- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

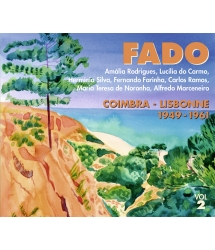

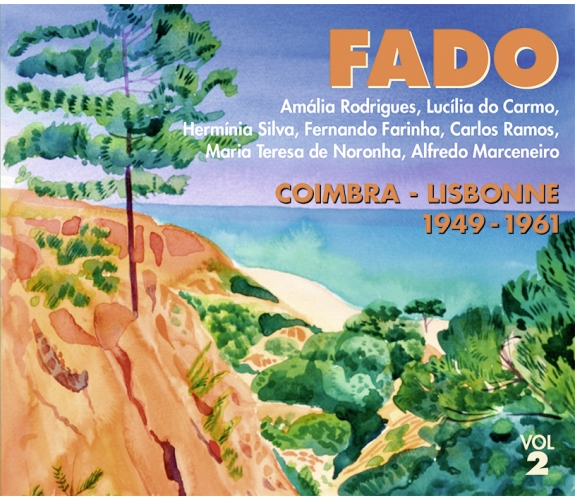

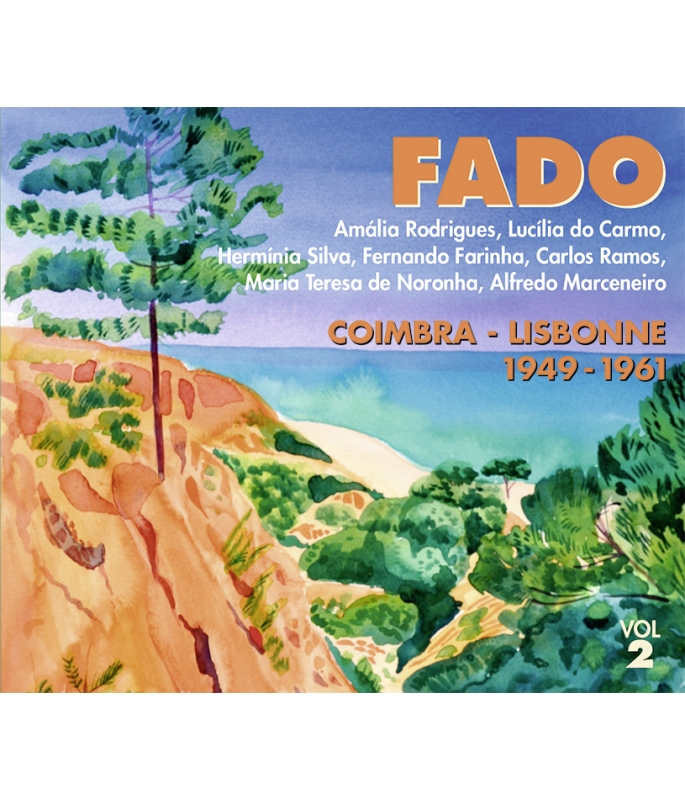

COIMBRA - LISBONNE (1949 - 1961)

Ref.: FA5399

EAN : 3561302539928

Direction Artistique : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 1 heures 49 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

COIMBRA - LISBONNE (1949 - 1961)

Né à Lisbonne, capitale portuaire qui fut le point d’ancrage et de métissage de cultures venues de l’au-delà des océans (Brésil, Açores, Afrique...) et des provinces rurales du Portugal, le fado est un genre musical populaire authentique plus que centenaire.

Il est porté, dans notre anthologie qui couvre les belles années cinquante, par Amália Rodrigues, son héroïne principale, par la figure mythique d’Alfredo Marceneiro, par la voix splendide de Carlos Ramos ainsi que par les artistes de l’autre branche du Fado, celui de Coimbra.

Fado is an authentic music-genre more than a hundred years old, and it was born in Lisbon, the capital famous as the seaport where a mixture of cultures came to anchor after crossing the oceans separating the Azores from Brazil and Africa.

In this anthology, which spans the Fifties, the beautiful sounds of Fado are carried by the voices of the genre’s principal heroine, Amália Rodrigues, the legendary Alfredo Marceneiro and the splendid singer Carlos Ramos, together with artists representing the other face of Fado, the Coimbra style.

Droits : Frémeaux & Associés / DP

CD1 :

ADEUS MOURARIA (CARLOS RAMOS) • SENHORA DO MONTE (ALFREDO MARCENEIRO) • VIELAS DA ALFAMA (CARLOS RAMOS) • BAIRROS DE LISBOA (A. MARCENEIRO, MARIA FERNANDA) • FOI NA TRAVESSA DA PALHA (LUCÍLIA DO CARMO) • A NOVA TENDINHA (HERMÍIA SILVA) • BALADA DE COIMBRA (COIMBRA QUINTET) • EU JA NÃO SEI (CARLOS RAMOS) • FADO RIBATEJANO (HERMÍNIA SILVA) • FADO HILARIO (AMÁLIA RODRIGUES) • CANÇÃO DE LISBOA (FERNANDO FARINHA) • FADO TRISTE (COIMBRA QUINTET) • MOURARIA (MARIA TERESA DE NORONHA) • VARIAÇÕES EM RÉ MENOR (COIMBRA QUINTET) • OLHOS GAROTOS (LUCÍLIA DO CARMO) • MINHA FREGUESIA (ALFREDO MARCENEIRO) • BELOS TEMPOS (FERNANDO FARINHA) • COIMBRA (AMÁLIA RODRIGUES).

CD2 :

MEU DESEJO (COIMBRA QUINTET) • VEIO A SAUDADE (CARLOS RAMOS) • A CASA DA MARIQUINHAS (ALFREDO MARCENEIRO) • LISBOA ANTIGA (HERMÍNIA SILVA) • SEMPRE QUE LISBOA CANTA (CARLOS RAMOS) • RAPSODIA DE FADOS (LUCÍLIA DO CARMO) • BEIJO EMPRESTADO (FERNANDO FARINHA) • MOCITA DOS CARACOIS (ALFREDO MARCENEIRO) • TOADA BEIRA (COIMBRA QUITET) • ALEXANDRINO (MARIA TEREZA DE NORONHA) • FADO PRIM PRIM (HERMÍNIA SILVA) • SERRA D’ARGA (COIMBRA QUINTET) • MARIA DA GRAÇA (CARLOS RAMOS) • FADO DA SAUDADE (AMÁLIA RODRIGUES) • MATARAM A MOURARIA (M. T. DE NORONHA) • PODEMOS SER AMIGOS (LUCÍLIA DO CARMO) • AQUARELA PORTUGUESA (COIMBRA QUINTET) • O CHICO DO CACHENÉ (FERNANDO FARINHA) • FADO DO ESTUDANTE (COIMBRA QUINTET).

A COUNTRY’S SOUL / A ALMA DO PAÍS

LISBOA - COIMBRA 1926-1941

ANTHOLOGIE 1950 - 1999

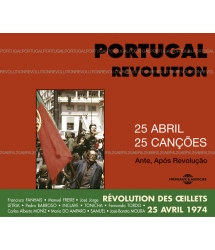

REVOLUTION DES OEILLETS 25 AVRIL 1974

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Adeus MourariaCarlos RamosArtur Ribeiro00:03:081958

-

2Senhora Do MonteAlfredo MarceneiroGabriel De Oliveira00:02:541961

-

3Vielas Da AlfamaCarvalhinhoArtur Ribeiro00:03:281958

-

4Bairros De LisboaAlfredo MarceneiroCarlos Conde00:03:321960

-

5Foi A Travessa Da PalhaFrancisco CarvalinhoGabriel De Oliveira00:02:431958

-

6A Nova TendhinaHerminia SilvaCarlos Lopes00:02:281958

-

7Balada De CoimbraCoimbra QuartetJ. Elyseu00:02:331957

-

8Eu Ja Nao SeiCarlos RamosAloisio Augusto Da Costa00:03:201961

-

9Fado RibatejanoHerminia SilvaInconnu00:02:381958

-

10Fado HilarioAmalia RodriguezAugusto Hilario00:02:381958

-

11Cancao De LisboaFernando FarinhaFernando Farinha00:02:361958

-

12Fado TristeCoimbra QuintetDr F. Menano00:02:541957

-

13MourabiaMaria Teresa De NoronhaMaria Helena Guerreiro00:02:381961

-

14Variacoes Em Re MenorCoimbra QuintetAlberto Santos Dumont00:04:021961

-

15Olhos GarotosLucilia Do CarmoJaime Santos00:02:011958

-

16A Minha FreguesiaRaul NeryArmando Neves00:02:081962

-

17Belos TemposFernando FarinhaFernando Farinha00:04:051960

-

18CoimbraAmalia RodriguezJose Galhardo00:02:231957

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Mi DeseoCoimbra QuintetMeu Desejo00:03:101957

