- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

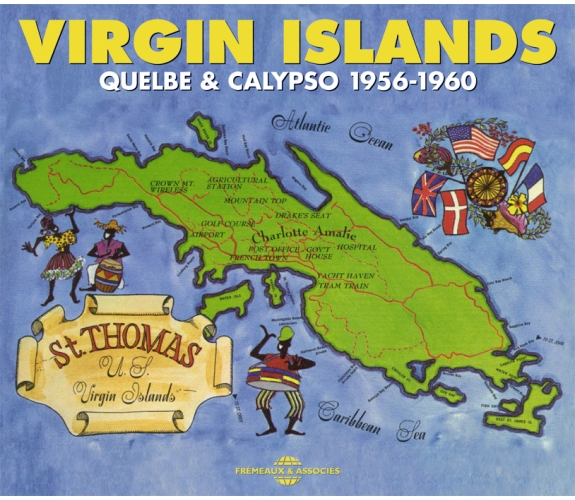

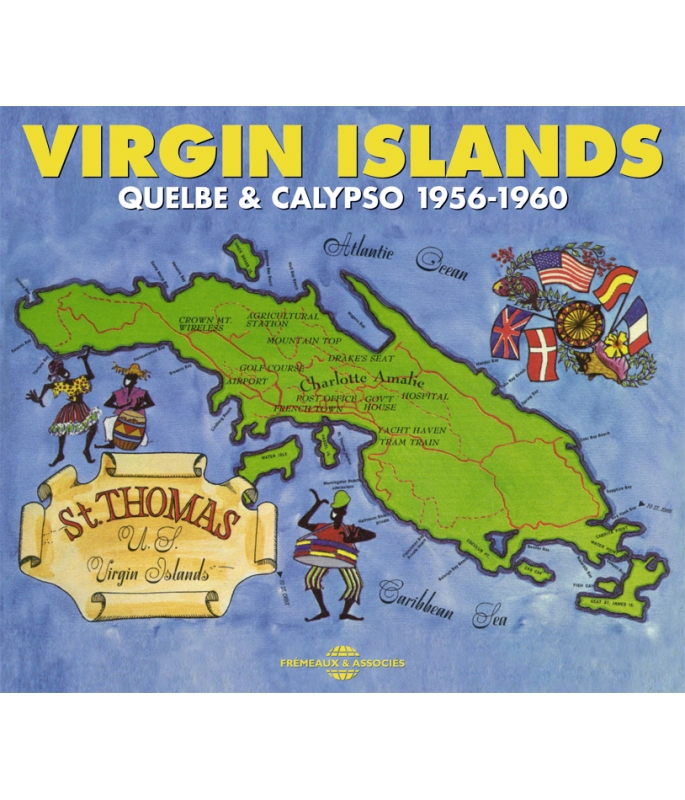

VIRGIN ISLANDS - QUELBE & CALYPSO (1956-1960)

Ref.: FA5403

Direction Artistique : BRUNO BLUM & FABRICE URIAC

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 2 heures

Nbre. CD : 2

VIRGIN ISLANDS - QUELBE & CALYPSO (1956-1960)

Situées au large de la Floride, les Îles Vierges font partie du territoire américain. Mais qui connaît l’étonnante musique jouée par ces habitants ? Un lien direct entre l’Afrique et l’Amérique brille dans le son particulier de ces chansons imprégnées de vaudou. Avec la participation de Fabrice Uriac, Bruno Blum a découvert et commenté ces rares enregistrements miraculeusement surgis entre Îles Vierges britanniques et portoricaines. Le témoignage original et irrésistible d’un aspect ignoré de la musique des États-Unis : celle des Caraïbes américaines.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The western Virgin Islands are American territory, but who has heard the astonishing music played by its inhabitants? The special sound of these songs is impregnated with voodoo and a direct link between Africa and America; with the help of Fabrice Uriac, Bruno Blum has compiled some rare recordings which miraculously sprang from this source lying between the British and Puerto Rican Virgin Islands, and this anthology reveals an original, often-ignored but irresistible aspect of American music from the middle of the Caribbean.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : BRUNO BLUM, AVEC LA PARTICIPATION DE FABRICE URIAC.

DROITS : DP / FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

DISC 1 : ROOKOMBEY - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS W/CALYPSO TROUBADOURS • OBEAH MAN - ALWYN RICHARDS W/ST. THOMAS CALYPSO ORCHESTRA • ALFREDO BOY - BILL FLEMING W/ LA MOTTA BROTHERS & VIRGIN ISLANDERS • VIRGIN ISLE COUNTRY DANCE - ARCHIE THOMAS W/ ST. CROIX ORCHESTRA • CLIMBING THE MOUNTAIN - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS • YO’ GOT TO KNOW WHAT TO DO - BILL FLEMING • CASH, CASH ME BALL - ALWYN RICHARDS • HINDU CALYPSO - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS • ONE GONE – UNKNOWN • MONEY HONEY - THE FABULOUS MCCLEVERTYS • NAZALIN AND HER MANDOLIN - BILL FLEMING • TEASE ’EM SQUEEZE ’EM - BILL FLEMING • THE PING PONG - THE MIGHTY ZEBRA W/LA MOTTA BROTHERS & VIRGIN ISLES ORCHESTRA • SCANDAL IN ST. THOMAS - THE MIGHTY ZEBRA • HOW YO’ KNOW WHAT I GOT - BILL FLEMING • NOTHING VENTURED, NOTHING GAINED - BILL FLEMING• PAN BUSH MARY - ARCHIE THOMAS • PARAKEETS - THE FABULOUS MCCLEVERTYS • SCRATCH, SCRATCH MY BACK - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS • BIG CONFUSION - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS • WEST END ROMANCE - ARCHIE THOMAS • TOUCH IT - UNKNOWN. DISC 2 : ROOKOMBAY - THE FABULOUS MCCLEVERTYS • CHICKEN GUMBO - THE FABULOUS MCCLEVERTYS • VOODOO WOMAN - BILL FLEMING • ENGLISHMAN’S DIPLOMACY - THE MIGHTY ZEBRA • WE LIKE IKE - THE MIGHTY ZEBRA • BREAKFAST IN A FLYING SAUCER - BILL FLEMING • VIM VIGOR AND VITALITY - BILL FLEMING • CREOLE GAL - THE DUKE OF IRON • FOOLISH MAN - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS • BROWN SKIN GIRL - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS • HIT AND RUN - ALWYN RICHARDS • KUM TO PAPIE - ALWYN RICHARDS • I WENT TO COLLEGE - THE MIGHTY ZEBRA • THE FEMALE WOODCUTTER - THE MIGHTY ZEBRA • DO FOR DO - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS • MOCO JOE - LLOYD PRINCE THOMAS • TICKLE, TICKLE - THE FABULOUS MCCLEVERTYS • DON’T BLAME IT ON ELVIS - THE FABULOUS MCCLEVERTYS • WATCH CALLA FROM GUATEMALA - BILL FLEMING • 20. STOP THE BOAT - BILL FLEMING • COLDEST WOMAN - THE FABULOUS MCCLEVERTYS • PALMA DUMPLIN’ - ARCHIE THOMAS • KILL THING PAPPY - ARCHIE THOMAS

THE KINGSTON RECORDINGS 1951-1958

Lord Kitchener, Mighty Sparrow, Lord Invader, King...

GOMBEY & CALYPSO 1953-1960

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1RookombayLloyd Prince Thomas & Calypso TroubadorsIrving Burgie00:03:051956

-

2Obeah ManAlwyn Richards & St Thomas Calypso OrchestraAlwyn Richards00:02:231960

-

3Alfredo BoyBill Fleming & La Motta Brothers & Virgin IslandersWillbur La Motta00:02:291956

-

4Virgin Isle, Country DanceArchie Thomas & St Croix OrchestraArchibald Thomas00:02:361960

-

5Climbing The MountainLloyd Price ThomasLloyd Thomas00:02:591957

-

6Yo Got To Know What To DoBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:371956

-

7Cash Cash Me BallAlwyn RichardsAlwyn Richards00:03:101960

-

8Hindu CalypsoLloyd Price ThomasLloyd Thomas00:03:131957

-

9One GoneInconnusInconnu00:02:501956

-

10Money HoneyThe Fabulous McClevertysCivial00:02:091957

-

11Nazalin and Her MandolinBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:441956

-

12Tease 'Em Queeze 'EmBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:261956

-

13The Ping PongThe Mighty Zebra & La Motta Brothers & Virgin IslandersCharles Harris00:02:341956

-

14Scandal in Saint ThomasThe Mighty ZebraCharles Harris00:02:571956

-

15How You Know What I GotBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:391956

-

16Nothing Ventured, Nothing GainedBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:291956

-

17Pan Bush MaryArchie ThomasArchibald Thomas00:02:441960

-

18ParakeetsThe Fabulous McClevertysManny Warner00:02:011957

-

19Scratch, Scratch My BackLloyd Price ThomasLloyd Thomas00:02:501957

-

20Big ConfusionLloyd Price ThomasLloyd Thomas00:02:561957

-

21West End RomanceArchie ThomasArchibald Thomas00:02:451960

-

22Touch ItInconnusInconnu00:03:031956

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1RookombayThe Fabulous McClevertysIrving Burgie00:03:171957

-

2Chicken GumboThe Fabulous McClevertysIrving Burgie00:02:171957

-

3Voodoo WomanBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:221956

-

4Englishman's DiplomacyThe Mighty ZebraCharles Harris00:02:531956

-

5We Like IkeThe Mighty ZebraCharles Harris00:03:011956

-

6Breakfast in a Flying SaucerBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:041956

