré aux Amériques fut long, quatre siècles ; qu’il fut massif, près de quatre-vingt millions de personnes déportées d’Afrique à fond de cale1 ; qu’il fut précédé du génocide des Amérindiens ; qu’il fut racial et structura le racisme ; qu’il transforma les océans atlantique et indien en immenses cimetières humains ; qu’il est, sans précédent, intrinsèquement lié à la traite ; qu’il fut l’affaire d’États en pleine puissance économique ; qu’il s’adossa à des doctrines philosophiques, religieuses, scientifiques ; qu’il se légitima par le Droit, celui-ci fût-il perverti.

Parce qu’il bouleversa le monde par l’intrication des économies, l’émergence d’identités collectives, l’invention de langues, la fécondation syncrétique de religions, une créativité à la fois dense et effervescente.

Tout le temps que s’organisa ce qui fut, non un massacre, malgré les millions de morts ; non une extermination, malgré la dissolution des identités et filiations ; non un assassinat malgré les mutilations et exécutions, mais un crime, un crime contre l’humanité par l’expulsion méthodique et formelle de millions d’enfants, de femmes, d’hommes hors de la famille, de l’espèce, de la condition humaine ; pendant tout ce temps, du voyage dans les boyaux des navires négriers aux enchères sur les marchés de ces terres inconnues, du labeur harassant dans les plantations aux viols et sévices, au ravalement à l’état de ‘cheptel’, au statut de ‘meubles’, les captifs, réduits à l’esclavage, cernés de toutes parts par la collusion des intérêts économiques, politiques, cléricaux, font d’abord l’expérience de l’abandon transcendantal, de l’inanité eschatologique, celle du doute ontologique. Une vacillation qui aurait pu être fatale… Si n’était tapie, dans cette inexplicable et inextinguible pulsion de vie, l’incommensurable force résiliente de la prière, de la musique, de la poésie, d’une cosmogonie inventée pour échapper à cet univers apocalyptique. Étayés à leurs corps fourbus, fracassés, disloqués parfois, ceux qui ne rompirent pas par le marronnage ou l’Underground Railroad, celles qui, comme Sethe2, tuèrent leur petite fille par amour, celles dont les larmes s’étaient taries, ceux que l’impuissance à protéger femmes et enfants desséchait, chantèrent. Ils chantèrent pour réconcilier leurs corps exténués et meurtris avec leurs esprits désemparés mais endurants. Ils chantèrent en travaillant, en conspirant, en espérant. De leurs voix obstinées et d’instruments improbables, ils érigèrent la musique en art total. Inépuisable. Ils firent ainsi l’expérience de l’invincibilité.

Ce que nous sommes au monde en témoigne.

Christiane Taubira

Garde des Sceaux, ministre de la Justice

1. Selon Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau, Les Traites négrières (Paris, Gallimard, 2004), environ dix millions de captifs africains ont été déportés aux Amériques. Quatre-vingt millions serait le chiffre de la population d’esclaves évaluée avant l’abolition de 1865.

2. Toni Morrison, Beloved (Alfred Knopf, New York, 1987).

The Color Line

African-American Artists and Segregation – 1916-1962

They sang to reconcile their exhausted, wounded bodies and their distraught but enduring spirits. They sang as they worked, conspired, hoped. Out of their persistent voices and unlikely instruments they erected music as total art. Inexhaustible. Thus they had the experience of invincibility.

What we are to the world bears witness of it.

— Christiane Taubira, French Minister of Justice and Lord Chancellor1

The Musical Anthology by Bruno Blum

The first African-American music recordings appea-red in the 1910s and the audio documents that have accumulated since eloquently evoke the martyrdom and emancipation of the descendants of slaves. They make it possible to trace back their eventful route, rendering the voices, musical styles, emotions, opinions, joys and sufferings. Civil Rights for all (access to the vote, education, all jobs, all human activities and places) were belatedly imposed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1966, after a century of struggles, starting with basic access to culture and history.

Blackface Minstrels

Based on a status analogous to that of animals, racist stereotypes suggested that African-Americans had no “soul,” that they were lazy, stupid and lustful. Their presumed inferiority was used to justify exploitation and unscrupulous oppression. Racism was deeply embedded, and common. Vaudeville theater (variety shows 1880-1930) used white actors with their face coloured with charcoal to play the part of lazy, ridiculed Blacks. Some were so bold as to make songs out of it. The Christian, religious song star-to-be Harry C. Browne was one of the last big names of the blackface minstrel era. He also recorded many songs including Roll On, Heave That Cotton (which was composed in 1877). Browne is gaily singing to the sound of the Mississippi steamboats, vehemently cursing niggers, hoping to hurry their loading of his ship in order to win an amicable race with another boat: Take it easy […] let that nigger take a slack a little

In his version of the famous Oh! Susanna (composed in 1848), which was part of his blackface minstrel show, Browne is actually singing the quirky, original second verse (now vanished) where the narrator casually kills “five hundred niggers” on his way to his ladylove.

I jumped aboard the telegraph and traveled down the river,

Electric fluid magnified, and killed five hundred nigger

The bullgine bust, the horse ran off, I really thought I’d die

I shut my eyes to hold my breath — Susanna, don’t you cry.

Oh! Susanna, do not cry for me/I come from Alabama, with my banjo on my knee.