-

2Veio A SaudadeCarlos RamosArtur Ribeiro00:03:321958

-

3A Casa Da MariquinhasAlfredo MarceneiroSilva Tavares00:04:081961

-

4Lisboa AntigaSilva HerminiaAmadeu Do Vale00:02:431958

-

5Sempre Que Lisboa CantaCarlos RamosCarlos Rocha00:02:341957

-

6Rapsodia De FadosLucilia Do CarmoLinhares Barbosa00:03:171958

-

7Beijo EmprestadoFernando FarinhaFernando Farinha00:02:431960

-

8Mocita Dos CaracoisAlfredo MarceneiroAlfredo Duarte00:03:261961

-

9Toada BeiraCoimbra QuintetLuis Goes00:03:101957

-

10AlexandrinoMaria Teresa De NoronhaFreire00:02:311961

-

11Fado Prim PrimCoimbra QuintetFederico Valerio00:02:321957

-

12Serra D'ArgaCoimbra QuintetM. Soares00:02:091957

-

13Maria Da GracaCarlos RamosArtur Ribeiro00:03:011958

-

14Fado Da SaudadeAmalia RodriguezF. De Freitas00:03:131952

-

15Mataram A MourariaMaria Teresa De NoronhaMaria Teresa De Noronha00:02:401961

-

16Podemos Ser AmigosJaime SantosMaria Teresa De Noronha00:03:251958

-

17Aquarela PortuguesaCoimbra QuintetA. Portugal00:02:481961

-

18O Chico Do CacheneFernando FarinhaLinhares Barbosa00:02:521960

-

19Fado Do EstudanteCoimbra QuintetM. Soares00:03:031957

Fado FA5399

FADO

Amália Rodrigues, Lucília do Carmo, Hermínia Silva, Fernando Farinha, Carlos Ramos, Maria Teresa de Noronha, Alfredo Marceneiro

Coimbra - lisbonne

1949 - 1961

Vol 2

LE FADO (1949 - 1961)

« Fado é destino marcado

Fado é perdão ou castigo

A propria vida é um fado

Que o coração traz consigo »

« Le Fado est le destin tracé / le Fado est pardon ou châtiment / La vie elle-même est un fado / que le cœur porte en soi » (Alcindo de Carvalho)

Fado au Teatro São Luiz

Quelle ferveur en cette nuit du 25 mai 1963, au Teatro São Luiz de Lisbonne, ferveur que le disque A Noite do Fado nous restitue : elle signe les adieux à la scène d’Alfredo Marceneiro dont les premières apparitions publiques datent de 1910 et qui s’est professionnalisé dès 1928. Toutes les grandes voix sont là pour rendre hommage à cette figure tutélaire du milieu fadiste : Hermínia Silva, Lucília do Carmo, Fernanda Maria, Fernando Farinha, Maria Teresa de Noronha. Ne man-que à l’appel qu’Amália Rodrigues, sans doute en tournée à l’étranger (sur le thème Fado Bailado d’Alfredo Marceneiro, elle avait posé, pour la première fois de sa vie, dans les années cinquante, des paroles pour une chanson qui sera intitulée Estranha forma de vida). Que ressent-on à l’écoute de ce disque qu’on ne peut inclure dans notre anthologie pour des raisons légales ? Le regret immense de ne pas avoir partagé in situ la vibration du public, le grain particulier de chaque voix, des modulations et des ornements qui font la singularité d’un artiste et la présence magique voisine d’une stature mythique d’Alfredo Marceneiro. Même sans comprendre la langue portugaise, on perçoit qu’il y a là une voix qui porte le chant profond et la noblesse communautaire des quartiers populaires de Lisbonne. Nous sommes en 1963, il reste encore onze ans de dictature fascisante à vivre, et malgré les réticences morales de l’Estado Novo à son égard, le fado est toujours populaire dans les deux acceptions du terme : il parle toujours aux couches populaires et il est un genre suffisamment à la mode pour que les compagnies discographiques investissent sur lui. D’une certaine manière, ces années cinquante et soixante marquent l’apogée du fado, bien enregistré, bien divulgué par la presse et la radio pour ne plus apparaitre comme étant seulement la musique de Lisbonne mais bien plus largement comme l’expression de l’âme portugaise.

L’histoire du fado

Le fado (l’origine du mot est latine = Fatum ; soit le destin) émerge en une lente et longue maturation, sur près d’un siècle et demi, d’abord comme une spécificité de la vie urbaine de Lisbonne avant de s’identifier comme musique nationale portugaise. Son essor est inextricablement lié à l’histoire culturelle, politique, sociale et économique du pays (passage de la royauté à la république laïque et, de 1928 à 1974, à la dictature de l’Estado Novo) et un des marqueurs de son identité sonore, au Portugal même ou à l’étranger, est le son plaintif si particulier de la « guitarra portuguesa » (12 cordes métalliques, 17 frettes qui couvrent trois octaves et demies), une forme évoluée du luth et de la guitare dite anglaise du 18e siècle. Pour comprendre comment, dans une forme de balancier, ses valeurs passent, au fil des décades, des idéaux de la gauche prolétarienne au conservatisme, de la lutte pour un destin meilleur à la soumission au fatalisme, il est utile de brosser les grandes phases historiques sans revenir sur la querelle des sources et influences qui auraient permis son éclosion (l’influence mauresque, brésilienne, celle des modes des grandes capitales comme Londres, Vienne ou Paris) parce qu’elles sont finalement assez sujettes à caution. En synthèse, le fado est un genre populaire urbain né dans la ville portuaire qu’est Lisbonne, ville ouverte au métissage des cultures venues d’ailleurs mais aussi capitale qui a toujours été un point de convergence pour les provinciaux des régions reculées et pauvres du Portugal. Il suffit de relever que le père de Severa, la première fadiste reconnue, était originaire de Santarem, qu’Amalia Rodrigues a toujours reconnu l’influence exercée sur elle par les berceuses que lui chantait sa mère venue de Beira Baixa, une région jouxtant l’Espagne et que le père d’Alfredo Marceneiro était de Cadaval.

Au cours de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle, le lundum (danse afro-brésilienne) et la modinha (chanson romantique), genres brésiliens en vogue à l’époque, s’effacent pour laisser place à un genre plus lusitanien qui n’est pas dansant où le chant se mêle au fond musical et qui, assez vite, sort du milieu des gargotes et des bordels pour s’épanouir dans les quartiers populaires où l’aristocratie bohême viendra s’encanailler. Comme au Brésil dans le monde des sambistes, on commence à qualifier les chanteurs par leur profession ou par un de leur trait spécifique ; ainsi ou trouve Chico Torneiro (plombier), Antonio da Praça (de la place) Epifanio Mulato ou Jorge Sapateiro (cordonnier)… Le plus renommé de nos jours demeurant Alfredo Marceneiro (ébéniste). Avec les mouvements associatifs qui favorisent l’alphabétisation, au temps de la république, le fado prend des couleurs sociales et anticléricales avant que le conservatisme moralisateur de L’Estado Novo de Salazar ne cherche à éteindre la flamme. Puis, peu à peu, l’identité du « fadiste » change : il n’est pas rétribué pour chanter mais il est invité à se produire dans les salons où il reçoit des cadeaux de valeur. Ce sera le premier pas vers la professionnalisation complète qui sera la règle des années trente, sous l’impulsion des comédies musicales et du disque 78 T mais qui est aussi imposé par une directive en droit du travail de la dictature. Ces années trente sont aussi marquées par l’apparition d’un nouveau style d’établissement : les « casas de fado » (les maisons du fado) ouvertes à une clientèle moins populaire et plus sélecte mais néanmoins amatrice du genre et l’on raconte que certains intellectuels y faisaient de virées nocturnes C’est l’époque d’artistes d’envergure comme les chanteuses Ercília Costa, Berta Cardoso, Maria Alice ou du guitariste et compositeur Armandinho. Certes, avec la professionnalisation, on perd le sel de l’improvisation poétique et musicale pour s’enfermer dans un espace plus ritualisé bien qu’on y perpétue les fados « castiços » (purs). Sous l’emprise de la censure, les textes du répertoire se figent sur certaines thématiques pleines de pathos loin de la sensibilité sociale d’antan et les performances ont tendance à s’enfermer dans les 3 minutes imposées par les enregistrements des 78 T. Il n’en existe pas moins une extraordinaire vitalité artistique favorable à l’émulation et à la créativité : l’artiste sera jugé par l’auditoire sur sa capacité à donner des versions enflammées et personnalisées (ornementations libres sur une note suspendue, par exemple ; osmose entre voix et cordes, improvisation de la « guitarra » à certains moments clés). Les artistes les plus reconnus des ces années quarante et cinquante sont ceux que l’on retrouve dans notre anthologie. A l’écoute de Carlos Ramos et d’Alfredo Marceneiro, on vérifiera que, dans un même moule et pour une finalité identique, deux esthétiques s’imposent et s’opposent et qu’il est bien difficile de donner une préférence. Chaque fois que le fado connaitra des évolutions, il y aura des gens pour dire qu’il perd de sa pureté mais cela ne change rien au mouvement de balancier idéologique qui perdurera jusqu’à la fin des années soixante dix : d’un côté, la gauche prolétarienne qui déteste le fatalisme du fado et son acceptation des conditions politiques et sociales et, de l’autre, la droite conservatrice qui reproche au fado son immoralité, son manque de respectabilité sociale et son éloignement des thématiques rurales des chorales paysannes.

