- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

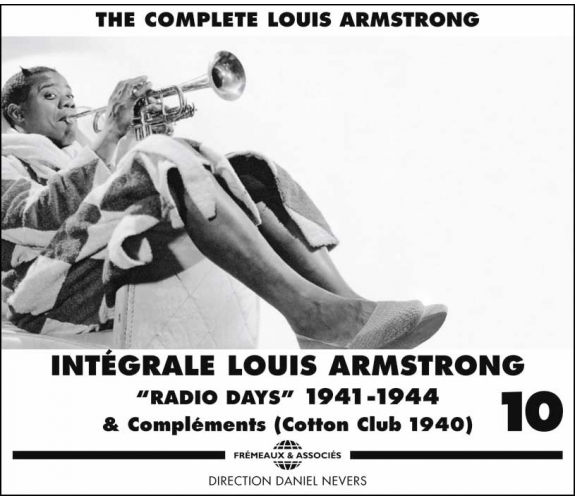

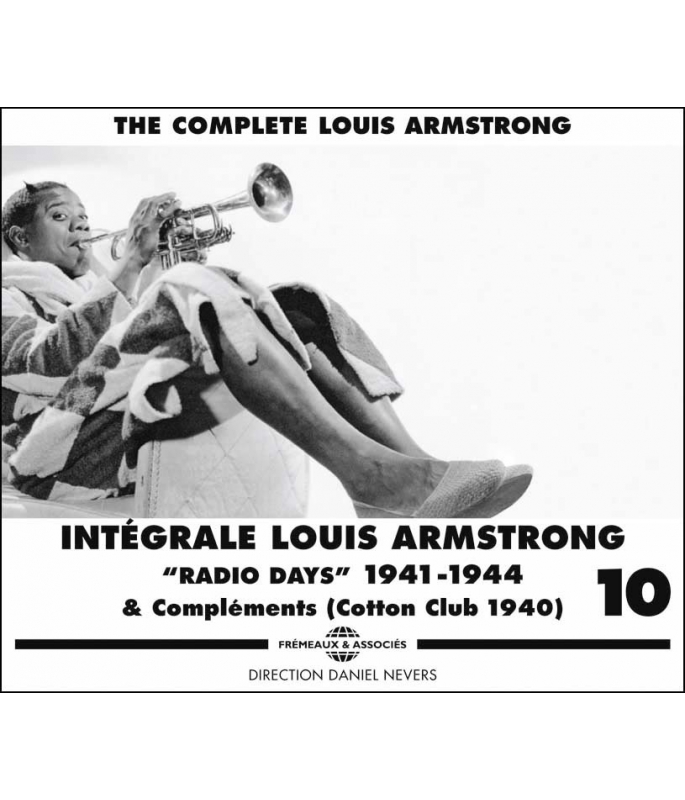

RADIO DAYS 1941-1944

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

Ref.: FA1360

EAN : 3561302136028

Direction Artistique : DANIEL NEVERS

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 3 heures 44 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

RADIO DAYS 1941-1944

La radio ? Sûr qu’il connaissait, Louis Armstrong. Dès 24-25, quand il jouait chez Fletcher Henderson.

Même que c’est comme cela que le jeune Cootie Williams l’a découvert : le soir sur les ondes courtes, en douce… En 1926, à Chicago, le Hot Five, qui n’existait pourtant que pour le disque, a fait des émissions. Puis il y en a eu en Europe. En 37, Louis est même devenu une authentique vedette des ondes sur un grand réseau.

Mais là, pendant la guerre, c’est le patriotisme qui mène la danse, grâce à l’AFN (American Forces Network) et aux transcriptions de l’AFRS (Armed Forces Radio Service). Ce volume 10 de l'Intégrale Louis Armstrong, presque uniquement constitué de diffusion radiophoniques enregistrées donne l'occasion d'entendre Armstrong en-dehors du format disque, dans toute la liberté permise par les ondes…

Daniel Nevers

Les intégrales Frémeaux & Associés réunissent généralement la totalité des enregistrements phonographiques originaux disponibles ainsi que la majorité des

documents radiophoniques existants afin de présenter la production d'un artiste

de façon exhaustive.

L'intégrale Louis Armstrong déroge à cette règle en proposant la sélection la plus complète jamais éditée de l'oeuvre du géant de la musique américaine du XXè siècle, mais en ne prétendant pas réunir l'intégralité des oeuvres enregistrées.