-

7Vim Vigor and VitalityBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:261956

-

8Creole GalThe Duke of IronCecil Anderson00:02:391957

-

9Foolish ManLloyd Price ThomasLloyd Thomas00:02:431957

-

10Brown Skin GirlLloyd Price ThomasLloyd Thomas00:03:151957

-

11Hit And RunAlwyn RichardsAlwyn Richards00:02:451960

-

12Kum To PapieAlwyn RichardsAlwyn Richards00:03:171960

-

13I Went To CollegeThe Mighty ZebraCharles Harris00:02:581956

-

14The Female WoodcutterThe Mighty ZebraCharles Harris00:03:031956

-

15Do For DoLloyd Price ThomasLloyd Thomas00:03:041957

-

16Moco JoeLloyd Price ThomasLloyd Thomas00:02:521957

-

17Tickle TickleThe Fabulous McClevertysManning00:01:571957

-

18Don't Blame It On ElvisThe Fabulous McClevertysManning00:02:341957

-

19Watch Calla From GuatemalaBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:221956

-

20Stop The BoatBill FlemingWillbur La Motta00:02:261956

-

21Coldest WomanThe Fabulous McClevertysWarner00:02:151957

-

22Palma Dumplin'Archie ThomasArchibald Thomas00:02:201960

-

23Kill Thing PapyArchie ThomasArchibald Thomas00:02:241960

Virgin islands FA5403

VIRGIN ISLANDS

QUELBE & CALYPSO 1956-1960

Par Bruno Blum

Situé dans les îles Sous-le-Vent (vent qui souffle du sud-est) entre Saint Martin et Porto Rico au cœur des Caraïbes, l’archipel des Îles Vierges est divisé en trois territoires distincts. Les îles de l’est dépendent du Royaume-Uni (îles Tortola, Virgin Gorda, Anegada, etc.). Après avoir été longuement disputées par des pirates (dont le légendaire Barbe-Noire) et boucaniers français, néerlandais et espagnols, elles sont devenues un paradis fiscal : les sociétés installées aux British Virgin Islands ne payent presque aucune taxe.

Les îles du centre de l’archipel ont été annexées par les États-Unis pendant leur guerre contre l’Espagne, et sont depuis 1898 un territoire américain (St. Thomas, St. John, St. Croix, etc.). La loi américaine est appliquée aux U.S. Virgin Islands, mais elles ne font pas partie du pays à 100 %. Elles relèvent d’un statut hérité de l’âge colonial (unincorporated U.S. territory). À l’ouest, les Îles Vierges Espagnoles de Culebra et Vieques (ou Îles du Passage) font partie de Porto Rico, qui est également un territoire d’outremer des États-Unis. Le dollar est la monnaie officielle de tout l’archipel — pour ne pas dire de toute la région. Avec son humour sarcastique de proxénète amateur, la chanson Englisman’s Diplomacy du Trinidadien The Mighty Zebra (installé aux Îles Vierges après un engagement vers 1952) compare les Anglais et les Américains. Le chanteur estime qu’à tout choisir il préfère voir sa petite amie sortir avec un Américain plutôt qu’avec un Anglais car avec leurs belles paroles, les Anglais sont capables de « pénétrer ses défenses » mais ne paieront « même pas une bière », tandis qu’un Américain moins charmeur paiera au moins un bon prix. La fille rapportera alors de l’argent à la maison…

Paradis fiscal et tropical

Les îles furent baptisées Sainte Ursule et les Onze Mille Vierges (raccourci en « Vierges ») par Christophe Colomb qui les découvrit en 1493. Après avoir cruellement exterminé les Indiens, différentes nations européennes y ont déporté des Africains du Ghana, Sénégal, Nigeria, Congo et de la Gambie et les ont réduits en esclavage. Les musiques, langues et cultures africaines n’étaient pas autorisées mais plusieurs cultes des esprits et traditions animistes ont tant bien que mal survécu et résisté à l’oppression. Le travail des esclaves a fait de l’archipel un producteur de canne à sucre, notamment pour les entrepreneurs danois qui avaient colonisé St. Croix et St. John, deux îles cédées aux États-Unis en 1917. Avec cet achat américain, la culture cosmopolite des États-Unis s’est mélangée un peu plus à des éléments bantous, yorubas, akan, danois, français, néerlandais, espagnols et anglais. Majoritairement peuplées par des descendants d’Africains, les Îles Vierges connaissaient au début du XXe siècle une misère endémique. Elles ont vite basculé vers une cohabitation entre paradis tropical pour touristes aisés et paradis fiscal pour sociétés transnationales très aisées. On retrouve une histoire très proche aux Bahamas4, aux Bermudes6 et aux Îles Caïmans, à Nevis, Turks et Caïcos, Barbade et Anguilla, toutes d’anciennes colonies anglaises de la région où l’évasion fiscale se porte bien. Des Arabes et des Indiens se sont aussi installés à St. Thomas, comme en témoigne le remarquable Hindu Calypso de Lloyd Prince Thomas qui y raconte qu’il s’est un jour déguisé en hindou. La révolution cubaine de 1959 a détourné l’afflux de nombreux vacanciers vers les magnifiques Îles Vierges. Avec leurs immenses plages de sable blanc et le développement de l’aviation civile, elles sont devenues une destination touristique dès les années 1940. À trois heures d’avion de Miami, elles concurrencent depuis les Keys, les Bahamas, les Bermudes, la Jamaïque, Saint Martin, Saint Domingue, Anguilla etc. Dans les hôtels de ces îles, on pouvait écouter jouer la musique antillaise à la mode : le calypso.

Le calypso est originaire de Trinité-et-Tobago, un pays insulaire situé à l’extrême sud des Antilles et marqué par une forte immigration francophone de la Martinique, où l’on chantait notamment dans les styles bel air et biguine1. Les disques RCA Victor et Decca s’étaient implantés à la Trinité dès les années 1910. Mélange de cultures africaines et européennes, ces disques de calypso ont circulé très tôt (au même moment que les premiers jazz et blues américains enregistrés, et même avant). Ils ont ainsi été les premiers à marquer la musique caraïbe, jusqu’au-delà de la Nouvelle Orléans2. Dans les années qui ont suivi la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, les musiques exotiques (rumba, cha cha cha, mambo, etc.) étaient en vogue et le calypso connaissait un succès grandissant : la musique était dansante, les mélodies gaies et les paroles toujours soignées, pleines d’un humour parfois salace — idéal pour les vacances. Les musiciens noirs trouvaient difficilement du travail, et pour beaucoup la mode calypso a été l’occasion d’accéder enfin aux scènes des hôtels7.

En 1956 l’excellent album Calypso d’un new-yorkais d’origine jamaïcaine, Harry Belafonte, a fait connaître ce genre au grand public du monde entier3. Avec les énormes ventes de disques du séduisant Belafonte devenu acteur vedette, la demande en calypso était grande et plusieurs maisons de disques américaines ont recherché des artistes susceptibles de profiter de cette mode. Nombre de vedettes internationales ont enregistré dans ce style, parmi lesquels les Andrew Sisters, Robert Mitchum et Henri Salvador4. À Los Angeles les disques Capitol ont lancé le Jamaïcain Lord Flea avec un certain succès sous l’étiquette calypso ; le label Elektra de Jac Holzman (futur producteur des Doors) a sorti des albums de calypso ; de plus petites marques, comme les disques Art de Harold Doane à Miami ont publié des disques des Bahamas, notamment les classiques de Blind Blake5. À Londres, le label Melodisc d’Emil Shalit était spécialisé dans la musique des Antilles. Shalit était concurrencé par la société anglaise Decca, qui fabriquait et diffusait de remarquables disques de mento (Count Lasher, les Ticklers, les Wrigglers, etc.) enregistrés en Jamaïque pour les petits labels locaux de Stanley Motta, Ken Khouri6 … et vendus sous le nom de calypso.

Le calypso était en demande dans toutes les Caraïbes, jusqu’au Bermudes situées en plein océan Atlantique7. Les hôtels engageaient les musiciens capables de jouer les classiques du genre, comme Brown Skin Girl. Cette chanson rendue célèbre par Belafonte et interprétée ici par Lloyd Prince Thomas raconte le calvaire des femmes enceintes abandonnées par les touristes.

En souvenir de leur séjour, les vacanciers achetaient volontiers les disques des groupes attitrés des hôtels, aux pochettes chatoyantes, ce qui créa une opportunité pour de petites entreprises comme Bermuda Records à Hamilton. La demande était analogue aux Îles Vierges, où des musiciens de quelbe local ont introduit des classiques du calypso trinidadien à leur répertoire.