Jewish singer Al Jolson (My Mammy) was also a blackface minstrel, but he sang moderate lyrics and paid tribute to jazz: in the first ever feature-length motion picture with synchronized dialogue and song sequences, The Jazz Singer (1927), a “talkie” where, to his father’s utter despair, a Jew left his religious family to become a pop singer. Sometimes Black actors also played Black people’s parts and perpetuated — or not — racist stereotypes. But the entire society, African Ame-ricans included, believed in the alienation of the slavery days, when the White man was the mark to hit, the model — a cruel irony, as this goal was, by definition, impossible to reach by anyone who was black. And which African-American would have wanted to be like them? Well, many tried.

Jim Crow

In 1865, the abolition of slavery was imposed by Abraham Lincoln in the United States, following a civil war between the Northern abolitionist states and the Southern states, which supported slavery. Murdered soon after, Lincoln could not stop the “Jim Crow” laws that, little by little, ratified social exclusion and physical separation between dominant Whites and “Blacks.” “One drop” of African blood categorized a person as “colored.”

The lives of former slaves, who were deprived of food, housing and education, were often terrible, midway between fear and misery, as described by Bo Diddley in The Great Grandfather. Those appalling laws lasted until 1966. They are condemned here in Jim Crow by the Union Boys, a brave group uniting Josh White (black) and Pete Seeger (white) in 1944. That same year, Lead Belly also alluded to them in Jim Crow Blues. So did Josh White in Jim Crow Train: some train carriages were marked “Whites only.”

Harlem Renaissance

Resistance was difficult to organise. Former slave Booker T. Washington’s edifying book Up From Slavery was published in 1901. Washing-ton demanded education for all and inspired the African-American martyrs. Then W. E. B. Du Bois, a consensual, mixed-race African-American who gained the first ‘colored’ Ph.D to come out of Harvard, co-founded the NAACP in 1909 and became a leader demanding equal rights for all.

Du Bois was not radical enough according to his opponent, Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican, Roman Catholic tribune and a vehement Black nationalist who had settled in Harlem. Garvey galvanised and united African-Americans between 1919 and 1923 (he was then broken and expelled). His ideas marked the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural springtime in the black neighbourhood of Harlem (music, literature, etc.).

Following the pattern of Moses, he wanted to educate Black people and bring them “back” to Africa, then called Ethiopia in the Bible. Ethiopia had been a Christian country since antiquity and it inspired African-Americans, soon including the Rastafari movement in Jamaica.

In 1959, Sun Ra paid tribute to it with Ancient Aethiopia. Quoting the Bible in 1921, thus spoke Garvey:

“Black men at Carthage, Black men of Ethiopia, of Timbuktu, of Alexandria, gave the likes of civilization to this world. Ethiopia shall stretch forth her hands unto God, and Princes shall come out of Egypt2. Those classes, nations, races, have been quite quiet for over four centuries… who have merely borne abuse, insult, humiliation… whose forbearance can only be compared to the prophet Job, who likewise lifted his bowed head and raised it up to God and cried out, ‘I am a man and demand a man’s chance, and a man’s treatment in this world!’

“As I shall teach the Black man… I shall teach the Black man to see beauty in his own kind and stop bleaching his skin and otherwise looking like what he’s not! Back in the days of slavery, race mixture and race miscegenation had occured because the African woman had no protection from the slavemaster. Therefore there is no need today for Black people to themselves freely continue a practice that smacks so much of slavery.

“Our critics say that the race problem will be solved through higher education, through better education, and then Black and White will come together. That day will never happen until Africa is redeemed. Because if those who, like W. E. B. Du Bois, believe that the race problem will be solved in America through higher education, they will walk between now and eternity and never see the problem solved.”

“God made man lord of his creation, gave him possession and ownership of the world. And you have been so darned lazy, that you’ve allowed the other fellow to run away with the whole world, and now he’s bluffing you and telling you that the world belongs to him and that you have no part in it! I don’t have to apologise to anybody for being Black, because God Almighty knew exactly what he was doing when he made me Black!

“If Black people knew their glorious past, then they would be more inclined to respect themselves. Yes, you’ve heard of Johnny Walker ‘Red,’ and ‘Black’? Well, he had his adversities, but he’s still going strong! Well, I intend, with your help and God’s grace, to continue, because my work has only just begun. And future generations shall have in their hands the guide by which they shall know the sins of the 20th century. I know, and I know you too believe in time, where we shall wait patiently for 200 years if need be, to face our enemies through our posterity. When my enemies are satisfied… In life I shall come back, or in death, even, to serve you as I served before. In life I shall be the same, in death I shall be a terror to the foes of African liberty!”

Social fracture

With President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, by 1933 the labor market welcomed African-Americans, through the Work Progress Administration (WPA) program, which allowed substantial integration and which was sung about by Casey Bill Weldon in WPA Blues. However, the color line remained, and it often denied Black people access to responsibilities during the Second World War, such as handling guns or flying, as recounted by Josh White in Uncle Sam Says.

According to Big Bill Broonzy in Black Brown and White, mixed race people enjoyed some advantages. However, they were still treated as impure, inferior people, just as Blacks were. Some truly light-skinned people (“fair skin,” “high yellow”) stayed amongst themselves. Although better tolerated, they did not have access to the white High Society, which gave its name to a Monk Hazel tune in 1928. In 1927, Duke Ellington recorded Black and Tan Fantasy on this theme, one of his masterpieces, later covered by Thelonious Monk.

African-Americans dreamt of freedom, respect, comfort, high social status and prestige. In Minstrel and Queen, Curtis Mayfield leads The Impressions, singing the story of a minstrel seducing a queen.