De quelques règles esthétiques

Tout bon interprète du fado se doit de répondre à certains critères pour être reconnu par ses pairs et par un public averti. Certains relèvent de l’évidence, d’autres sont plus spécifiques au genre du fado lisboète qui est un chant populaire né dans la rue. Un peu à l’image de ce qui se fait dans le jazz, l’interprète doit chanter juste et avoir la notion du phrasé - on devrait ne pas avoir à souligner cela - mais avant tout, il lui faut savoir affirmer une personnalité (en portugais, on dit « estilar », soit, pour mieux expliquer, faire varier la ligne mélodique de strophe en strophe en introduisant des éléments d’ornementation improvisés) par son expressivité, par ses capacités d’ornementation et d’association des mots (en portugais, la formule est « dividir »), bref, il est impératif d’accentuer et de respirer selon les codes propres au fado pour mettre en avant les paroles puisque le fado serait, selon certains, avant tout une danse des paroles. Alfredo Marceneiro ne disait-il pas : « Ce n’est pas la voix qui compte le plus dans le fado, c’est avant tout de bien savoir dire les mots et diviser les vers, les accentuer avec intentionnalité ». Mais, contrairement au flamenco, le chant fadiste est austère, en une expressivité contenue, et une posture gestuelle presque en totale immobilité. Ce serait Alfredo Marceneiro qui aurait lancé le fait de chanter debout, une main dans une poche et Amalia Rodrigues celui de se planter devant les musiciens. En scène, le fado impose l’entendimento, qui fournit le support harmonique et rythmique. C’est dans le prélude instrumental, parfois assez long dans les prestations publiques, que les cordes donnent le tempo général du chant sur lequel la voix du fadiste va jongler avec les mesures. Autre code : la dernière reprise du refrain ou de la dernière strophe est toujours annoncée par la voix qui prend une allure trainante, le final s’achevant sur un crescendo renforcé par les accords forte des guitares, final souligné par les mains du chanteur pour fixer l’emphase mélodramatique. Même si toute écoute privilégie, souvent inconsciemment, la musicalité de la voix, il est recommandé de bien l’appréhender au sein de la dynamique souvent hallucinante des cordes (le « Conjunto de guitarras : deux « guitarras », une « viola » et une « viola baixo » de Raul Nery était un modèle du genre).

Comme il s’agit d’une musique populaire, le fado a évolué du plus simple au plus complexe. Les « fados castiços », les plus anciens - les plus purs au dire des tradtionnalistes - sont le fado corrido en ré, le fado menor en mi et le fado mouraria en sol. Ces fados servent à conter une histoire avec un début, un milieu et une fin au long d’un nombre indéfini de « quadras » (couplets). Les différences entre fado Corrido et fado Mouraria tiennent à des introductions propres à chacun et à une différenciation d’accentuation qui aura un impact sur la manière de « filer » le chant. Ensuite, dans l’évolution du genre, sont apparus les fados avec deux tonalités (4 accords, positions différentes des doigts sur les cordes, alternance entre ton majeur et son relatif en mineur, mélodie plus élaborée qui donne un champ plus large pour les variations) puis viendra, né avec les revues musicales, le fado-canção qu’on dit plus subtil mélodiquement et harmoniquement et qui se divise comme dans une chanson classique en couplets et refrain mais qui oblitère toute improvisation contrairement au fado « authentique » (castiço).

Le Fado de Coimbra

Dès le 17e siècle, son université avait un grand renom en Europe (la fabuleuse bibliothèque qui se visite impose une sérénité silencieuse) et Coimbra reste une ville magique, quoique un peu assoupie sous le soleil en été, qui coule des jours paisibles de long du Mondego. Lorsque l’on aborde le thème du fado, il est de coutume d’opposer le fado de Lisbonne, qui serait plus bohème (« vadio » disent les portugais) et populaire, à celui de Coimbra plus érudit et romantique ; certains allant même jusqu’à affirmer qu’il serait plus juste de parler de « chanson de Coimbra » que de fado. Et, de fait, il suffit de poser sur une platine un disque de José Afonso ou de Luis Góes pour se convaincre qu’un monde sépare le genre de la ville aux sept collines de celui des rives du Mondego.

A mon sens, dans son livre Ao Fado tudo se canta, Daniel Gouvea tire une excellente synthèse des différences esthétiques. Il relève des points essentiels qui abordent autant la lutherie et les costumes que les paroles, les compositions ou le port de la voix. Il écrit en substance :

• Le fado lisboète a un enracinement populaire (les fadistas, jusque dans les années cinquante, était souvent des semi-analphabètes et certaines des reproductions de manuscrits sur un des murs du Museu do Fado en font foi) alors que celui de Coimbra est issue de l’élite intellectuelle et universitaire du Portugal et de ses ex-colonies.

• Le fado lisboète est d’abord une chanson intimiste et de recueillement alors que celui de Coimbra est plus extraverti comme peut l’être une « serenata », la sérénade qui se donne sous le balcon des jeunes filles.

• Le fado de Lisbonne est créé avant tout par des lisboètes qui, certes, peuvent avoir des racines familiales rurales mais qui s’identifient viscéralement à leur ville alors que celui de Coimbra est crée par des étudiants qui ne sont pas natifs des rives du Mondego mais viennent d’horizons aussi divers que les Açores, Madère ou le Brésil ou de toute autre région du Portugal. (il est vrai que les membres de la famille Paredes, Gonçalo le père, Artur, le fils et Carlos, le petit-fils, tous prodigieux solistes de la « guitarra portuguesa » étaient originaires de Coimbra mais n’en avait jamais fréquenté son université pour être issus d’un milieu modeste).

• Le chant du fado lisboète épouse la langue du quotidien et ses mélodies se plient avec naturel aux textes alors que, à l’instar de toute musique érudite, les paroles des chansons de Coimbra se soumettent à la ligne mélodique.

• A Lisbonne, peu importe, comme dans toutes genres populaires, que la voix, qu’elle soit masculine ou féminine, soit rauque ou voilée et de timbre peu orthodoxe alors que Coimbra emprunte au chant lyrique et valorise des voix masculines souvent de ténor.

• Le look, lui aussi, diffère. A Coimbra, on se couvre de l’uniforme noir des étudiants alors que le lisboète s’habille comme il l’entend, parfois avec une touche dandy comme Alfredo Marceneiro (casquette, foulard de soie, cigarette au bec et main dans la poche ; le châle est l’accessoire des chanteuses mais il est de couleur indifférente et couvre tout type de robe).

• Différences également dans le regard porté sur la gent féminine : dans le fado lisboète, la femme est traitée sur un pied d’égalité alors qu’à Coimbra, un peu à l’image des troubadours et des romantiques, elle est mise sur un piédestal quasi inaccessible.

• Même la lutherie diffère que ce soit dans la manière d’accorder l’instrument, dans les timbres, dans les techniques d’exécution et les dimensions de la caisse de la « guitarra » (celle de Coimbra est plus élancée alors que celle de Lisbonne est plus large que longue). Destinée à accompagner des voix masculines, celle de Coimbra est plus grave et sonne plus austère et le bras de l’instrument est plus long.