À New York, les disques Monogram de Manny Warner ont publié à cette époque un grand nombre de productions des Caraïbes latines et anglophones. L’album Calypso Holiday en partie réédité ici contient des enregistrements de qualité de chanteurs devenus depuis complètement obscurs, tels Alwyn Richards et Archie Thomas. Comme chez RCA Victor, le souci de Manny Warner était de réaliser des productions très professionnelles, au son impeccable, capables de concurrencer de gros vendeurs à la mode comme Belafonte, Perry Como ou Elvis Presley. Le jeune roi du rock était alors aux prises avec le scandale de ses mouvements de danse jugés trop suggestifs par certains et beaucoup pariaient sur sa chute8. Cet épisode est évoqué ici sur Don’t Blame It on Elvis par les Fabulous McClevertys qui estiment qu’Elvis n’a pas été le premier à danser aussi bien — et de façon aussi érotique — , et que d’autres avaient fait ça bien avant lui (sous entendu : les musiciens noirs) :

Ne reprochez pas à Elvis/De remuer son pelvis /Secouer le pelvis est à la mode/Depuis que le Nil existe

Installé à New York après la guerre, Lloyd Prince Thomas a été le premier musicien des Îles Vierges à être connu pour ses calypsos. Il sortit en 1956 et 1957 deux albums Calypso from Trinidad et Calypso from Jamaica, très vraisemblablement enregistrés à New York où il vivait, et où le calypso était apprécié. Cette anthologie montre bien l’ambivalence entre le quelbe, musique locale des Îles Vierges, et le calypso dans sa version grand public, enregistrée dans les grands studios de New York. Selon les Versatones, un groupe de protégés de Belafonte, « Le calypso a un rythme soutenu mais des mélodies monotones, sans intérêt ». Pour eux, « Les Américains ont essayé de le rendre plus intéressant musicalement ».

À New York, Manny Warner des disques Monogram allait plus loin : « pour le grand public, certaines chansons calypso doivent être faites sur mesure. Le calypso authentique est un médium folk qui parle de problèmes locaux en utilisant le patois des îles. Une grande partie de son sens est perdu quand il est écouté par les masses américaines ». Comme Irving Burgie avec Belafonte, et selon une pratique courante à l’époque, Warner a décidé de signer lui-même des chansons et de les déposer pour profiter des revenus de l’édition musicale. Il s’auto-attribua ainsi la paternité du Big Bamboo de Duke of Iron2 et de Parakeets, sans doute une vieille chanson trinidadienne. Une version des Fabulous McClevertys est incluse ici. Typique du calypso salace, Parakeets évoque la jolie poitrine (les « perroquets ») d’une dame. Une partie des morceaux entendus ici ont cependant été « nettoyés » pour toucher le grand public des États-Unis. Si quelques éléments ont sans doute été perdus dans la traduction, il est probable que l’ensemble soit resté à peu près intact, sans dénaturer son identité proche du quelbe local. En fait cette musique a surtout gagné en qualité en ayant accès à de très bons arrangeurs et ingénieurs du son new-Yorkais. Pour s’en convaincre, il suffit de comparer les morceaux inclus ici à Creole Gal, Touch It et One Gone, tous trois enregistrés à St. Thomas dans des conditions beaucoup plus précaires. C’est The Duke of Iron, un célèbre calypsonien de la Trinité séjournant comme Mighty Zebra aux Îles Vierges, qui chante Creole Girl, extrait d’un mystérieux disque 25 cm dont nous avons inclus ici deux titres interprétés par des chanteurs non crédités.

Jean Ferdulli, fondateur en 1953 à l’instigation de Manny Warner de la boîte de nuit calypso Blue Angel de Chicago, l’une des premières à faire connaître cette musique, a déclaré quelque peu prophétiquement au magazine Ebony : « Le calypso doit être traité avec respect. Il doit être embelli et mis en valeur. Il doit être bien présenté sinon il disparaîtra ». Effectivement plus d’un demi-siècle plus tard — et malgré les succès de Belafonte — le calypso se fera rare. L’irruption dans les années 1950 de la télévision, de la radio et la multiplication des disques accentuera les influences internationales aux Caraïbes : steel bands trinidadiens, musiques américaines et bientôt reggae, soca, etc. Il se diluera beaucoup plus dans la période qui suivra celle entendue ici. À bien des égards, et en dépit des influences entendues ici qui font de toute façon partie de son identité antillaise cosmopolite, cet album représente donc une photographie du quelbe/calypso des Îles Vierges à un stade relativement pur.

Mighty Zebra

La musique populaire des îles a été nourrie par différents apports caribéens, du mento de Jamaïque au calypso de la Trinité. La présence du trinidadien Mighty Zebra a joué son rôle. Né à la Grenade vers 1927 et émigré à la Trinité pendant son enfance, il fit activement partie de la légendaire Young Brigade de Mighty Sparrow2 à Port-of-Spain où il chanta le calypso No Pan, No Pan dès 1948. Il trouva un engagement aux Îles Vierges vers 1952 et y resta au moins jusqu’en 1959, où il rentra à la Trinité pour interpréter sa chanson Jamaica and the Federation (la Fédération des Indes Occidentales9, qui fut un échec). Par la suite Zebra continuera ses activités dans l’Original Young Brigade à la Trinité. En 1956 à New York il a gravé un album pour les disques RCA avec l’équipe des frères LaMotta, qui l’accompagnaient sur scène à l’hôtel Virgin Isles. Influent dans l’archipel, Zebra chante ici six titres bien construits, aux paroles soignées et humoristiques comme toujours dans le calypso. Sur I Went to College il prétend être cultivé mais montre le contraire en faisant de grosses fautes quand il épelle des mots. Sur Ping Pong il essaye de séduire une joueuse de bidons dans un steel band, mais elle refuse ses avances en raison de sa trop grosse « baguette ». Et sur We Like Ike, il félicite le président Dwight Eisenhower pour sa réélection du 6 novembre 1956. Zebra avait pris parti pour la droite américaine, qui cherchait à manipuler les musiciens populaires à des fins électorales. Ce fut aussi le cas pour son mentor Mighty Sparrow à la Trinité, lui aussi engagé dans le camp conservateur à qui il consacra plusieurs apologies.

Quelbe

Le quelbe est la véritable musique populaire nationale des Îles Vierges. Réputé remonter aux temps de l’esclavage, il précéda la mode du calypso. Le schéma a été le même en Jamaïque, où la musique populaire du XXe siècle s’appelait le mento6 avant la mode calypso, et aux Bahamas, où elle s’appelait le goombay5. En réalité tous ces styles se sont mélangés au hasard des transports maritimes, des concerts de diverses musiques caribéennes et de la diffusion des disques. Le calypso et le quelbe peuvent être facilement confondus, mais bien qu’ils plongent tous deux leurs racines jusqu’en Afrique, ils sont en principe distincts. On trouve sans doute une vraie fusion musicale avec le quelbe sur Virgin Isle Country Dance d’Archie Thomas, One Gone et Hindu Calypso de Lloyd Prince Thomas par exemple, et sur plusieurs autres titres. Comme le calypso trinidadien et le mento jamaïcain, le quelbe aborde volontiers des thématiques sexuelles, avec ses double sens « hokum » salaces héritées de la tradition des Black Face Minstrels, comme sur Parakeets, The Female Wood Cutter, Ping Pong ou Vim Vigor and Vitality, et des questions d’actualité sociales, politiques ou religieuses. Sur One Gone, le chanteur raconte l’histoire d’un prêtre baptiste qui bat son fils Jonah, dont il pense qu’il a volé un ticket de tiercé (sweepstake). Le style afro-caribéen quelbe des Îles Vierges sera toujours joué au XXIe siècle à l’occasion d’évènements sociaux, de spectacles pour touristes et dans les cabarets de Charlotte Amalie, capitale des îles américaines. Il sera notamment interprété par James Brewster, dit Jamesie (né en 1929) qui a enregistré plusieurs albums du genre dans les années 1970. Le terme « quelbe » correspond en fait surtout à une étiquette locale. Mais musicalement, il a beaucoup évolué au fil du temps. Les instruments utilisés ont aussi changé, des instruments de fortune de type skiffle/jug band au saxophone jusqu’au matériel électrique etc. À vrai dire, s’il est sans doute apparenté rythmiquement au gombey bermudéen6 et aux rythmes bantous d’Afrique centrale, le quelbe comme le « calypso » des Îles Vierges sont avant tout des musiques spécifiques à l’archipel. Le quelbe/calypso a aussi été marqué par des musiques latines et haïtiennes, et des rythmes et instruments d’Afrique centrale. Répandu à Cuba comme dans la guitare rythmique de Bo Diddley à Chicago10, le rythme de tibois ou clave joué sur Scratch my Back et Big Confusion vient par exemple directement des côtes d’Afrique centrale. Le quelbe est aussi marqué par le gospel américain, qui a influencé la composition de plusieurs titres de Bill LaMotta. Il a aussi — et surtout — assimilé des musiques d’Afrique de l’ouest d’où sont originaires certains rites vaudou.

Scratch, etc

D’autres musiques folkloriques existent dans l’archipel, notamment le scratch, une musique traditionnelle basée sur les percussions. Le scratch est un instrument de bois cannelé, gratté à l’aide d’une baguette comme le guiro portoricain. Également appelé fungi, le scratch est peut-être dérivé d’une musique de ramadan nigériane, le fuji. Particulièrement populaire à St. Croix, l’utilisation d’une scie de menuisier frottée par une baguette de bois se retrouve à Cat Island (rake-and-scrape des Bahamas) et aux îles Turks et Caïcos (ripsaw). Comme toujours aux Antilles les mélanges sont inextricables. Les noms de styles musicaux relèvent plus des étiquettes qu’on leur estampille pour les mettre sur le marché. Inévitablement, le calypso des Îles Vierges a aussi été influencé par Cuba et le merengue de Saint-Domingue et Porto Rico tout proches11.

Certains albums originaux dont sont extraits notre sélection contiennent même des titres de pur merengue chantés en espagnol (non retenus ici). Au début du XXe siècle, la présence de plusieurs groupes de musiciens français venus de St. Barth et installés à St. Thomas, comme Cyril Querrard et ses Mountain Kings, a aussi beaucoup compté. D’autres éléments européens sont aussi présents dans le quelbe et le calypso. À commencer par le quadrille, très populaire à la Guadeloupe, Martinique et Jamaïque, et à St. Croix où il sera joué jusqu’au XXIe siècle.