Wandering singer Lead Belly was a criminal, a former convict revolting against his miserable condition. In Bourgeois Blues (1938) he sang that rich white people “don’t want no niggers around.” Earl Hines, the first modern jazz pianist, is also alluding to the social fracture with his 1928 tune, Chicago High Life. Inversely, with Low Society, Ray Charles expresses his feelings about the black underclass. Displaying a different stance, eccentric hep cat Cab Calloway’s Tarzan of Harlem describes a seducive, attractive Black man, never giving in to victimisation.

Large families and housing problems made the gap worse, as suggested by Bo Diddley in Say Boss Man. Acculturation, ignorance, discord and geographic origins added to the problem. Rural Blacks were often scorned by urban ones, who were themselves disunited through their colour differences, as sung by Howlin’ Wolf in Brown Skin Women. The superior social status mentality was a legacy of “house slaves,” who enjoyed privileges and were allied to their masters, in exchange for advantages — and who often scorned field slaves.

Duke Ellington composed Black, Brown and Beige about the color line, a musical suite attempting an analogous form to that of classical music suites. The limit in rural, “country” status was to be from the Caribbean, a stereotype shown by the character played by Trinidadian Sam Manning in The American Woman and the West Indian Man: during a break-up quarrel, a Black Jamaican threatens an American, “yellow,” light-skinned, urban woman about putting a spell on her.

The Caribbean islands were then an exotic playground where all earthly pleasures were allowed. After World War II, White Americans would spend holidays there, bringing back local music records as souvenirs (Cuba, Jamaica, U.S. Virgin Islands, Dominican Republic3, etc.).

Sometimes they also got fishermen’s wives pregnant, a cruel situation described by U. S. Virgin Islands singer Lloyd Prince Thomas in Brown Skin Girl4. This song had been made famous by Harry Belafonte, who also sung Star-O, a dockers’ work song calling upon the sun to rise, as the night shift ended at dawn.

Work Songs

Field work was hard (Bo Diddley in Bo’s a Lum-berjack) and before WWII many families emigrated to Detroit, Chicago or New York. Nomadic musicians had a tough, solitary life (Hard Road Blues by Floyd Dixon). As Billie Holiday sang in the emblematic Strange Fruit, at the slightest accusation African-Americans could be hanged by the local populace with or without trial. Death was also roaming because of misery and illness (Death Don’t Have No Mercy by Reverend Gary Davis). Innocents became convicts for peccadillos (Josh White in Trouble, Bukka White in Parchman Farm and Sam Cooke in Chain Gang) or false accusations (Furry Lewis in Judge Harsh Blues). What was once a slave plantation often became a penitentiary and slavery kept going under a different name. Prisoners played music with makeshift instruments (Prison Blues).

Work songs allowed forced laborers to project positive pictures in their minds and not go insane. They are alluded to by Duke Ellington in Work Song and Broadway musicals singer Paul Robeson in Water Boy (who despatched drinking water in the fields). In documents like Old Alabama and Early in the Morning, real convicts sing to the rhythm of tools hitting the soil, which were recreated in the studio by Bo Diddley for his Working Man.

Negro Spirituals

A legacy from Africa and slavery, these work songs sometimes became invocations, hope and redemption songs called negro spirituals, such as Carrie Bell, where the sound of tools is simulated by the congregation. Spirituals were transmitted orally, then often polished and registered by various composers.

African-Americans were mostly rejected from Anglican churches (except for the Methodist ones) where illiterate Whites could mix with educated people. So they created their own churches (Baptist, Pentecostal, Methodist, etc.) throughout the 19th century. They got educated in those same churches, where they also sang spirituals. In mythical Jews such as Moses, they saw evocations of their own history and prayed for access to paradise and/or exodus (Exodus by Eddie Harris) — the journey “back to Africa”.

Blind Blake’s Dry Bone Shuffle is about skeletons miraculously coming alive in the desert, in order to give faith to Jewish slaves walking their way to Babylon5. From the 1930s onwards, gospel songs put the Bible’s messages together in songs. They were published on scores and distributed widely. The queen of gospel, Mahalia Jackson, sang No Room at the Inn, in which Jesus is born in a stable because there was “no room” at the inn — an obvious metaphor for racial segregation (Blacks were not allowed in hotels for Whites).

Mahalia Jackson, the Golden Gate Quartet and the rocking Blind Boys of Alabama (I’ve Been Born Again) rank amongst the greatest gospel artists. The ‘queen of soul-to-be,’ Aretha Franklin, (here on Are You Sure) started her career singing gospel alongside her Reverend father. The most popular gospel songs were arranged in many different ways. Here Louis Armstrong covers Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen in a jazzy style, whereas Snooks Eaglin brings a soulful, rock edge to it.

Civil Rights

Although it was meant for entertainment, rock music sometimes conveyed messages protesting against racial discrimination, as Chuck Berry did with Brown Eyed Handsome Man and Bo Diddley with You Can’t Judge a Book (by Looking at the Cover). In refusing to give up her seat to a White man in a segregated Alabama bus in 1955, Rosa Parks started an African-American passenger strike (sung about by Brother Will Hairston in The Alabama Bus) that launched the Civil Rights movement. This was the great movement that Martin Luther King would later have so much influence upon. Banned from Georgia after he refused to sing in this segregationist state, for the rest of his life Ray Charles sang Georgia on my Mind, which eventually became the Georgia State official hymn in 1979. Jazzman Charles Mingus, a short-tem-pered, strong personality became an emblem of resistance to racism in 1960s jazz with inspired tunes like Better Git It In Your Soul.