Les grandes signatures du Fado de Coimbra

On le comprend à la lecture des paragraphes ci-dessus, les sources historiques du fado de Coimbra sont autres mais il n’en reste pas moins que le fado de Coimbra est enfant naturel du fado de Lisbonne. Celui qui est reconnu comme étant le fondateur de la «serenata » de Coimbra est Augusto Hilário ; quand on emprunte son style, on parle de « fado Hilário » (un étudiant fort bohème né en 1864 et décédé jeune en1896). C’est avec la génération des frères Menano (Francisco, Alberto, Horacio et Antonio) et de leurs amis Almeida d’Eça, Paulo de Sá que l’émancipation, la définition et la consolidation définitive prend forme dans les années trente. On trouve aisément, chez EMI-Valentim de Carvalho, de magnifiques rééditions de 78 T du Doutor Menano. On relèvera aussi les noms de Antonio Portugal et Manuel Morra (guitarras), de Manuel da Costa Braz et Antonio Serrão (violas) et des chanteurs Luis Góes et José Afonso. Artur Paredes, employé de banque qui ira résider à Lisbonne à la fin des années trente, a laissé des monuments de la musique locale (Il faut impérativement écouter ses enregistrements de 1961, avec son fils Carlos et Arménio Silva à la viola, reparu sous forme CD chez Alvorada). Edmundo Bittencourt était aussi, parait-il, un très bon chanteur à la voix cristalline. En 1955, Fernando Machado Soares, assisté d’Antonio Portugal, constitue un groupe avec Jorge Caldeira comme seconde « guitarra », Manuel Pepe et Levy Baptista aux « violas ». Ils enregistreront à Madrid, en 1957, pour Philips, les titres que nous offrons dans notre anthologie en notant toutefois que Machado Soares, souffrant, a été remplacé au dernier moment par Luis Góes. Ce LP, resté dans l’histoire sous le titre de Coimbra Quintet, est le disque représentatif de la musique de Coimbra le plus vendu. Les années 60 se caractériseront, sans rupture brutale avec le passé culturel, par une lutte plus prononcée contre la dictature. Paru en 1969, Flores para Coimbra est chanté par Antonio Bernardino sur des compositions d’Antonio Portugal, Francisco Martins et Luis Filipe. Après la Révolution des Œillets de 1974, les capes et les soutanes (« batinas » en portugais) noires qui passent pour être identifiées aux forces réactionnaires sont abandonnées. Si on souligne que Antonio Menano, né en 1895 et décédé en 1969, était docteur en médecine, que Antonio Brojo, né en 1927, était professeur en pharmacie, que luis Góes, né en 1933, était dentiste comme l’écrivain de Coimbra Miguel Torga, que Antonio Portugal, né en 1931, était juriste et que Machado Soares, né en 1930 aux Açores, était magistrat et proche ami de José Afonso dont les militaires choisiront Grândola Vila Morena pour signal du lancement des opérations de la Révolution des Œillets, on aura une vision claire de la différence sociale de ces artistes avec ceux de Lisbonne.

Auteurs, Compositeurs et instrumentistes

Avant d’en venir aux portraits des chanteurs de notre anthologie, il est impératif de nommer quelques ins-trumentistes de grande valeur sans lesquels le fado n’aurait pas de saveur. Le guitarrista Armandinho (Armando Augusto Freire 1891-1946 ; qui fut l’élève de Petrolino, ce dernier ayant lui-même été l’élève de João-Maria dos Anjos, ce qui démontre bien la valeur des transmissions dans l’évolution du fado) a donné de superbes compositions aux accents rapsodiques ainsi que des enregistrements en soliste qui laissent imaginer ce que devait être ses facultés d’improvisation en public. Raul Néry (né en 1921), qui un temps, alors qu’il n’avait que 18 ans, a tenu la seconde guitarra aux côtés d’Armandinho, fut pendant vingt ans l’accompagnateur d’Amália Rodrigues. En 1959, il a monté son fameux « Conjunto de Guitarras » avec José Fontes Rocha (guitarra), Julio Gomes (viola) et Joel Pina (Viola baixo). Son fils Rui Vieira Nery est un musicologue auteur de deux livres essentiels sur le fado. Jaime Santos (1909-1982) a longtemps joué aux côtés de Martinho d’Assunção, qui lui tenait la viola et était le fils d’un militant socialiste. Compositeur et virtuose réputé, Jaime Santos a laissé de nombreux disques. On pourrait également citer Francisco Carvalinho, Casimiro Rocha et Domingos Camarinha (1915-1993) qui a accompagné Amália Rodrigues de 1954 à 1966.

Certains définissant le fado comme « la danse des paroles », on ne peut oublier de citer des paroliers « populaires » comme Artur Soares Pereira qui était chef du service de manutention de l’hôpital São José et qui refusait qu’on le traite de poète ou Frederico de Brito, chauffeur de taxi, et Linhares Barbosa, tourneur – fraiseur. Ces deux-là étaient constamment sollicités tant leur talent était reconnu. Mais le fado faisait aussi appel à des plumes d’intellectuels comme David Mourrão Ferreira (beau-frère de Valentim de Carvalho, professeur d’université, essayiste et poète reconnu des lettres portugaises, qui fut secrétaire d’Etat à la culture et au premier gouvernement de Mario Soares), João Silva Tavares, Alexandre O’Neill, Luis de Macedo ou Manuel Alegre . Il en allait un peu de même avec les compositeurs. Frederico de Freitas, qui était passé par le conservatoire, a laissé de nombreuses partitions pour des ballets, Frederico Valerio (1913-1982) a écrit pour Amália Rodrigues jusqu’à la fin des années cinquante (Confesso, Fado do Ciume, Sabe-se lá) avant de céder la place au franco-portugais Alain Oulman (1928-1990 ; 22 musiques sur 8 albums d’Amália Rodrigues) qui était de la famille de l’éditeur Calmann - Levy.

Portraits des interprètes

Carlos Ramos

Cet artiste de classe, sobre et pudique en scène comme au disque, trop méconnu en nos terres, offre la plénitude du sentiment fadiste. Né le 10 octobre 1907 et décédé d’une thrombose le 9 novembre 1969, il était né dans une famille modeste d’Alcântara et avait du abandonner ses études de médecine à la mort de son père. Bon guitariste, il joue au Retira de Severa, au Café Luso et au Café Mondego, accompagne Ercília Costa – une des voix majeure du fado – avant de lui-même embrasser tardivement, à près de quarante ans, la carrière de chanteur. Il s’adonne essentiellement au fado-canção qui correspond mieux à sa sensibilité et à son art de « diseur » que le fado traditionnel qui demande plus de talent d’improvisation. Il participe à quelques films, à des émissions de télévision, enregistre près de vingt disques (78t, EP et LP) avant d’ouvrir « A Toca », sa propre « casa de fado » en 1959. Suite à des troubles cardiaques, il doit cesser assez vite son activité artistique. Avec sa voix de velours pas trop plaintive, un sens du phrasé et de la respiration parfait, il est, sans nul doute, un des plus grands chanteurs de l’histoire du fado.

Alfredo Marceneiro

Alfredo Rodrigo Duarte, né en février 1891 à Lisbonne, dans le freguesia de Santa Isabel, y terminera ses jours en juin de 1982 après une vie intense auprès de plusieurs compagnes et cinq enfants. Celui qu’on surnommait « Alfredo Lulu » pour son allure de dandy dans sa jeunesse, restera dans l’histoire sous l’appellation de « Alfredo Marceneiro » et son image (casquette, foulard de soie pour protéger la gorge, cigarette au bec et main dans la poche) est presque devenue l’image d’Epinal du « fadista » du XX° siècle. Issu d’une famille humble, il avait du abandonner l’école primaire à 13 ans à la mort de son père pour subvenir aux besoins de la famille. Il montre très vite des dons d’improvisateur dans la versification des paroles (c’est lui qui aurait introduit les alexandrins dans le fado alors que la règle était celle des décasyllabes) et, dès la fin des années vingt, il est déjà adopté par le milieu fadiste. Il se produit aux côtés d’Armandinho, de Filipe Pinto et de Julio Proença, les figures de proue de l’époque. Après avoir passé, en 1943, quelques temps en prison pour fait de grève (le mouvement ouvrier réclamait des journées de travail de 8 heures) alors qu’il fabriquait, pour le compte d’une entreprise, des meubles pour les navires, il décide d’abandonner toute activité salariée classique pour se professionnaliser comme fadista. Il aimait plus se produire en public, dans toutes les plus fameuses « casas de fado », que d’enregistrer des disques (il confessait avoir l’impression de parler à des machines), ce qui explique une relative courte discographie (4 LP et 3 EP) et tardive (il n’a enregistré que de 1961 à 1963). Autodidacte, il composait d’oreille et c’était ses guitaristes qui relevaient ses improvisations pour les transcrire sur partitions afin qu’il puisse les enregistrer à la société des auteurs. Personnage direct, il était réputé pour ses sautes d’humeur (« tu étais encore dans les couches que je chantais déjà » lance-t’il à un guitariste qui lui reprochait de rater son entrée après l’introduction). Stylistiquement parlant, il partait des fados traditionnels à structure simple et répétitive mais pour les convertir par des procédés compositionnels qui marquent son identité. Sa grande réputation tient plus à son sens de l’énergie et de la scansion qu’à la pureté de son chant et son impact sur l’auditeur est aussi fort et envoutant que celui du sambiste Nelson Cavaquinho. Fernanda Maria est la seule chanteuse à avoir eu le droit de se mesurer à lui dans une « descarraga » (défi improvisé).

Fernando Farinha

(1928-1988). Celui qu’on avait sunommé « O Miúdo da Bica » après qu’il se soit produit, à 9 ans, dans un concours au Bairro da Bica (quartier de Bica), est devenu professionnel, sur dispense, à l’âge de 11 ans après le décès de son père. Chanteur prolifique, un peu imbu de lui comme le sont souvent les chanteurs à voix de ténor, il enregistre son premier disque en 194O mais il a aussi composé pour les autres (Isto é Fado pour Fernanda Maria, O Teu olhar pour Carlos Ramos, Lugar Vazio pour Hermínia Silva). Sa carrière a décliné dans les années soixante.