Un rythme de valse est aussi entendu ici sur le Scandal in St. Thomas de Mighty Zebra. La valse lente a toujours été présente aux Antilles françaises1 et anglophones. En Jamaïque en 1969 Bob Marley enregistrera le sublime Send Me That Love dans ce style, Blind Blake grava The Cigar Song aux Bahamas en 1952, sans oublier le I Put a Spell on You vaudou enregistré en 1956 par Screamin’ Jay Hawkins à New York12.

Vaudou, Orisha, Obeah

La Chrétienté et l’Islam sont des religions artificielles. Artificielles. C’est pour exploiter les gens qu’elles sont répandues dans toute l’Afrique. Tous les chrétiens pensent comme des Blancs, comme les Européens, comme les Anglais et les Américains. Et tous les musulmans pensent comme des Arabes. Vous savez ils ne font que détourner les esprits africains de leurs racines. Les Africains doivent le savoir. Vous voyez, ils devraient avoir leur religion d’origine. Et quelqu’un doit diffuser ce savoir. Je pense que j’ai ce savoir.

Le Yoruba Fela Anikulapo Kuti dans le documentaire Music Is the Weapon (Musique au poing de Jean-Jacques Fiori et Stéphane Tchalgadjieff, 1982).

Au-delà des définitions musicales, les chansons de ce florilège nous plongent avant tout dans le monde fascinant des spiritualités afro-caribéennes, dont les Îles Vierges, situées sur le territoire des États-Unis, étaient avec la Nouvelle-Orléans la tête de pont dans les années 1950. Ces traditions et cette foi résistaient depuis des siècles au lavage de cerveau du conservatisme et colonialisme américain — parfois en se fondant discrètement derrière une façade chrétienne. Alors qu’en 1956 les États-Unis étaient frappés par les premières convulsions du mouvement de libération afro-américain (le Mouvement des Droits Civiques mené par le pasteur baptiste Martin Luther King), les cultes afro-caribéens des esprits des morts rejetés par les ecclésiastiques chrétiens étaient pratiqués par une bonne partie de la population des Îles Vierges.

La proximité de Saint-Domingue — et de Haïti, où le vaudou a littéralement structuré la société (après une longue et sanglante révolution, Haïti avait obtenu son indépendance en 1804) — a contribué à la présence aux Îles Vierges de ces mystérieux éléments typiquement afro-caribéens. Bien que l’essentiel de ces pratiques soient restées plus ou moins discrètes, voire secrètes en raison de leur rejet par les autorités coloniales, elles ont perduré, et ce longtemps au péril de la vie des résistants. En 1960, comme aux proches îles Bahamas4 elles faisaient presque ouvertement partie de la société. Au moins huit titres de cette anthologie font une allusion directe aux cultes des esprits des défunts rejetés par Jésus selon la Bible : vaudou (originaire des actuels Bénin et Nigeria), orisha (culte yoruba de l’ouest du Nigeria, que l’on retrouve à la Trinité), obeah (notamment pratiqué par les Ashantis au Ghana actuel) et différentes influences bantoues : sont inclus ici Obeah Man, Alfredo Boy, Chicken Gumbo, Voodoo Woman, Do for Do et deux versions de Rookombey. Quant à Big Confusion, il décrit un combat entre un pasteur chrétien et un stickman qui a recours à des pratiques occultes (on attribue à la terre des cimetières une puissance spirituelle) : La poupée en caoutchouc a été au cimetière et a ramassé du sable.

Ces formes de spiritualité étaient mal considérées, souvent réduites à des stéréotypes de séduction, d’envoûtement, de zombies (ou « jumbies ») — mais sont restées profondément implantées. Sur le splendide Obeah Man, Alwyn Richards supplie par exemple le prêtre de le libérer du vaudou « qu’il ne supporte plus ». Le style s’apparente ici moins au calypso qu’au quelbe traditionnel. Sur Do for Do, Lloyd Prince Thomas chante que pendant que sa femme le trompe, il fait pareil qu’elle avec l’aide de l’obeah.

RookombAy

Les deux magnifiques versions de Rookombay incluses ici racontent une soirée orisha où Shango, une divinité yoruba, est évoqué :

Une nuit j’ai tenté ma chance/J’ai été à une danse vaudou/Je voulais une nouvelle romance/C’est pourquoi j’ai été à une danse Shango/Le grand prêtre avait l’air très sévère/Quand il est apparu sur la scène/Il a fait un geste/Et j’ai commencé la cérémonie/Le chant disait : rookombey Zelma […] Une vieille dame vivait dans une tombe avec dix zombies/Elle avait une calebasse en main et versait de l’huile de serpent/Sur l’homme vaudou

La chanson raconte ensuite qu’une Grande Prétresse nommée Naomi n’avait « pas un cheveu sur la tête et ressemblait à Boris Karloff dans Le Mort qui Marche » (The Walking Dead, Michael Curtiz, 1936). Rookombay est signé d’un pseudonyme d’Irving Burgie, un musicien de calypso né à New York et connu sous le nom de Lord Burgess. Son père venait de Virginie et sa mère de la Barbade, une île britannique des Caraïbes. Burgess s’était spécialisé dans la reprise de chansons traditionnelles des Caraïbes qu’il dénichait en fréquentant des musiciens antillais, et adaptait leurs paroles au grand public américain. Il a fait fortune en s’attribuant de nombreuses mélodies antillaises qu’il a été le premier à déposer, cosignant notamment Day O et Jamaica Farewell, deux énormes succès de son collaborateur Harry Belafonte chez RCA. C’est d’ailleurs le producteur du Day O de Belafonte, Herman Diaz Jr., qui a réalisé pour RCA l’album du Mighty Zebra dont on peut écouter ici les meilleurs extraits. Comme Rookombey, Chicken Gumbo fait allusion au vaudou. Ces deux titres ont également été enregistrés par la divine Josephine Premice, une new-yorkaise d’origine haïtienne12. Venu d’Afrique, le vaudou/obeah s’est répandu aux Caraïbes sans se limiter à la Louisiane et à Haïti, comme il est couramment supposé. Il est présent dans toutes les Amériques sous différentes formes — et sous différents noms12.

The Fabulous McClevertys

Originaires de St. Croix comme Bill LaMotta, les Fabulous McClevertys ont publié un album chez Verve en 1957. Fondé en Californie par Norman Granz en 1956, l’excellent label Verve était spécialisé dans le jazz et une fois vendu à la MGM en 1961, il s’orientera vers des musiques encore plus inattendues, voire expérimentales (comme les Mothers of Invention ou le Velvet Underground). Leurs titres inclus ici suffiraient pour que ces remarquables musiciens de calypso restent dans l’histoire, mais beaucoup retiendront surtout qu’ils ont accompagné jusqu’en 1955 le chanteur américain de calypso The Charmer. La mère de The Charmer était originaire de St. Kitts et Nevis et son père était jamaïcain. The Charmer décida cette année-là de se consacrer à la religion et deviendra quelques années plus tard le leader de la Nation of Islam sous le nom de Louis Farrakhan (en 1955 leur leader Elijah Muhammad considérait que la musique était en contradiction avec les principes de l’Islam). On peut lire cette histoire et entendre The Charmer accompagné par le saxophoniste Johnny McClevertys and his Calypso Boys sur notre anthologie consacrée à la Trinité2. Mais cette anecdote montre surtout que 1955 a été l’année charnière du mouvement de libération des Afro-américains. Certains cherchaient leurs racines africaines dans l’Islam, d’autres dans le mouvement Rastafari qui se développait en Jamaïque, d’autres encore dans divers temples protestants, églises catholiques et cultes revivalistes13.

Les Frères LaMotta

Les hôtels étaient fréquentés à la capitale Charlotte Amalie sur St. Thomas, mais rares étaient les vacanciers qui s’aventuraient par bateau jusqu’à St. Croix, isolée à 40km au sud. L’histoire n’a pas toujours retenu le parcours des artistes de calypso les plus lointains et les plus méconnus. Tous cherchaient à vivre de leur musique dans un contexte difficile d’éloignement. Ils s’efforçaient de développer l’économie de leurs îles perdues, sans grandes ressources. Et au moins l’un d’entre eux a réussi une carrière d’homme d’affaires et de musicien : Bill LaMotta. Son parcours éclaire ce que fut la réalité du calypso des Îles Vierges dans les années 1950.