The will to re-establish a link with African roots streng-thened in the 1950s as several African countries obtained their independence. John Coltrane recorded Gold Coast as a tribute to a land from which so many slaves had been deported. The successful Drums of Passion album by Nigerian-American Yoruba Babatunde Olatunji contributed to giving a new, positive image to Africa at long last. His song Kiyakiya (“Why Do You Run Away?”) was adapted by Serge Gainsbourg, who turned it into his “Joanna”.

The Civil Rights hymn turned out to be an old folk song that became We Shall Overcome, made famous by Pete Seeger in 1963. But it was another White man, Guy Carawan, who recorded its first definitive version in 1961.

Bruno Blum, July 2016.

Thanks to Giulia Bonacci, Jean Buzelin, Yves Calvez, Chris Carter, Christian Corre, Stéphane Colin, Bo Diddley, Bernard Lepesant, Nathalie Mercier, Philippe Michel, Pierre Mottais, Norbert Nobour, Gilles Pétard, Frédéric Saffar, Daniel Soutif, Christiane Taubira, Michel Tourte et Fabrice Uriac6.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2016

1. Excerpt from Christiane Taubira’s preface to Bruno Blum’s Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 (FA 5467) booklet in this series.

2. Psalm 68:32.

3. Cf. Dominican Republic Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450) in this series.

4. Cf. Virgin Islands 1956-1960 (FA 5403) in this series.

5. Ezechiel 37.

Discography

Future generations shall have in their hands the guide

by which they shall know the sins of the 20th century.

— Marcus Garvey, 1921.

Disc 1 - 1916-1948

1. ROLL ON, HEAVE THAT COTTON - Harry C. Browne

(William Shakespeare Hay)

Harry Clinton Browne-v, bj; orchestra. Columbia COL A-2015, mx 46643. New York City, March 1916.

2. OH! SUSANNA - Harry C. Browne with the Peerless Quartet

(Stephen Foster)

Harry Clinton Browne-v, bj; The Peerless Quartet: John H. Meyer, Harry Haley McClaskey as Henry Burr (leader), Frank Croxton, Albert Campbell-v; with orchestra. Columbia A-2218, mx 46873. New York, June 1916.

3. ETHIOPIA SHALL STRETCH FORTH HER HANDS ONTO GOD - Marcus Garvey

(Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jr. aka Marcus Garvey)

Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jr. as Marcus Garvey-v; audience. Live recording, possibly New York City, circa July, 1921.

4. WE LOVE HUMANITY - Marcus Garvey

(Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jr. aka Marcus Garvey )

Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jr. as Marcus Garvey-v. From “Explanation of the Objects of the Universal Negro Improvement Association.” See Bee Record 208. New York City, 1922.

5. BLACK AND TAN FANTASY - The Washingtonians

(Edward Kennedy Ellington aka Duke Ellington, James Wesley Miley aka Bubber Miley)

James Wesley Miley as Bubber Miley-muted tp; Louis Metcalf-tp; Joe Nanton as Tricky Sam-tb; Otto Hardwick-sa, as, bs; Prince Robinson (and another?)-cl, ts; Edward Kennedy Ellington as Duke Ellington-p, dir.; Fred Guy-banjo; Henry Edwards-bb; Sonny Greer-d. New York, April 7, 1927.

6. DRY BONE SHUFFLE - Arthur “Blind” Blake

(Arthur Blake aka Blind Blake)

Arthur Blake as Blind Blake-v, g; unknown-rattlebones. Paramount 4462. Chicago, April 13 or 14, 1927.

7. THE AMERICAN WOMAN AND THE WEST INDIAN MAN Pt. 1 - Sam Manning & Anna Freeman

(Porter Grainger)

Sam Manning, Anna Freeman-v; Porter Grainger-p. Brunswick 7028. New York City, March 19, 1928.

8. THE AMERICAN WOMAN AND THE WEST INDIAN MAN Pt. 2 - Sam Manning & Anna Freeman

(Porter Grainger)

Same as above.

9. HIGH SOCIETY - Monk Hazel and his Bienville Roof Orchestra

(Porter Steele)

Sharkey Bonano-tp; Luther Lamar-tuba; Hal Jordy-as, bs; Sidney Arodin-cl; Freddy Newman-p; Joe Capraro-g; Arthur Hazel as Monk Hazel-d. Brunswick 4181. New Orleans, December, 1928

10. CHICAGO HIGH LIFE - Earl Hines

(Earl Kenneth Hines)

Earl Kenneth Hines as Earl Hines-piano. QRS R-7037. Long Island City, New York, December 8, 1928.

11. MY MAMMY - Al Jolson

(Walter Donaldson, Sam M. Levine aka Sam M. Lewis, Joe Young)

Asa Yoelson as Al Jolson-v; Abe Lyman & his California Orchestra. Recorded by George Robert Groves. From the 1927 film The Jazz Singer. Hollywood, circa Spring, 1927.

12. W. P. A. BLUES - Casey Bill Weldon

(William Weldon aka Casey Bill Weldon)

Casey Bill Weldon-v, g; Black Bob-p; Bill Settles-b. Chicago, February 12, 1936.

13. THE BOURGEOIS BLUES - Lead Belly

(Huddie Leadbetter aka Lead Belly, Alan Lomax)

Huddie Leadbetter as Lead Belly-v, g. New York City, April 1, 1939.