Hermínia Silva

(1913-1993). Née seulement cinq années après Ercília Costa, elle apporte au fado une dimension moins tragique, une critique sociale assise sur l’humour. C’est aussi elle qui introduit le fado dans les revues musicales, ce qui a permis à cette chanteuse de grand talent d’être une véritable star à son époque. Comme Lucília do Carmo, Fernanda Maria et Carlos Ramos, elle montera « O Solar da Hermínia », une « casa de fado ».

Lucília Do Carmo (1919-1998)

Elle n’était pas originaire de Lisbonne mais de Portalegre. Professionnelle dès l’âge de 17 ans, cette forte personnalité impose un style personnel tout d’énergie. En 1947, elle ouvre « A Adega da Lucília », casa de fado qui deviendra plus tard connu sous le nom de « Faia », et finalement enregistre peu. Son fils Carlos de Carmo est le fadiste qui connut le plus de succès dans les années 70 et 80.

Maria Teresa de Noronha (1918-1993)

Issue de la noblesse, elle fut une grande divulgatrice du fado. (elle était productrice d’une émission radiophonique bihebdomadaire). Elle ne s’adonnait qu’au « fado castiço » (authentique) et ne chantait pas de fado-cancão. Dans un style intimiste délicat, favorisé par les accompagnements de Raul Nery, elle s’attachait à la qualité poétique des paroles.

Amália Rodrigues (1920-1999)

Dans son livre Pensar Amália, Rui Vieira Nery, qui eut la chance de connaître la chanteuse dès sa plus tendre enfance, trace un portait tout de sensibilité qui nous la rend très attachante. Il confirme qu’elle ressentait un besoin désespéré d’être aimée et qu’elle avait un complexe d’autodidacte qui la poussait à se rapprocher de l’élite intellectuelle alors qu’elle avait une grande sensibilité artistique et un instinct naturel pour l’innovation. Dans son œuvre, il distingue la première époque d’or (1945-1959), avec les enregistrements pour Continental au Brésil et pour Ducretet – Thomson en France et il souligne la qualité du disque Ao vivo no Cafe Luso, paru seulement en 1995 mais qui nous la dévoile telle qu’elle était en public dans une grande « Casa de fado ». Nous renvoyons le lecteur à notre anthologie qui lui est dédiée chez Frémeaux. Il nous suffit de souligner que cette soprano agile, à la voix aigue et claire, possède un parfait contrôle de la respiration et que les suspensions inattendues et les ornementations nouvelles qu’elle introduisait ne pouvaient que fasciner son public. Elle a un temps accompagné l’évolution du fado puis, avec l’aide du franco-portugais Alain Oulman, et de quelques poètes, elle lui a donné une impulsion nouvelle.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

© 2013 Frémeaux & Associés

Bibliographie Selective

Ao Fado tudo se canta ? (Daniel Gouveia)

DG edições

Historia do Fado (Pinto de Carvalho Tinop)

Biblioteca de Etnografia e Antropologia

Publicações Dom Quixote

Para Uma Historia do Fado (Rui Vieira Nery)

Edição Público

Pensar Amalia (Rui Vieira Nery)

Tugaland

Amalia : Dos poetas populares aos poetas cultivados (Vasco Graça Moura)

Tugaland

Le Fado (Agnès Pellerin)

Chandeigne

Le Portugal (Pierre Léglise Costa)

Collection Idées Reçues

Le Cavalier Bleu Editions

Lisboa-Livro de bordo (José Cardoso Pires)

Publicações Dom Quixote

FADO (1949 - 1961)

Fado é destino marcado

Fado é perdão ou castigo

A propria vida é um fado

Que o coração traz consigo.

[Fado is destiny’s trace / Fado is pardon or punishment / Life itself is a fado / Carried within the heart.] Alcindo de Carvalho

Fado at the Teatro São Luiz

What fervour there was that night of May 25th 1963 at Lisbon’s Teatro São Luiz, and it was recreated by the record A Noite do Fado. It was the night Alfredo Marceneiro bade farewell to the stage – his first appearances had come in 1910, and he had turned professional in 1928 – and all the great voices were there as a tribute to fado’s legendary protector: Hermínia Silva, Lucília do Carmo, Fernanda Maria, Fernando Farinha and Maria Teresa de Noronha. The only voice missing was that of Amália Rodrigues, who was probably touring at the time. In the Fifties, for the first time in her life she had put words to music, Alfredo Marceneiro’s composition Fado Bailado. The result was the song Estranha forma de vida. Listening to that recording – legal reasons prevent its inclusion here – what does one feel? Immense regret at not being able to vibrate with the audience, to hear the particular texture of each voice – those modulations and embellishments which cause an artist to stand apart – and the close, magical presence of a legend, Alfredo Marceneiro. Even if one doesn’t understand Portuguese, one can sense that this was a voice carrying the deep song and nobility of the whole community living in Lisbon’s popular quarters. In 1963, there remained another eleven years of a fascistic dictatorship for them to endure, and fado, despite the Estado Novo’s moral reservations, remained “popular” in both senses: fado spoke to the people, and it was fashionable enough for record-companies to invest in it. In some way, the Fifties and Sixties marked the zenith of fado: it was recorded well, and press and radio paid sufficient attention to it that it no longer appeared as merely the music of Lisbon, but spread wider as the expression of the Portuguese soul.

The history of fado

Fado – the word has the Latin origin fatum, fate or destiny – emerged slowly after maturing for almost a century and a half; it was specific to the urban life of Lisbon before gaining an identity as the national music of Portugal. Its rise was inextricably linked to the cultural, political, social and economic life of the country – Portugal went from monarchy to civil republic and, between 1928 and 1974, to the dictatorship of the Estado Novo – and one of the markers of the country’s sound-identity, whether inside Portugal or abroad, is the particular, plaintive sound of the “Portuguese guitar” – 12 metal strings played over 17 frets and covering three and one half octaves –, an instrument evolved from the lute and the so-called English guitar of the 18th century. To understand how its values moved – like a pendulum – over the next decades, between the ideals of the Proletarian Left and Conservatism, between the struggle for a better destiny and submission to fatalism, it may be useful to sketch out various great historical eras, but not return to old quarrels over the sources and influences which permitted the genre to bloom – Moorish or Brazilian influences, those of other great capitals such as London, Vienna, Paris – because, when all is said, such debates should be treated with caution. So, as a synthesis, it can be said that fado is an authentic music-genre more than a hundred years old, and it was born in Lisbon, a seaport open to a mixture of cultures coming from overseas, but also a capital where people from poor, rural areas of Portugal converged: remember that the father of Severa, the first recognized fadista, originally came from Santarem, that Amália Rodrigues always acknowledged the influence of the lullabies sung to her by her mother born in the Beira Baixa region on the Spanish border, or that Alfredo Marceneiro’s father came from Cadaval.

In the course of the second half of the 19th century, Brazilian genres which were popular at the time, like the lundum (an Afro-Brazilian dance) and the modinha (a romantic song), gave way to a more Lusitanian genre – it wasn’t for dancing – in which song was mixed with music; it quickly left its original milieu of cheap restaurants and brothels to spread through popular districts where aristocratic Bohemians went slumming. As in Brazil, and the world of the sambistas, singers were soon given names based on either their profession or some particular characteristic: there was Chico Torneiro (a plumber), Antonio da Praça (meaning “from the square”), the self-explanatory Epifanio Mulato, or else Jorge Sapateiro (a shoemaker)… The most famous of them today remains Alfredo Marceneiro, who was a cabinetmaker by trade. There were associations whose work aimed to increase literacy, and during the days of the Republic, fado took on social and anticlerical colours before the moralizing conservatism of Salazar’s Estado Novo sought to extinguish their ardour. And then, little by little, the identity of the fadista changed: the singer wasn’t exactly paid to sing, but invited to appear in salons where the singer was rewarded with valuable gifts. It was the first step towards a fully professional status which became the rule in the Thirties under the impetus of musicals and 78rpm records, even though it was also imposed by the dictatorship following the promulgation of a labour-law directive. Those Thirties were also marked by the appearance of a new kind of establishment known as the casa de fado [or “house of fado”], whose clientele was less popular and more select. But they were fans all the same, and tales were told of intellectuals who would spend an entire night going from one casa to another. Those were the days of such major artists as the singers Ercília Costa, Berta Cardoso and Maria Alice, or the guitarist & composer Armandinho. Of course, with professionalism, some of the salt of poetic and musical improvisation was lost: the environment was more ritualistic, although pure fados – castiços – were perpetuated. In the grip of the censor, the texts written for fadistas congealed around themes filled with pathos, far from the sensibilities of former years, whilst performers tended to confine themselves to the three-minute limits imposed by 78rpm recordings... And yet there remained an extraordinary artistic vitality which favoured emulation and creativity: artists would be judged by audiences according to their ability to give inflamed, personalized versions of songs; artists freely added musical flourishes around a sustained note, for example; there was an osmosis between strings and voice; improvisation on the guitarra at key moments... The artists who appear in this anthology are those who enjoyed the most renown in those Forties and Fifties. Carlos Ramos and Alfredo Marceneiro here substantiate the fact, in the same mould, and with identical purpose, two imperative aesthetics opposed each other, and it is extremely difficult to prefer one over the other. Each time fado evolved there were people to say that it lost some of its purity, but that did little to change that “ideological pendulum”-movement which lasted right up until the end of the Seventies: it swayed between ‘Proletarian Left’ – which detested fado’s fatalism and its acceptance of social and political conditions – and ‘Conservative Right’, which reproached fado for its immorality, its lack of social respectability, and its growing distance from the rural themes of singing-groups in the provinces.