Wilbur « Bill » LaMotta (13 janvier 1919-9 octobre 1980) est né à St. Croix dans la petite ville de Christiansted, ancienne capitale des Antilles danoises. Né de Wesley et Elisa de la Motta dans une famille de musiciens, le jeune Wilbur a très tôt fait preuve d’aptitudes musicales. Passionné par l’orgue et la clarinette à l’âge de cinq ans, il a vite maîtrisé ces deux instruments et participé aux cérémonies religieuses de l’île en tant que musicien. En 1936, sa composition Heading for Home a été publiée à New York et enregistrée par plusieurs artistes. Ce fut le début d’une prolifique carrière de compositeur (400 titres). Son identité antillaise a fait surface dans plusieurs de ses compositions dont The Last Bamboula, Dawn from a Window, In Paradise, Come Back to the Virgin Islands et Bolero for Don Pablo, dédié au violoncelliste Pablo Casals. Bill a étudié à l’école de musique Juilliard à New York. Il s’est ensuite produit à travers les États-Unis en compagnie du groupe formé avec ses cinq frères Orville, Lawrence, Raymond, Reuben et John (leurs sœurs Dorothy et Isabelle n’en faisaient pas partie). Après différents passages à la télévision et à la radio, ils auraient vers 1940 enregistré pour les disques RCA Victor plusieurs titres contribuant à faire connaître le son des Caraïbes. Après des études d’ingénieur militaire à l’U.S. Navy, Bill LaMotta composa la marche King’s Point Victory qui deviendra l’hymne officiel de la Marine Marchande américaine. Il est devenu électricien puis officier de la Marine Marchande pendant la guerre et séjourna longuement sur le continent où il participa à plusieurs projets, dont certains musicaux. Il a composé en 1956 une série de titres pour le trompettiste Bill Fleming qui les enregistra avec les frères LaMotta à New York. Le groupe accompagna Mighty Zebra quelques jours plus tard aux studios RCA. De retour aux Îles Vierges en 1959, Bill LaMotta est devenu éditeur de musique, fondant Westindy Music Corporation et les trois magasins de musique Music Man où travaillait son fils Leroy. La boutique Guitar Lady était tenue par son épouse Joyce Anduze.

Instruit et acteur de la vie économique de ces îles, le musicien a logiquement glissé vers une carrière plus politique. L’homme d’affaires s’occupa du difficile approvisionnement en eau et en électricité de l’archipel, devint consultant pour les questions artistiques et prit d’autres responsabilités. Très direct, cet homme conservateur s’exprimait franchement et lutta toute sa vie pour l’épanouissement de sa région. Il a reçu plusieurs récompenses pour ses accomplissements dans le domaine du commerce et des arts ; il était directeur de la Chambre de Commerce de St. Croix/St. John à sa mort. Il reçut même une distinction posthume de la Marine Marchande.

Bruno Blum

Remerciements à Fabrice Uriac.

© Frémeaux & Associés

1. Lire le livret et écouter les deux volumes de Biguine, valse et mazurka créoles (1929-1940 et 1930-1943) dans cette collection.

2. Lire le livret et écouter Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5374) dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret et écouter Harry Belafonte Calypso-Mento-Folk 1954-1957 (FA 5234) dans cette collection.

4. Lire le livret et écouter le volume Calypso (FA 5342) de la série Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret et écouter Bahamas - Goombay & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA 5302) dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection.

7. Lire le livret et écouter Bermuda - Gombey & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA 5374).

8. Lire le livret et écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine (1954-1956 et 1956-1958) dans cette collection.

9. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA 5374) dans cette collection.

10. Lire les livrets et écouter les deux volumes de The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 et 1960-1962 (FA 5376 et FA 5405) dans cette collection.

11. Lire le livret et écouter Santo Domingo - Merengue à paraître dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA 5375) dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Folk - Trance - Possession 1939-1961 (FA 5384) dans cette collection.

Located in the Leeward Islands between Saint Martin and Puerto Rico, the archipelago known as the Virgin Islands is divided into three separate territories. The islands to the east—Tortola, Virgin Gorda, Anegada etc.—belong to the United Kingdom, and after long disputes between pirates (the notorious Blackbeard among them) and buccaneers from France, Holland and Spain, they became a tax haven for off-shore companies.

The islands in the centre of the group were annexed by America during the Spanish War and became a U.S. protectorate in 1898. American law still applies on the islands of St. Thomas, St. John, St. Croix etc., due to their statutes as unincorporated U.S. territories. To the west, separated from the others by the Virgin Passage, lie the Spanish/Puerto Rican Virgin Islands of Culebra and Vieques, also U.S. overseas territories (with the U.S. dollar as the legal currency throughout the islands, and even the whole region). The humorous song—the sarcastic humour of an amateur pimp—entitled Englishman’s Diplomacy by Trinidadian The Mighty Zebra (he settled in the Virgin Islands in around 1952) compares Englishmen with Americans: in the singer’s opinion, he’d rather see his girlfriend escorted by an American because an Englishman, a smooth talker, might “penetrate her defences” without paying even a beer, whereas a less charming American would at least pay the right price (and the girl, of course, would dutifully return home with the money).

TROPICAL (FISCAL) ParadisE

The islands were christened Saint Ursula and the Eleven Thousand Virgins (shortened to “Virgins») by Christopher Colombus, who discovered them in 1493. After cruelly exterminating the Indians, various European nations made the islands a destination for Africans deported from Ghana, Senegal, Nigeria, Gambia and The Congo. African music, languages and cultures were banned, but several spirit- and animist-cultures managed to survive despite slaves oppression. Slave labour made the islands a producer of sugarcane, notably for Danish entrepreneurs who colonized St. Croix and St. John, the two islands sold to the USA in 1917. America’s purchase of the islands led to the mingling of its cosmopolitan culture with elements whose origins were Bantu, Yoruba, Akan, Danish, French, Dutch, Spanish and English… For inhabitants whose majority was of African ancestry, the beginning of the 20th century was a period of endemic misery. Tourists seeking a tropical paradise cohabited with rich multinationals in search of a tax haven. History was repeating itself, with similar changes occurring in The Bahamas4, The Bermudas6, The Cayman Islands, Nevis, The Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados and Anguilla, all of them former English colonies where tax evasion was/is a major occupation. Arabs and Indians also settled on St. Thomas, as shown by the remarkable Hindu Calypso from Lloyd Prince Thomas, who tells how he disguised himself as a Hindu. The Cuban Revolution of 1959 turned many would-be “vacationers” away from Castro’s birthplace, and they landed in the magnificent Virgin Islands where white beaches and adequate airports had launched tourism as early as the 1940’s. The islands were three hours from Miami, and already they competed with the Florida Keys, Bahamas, Bermudas, Jamaica, Saint Martin, San Domingo, Anguilla etc, not least because their hotels played fashionable West Indian music: Calypso.

Calypso

Calypso came from Trinidad & Tobago, the islands at the southern tip of the Antilles; they were home to French-speaking immigrants from Martinique, where the main musical styles were bel air and biguine1. RCA Victor and Decca Records had offices in Trinidad as early as the 1910’s, and calypso records—a mixture of African and European cultures—circulated freely there almost as early as the first American jazz and blues records, if not before. Calypso was the first style to spread across the Caribbean, even reaching New Orleans.2 In the years that followed World War II, other exotic music became fashionable (rumba, cha cha cha, mambo, etc.) and calypso remained successful: the music was danceable, the melodies and lyrics—always joyful, often smutty—were carefully put together, especially with tourists in mind. With black musicians having difficulty finding work, calypso was an ideal means of gaining entry to ballrooms in hotels.7

In 1956, a New Yorker of Jamaican origin named Harry Belafonte released the excellent album entitled Calypso, which revealed the genre to the whole world.3 The enormous sales of records by the seductive Belafonte—he became a film-star—led several American record-companies to seek out artists who might profit from the huge calypso-fashion, and many international artists made similar recordings, among them The Andrews Sisters, Robert Mitchum or Frenchman Henri Salvador.4 In Los Angeles, Capitol Records introduced the Jamaican singer Lord Flea as a calypso artist, and he was quite successful; Jac Holzman—later producer of The Doors—released calypso albums on his Elektra label; and many other small labels, like Harold Doane’s Art Records in Miami, released recordings made in The Bahamas, including some Blind Blake classics.5 In London, Emil Shalit’s Melodisc label specialized in West Indian recordings, and one of his competitors was Decca, which released some remarkable Mento recordings by the likes of Count Lasher, The Ticklers or The Wrigglers, all of them made in Jamaica for little local labels (owned by people like Stanley Motta or Ken Khouri)6 who sold them as calypsos.

Demand for calypso stretched across the Caribbean as far as Bermuda in the Atlantic Ocean.7 Hotels hired musicians who could play the genre’s classics, like Brown Skin Girl. Belafonte made the song famous, and here it’s performed by Lloyd Prince Thomas, who relates the ordeals of women made pregnant and abandoned by tourists…

Records made by bands working in hotels were taken home by tourists as souvenirs; their sleeves were gaily-coloured (incidentally creating new business-opportunities for companies like Bermuda Records in Hamilton) and there was similar demand in the Virgin Islands, where local quelbe musicians added Trinidadian calypso classics to their own repertoire.

In New York, Manny Warner’s Monogram label released many Hispanic and English-language classics from the Caribbean. The album Calypso Holiday (partly reissued here) contains quality-recordings made by singers who have since become totally obscure, like Alwyn Richards and Archie Thomas. As for RCA Victor, Manny Warner’s biggest problem was to make professional records with impeccable sound, titles that could compete with top-sellers like Belafonte, Perry Como or Elvis Presley. The latter was surrounded by scandal due to the way he danced, which was (conservatively) judged too suggestive, with many predicting his downfall.8 That episode is mentioned here in Don’t Blame It on Elvis by The Fabulous McClevertys, in whose opinion Elvis wasn’t the first to dance that well—and that erotically—because it had all been done before (meaning, “by black musicians”): Don’t blame it on Elvis / for shaking his pelvis / shaking the pelvis has been in style / ever since the river Nile.

Settled in New York after the war, Lloyd Prince Thomas was the first Virgin Islands musician to become known for his calypsos. In 1956/57 he released the two albums Calypso from Trinidad and Calypso from Jamaica, which were most probably recorded in New York where his music was much appreciated. This anthology shows the ambivalent relationship between quelbe, the local music of the Virgin Islands, and calypso-music (the most popular kind) recorded in the great studios of the Big Apple. According to the Versatones, a group of Belafonte’s protégés, “Authentic calypso was beat-heavy but melodically dull and monotonous… Americans, to their credit, tried to make it musically interesting.»