14. TARZAN OF HARLEM - Cab Calloway

(Henry Nemo, Irving Mills, Lupin Fien)

Cabell Calloway as Cab Calloway-v, dir; Mario Bauza, John Birks as Dizzy Gillespie, Lammar Wright, Doc Cheatham-tp; Keg Johnson, Claude Jones, De Priest Wheeler-tb; Chauncey Haughton, Andrew Brown-cl, as; Walter Thomas, Chu Berry-ts; Bennie Payne-p; Danny Barker-g; Milton Hinton-sb; Cozy Cole-d; Edgar Battle-a. Vocalion 5267. New York, October 17, 1939.

15. STRANGE FRUIT - Billie Holiday and her Orchestra

(Abel Meeropol aka Lewis Allan)

Eleanora Fagan as Billie Holiday-v; Frankie Newton-tp; Tab Smith-as; Stanley Payne, Kenneth Hollon-ts; Sonny White-p; McLin-g; John

Williams-b; Eddie Dougherty-d. Commodore WP-24403-B. New York, April 20, 1939.

16. PARCHMAN FARM BLUES - Bukka White

(Booker T. Washington White aka Bukka White)

Booker T. Washington White as Bukka White-v, slide metal acoustic g; Robert Brown as Washboard Sam-washboard. Chicago, March 7, 1940.

17. TROUBLE - Josh White

(Joshua Daniel White)

Joshua Daniel White as Josh White-v, g; Sam Gary-v; Bill White-v, b. New York City, June 4, 1940.

18. UNCLE SAM SAYS - Josh White

(William Waring Cuney, Joshua Daniel White)

Joshua Daniel White as Josh White-v, g. New York City, 1941.

19. Old Alabama - B.B. and group

(traditional)

“B.B.” and six prisoners chopping firewood-v. Tradition TLP-1020. Recorded by Alan Lomax, Mississippi State Penitentiary (aka Parchman Farm), 590 Parchman 40 Rd, Parchman, Mississippi 38738, 1947 or 1948.

20. Early in the Mornin’ - 22 and group

(traditional)

“22,” “Little Red,” “Tangle Eye,” “Hard Hair”-v, double cutting axes. Tradition TLP-1020. Recorded by Alan Lomax, Mississippi State Penitentiary (aka Parchman Farm), 590 Parchman 40 Rd, Parchman, Mississippi 38738, 1947 or 1948.

Disc 2 - 1944-1958

1. JIM CROW - The Union Boys

(Lee Hays, Peter Seeger aka Pete Seeger)

Josh White-v, g; Peter Seeger aka Pete Seeger-v; Burl Ives-v; Alan Lomax-v; Tom Glazer-v; Sonny Terry-v; Brownie McGhee-v. Possibly New York City, March, 1944.

2. JIM CROW BLUES - Lead Belly

(Huddie Ledbetter aka Lead Belly)

Huddie Ledbetter as Lead Belly-v, g; New York City, May 1944.

BLACK, BROWN AND BEIGE - Duke Ellington

(Edward Kennedy Ellington aka Duke Ellington)

Shelton Hemphill, James Jordan as Taft, William Anderson as Cat, Ray Nance-tp; Joe Nanton as Tricky Sam, Claude Jones, Lawrence Brown-tb; Johnny Hodges, Otto Hardwick-as; Al Sears-ts; Jimmy Hamilton-ts, cl; Harry Carney-bs; Edward Kennedy Ellington as Duke Ellington-p; Fred Guy-g; Alvin Raglin as Junior-b; William Greer as Sonny-d.

3. a) WORK SONG

4. b) COME SUNDAY

Johnny Hodges, as. New York, December 11, 1944.

5. c) THE BLUES

Joya Sherrill-v. New York, December 12, 1944.

6. d) THREE DANCES

New York, December 12, 1944.

7. WATER BOY - Paul Robeson

(Avery Robinson)

Paul Robeson-v; Lawrence Brown-p. Possibly New York City, December 28, 1945.

8. PRISON BLUES - Alex

Recorded by Alan Lomax, Mississippi State Penitentiary (aka Parchman Farm), 590 Parchman 40 Rd, Parchman, Mississippi 38738, 1947 or 1948.

9. HARD ROAD BLUES (Travelin’ On) - Floyd Dixon with Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers

(Jay Riggins, Jr. aka Floyd Dixon)

Jay Riggins, Jr. as Floyd Dixon-v, p; Maxwell Davis-ts; Johnny Moore, Oscar Moore-g; Johnny Miller-b; Ellis Walsh-d. Capitol CDP 36293. Los Angeles, September 19, 1950.

10. BLACK, BROWN AND WHITE [aka Get Back] - Big Bill Broonzy

(Lee Conley Bradley aka Big Bill Broonzy)

Lee Conley Bradley as Big Bill Broonzy-v, g. Salle Pleyel, Paris, France, February 7, 1952.

11. BROWN SKIN WOMEN - Howlin’ Wolf

(Chester Burnett as Howlin’ Wolf)

Chester Burnett as Howlin’ Wolf-v, harmonica; Ike Turner-p; Willie Johnson-g; b; Willie Steel-d. West Memphis, Arkansas, February 12, 1952.

12. LOW SOCIETY - Ray Charles

(Ray Charles Robinson aka Ray Charles)

Ray Charles Robinson as Ray Charles-p. Atlantic 81694. New York, May 10, 1953.

13. I’VE BEEN BORN AGAIN - The Blind Boys of Alabama

(Johnny Fields)

Clarence Fountain-lead v; Rev. Samuel K. Lewis-lead v; George Scott-tenor v; Olice Thomas-Baritone v; Johnny Fields-bass v; g, b, d. Produced by Arthur Goldberg as Art Rupe. 1954.