Some aesthetic rules

All good fado singers must meet certain criteria in order to be recognized by their peers and by connoisseurs. Some are obvious, whilst others are more specific to the Lisbon fado-genre based on popular songs from the streets. As with jazz-singers, the performer must have a true voice and a sense of phrasing – it almost goes without saying – and, above all, know how to “assert character”. The Portuguese word is estilar, and maybe a better definition would be to say “capable of varying the melody line between verses with the introduction of improvised embellishments”. This is the notion of a performer’s powers of expression and his capacity for ornamentation and word-association (the Portuguese formula is dividir): it is imperative that the fadista’s breathing and accents comply with fado’s specific codes in order to highlight the lyrics, since fado, according to one definition, is above all a dance between words. Didn’t Alfredo Marceneiro himself say, “It’s not the voice which counts the most in fado; above all, you have to know how to say the words and separate the verses, drawing attention to their intent.” Contrary to flamenco, however, fado song is austere; its expressivity is contained, and the pose and gestures almost totally motionless. Alfredo Marceneiro is said to be the first to have sung while standing with his hand in his pocket, and Amalia Rodrigues the one to have first stood in front of the musicians. On the stage, fado imposes the entendimento, which provides the supporting harmony and rhythm. The instrumental prelude, sometimes rather long in public performances, is where the strings set the general tempo taken by the voice of the fadista in beginning to juggle with the bars of a song. Another code: the last reprise of the chorus or the last refrain is always announced by a voice in a drawl, with the finale ending on a crescendo fortified by strong chords from the guitars, one accentuated by the singer’s hands so as to fix the melodramatic emphasis. Even if any listener, often unwittingly, focuses on the musical nature of the voice, it is recommended that this musicality should be apprehended within the often-hallucinatory dynamics provided by the strings (the “Conjunto de guitarras” with two guitarras, a viola and a viola baixo, by Raul Nery, was a model of the genre).

As popular music, fado evolved from its simplest expression to its most complex. The fados castiços, the oldest forms – and the purest, according to traditionalists – are the fado corrido in D, the fado menor in E and the fado mouraria in G. These fados tell a story with a beginning, middle and end spread over an indefinite number of quadras, or verses. The differences between fado corrido and fado mouraria lie in the introductions which are specific to each, and in the differing accentuation which impacts the way in which the singer “spins” his tale. In the evolution of the genre, the next fados had two keys – with four chords, different fingering on the strings, alternation between the major key and its minor relation, a more elaborate melody giving more room for variations –, and then, with musicals, came the fado-canção: said to have more subtlety in melody and harmony, this form, as in a classic song, was divided into verse and chorus, but it effaced all improvisation, contrary to “authentic” fado (the castiço).

Coimbra Fado

As early as the 17th century, the University of Coimbra was renowned throughout Europe – a visit to its fabulous library still imposes silent serenity – and Coimbra, albeit somnolent in the summer sun, remains a magical city where days pass peacefully by along the banks of the Rio Mondego. Whenever the subject of fado is raised, Lisbon Fado – said to be more Bohemian, or vadio in Portuguese – is usually contrasted with Coimbra Fado, which is more erudite and romantic; some even go so far as to say that it is more correct to refer to Coimbra “Song” rather than “Fado”. And, in fact, one only has to put on a record by José Afonso or Luis Góes to be convinced that a whole world separates the genre born in Lisbon’s seven hills from the fado which originated along the Rio Mondego.

To my mind, in his book Ao Fado tudo se canta Daniel Gouvea draws an excellent synthesis of the genres’ aesthetic differences; he points out the essentials, covering instrument-making and dress as much as lyrics, compositions or the way the voice is carried. In substance, he writes, “Lisbon fado has popular roots (fadistas, until the Fifties, were often semi-literate, as testified by certain manuscript-reproductions on one of the walls in the Museu do Fado), whereas Coimbra fado came from the intellectual, university elite of Portugal and its former colonies. The Lisbon fado is above all a song of intimacy and contemplation, while the Coimbra fado is more extroverted, like the serenata, the serenade sung beneath a young girl’s balcony. The Lisbon fado was created above all by people of Lisbon who could of course have rural family roots, but they identified themselves deeply with their city, whereas Coimbra fado was created by students who were not born along the Mondego, but came from horizons as diverse as the Azores, Madeira, Brazil or any other region of Portugal.”

It’s true that the members of the Paredes family – Gonçalo, the father, Artur, the son, and Carlos, the grandson, all prodigious soloists playing the guitarra portuguesa – were originally from Coimbra, but they never attended its University due to their modest origins. The song in Lisbon fado embraces everyday language, and its melodies fold themselves naturally into the texts, whereas, as with all learned music, the lyrics of Coimbra’s songs follow the melody line. In Lisbon, as with all popular genres, no matter if the voice is male or female, hoarse or veiled, or has a timbre that is barely orthodox; but Coimbra’s fado borrows from operatic song, and prefers masculine voices, often tenors. The fadista’s appearance, too, is different. In Coimbra, they wear the black uniforms of students, while in Lisbon they dress as they like, often with a “dandy” touch like Alfredo Marceneiro had (cap, silk scarf, cigarette, a hand in a pocket); female singers wear a shawl, but its colour is different and it can be worn over any kind of dress. There are also differences in the way women are considered: in Lisbon fado, women are treated as equals, whereas in Coimbra, as with troubadours and Romantics, women are placed on a pedestal and almost out of reach. Even the instruments are different: tunings, timbres, techniques, even body-dimensions (the Coimbra guitar is more slender, whilst the width of the Lisbon instrument is greater than its length). The Coimbra guitar is intended to accompany male voices, and so has a deeper, harsher sound, with a longer arm.

The great names of Coimbra

One understands from the above that the historical sources of Coimbra fado lie elsewhere; but the genre nonetheless remains a natural child of the Lisbon genre. The man recognized as the founder of the Coimbra serenata was Augusto Hilário, a very Bohemian student born in 1864 – he died young at the age of 32 – and people refer to his style as fado Hilário. The generation of the Menano brothers (Francisco, Alberto, Horacio and Antonio) and their friends Almeida d’Eça and Paulo de Sá, saw the emancipation, definition and final consolidation of the genre in the Thirties. The record-company EMI-Valentim de Carvalho has magnificent releases of 78rpm discs made by Doutor Menano, and other names are Antonio Portugal and Manuel Morra (guitarists), Manuel da Costa Braz and Antonio Serrão (viola players), and singers Luis Góes and José Afonso. Artur Paredes, a bank employee who went to live in Lisbon at the end of the Thirties, left some monumental local music, and it’s imperative to listen to his 1961 recordings made with his son Carlos, with Arménio Silva on viola, which have been reissued on CD by Alvorada. It seems that Edmundo Bittencourt was also a very good singer with a crystal-clear voice. In 1955, Fernando Machado Soares, assisted by Antonio Portugal, formed a group with Jorge Caldeira (second guitarra), and viola players Manuel Pepe and Levy Baptista. In 1957 they would record in Madrid for Philips, and those titles can be found here, although Machado Soares had fallen ill and was replaced at the last-minute by Luis Góes. The LP which they recorded – it went down in history under the title “Coimbra Quintet” – became a best-seller, the record of the music of Coimbra which has sold the most. The Sixties – without any abrupt break in ties with past culture – would stand out due to a more pronounced fight against the dictatorship. When it appeared in 1969, the record “Flores para Coimbra” was sung by Antonio Bernardino, with compositions by Antonio Portugal, Francisco Martins and Luis Filipe. After the Carnation Revolution of 1974, black capes and cassocks – seen as marking the identity of reactionary forces – were banned. It is also worth noting that Antonio Menano (b.1895 d.1969) was a doctor of medicine; Antonio Brojo (b.1927) was a pharmacy professor; Luis Góes (b.1933) was a dentist,

like the Coimbra writer Miguel Torga; Antonio Portugal (b.1931) was a lawyer and jurist; and Machado Soares, born in 1930 in the Azores, was a magistrate and close friend of José Afonso, whose “Grândola Vila Morena” was chosen by the military to signal the beginning of operations during the Carnation Revolution... It gives one a clear idea of the social differences between Coimbra artists and their Lisbon counterparts.