In New York, Monogram’s Manny Warner went even further: “For the general public, some Calypso songs must be tailor-made. Authentic Calypso, being the folk medium it is, deals with local problems and is delivered in the patois of the Islands. Much of its meaning is lost when presented to a mass American audience.» Like Irving Burgie with Belafonte—the practice was common in those days—Manny Warner put his own name to song-copyrights so that he would receive publishing royalties, including Big Bamboo by Duke of Iron2, and Parakeets, probably an old Trinidadian song, here in a version by the Fabulous McClevertys. A typically lewd calypso, Parakeets is a reference to a woman’s “parrots” (her breasts, in other words). Note that some of the songs here were “cleaned up” for American audiences; no doubt, some meaning was partly “lost in translation” as a result, but on the whole their identity remained intact and close to local quelbe music. The music actually gained in quality once it had access to the excellent arrangers and sound-engineers working in New York, as you can hear when you compare the pieces in this set with three titles—Creole Gal, Touch It and One Gone—which were recorded in St. Thomas in much more precarious conditions. Creole Girl is sung by The Duke of Iron, a famous calypso-artist from Trinidad who, like Mighty Zebra, stayed in the Virgin Islands for a while; the song is taken from a mysterious 10” record along with two others performed by singers whose names didn’t receive a single mention.

Encouraged by Manny Warner, Jean Ferdulli founded Chicago’s Blue Angel “calypso” club in 1953, one of the first to feature the style; he declared—somewhat prophetically—in Ebony magazine that, “Calypso must be treated with respect… it must be embellished and glamorized. It must be packaged correctly. If it is not treated with respect,” he went on, “I believe it will die.” Indeed. Half a century later, despite Belafonte’s success, calypso became all too rare. In the Fifties, television, radio and records spread foreign influences across the Caribbean, from Trinidadian steel bands and later to reggae and soca music. Calypso became even more diluted in the period which followed the years represented in this set. In many respects, and despite the influences heard here—which, in any case, are integral to the cosmopolitan identity of the West Indies—this anthology can be seen as a portrait of the Virgin Islands’ quelbe/calypso music in its relatively pure state.

Mighty Zebra

The islands’ popular music was nourished by various West Indian contributions from Jamaican Mento to Trinidadian Calypso, where Mighty Zebra played his part. Born in Grenada in around 1927 and raised in Trinidad as a child, he had an active role in the legendary Young Brigade of Mighty Sparrow2 in Port-of-Spain, where by 1948 he had been noticed with the calypso No Pan, No Pan. He found work in the Virgin Islands in 1952, and stayed at least seven years before he returned to Trinidad with his song Jamaica and the Federation [the Federation of the West Indies9 was a short-lived union between U.K. Commonwealth territories in the Caribbean.] Zebra later continued to be active with the Original Young Brigade on Trinidad. In New York in 1956 he cut an album for RCA with the LaMotta brothers’ crew who accompanied him onstage at the Virgin Isles Hotel. An influence throughout the islands, Zebra here sings six well-crafted titles with carefully-chosen lyrics and the humour that typified the calypso. On I Went to College he pretends to be cultivated but demonstrates the opposite in making mistakes when spelling out words; Ping Pong has him trying to seduce a female percussionist in a steel band, but she refuses his advances because his “stick” is too big; and in We Like Ike, Zebra congratulates President Eisenhower for his re-election on November 6th 1956. Zebra sided with the Republicans, who tended to manipulate popular musicians in order to win votes, as was also the case with his mentor Mighty Sparrow from Trinidad, who sided with America’s conservatives and devoted several songs to their cause.

Quelbe

Quelbe is the authentic popular music of the Virgin Islands. Reputed to have originated in the days of slavery, it was followed by the calypso fashion, the same as in Jamaica, where calypso was preceded by the 20th century popular music known as mento6, and in The Bahamas, where the music was called goombay5. In fact, all these styles mingled together with the evolution of maritime connexions, concerts where different Caribbean music was played, and the spread of record-distribution. It’s easy to confuse calypso and quelbe as both have distant African roots, but in principle the two genres are distinct. A true fusion of calypso and quelbe can be found in Archie Thomas’ Virgin Isle Country Dance, or Lloyd Prince Thomas’ One Gone and Hindu Calypso for example. As in Trinidad’s calypsos or the mento songs of Jamaica, sexual themes are a familiar feature of quelbe pieces with their lewd, “hokum” double-entendres inherited from the traditions of Black Face Minstrels—Parakeets, The Female Wood Cutter, Ping Pong or Vim Vigor and Vitality for example—alongside issues that have to do with society, politics or religion. In One Gone, the singer tells the story of a Baptist preacher who’s convinced his son Jonah has stolen a sweepstake-ticket; he gives him a beating. The Afro-Caribbean quelbe style is still commonly played in the Virgin Islands today, a century later, at social events, tourist-shows or in clubs around Charlotte Amalie, the capital (one notable artist was James Brewster, better known as Jamesie, who was born in 1929 and made several albums in the Seventies). The term “quelbe” is actually more of a local label for this kind of music, which considerably evolved over time. The instruments changed too, with saxophones and amplified equipment replacing the original line-up of basic instruments of the type featured in skiffle groups and jug-bands. If the rhythms of quelbe are no doubt related to Bermuda’s gombey6 and the Bantu rhythms of central Africa, both quelbe music and the calypso of the Virgin Islands are specific to that island group. But it’s not that simple: common in Cuba—and in the beat of Bo Diddley’s guitar in Chicago10—the rhythms of the tibois (or clave) played in Scratch my Back and Big Confusion actually come directly from the Gulf of Guinea. Quelbe can also carry American gospel influences (cf. several titles composed by Bill LaMotta) and, perhaps above all, it has assimilated elements of the West African music originating in certain voodoo rituals.

Scratch, AND OTHER STYLES

Other traditional folk styles are present in the islands, particularly the traditional, percussion-based music known as scratch. The instrument which gave the music its name is made from the (extremely hard) wood of the canella tree, which is scraped with a wooden stick like the guiro of Puerto Rico. Also called fungi, scratch music perhaps derives from fuji, the music played during the month of Ramadan in Nigeria. On St. Croix, “scratching” a carpenter’s saw instead of a piece of canella was a popular technique that could be found also on Cat Island (the rake-and-scrape of the Bahamas) as well as in the Turks & Caicos Islands (known as ripsaw). As always in the West Indies, the cross-breeding is inextricable, and the names given to music-styles have more to do with the way they were labelled for sale… The Virgin Islands’ calypsos were also influenced by Cuba and the merengue music of nearby San Domingo and Puerto Rico;11 some of the original albums from which the titles here were chosen also contained pure merengue songs sung in Spanish. At the beginning of the 20th century, another influence was the presence of several groups of French musicians who came from St. Barth to settle on St. Thomas, like Cyril Querrard and his Mountain Kings band. Other European elements also appear in quelbe and calypso, among them the quadrille, which still enjoys popularity in Guadeloupe, Martinique, Jamaica and St. Croix, and in Mighty Zebra’s Scandal in St. Thomas here, uses a waltz rhythm. Slow waltzes have always had a presence in both the French and English-speaking Antilles1. In 1969, in Jamaica, Bob Marley would record the sublime Send Me That Love in this style, after Blind Blake’s The Cigar Song (Bahamas, 1952) and, of course, the unforgettable voodoo title I Put a Spell on You which Screamin’ Jay Hawkins recorded in 1956 in New York.12

VOODOO, Orisha, Obeah

“Christianity and Islam, they are only artificial religions. Artificial. And the reason why Islam and Christianity is spread all over Africa we know is to exploit the people. All Christians think like white, like Europeans, like English and Americans, and all Muslim people think like Arabs. So they’re just diverting African minds from their roots that’s all, you know. Africans must know. You see they must have the original one. And somebody must spread the knowledge of this. I think I have the knowledge.” [Fela Anikulapo Kuti, a Yoruba, in the documentary Music Is the Weapon by Jean-Jacques Fiori and Stéphane Tchalgadjieff, 1982].

Apart from their musical definitions, the songs in this anthology take us deep into the fascinations of the Afro-Caribbean spiritual culture where the Virgin Islands, together with New Orleans, formed a bridgehead in the Fifties. For centuries, the traditions and beliefs of this universe had resisted all attempts at brainwashing made by conservatives and American colonialists, sometimes discreetly concealed beneath a Christian façade. While the United States felt the first convulsions of Afro-American freedom movements in 1956—notably the Civil Rights Movement lead by Baptist Reverend Martin Luther King—Afro-Caribbean rituals worship of the spirits of the dead (rejected by Christian ecclesiastics) were still commonly practised by a large part of the Virgin Islands’ population.

The proximity of Santo Domingo—and Haiti, where voodoo literally formed the structure of society after a long, bloody revolution had led to Haitian independence in 1804—contributed to the presence in the Virgin Islands of these mysterious, typically Afro-Caribbean elements. Although these practices had remained essentially discreet (if not secret) after they were outlawed by colonialists, they still persisted for a long time, at the peril of these resistants’ very existence. In 1960, as in the Bahamas nearby4, they were almost openly a part of society. At least eight titles in this collection contain direct allusions to the spirits of the dead and rituals condemned by Jesus according to The Bible: voodoo (originating in the African region today covered by Benin and Nigeria), orisha (the Yoruba ritual from western Nigeria, which came to Trinidad), obeah (practised notably by Ashantis in today’s Ghana) and various Bantu influences. Included here are Obeah Man, Alfredo Boy, Chicken Gumbo, Voodoo Woman, Do for Do and two versions of Rookombey. As for Big Confusion, it describes the fight of a Christian pastor against a stickman who resorts to occult practices, as in the line, “The stickman went to the graveyard to dig up some sand” (spirit-powers were attributed to cemetery plots).