14. BLACK AND TAN FANTASY - Thelonious Monk

(Edward Kennedy Ellington as Duke Ellington, James Wesley Miley as Bubber Miley)

Thelonious Sphere Monk-p; Oscar Pettiford-b; Kenny Clarke-d. New York City, July 21 or 27, 1955.

15. NO ROOM AT THE INN - Mahalia Jackson

(Erwin Stoess, Mel Sterett)

Mahalia Jackson-v; Mildred Falls-p; Ralph Jones-org; possibly Milton Hilton-b; Lionel Hampton-vibes. New York City, June 2, 1955.

16. THE ALABAMA BUS Parts 1 & 2 - Brother Will Hairston

(Will Hairston)

Will Hairston-v; p; Washboard Willie-washboard. Detroit, circa 1956.

17. JIM CROW TRAIN - Josh White

(William Waring Cuney)

Joshua Daniel White as Josh White-v, g; Al Hall-b; Sonny Greer-d. New York City, April 1, 1956.

18. STAR-O - Harry Belafonte

(Harry Belafonte, Irving Burgie aka Lord Burgess, Wiliam Attaway, arranged by Tony Scott. Adapted from the Jamaican traditional “Day Dah Light”)

Harry Belafonte-lead v; Herbert Levy, flute; Milton Hinton, bass; Alexander Cambrelen, congas; Mario Castillo, conga; Ossie Johnson, drums; Irving Burgie as Lord Burgess, Charles Colman, J. Hamilton Grandison, Joseph Lewis, Broc Peters, Sherman Sneed, Herbert Stubbs, John White and Gloria Wynder-vocal chorus ; Tony Scott, leader. Produced by Herman Diaz Jr., recorded at Webster Hall, New York City, October 20, 1955.

Note: the original Jamaican version “ Day Dah Light “ is available on Jamaica-Mento 1951-1958 (FA5275) in this series.

19. BROWN SKIN GIRL - Lloyd Prince Thomas and the Calypso Troubadours

(Lloyd Thomas)

Lloyd Thomas as Lloyd Prince Thomas-v; backed by The Calypso Troubadours: p, b, bongos, congas, maracas, vocal chorus. Que Records, possibly New York, circa 1957.

20. GOLD COAST - John Coltrane & Wilbur Harden

(Curtis Fuller)

Wilbur Harden-tp; John Coltrane-ts; Tommy Flanagan-p; Al Jackson-b; Art Taylor-d. Recorded by Rudy Van Gelder. Hackensack, New Jersey, June 24, 1958.

Disc 3 - 1956-1962

1. BROWN EYED HANDSOME MAN - Chuck Berry

(Charles Edward Anderson Berry aka Chuck Berry)

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below-d. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, April 16, 1956.

2. SAY BOSS MAN - Bo Diddley

(Ellas Bates McDaniel aka Bo Diddley)

Ellas Bates McDaniel as Bo Diddley-v, g; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g; Lafayette Leake-p; Clifton James or Frank Kirkland-d; Jerome Green-maracas; Probably The Moonglows (overdub): Harvey Fuqua, Bobby Lester, Prentiss Barnes, Alexander Graves aka Pete-v. Chess Studio, August 15, 1957.

3. NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN - Louis Armstrong with Sy Oliver’s Choir and Orchestra

(unknown, arranged by Sy Oliver)

Louis Armstrong-v, tp; Trummy Young-tb; Dave McRae-cl; Nickie Tragg-org; Billy Kyle-p; George Barnes-g; Mort Herbert-b; Barrett Deems-d; Ten singer Choir; Sy Oliver-arr., cond. New York City, February 4, 1958.

4. THE GREAT GRANDFATHER - Bo Diddley

(Ellas Bates McDaniel aka Bo Diddley)

Ellas Bates McDaniel as Bo Diddley-v, g; Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon-b; Clifton James or Frank Kirkland-d. Probably Bell Sound Studios, New York City, late 1958.

5. BETTER GIT IT IN YOUR SOUL - Charles Mingus

(Charles Mingus, Jr.)

William Dennis, James Knepper-tb; John Handy III, Booker T. Ervin, Jr., Shafi Hadi- saxophones; Horace L. Parlan-p; Charles Mingus-b; Dannie Richmond-d. Columbia 30th Street Studio, New York City, May 5 or 12, 1959.

6. KIYAKIYA [Why Do You Run Away?] - Babatunde Olatunji

(adapted by Babatunde Olatunji)

Michael Babatunde Olatunji-hand drums; Baba Hawthorne Bey, Roger Sanders as Montego Joe, Taiwo Duval-percussion. Afuavi Derby, Akwasiba Derby, Barbara Gordon, Dolores Oyinka Parker, Helen Haynes, Helena Walker, Ida Beebee Capps, Louise Young, Ruby Wuraola Pryor-vocal chorus. Columbia CS 8210. New York City, July 8, 1959.

7. Carrie Belle - John Davis and the Spiritual Singers of Georgia

(unknown)

John Davis-lead v; Jerome Davis, Peter Davis, Bessie Jones, Joe Armstrong, Henry Morrison, Willis Proctor, Ben Ramsay-v. Prestige/International 25001. Recorded by Alan Lomax in Frederica, St. Simons Island, Georgia, assisted by Shirley Collins, October 12 or 13, 1959.