Authors, Composers and Instrumentalists

Before we come to the portraits of the singers heard in this anthology, some valued instrumentalists must be mentioned: without them, the savour of fado would not be the same. The guitarrista Armandinho (Armando Augusto Freire, b.1891 d.1946) was taught by Petrolino, himself a pupil of João-Maria dos Anjos – in the evolution of fado, this alone shows the value of transmitting skills from one master to another – and Armandinho left us superb compositions with rhapsodic accents, not to mention solo recordings where we can imagine his talent for improvisation in front of an audience… Raul Néry (b.1921) was only eighteen when he played the second guitarra alongside Armandinho, and later he accompanied Amália Rodrigues for some twenty years... In 1959, Néry formed his famous “Conjunto de Guitarras” group, with José Fontes Rocha (guitarra), Julio Gomes (viola) and Joel Pina (viola baixo). His son Rui Vieira Néry is a musicologist who has written two books on the subject of fado, both of them essential works. Jaime Santos (b.1909 d.1982) was for a long time the accompanist of Martinho d’Assunção, who played the viola and whose father was a socialist militant; Santos was a renowned composer and virtuoso who left many recordings. One can also mention Francisco Carvalinho, Casimiro Rocha and Domingos Camarinha (b.1915 d.1993) who accompanied Amália Rodrigues between 1954 and 1966.

With fado being defined by some as a “dance between words”, we must not forget to mention “popular” lyricists such as Artur Soares Pereira – he was responsible for the stocks at São José Hospital and refused to be called a poet –, Frederico de Brito (a taxi driver) and Linhares Barbosa (a metal-worker who operated a milling-machine). The talents of the latter two were such that they were constantly solicited. But fado also called on lyricists who were intellectuals, like David Mourrão Ferreira, who was the brother-in-law of Valentim de Carvalho, a university-professor and a recognized essayist and poet who was State Secretary for Culture in the first government of Mario Soares; others were João Silva Tavares, Alexandre O’Neill, Luis de Macedo and Manuel Alegre. Nor should we forget the composers: Frederico de Freitas, who attended the conservatório, left numerous ballet scores; Frederico Valerio (b.1913 d.1982) wrote music for Amália Rodrigues until the end of the Fifties (Confesso, Fado do Ciume, Sabe-se lá); his successor was Franco-Portuguese composer Alain Oulman (b.1928 d.1990), who was related to the family of the French publisher Calmann-Levy, and Oulman contributed 22 pieces to eight albums by Amália Rodrigues.

Portraits of the artists

Carlos Ramos

This distinguished artist, a sober and discreet musician both on a stage and on record, deserved to be better-known for his work: it was filled with the sensibilities of the true fadista. He was born on October 10th 1907 and died of thrombosis on November 9th 1969. He came from a modest family living in Alcantara and had to abandon his studies in medicine after the death of his father. As a guitarist he was good enough to play at the Retira de Severa, the Café Luso and the Café Mondego, and he accompanied Ercília Costa – one of fado’s most important voices – before deciding, at the age of forty, to become a singer himself. His favourite genre was fado-canção, which was better-suited to his artistic temperament and his skills as a storyteller. He appeared in a few films and television programmes, made almost twenty records (78rpm, EP and LP) and opened his own casa de fado named “A Toca” in 1959 before a heart ailment caused him to abandon music. Thanks to his velvet voice – not too plaintive – and his perfect phrasing and respiration, he became one of the greatest singers in the history of fado.

Alfredo Marceneiro

Alfredo Rodrigo Duarte was born in February 1891 in the Lisbon parish of Santa Isabel, where he lived all his life; he died there in June 1982 leaving five children. He was something of a dandy in his dress, which earned him the nickname Alfredo Lulu, but the history books use the name Marceneiro. A picture of him in a cap with a cigarette dangling from his lips, wearing a silk scarf to protect his throat, and one hand in his pocket, became a caricature for the 20th century fadista. He came from a humble family and left school at thirteen, obliged to cater to the needs of his family after the death of his father. He quickly showed he was an extremely gifted improviser of verse – he was said to have introduced alexandrines into fado at a time when decasyllabic verse was the rule – and by the end of the 20’s the fado milieu had adopted him. He appeared alongside Armandinho, Filipe Pinto and Julio Proença, all of them leading figures of the day. He was a cabinet-maker by trade, making furniture for ships, and was sent to prison in 1943 after going on strike (manual workers were clamouring for an eight-hour day); on his release he decided to turn professional and never work for an employer again. He preferred public performances to recording (he regularly appeared in the casas de fado), which explains his relatively short discography – he even once confessed that making records seemed to him to be like talking to a machine –, and he recorded only 4 LPs and 3 EPs from 1961 to 1963. He was self-taught and composed by ear: his guitarists annotated his improvisations so that he could register the scores at the writers’ society. He was very direct, and his sudden changes of mood sealed his reputation: once, after a guitarist muffed his entrance following the introduction, he shouted at him saying, “I was a singer before you stopped wetting yourself”… Stylistically, he began with traditional fado songs whose structure was simple and repetitive, but he converted these using compositional methods which became his signature. He owed his great reputation more to his feeling for energy and scansion than the purity of his singing, and his impact on listeners was as strong and spellbinding as that of the sambista Nelson Cavaquinho. Fernanda Maria was the only singer who would have the right to measure up to him in the improvisation-duel called a descarraga.

Fernando Farinha (1928-1988)

He was known as “O Miúdo da Bica” after he sang in a competition organized in Lisbon’s bairro at the age of nine, and he was given special permission to turn professional when he was eleven due to the death of his father. He was a prolific singer and rather full of himself (often the case with singers who are tenors), and he made his first record in 1940. He also composed for others, notably writing Isto é Fado for Fernanda Maria, O Teu olhar for Carlos Ramos, or Lugar Vazio for Hermínia Silva, before his career went into decline in the Sixties.

Hermínia Silva (1913-1993)

She was born only five years after Ercília Costa, and brought a less tragic dimension to fado, with songs which were humorous critiques of society. She was also the woman who introduced fado into musical revues, where her talents made her a genuine star of her day. Like Lucília do Carmo, Fernanda Maria and Carlos Ramos, she too would open her own casa de fado named “O Solar da Hermínia”.

Lucília Do Carmo (1919-1998)

Lucília came from Portalegre, not Lisbon, and became a professional at the age of seventeen. Her strong personality helped her to establish an individual style which was filled with energy. In 1947 she opened “A Adega da Lucília”, a casa de fado later known as “Faia”, but she made few recordings. Her son Carlos de Carmo was the most successful fadista of the Seventies and Eighties.

Maria Teresa de Noronha (1918-1993)

Her family were aristocrats and the radio programme which she produced every fortnight turned her into fado’s greatest promoter. She sang only fado castiço, the “real” genre which she preferred to fado-cancão, and her intimate, delicate style, which was ideally complemented by Raul Néry’s accompaniment, showed her attachment to the poetic qualities of fado lyrics.

Amália Rodrigues (1920-1999)

Rui Vieira Nery was fortunate enough to know Amália Rodrigues from her infancy, and his book Pensar Amália draws a very attractive, sensitive portrait of her. He confirms that she felt a desperate need to be loved; as a self-taught singer she had a complex which moved her to frequent the intellectual elite despite her great artistic sensibilities and natural instinct for innovation. Nery’s biography draws particular attention to her first Golden Age (1945-1959), when Amália was recording for Continental in Brazil and Ducretet-Thomson in France; he emphasizes the quality of her record Ao vivo no Cafe Luso, which didn’t appear until 1995 but reveals her as audiences saw her when she was appearing at a great casa de fado. An anthology devoted to her work has been released on the Frémeaux label. She possessed an agile, high-pitched soprano voice of great clarity, and she had perfect control over her breathing; the unexpected suspensions and new ornamentations she introduced could only fascinate her audiences. For a time she accompanied the evolution of fado before giving the genre a new impulse with the help of Franco-Portuguese composer/producer Alain Oulman and several poets.