Such forms of worship were strongly disapproved of, and often reduced to stereotypes involving seduction, spells and zombies (or “jumbies”), but they remained deeply rooted. In the splendid Obeah Man, for example, Alwyn Richards begs the priest to free him from an unbearable voodoo charm; the style here is closer to traditional quelbe than to calypso. And in Do for Do, singer Lloyd Prince Thomas admits that if his wife is cheating on him, he does exactly the same with the aid of an obeah ritual…

RookombAy

The two magnificent versions of Rookombay included here tell the story of a night-time orisha ceremony in which the Yoruba divinity Shango is evoked:

“One night I took a chance / And I went to a voodoo dance / Oh well I wanted a new romance / That’s why I went to the Shango dance / The High Priest looked very mean / When he appeared upon the scene / And then he made a motion to me / And I began the ceremony / What the chant was / Rookoombey rookoombay Zelma / There was an old lady / She was living in a tomb with ten zombies / She had a calabash in her hand pouring snake oil / On the voodoo man.”

The song goes on to say that a High Priestess named Naomi “didn’t have a hair on her head” and “looked like Boris Karloff in ‘The Walking Dead’,” [the 1936 film directed by Michael Curtiz]. Rookombay was penned by Irving Burgie under a pseudonym. Burgie was a calypso musician born in New York, where he went under the name of Lord Burgess; his father came from Virginia and his mother from the British Commonwealth island of Barbados. Burgess specialized incover-versions of traditional Caribbean songs unearthed playing with island musicians. He then modified their lyrics to make them suitable for American audiences — and signed the songs as his own compositions. He made a fortune by being the first to copyright many such melodies, notably co-signing Day O and Jamaica Farewell, two enormous hits for RCA by his associate Harry Belafonte. Incidentally, it was Belafonte’s Day O producer Herman Diaz Jr. who was behind the Mighty Zebra album (also for RCA) from which some of the best songs here are taken. Chicken Gumbo, like Rookombay, also has voodoo allusions. These two titles were also recorded by the divine Josephine Premice, a New Yorker originally from Haiti.12 Voodoo and obeah spread throughout the Caribbean after they arrived from Africa, going much farther than Louisiana and Haiti as was originally supposed. The twin religions are present throughout the Americas in various forms and under different names. 12

The Fabulous McClevertys

Originally from St. Croix like Bill LaMotta, The Fabulous McClevertys released an album on Verve in 1957. Founded in California by Norman Granz in 1956, the excellent Verve label specialized in jazz; when it was sold to MGM by Granz in 1961, the label turned to more unexpected, if not experimental, music such as the recordings of The Mothers of Invention and The Velvet Underground. The McClevertys’ titles here were enough for these remarkable calypso musicians to enter the history books in their own right, but they are mostly remembered for accompanying (until 1955) the American calypso singer known to record-buyers as The Charmer, whose mother came from St. Kitts and Nevis (his father was Jamaican). In 1955 The Charmer decided to devote his life to the church: the leader of The Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, considered music to be a contradiction of Islamic principles, and several years later, The Charmer replaced him as the movement’s leader… under the name Louis Farrakhan. You can read more of that story and hear The Charmer (accompanied by saxophonist Johnny McCleverty and his Calypso Boys) in our Trinidad anthology.2 But the anecdote has the merit of showing that 1955 was a pivotal period for Afro-American freedom; some were seeking their African roots through Islam, others in the Rastafari movement which was developing in Jamaica, and still others in various Protestant temples, Catholic churches and Revivalist religions.13

THE LaMotta BROTHERS

The hotels in Charlotte Amalie on St. Thomas may have been full, but rare were the holidaymakers who dared to take a boat as far as St. Croix, which lay isolated some 25 miles to the south. History hasn’t always remembered the careers of the more distant (and lesser-known) calypso artists, all of whom were trying to make a living from their music in a difficult, isolated context, and striving to develop the economy of their neglected islands. They had few resources, but one artist at least succeeded as both a businessman and a musician: Bill LaMotta. His career throws light on the realities of calypso music in the Virgin Islands of the Fifties.

Wilbur “Bill” LaMotta was born on January 13th 1919 (he died in 1980) in the little town of Christiansted on St. Croix, the former capital of the Danish Antilles. Born into a family of musicians (Wesley and Elisa de la Motta), young Wilbur showed a precocious talent for music: by the age of five he had a passion for the organ and the clarinet, and he quickly mastered both instruments, playing in the island’s religious ceremonies. In 1936 his composition Heading for Home was published in New York and recorded by several artists. It was the beginning of a prolific career as a composer in which he wrote some 400 titles. His Caribbean identity surfaced in many of them, including The Last Bamboula, Dawn from a Window, In Paradise, Come Back to the Virgin Islands and Bolero for Don Pablo, which was dedicated to cellist Pablo Casals. After going to the Juilliard School of Music in New York, “Bill” LaMotta played all over America with the group he formed with his five brothers—Orville, Lawrence, Raymond, Reuben and John—leaving out their sisters Dorothy and Isabelle. Appearances on radio and television followed, and in around 1940 they are said to have recorded several titles for RCA Victor which contributed to spread the sound of the Caribbean. After studying as a military engineer with the U.S. Navy, Bill LaMotta composed the march King’s Point Victory which became the official anthem of the Merchant Navy. He became an electrician and then was made an Officer in the Merchant Navy during the war. He later spent much time spent on the continent working on several projects, some of them musical. In 1956 he composed a series of titles for trumpeter Bill Fleming, who recorded them (with the LaMotta Brothers) in New York. The group accompanied Mighty Zebra a few days later at RCA’s studios. On his return to The Virgin Islands in 1959, Bill LaMotta became a music-publisher and founded the Westindy Music Corporation together with three Music Man stores where his son Leroy worked (his wife Joyce Anduze ran the Guitar Lady boutique).

An educated man who was also a prominent figure in the islands’ economy, Bill LaMotta the musician slowly turned to a more political career; as a businessman he took charge of the islands’ problematic water and electricity supplies, became a consultant in artistic matters, and took on other responsibilities. As a conservative, he was very direct, and frankly expressed his views in his struggle to bring the region to full bloom. He received several awards for his accomplishments in commerce and the arts, and was in charge of the St. Croix/St. John Chamber of Commerce until his death. He was even posthumously decorated by the Merchant Navy.

Bruno Blum

English adaptation: Martin Davies

Thanks to Fabrice Uriac.

© Frémeaux & Associés

1. Cf. both volumes of Biguine, valse et mazurka créoles (1929-1940 et 1930-1943).

2. Cf. the booklet (also online at fremeaux.com) and album Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5374).

3. Idem Harry Belafonte Calypso-Mento-Folk 1954-1957 (FA 5234).

4. Idem the volume Calypso (FA 5342) in the Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde series.

5. Cf. Bahamas - Goombay & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA 5302).

6. Cf. Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275).

7. Cf. Bermuda - Gombey & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA 5374).

8. Cf. Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine, volumes 1954-1956 and 1956-1958.

9. Cf. Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA 5374); the booklet is also online at fremeaux.com.

10. Cf. The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 and 1960-1962 (FA 5376 etc.).

11. Cf. the future release in this series, Santo Domingo - Merengue.

12. Cf. Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA 5375); the booklet is also online at fremeaux.com.

13. Cf. Jamaica - Trance - Possession - Folk 1939-1961 (FA 5384); the booklet is also online at fremeaux.com.

Disc 1

1. RookombAy - Lloyd Prince Thomas and the Calypso Troubadours (Irving Burgie aka A. Irving, C. Irving)

Lloyd Thomas as Lloyd Prince Thomas-v; backed by The Calypso Troubadours. Musicians unknown. Que Records FLS 101, possibly New York, circa 1956.

2. Obeah Man - Alwyn Richards and the St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra (Alwyn Richards)

Alwyn Richards-v; backed by the St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra. Musicians unknown. Monogram 844. Virgin Islands, circa 1960.

3. Alfredo Boy - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders (Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

William Fleming as Bill Fleming-v; Raymond La Motta-p; Johnny La Motta-g; Ruben La Motta-vb; possibly Fernando Francis-b; possibly Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond La Motta. Produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, October 1, 2 or 3, 1956.

4. Virgin Isle Country Dance - Archie Thomas and his St. Croix Orchestra (Archibald Thomas aka Archie Thomas)

Archibald Thomas as Archie Thomas-v; backed by the St. Croix Orchestra. Musicians unknown. Monogram 844. Virgin Islands, circa 1960.

5. Climbing the Mountain - Lloyd Prince Thomas and the Calypso Troubadours (Lloyd Thomas)

Lloyd Thomas as Lloyd Prince Thomas-v; backed by The Calypso Troubadours. Musicians unknown. Que Records FLS 101, possibly New York, circa 1957.

6. Yo’ Got to Know What to Do - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders (Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

William Fleming as Bill Fleming-v; Raymond La Motta-p; Johnny La Motta-g; Ruben La Motta-vb; possibly Fernando Francis-b, possibly Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond La Motta. Produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, October 1, 2 or 3, 1956.

7. Cash, Cash Me Ball - Alwyn Richards and the St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra

Alwyn Richards-v; backed by the St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra. Musicians unknown. Virgin Islands, circa 1960.