8. WORKING MAN - Bo Diddley

(Ellas Bates McDaniel aka Bo Diddley)

Ellas Bates McDaniel as Bo Diddley-g,v; Lafayette Leake or Billy Stewart-p; Jesse James Johnson-b (not used); Willie Dixon-overdubbed b; Billy Downing-d; Jerome Green, maracas; Ellas Bates McDaniel as Bo Diddley, Peggy Jones as Lady Bo and others-vocal group. Bo Diddley’s home studio, Washington D.C., February 1960.

9. ANCIENT AETHIOPIA - Sun Ra

(Le Sony’r Ra aka Sun Ra, born Herman Poole Blount)

Hobart Dotson-tp; James Spaul-ding, Marshall Allen-as, fl; John Gilmore-ts; Charles Davis-bs; Pat Patrick-bs, fl; Sun Ra-piano; Ronnie Boykins-b; William Cochran-d. Produced by Alton Abraham. Saturn K7 OP3590. Chicago, March 6, 1959.

10. GEORGIA ON MY MIND - Ray Charles

(Hoagland Howard Carmichael aka Hoagy Carmichael, Stuart Graham Steven Gorrell)

Ray Charles Robinson as Ray Charles-v, p; Edgar Willis-b; Milton Turner-d; with 15 strings; The Jack Halloran Singers-vocal chorus; Hank Crawford, conductor; Ralph Burns, arr. New York City, March 25, 1960.

11. DEATH DON’T HAVE NO MERCY - Reverend Gary Davis

(Gary Davis)

Gary Davis as Reverend Gary Davis-v, g. Prestige 7805. Produced by Kenneth S. Goldstein. Recorded by Rudy Van Gelder. Hackensack, New Jersey, August 24, 1960.

12. CHAIN GANG - Sam Cooke

(Samuel Cook aka Sam Cooke, Charles Cooke)

Samuel Cook as Sam Cooke-v; Cliff White-g; Hugo Perretti-org; Hank Jones-p; orchestra conducted by Glenn Osser; unknown b, d, perc., backing v, strings. Overdubs added in New York City, April 13, 1960. Produced by Hugo Perretti, Luigi Creatore. RCA Victor 47-7783. RCA Victor Studio A, New York City, January 25, 1960.

13. WORK SONG - Oscar Brown, Jr.

(Oscar Brown, Jr., Nathaniel Adderley aka Nat Adderley)

Billy Butterfield or Joe Wilder-tp; Don Arnone or Everett Barksdale-g; Floyd Morris, Alonzo Levister or Bernie Leighton-p; George Duvivier, Frank Carroll or Joe Benjamin-b; James Johnson as Ossie Johnson, David Panama Francis as Panama Francis, George Devens or Bobbie Rosengardner-d. Columbia CL 1577. June 20, 1960.

14. NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN - Snooks Eaglin

(unknown, arranged by Fird Eaglin, Jr. aka Snooks Eaglin)

Frank Fields-b; Joseph Johnson as Smokey Johnson-d. Imperial 5671. New Orleans, June 27, 1961.

15. ARE YOU SURE - Aretha Franklin

(Robert Meredith Willson)

Aretha Louise Franklin as Aretha Franklin-v, p; Al Sears-ts; Lord Westbrook-g; Milt Hinton-b; Samie Evans as Samuel Evans as Sticks Evans-d.

January 10, 1961.

16. EXODUS - Eddie Harris

(Ernest Siegmund Goldner aka Ernest Gold)

Eddie Harris-ts; Joseph Diorio-g; Willie Pickens-p; William Yancy-b; Harold Jones-d. Vee Jay SR 3016. Chicago, January 17, 1961.

17. MINSTREL AND QUEEN - The Impressions

(Curtis Lee Mayfield II aka Curtis Mayfield)

Curtis Lee Mayfield II as Curtis Mayfield-lead tenor v, possibly g; Fred Cash-tv; Arthur Brooks-tv; Richard Allidan Brooks-tv; Samuel Gooden-b; Roy Glover Orchestra arranged and conducted by Maxwell Davis; d, perc. ABC-Paramount ABC 450. New York City, March 21, 1962.

18. YOU CAN’T JUDGE A BOOK (BY LOOKING AT THE COVER) - Bo Diddley

(Ellas Bates McDaniel as Bo Diddley)

Ellas Bates McDaniel aka Bo Diddley-v, g; Jesse James Johnson or Chester Lindsey-b; Bill Downing or Edell Robertson-d; Jerome Green-maracas. Ter-Mar Recording Studio, Chicago, June 27, 1962.

19. JUDGE HARSH BLUES [aka Good Morning Blues] Furry Lewis

(Walter E. Lewis aka Furry Lewis)

Walter E. Lewis as Furry Lewis-v, slide guitar. Memphis, Tennessee, 1962.

20. WE SHALL OVERCOME - Guy Carawan

(adapted by Zilphia Mae Johnson aka Zilphia Horton, Guy Hughes Carawan, Jr. as Guy Carawan)

Guy Hughes Carawan, Jr.-v, g. Newport Folk Festival, Freebody Park, Rhode Island, June 24, 25 or 26, 1960.