Adapted from the french test of

Teca Calazans and Philippe Lesage

by Martin Davis

© 2013 Frémeaux & Associés

DISCOGRAPHIE - CD 1

1 - ADEUS MOURARIA

(Artur Ribeiro)

Carlos Ramos, guitarra : Raul Nery, viola : Santos Moreira

Columbia ML 191 1958

2 - SENHORA DO MONTE

(Gabriel de Oliveira /Alfredo Duarte)

Alfredo Marceneiro, guitarra : Carvalhinho, viola Martinho d’Assunção

LP Columbia CSX 21 - 1961

3 - VIELAS DA ALFAMA

(Artur Ribeiro / Max)

Carlos Ramos, guitarra : Francisco Carvalhinho, viola : Martinho d’Assunção

EP Columbia n° SEGC 15 - 1958

4 - BAIRROS DE LISBOA

(Carlos Conde / Alfredo Duarte)

Alfredo Marceneiro, Desgarada com Fernanda Maria, guitarra : Francisco Carvalinho, viola :Pais da Silva – EP A Voz do Dono, 7 LEM 3019, 1960

5 - FOI A TRAVESSA DA PALHA

(Gabriel de Oliveira / Frederico de Brito)

« Fado Britinho » Lucília do Carmo, guitarra : Francisco Carvalhinho, viola : Martinho d’Assunção

EP Decca P-DFE 6497, 1958

6 - A NOVA TENDINHA

(Carlos Lopes / Anibal Nazaré / Carlos Dias)

Hermínia Silva, guitarra : Raul Nery, viola : José Mendes, viola baixo : Alfredo Mendes

EP Decca n° P-DEF 6523, 1958

7 - BALADA DE COIMBRA

(J. Elyseu)

Coimbra Quintet

Philips P 10141 R - 1957

8 - EU JÁ NÃO SEI

(Domingos Gonçalves da Costa / Carlos Rocha)

Carlos Ramos, guitarra : Jaime Santos, viola : Martinho d’Assunção

EP Columbia n° SLEM 2.095 – 1961

9 - FADO RIBATEJANO ( D. R.)

Hermínia Silva, guitarra : Raul Nery, viola : José Mendes, viola baixo : Alfredo Mendes)

EP Decca n° P-DEF 6523 – 1958

10 - FADO HILÁRIO

(Augusto Hilário)

Amalia Rodrigues c/ acompanhamento

Columbia CQ 3271 - 1956

11 - CANÇÃO DE LISBOA

(Fernando Farinha / Jaime Mendes)

Fernando Farinha com Conjunto de Guitarras de Raul Nery

EP Parlophone n°LMEP 1071 – 1960

12 - FADO TRISTE

(Dr. F. Menano)

Coimbra Quintet

Philips P 10141 R - 1957

13 - MOURARIA

(Maria Helena B. Guerreiro/ Jaime Santos)

Maria Teresa de Noronha , guitarra : Raul Nery, viola : Joaquim do Vale, viola baixo : Joel Pina – LP Decca SLPDX 501 – 1961

14 - VARIAÇÕES EM RÉ MENOR

(Dr. A. Santos)

Coimbra Quintet

Philips P 10141 R - 1957

15 - OLHOS GAROTOS

(Linhares Barbosa / Jaime Santos)

Lucília do Carmo, guitarra : Francisco Carvalhinho, viola : Martinho d’Assunção

EP Decca P-DFE 6496 – 1958

16 - A MINHA FREGUESIA

(Armando Neves / Alfredo Duarte)

Alfredo Marceneiro e Conjunto de Guitarras de Raul Nery, guitarra :Raul Nery e Fontes Rocha, viola : Júlio Gomes, viola Baixo : Joel Pina

EP Columbia SLEM 2108, 1962

17 - BELOS TEMPOS

(Fernando Farinha / Júlio de Souza) « Fado Loucura »

Fernando Farinha, Conjunto de Guitarras de Raul Nery

EP Parlophone n°LMEP 1071 – 1960

18 - COIMBRA

(José Galhardo / Raul Ferrão)

Amália Rodrigues, guitarra : Domingos Camarinha, viola: Santos Moreira,

LP Columbia FSX 123 – 1957

DISCOGRAPHIE - CD 2

1 - MI DESEO

(Meu Desejo) (Luis Góes)

Coimbra Quintet

Philips P 10141 R - 1957

2 - VEIO A SAUDADE

(Anibal Nazaré / Miguel Ramos)

Carlos Ramos, guitarra : Raul Nery, viola : Santos Moreira

EP Columbia n° SEGC 15 - 1958

3 - A CASA DA MARIQUINHAS

(Silva Tavares / Popular / Alfredo Duarte)

Alfredo Marceneiro, guitara : Francisco Carvalhinho, viola Martinho d’Assunção

LP Columbia CSX 21 – 1961

4 - LISBOA ANTIGA

(Amadeu do Vale / José Galhardo / Raul Portela)

Hermínia Silva, guitarra : Raul Nery, viola : José Mendes, viola baixo : Alfredo Mendes)

EP Decca n° P-DEF 6523 – 1958

5 - SEMPRE QUE LISBOA CANTA

(Carlos Rocha / Anibal Nazaré)

Carlos Ramos, probablement : guitarra Raul Nery, viola : Santos Moreira

Columbia, 1957

6 - RAPSODIA DE FADOS

(Linhares Barbosa / Popular )

« Fado Menor », « Fado Corrido », « Fado dois Tons », « Fado sem Pernas » « Fado Mouraria » Lucília do Carmo, guitarra : Francisco Carvalhinho, viola :

Martinho d’Assunção

EP Decca P-DFE 6496 – 1958

7 - BEIJO EMPRESTADO

(Fernando Farinha / Alberto Correia)

Fernando Farinha com Conjunto de Guitarras de Raul Nery

EP Parlophone n°LMEP 1072 – 1960

8 - MOCITA DOS CARACÓIS

(Linhares Barbosa / Alfredo Duarte)

Alfredo Marceneiro, guitara : Francisco Carvalinho, viola Martinho d’Assunção

LP Columbia 33 CSX 21 – 1961

9 - TOADA BEIRA

(Arr. Luis Góes)

Coimbra Quintet

Philips P 10141 R - 1957

10 - ALEXANDRINO

(Carlos Freire / Alfredo Duarte)

Maria Teresa de Noronha , guitarra : Raul Nery, viola : Joaquim do Vale, viola baixo : Joel Pina – LP Decca SLPDX 501 – 1961

11 - FADO PRIM PRIM

(F. Valerio / A. Nazaré)

Hermínia Silva

Alvorada MLD 8007

12 - SERRA D’ARGA

(Arr. M. Soares)

Coimbra Quintet

Philips P 10141 R - 1957

13 - MARIA DA GRAÇA

(Artur Ribeiro)

Carlos Ramos, guitarra : Raul Nery, viola : Santos Moreira

Columbia ML 191 - 1958

14 - FADO DA SAUDADE

(F. de Freitas / S. Tavares)

Amália Rodrigues, guitarra : Jaime Santos, viola : Santos Moreira

Continental 20.135 –A, 1952

15 - MATARAM A MOURARIA

(José Mariano / Manuel Maria Rodrigues)

Maria Teresa de Noronha, guitarra : Raul Nery, viola : Joaquim do Vale, viola baixo : Joel Pina

LP Decca SLPDX 501 – 1961

16 - PODEMOS SER AMIGOS

Lucília do Carmo, guitarra : Jaime Santos, viola : Martinho d’Assunção

EP Decca P-DFE 6496 – 1958

17 - AQUARELA PORTUGUESA

(A. Portugal)

Coimbra Quintet

Philips P 10141 R - 1957

18 - O CHICO DO CACHENÉ

(Linhares Barbosa / Casimiro Ramos) « Fado Helena »

Fernando Farinha com Conjunto de Guitarras de Raul Nery

EP Parlophone n°LMEP 1072 – 1960

19 - FADO DO ESTUDANTE

(M. Soares)

Coimbra Quintet

Philips P 10141 R - 1957

Né à Lisbonne, capitale portuaire qui fut le point d’ancrage et de métissage de cultures venues de l’au-delà des océans (Brésil, Açores, Afrique...) et des provinces rurales du Portugal, le fado est un genre musical populaire authentique plus que centenaire. Il est porté, dans notre anthologie qui couvre les belles années cinquante, par Amália Rodrigues, son héroïne principale, par la figure mythique d’Alfredo Marceneiro, par la voix splendide de Carlos Ramos ainsi que par les artistes de l’autre branche du Fado, celui de Coimbra.

Philippe Lesage & Teca Calazans

Fado is an authentic music-genre more than a hundred years old, and it was born in Lisbon, the capital famous as the seaport where a mixture of cultures came to anchor after crossing the oceans separating the Azores from Brazil and Africa. In this anthology, which spans the Fifties, the beautiful sounds of Fado are carried by the voices of the genre’s principal heroine, Amália Rodrigues, the legendary Alfredo Marceneiro and the splendid singer Carlos Ramos, together with artists representing the other face of Fado, the Coimbra style.

CD Fado Amália Rodrigues, Lucília do Carmo, Hermínia Silva, Fernando Farinha, Carlos Ramos, Maria Teresa de Noronha, Alfredo Marceneiro Coimbra - Lisbonne 1949 - 1961 © Frémeaux & Associés 2013