8. Hindu Calypso - Lloyd Prince Thomas and the Calypso Troubadours (Lloyd Thomas)

Lloyd Thomas as Lloyd Prince Thomas-v; backed by The Calypso Troubadours. Musicians unknown. Que Records, possibly New York, circa 1957.

9. One Gone - unknown (unknown)

Unknown-v; musicians unknown. Produced by R.C. Spencely. Virgin Island Calypsos (10”) VLP 400, circa 1957. St. Thomas, Virgin Islands circa 1956.

10. Money Honey - The Fabulous McClevertys (Civial)

Carl McCleverty-v; Johnny McCleverty-as; Gus McCleverty-g; Cornelius McCleverty-p; unknown-b; David McCleverty-d; various McCleverty-backing vocals. Verve MGV-2034. Issued in February 1957.

11. Nazalin and her Mandolin - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders

(Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

William Fleming as Bill Fleming-v; Raymond La Motta-p; John La Motta-g; Reuben La Motta-vb; possibly Fernando Francis-b; possibly Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond

La Motta. Produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, October 1, 2 or 3, 1956.

12. Tease ‘Em Squeeze ‘Em - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders (Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

Same as above.

13. The Ping Pong - The Mighty Zebra W/ The La Motta Brothers Virgin Isles Orchestra (Charles Harris aka The Mighty Zebra)

Charles Harris as The Mighty Zebra-v; unknown sax; Raymond La Motta-p; John La Motta-g; Reuben La Motta-vb; Fernando Francis-b; Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond La Motta. Possibly produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, circa November, 1956.

14. Scandal in St. Thomas - The Mighty Zebra W/ The La Motta Brothers Virgin Isles Orchestra

(Charles Harris aka The Mighty Zebra)

Same as above.

15. How Yo’ Know What I Got - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders

(Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

William Fleming as Bill Fleming-v; Raymond La Motta-p; John La Motta-g; Reuben La Motta-vb; possibly Fernando Francis-b; possibly Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond

La Motta. Produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, October 1, 2 or 3, 1956.

16. Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders (William La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

William Fleming as Bill Fleming-v; Raymond La Motta-p; John La Motta-g; Reuben La Motta-vb; possibly Fernando Francis-b; possibly Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond

La Motta. Produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, October 1, 2 or 3, 1956.

17. Pan Bush Mary - Archie Thomas and his St. Croix Orchestra (Archibald Thomas aka Archie Thomas)

Archibald Thomas as Archie Thomas-v; backed by the St. Croix Orchestra. Musicians unknown. Monogram 844. Virgin Islands, circa 1960.

18. Parakeets - The Fabulous McClevertys (Manny Warner)

Carl McCleverty-v; Johnny McCleverty-as; Gus McCleverty-g; Cornelius MccLeverty-p; unknown-b; David McCleverty-d. Verve MGV-2034. Issued in February 1957.

19. Scratch, Scratch my Back - Lloyd Prince Thomas and the Calypso Troubadours (Lloyd Thomas)

Lloyd Thomas as Lloyd Prince Thomas-v; backed by The Calypso Troubadours. Musicians unknown. Que Records FLS 101, possibly New York, circa 1957.

20. Big Confusion - Lloyd Prince Thomas and the Calypso Troubadours (Lloyd Thomas)

Same as above.

21. West End Romance - Archie Thomas and his St. Croix Orchestra (Archibald Thomas aka Archie Thomas)

Archibald Thomas as Archie Thomas-v; backed by the St. Croix Orchestra. Musicians unknown. Monogram 844. Virgin Islands, circa 1960.

22. Touch It - unknown (unknown)

Unknown-v; musicians unknown. Produced by R.C. Spencely. Virgin Island Calypsos (10”) VLP 400, circa 1957. St. Thomas, Virgin Islands circa 1956.

Disc 2

1. Rookombay - The Fabulous McClevertys

(Irving Burgie aka A. Irving, C. Irving)

Carl McCleverty-v; Johnny McCleverty-as; Gus McCleverty-g; Cornelius McCleverty-p; unknown-b; David McCleverty-d; various McCleverty-backing vocals. Verve MGV-2034. Issued in February 1957.

2. Chicken Gumbo - The Fabulous McClevertys

(Merrick, Willoughby)

Carl McCleverty-v; Johnny McCleverty-as; Gus McCleverty-g; Cornelius McCleverty-p; unknown-b; David McCleverty-d; various McCleverty-backing vocals. Verve MGV-2034. Issued in February 1957.

3. Voodoo Woman - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders

(Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

William Fleming as Bill Fleming-v; Raymond La Motta-p; John La Motta-g; Reuben La Motta-vb; possibly Fernando Francis-b; possibly Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond La Motta. Possibly produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, October 1, 2 or 3, 1956.

4. Englishman’s Diplomacy - The Mighty Zebra W/ The La Motta Brothers Virgin Isles Orchestra

(Charles Harris aka The Mighty Zebra)

Charles Harris as The Mighty Zebra-v; Bill Fleming-tp; unknown sax; Raymond La Motta-p; John La Motta-g; Reuben La Motta-vb; Fernando Francis-b; Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond La Motta. Possibly produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, circa November, 1956.

5. We Like Ike - The Mighty Zebra W/ The La Motta Brothers Virgin Isles Orchestra

(Charles Harris aka The Mighty Zebra)

Same as above.

6. Breakfast in a Flying Saucer - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders

(Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

William Fleming as Bill Fleming-v; Raymond La Motta-p; John La Motta-g; Reuben La Motta-vb; possibly Fernando Francis-b; possibly Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond

La Motta. Produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, October 1, 2 or 3, 1956.

7. Vim Vigor and Vitality - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders

(Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

Same as above.

8. Creole Gal - The Duke of Iron

(Cecil Anderson aka Duke of Iron)

Cecil Anderson as The Duke of Iron-v; musicians unknown. Produced by R.C. Spencely. Virgin Island Calypsos (10”) VLP 400, circa 1957. St. Thomas, Virgin Islands circa 1957.

9. Foolish Man - Lloyd Prince Thomas and the Calypso Troubadours

(Lloyd Thomas)

Lloyd Thomas as Lloyd Prince Thomas-v; backed by The Calypso Troubadours. Musicians unknown. Que Records, possibly New York, circa 1957.

10. Brown Skin Girl - Lloyd Prince Thomas

Same as above.

11. Hit and Run - Alwyn Richards and the St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra

Alwyn Richards-v; backed by the St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra. Musicians unknown. Virgin Islands, circa 1960.

12. Kum to Papie - Alwyn Richards and the St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra

Alwyn Richards-v; backed by the St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra. Musicians unknown. Virgin Islands, circa 1960.

13. I Went to College - The Mighty Zebra W/ The La Motta Brothers Virgin Isles Orchestra

(Charles Harris aka The Mighty Zebra)

Charles Harris as The Mighty Zebra-v; Bill Fleming-tp; unknown sax; Raymond La Motta-p; John La Motta-g; Reuben La Motta-vb; Fernando Francis-b; Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond La Motta. Possibly produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, circa November, 1956.

14. The Female Woodcutter - The Mighty Zebra W/ The La Motta Brothers Virgin Isles Orchestra

Same as above.

15. Do for Do - Lloyd Prince Thomas and the Calypso Troubadours

(Lloyd Thomas)

Lloyd Thomas as Lloyd Prince Thomas-v; backed by The Calypso Troubadours. Musicians unknown. Que Records FLS 101, possibly New York, circa 1957.

16. Moco Joe - Lloyd Prince Thomas and the Calypso Troubadours

(Lloyd Thomas)

Same as above.

17. Tickle, Tickle - The Fabulous McClevertys

(Manning)

Carl McCleverty-v; Johnny McCleverty-as; Gus McCleverty-g; Cornelius McCleverty-p; unknown-b; David McCleverty-d; various McCleverty-backing vocals. Verve MGV-2034. Issued in February 1957.

18. Don’t Blame It on Elvis - The Fabulous McClevertys

(Manning)

Carl McCleverty-v; Johnny McCleverty-as; Gus McCleverty-g; Cornelius McCleverty-p; unknown-b; David McCleverty-d; various McCleverty-backing vocals. Verve MGV-2034. Issued in February 1957.

19. Watch Calla from Guatemala - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders

(Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

William Fleming as Bill Fleming-v; Raymond La Motta-p; John La Motta-g; Reuben La Motta-vb; possibly Fernando Francis-b; possibly Paul Moron-d. Arranged by Raymond

La Motta. Produced by Herman Diaz, Jr. Vik LX-1079. RCA studio 2, New York City, October 1, 2 or 3, 1956.

20. Stop the Boat - Bill Fleming W/ The La Motta Brothers and the Virgin Islanders

(Wilbur La Motta aka Bill La Motta)

Same as above.

21. Coldest Woman - The Fabulous McClevertys

(Warner)

Carl McCleverty-v; Johnny McCleverty-as; Gus McCleverty-g; Cornelius McCleverty-p; unknown-b; David McCleverty-d; various McCleverty-backing vocals. Verve MGV-2034. Issued in February 1957.

22. Palma Dumplin’ - Archie Thomas and his St. Croix Orchestra

(Archibald Thomas aka Archie Thomas)

Archibald Thomas as Archie Thomas-v; backed by the St. Croix Orchestra. Musicians unknown. Monogram 844. Virgin Islands, circa 1960.

23. Kill Thing Pappy - Archie Thomas

(Archibald Thomas aka Archie Thomas)

Same as above.