La ligne de couleur a longtemps dominé les relations humaines entre Noirs, Blancs et métis, et les domine encore souvent. Abolie en 1966 aux États-Unis, la ségrégation raciale a été largement évoquée dans les musiques afro-américaines, inspirant des chefs-d’œuvre de dignité, d’humour, de résistance et de spiritualité. Chants de travail, ménestrels au visage noirci, negro spirituals, calypso, jazz, blues, rock et gospel ont rythmé ces expressions d’une intense créativité. Bruno Blum raconte leurs histoires dans un livret de 24 pages, de la Harlem Renaissance au mouvement pour les Droits Civiques, dans ce coffret 59 titres musicaux publié en partenariat avec le musée du quai Branly Jacques Chirac à l’occasion de l’exposition The Color Line à Paris.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The color line has long dominated relations between Blacks, Whites and mixed race, and often still does. Abolished in 1966 in the USA, racial segregation was widely evoked in African-American musics, inspiring masterpieces of dignity, humour, resistance and spirituality. Work songs, blackface minstrels, negro spirituals, calypso, jazz, blues, rock and gospel gave a beat to these intensely creative expressions. In partnership with the Musée du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac, on the occasion of “The Color Line” exhibition in Paris, Bruno Blum tells the story of these 59 titles, from the Harlem Renaissance to the Civil-Rights movement, in a 24-page booklet.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CD 1 - 1916-1948 : 1. ROLL ON, HEAVE THAT COTTON - Harry C. Browne 2’55 • 2. OH! SUSANNA - Harry C. Browne 3’35 • 3. ETHIOPIA SHALL STRETCH FORTH HER HANDS ONTO GOD - Marcus Garvey 3,01 • 4. WE LOVE HUMANITY - Marcus Garvey 0’14 • 5. BLACK AND TAN FANTASY - Duke Ellington 3’18 • 6. DRY BONE SHUFFLE - Arthur “Blind” Blake 2’37 • 7. THE AMERICAN WOMAN AND THE WEST INDIAN MAN Pt. 1 - Sam Manning 3’21 • 8. THE AMERICAN WOMAN AND THE WEST INDIAN MAN Pt. 2 - Sam Manning 2’54 • 9. HIGH SOCIETY - Monk Hazel 3’00 • 10. CHICAGO HIGH LIFE - Earl Hines 2’50 • 11. MY MAMMY - Al Jolson 3’11 • 12. W. P. A. BLUES - Casey Bill Weldon 3’18 • 13. THE BOURGEOIS BLUES - Lead Belly 2’18 • 14. TARZAN OF HARLEM - Cab Calloway 2’48 • 15. STRANGE FRUIT - Billie Holiday 3’12 • 16. PARCHMAN FARM BLUES - Bukka White 2’38 • 17. TROUBLE - Josh White 3’19 • 18. UNCLE SAM SAYS - Josh White 2’41 • 19. OLD ALABAMA - B. B. E. 3’01 • 20. EARLY IN THE MORNING - 22 4’40.

CD 2 - 1944-1958 : 1. JIM CROW - The Union Boys 2’47 • 2. JIM CROW BLUES - Lead Belly 2’23 • BLACK, BROWN AND BEIGE - Duke Ellington • 3. a) WORK SONG 4’41 • 4. b) COME SUNDAY 4’34 • 5. c) THE BLUES 4’39 • 6. d) THREE DANCES 4’28 • 7. WATER BOY - Paul Robeson 2’32 • 8. PRISON BLUES - Alex 2’24 • 9. HARD ROAD BLUES - Floyd Dixon 3’15 • 10. BLACK, BROWN AND WHITE [Get Back] - Big Bill Broonzy (live) 2’51 • 11. BROWN SKIN WOMEN - Howlin’ Wolf 2’44 • 12. LOW SOCIETY - Ray Charles 2’52 • 13. I’VE BEEN BORN AGAIN - The Blind Boys of Alabama 2’53 • 14. BLACK AND TAN FANTASY - Thelonious Monk 3’25 • 15. NO ROOM AT THE INN - Mahalia Jackson 4’18 • 16. THE ALABAMA BUS Pts 1 & 2 - Brother Will Hairston 4’31 • 17. JIM CROW TRAIN - Josh White 2’48 • 18. STAR-O - Harry Belafonte 2’03 • 19. BROWN SKIN GIRL - Lloyd Prince Thomas 3’12 • 20. GOLD COAST - John Coltrane 14’39.

CD 3 - 1956-1962 : 1. BROWN EYED HANDSOME MAN - Chuck Berry 2’17 • 2. SAY BOSS MAN - Bo Diddley 2’30 • 3. NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN - Louis Armstrong 3’01 • 4. THE GREAT GRANDFATHER - Bo Diddley 2’27 • 5. BETTER GIT IT IN YOUR SOUL - Charles Mingus 7’23 • 6. KIYAKIYA [Why Do You Run Away?] - Babatunde Olatunji 4’14 • 7. CARRIE BELLE - John Davis 3’37 • 8. WORKING MAN - Bo Diddley 2’31 • 9. ANCIENT AETHIOPIA - Sun Ra 9’04 • 10. GEORGIA ON MY MIND - Ray Charles 3’34 • 11. DEATH DON’T HAVE NO MERCY - Reverend Gary Davis 4’40 • 12. CHAIN GANG - Sam Cooke 2’34 • 13. WORK SONG - Oscar Brown, Jr. 2’34 • 14. NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN - Snooks Eaglin 2’16 • 15. ARE YOU SURE - Aretha Franklin 2’42 • 16. EXODUS - Eddie Harris 6’39 • 17. MINSTREL AND QUEEN - The Impressions 2’21 • 18. YOU CAN’T JUDGE A BOOK (By Looking at the Cover) - Bo Diddley 3’13 • 19. JUDGE HARSH BLUES - Furry Lewis 5’30 • 20. WE SHALL OVERCOME - Guy Carawan 3’40.