Patrick Frémeaux

Radio? Of course he’d heard of it; Armstrong had been playing with Fletcher Henderson in 1924-1925, hadn't he? It was even how the young Cootie Williams discovered him, sneaking a listen to him on short-wave radio in the evenings... In 1926, in Chicago, the Hot Five had done broadcasts even though the group only existed on records. And then there were programmes in Europe. In 1937 Louis even became a genuine radio-star on a national network. But when the war came, patriotism was the word, thanks to the AFN and the AFRS transcriptions...

Daniel Nevers

The Frémeaux & Associés Complete Series usually feature all the original and available phonographic recordings and the majority of existing radio documents for a comprehensive portrayal of the artist. The Louis Armstrong series is an exception to the rule in that the selection of titles by this American wizard is certainly the most complete as published to this day but does not comprise all his recorded works.

Patrick Frémeaux

CD 1 :

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (DECCA SESSION, 16/11/1941) : WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH • LEAP FROG • I USED TO LOVE YOU (TK.A) • I USED TO LOVE YOU (TK.B) • YOU RASCAL, YOU. LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (RADIO – 17 & 27/11/1941) : BASIN STREET BLUES • EXACTLY LIKE YOU • PANAMA & THEME (SLEEPY TIME…). LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (RADIO – 04/1942) : THEME & SHINE • SHOE SHINE BOY • A ZOOT SUIT • BASIN STREET BLUES • YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT LOVE IS • BLUES IN THE NIGHT • (GET SOME) CASH FOR YOUR TRASH. LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (DECCA SESSION, 17/04/1942) : (GET SOME) CASH FOR YOUR TRASH • AMONG MY SOUVENIRS (TK.A) • AMONG MY SOUVENIRS (TK.B) • COQUETTE • I NEVER KNEW • LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (FILM SOUNDTRACKS, 20/04/1942) : SWINGIN’ ON NOTHING • YOU RASCAL, YOU • SHINE.

CD 2 :

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (FILM SOUNDTRACK, 20/04/1942) : WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH. LOUIS ARMSTRONG & STUDIO ORCHESTRA (FILM “CABIN IN THE SKY” SOUNDTRACK, 28/08/1942) : TRUMPET BREAK & AIN’T IT THE TRUTH. LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (RADIO - AFRS SERIES, 1942-43) : THEME, PRESENTATION & COQUETTE • L. ARMSTRONG INTERVIEW PAR/BY DICK JOY • I GOT A GAL IN KALAMAZOO • SLENDER, TENDER AND TALL • DEAR OLD SOUTHLAND • LAZY RIVER • YOU CAN’T GET STUFF IN YOUR STUFF • ME AND BROTHER BILL • ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET • THEME, PRESENTATION & COQUETTE • TEXTE & SHINE • LAZY RIVER • TEXTE & ONE O’ CLOCK JUMP • PRESENTATION & IF I COULD BE WITH YOU… • TEXTE & CONFESSIN’ • IN THE MOOD • I CAN’T GIVE YOU ANYTHING BUT LOVE & THEME.

CD 3 :

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (RADIO – 1943) : ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET • BACK O’ TOWN BLUES • AS TIME GOES BY. LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (RADIO – AFRS SERIES, 1943) : THEME, PRESENTATION & LEAP FROG • OLD MAN MOSE • AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ • BARRELHOUSE BESSIE FROM BASIN STREET • THE PEANUT VENDOR • SLENDER, TENDER AND TALL. LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (FILM “JAM SESSION” SOUNDTRACK, 23/04/1943) : I CAN’T GIVE YOU ANYTHING BUT LOVE. LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (RADIO – AFRS SERIES, ? 08/ 1943) : PRESENTATION & I NEVER KNEW • WHAT A GOOD WORD, MR. BLUEBIRD ? • I LOST MY SUGAR IN SALT LAKE CITY • LAZY RIVER. “CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY OF LOWER BASIN STREET” (RADIO - 16/01/1944) : ESQUIRE BOUNCE • BASIN STREET BLUES • HONEYSUCKLE ROSE. 1940 COMPLEMENTS : “COTTON CLUB” DATES… LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (RADIO – 03 & 04/1940) : THEME & KEEP THE RHYTHM GOING • CONFESSIN’ • STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE • DARLING NELLY GRAY • SONG OF THE ISLANDS.

Droits : DP/ Frémeaux & Associés.

JEEPERS CREEPERS - 1938-1941

CONSTELLATION 48

CHIMES BLUES 1923-1924

1923 - 1948 - L'intégrale en 45 CD

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1When It's Sleepy Time Down SouthLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLeon René & Otis René00:03:141941

-

2Leap FrogLouis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:03:011941

-

3I Used To Love You (tk.A)Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:02:531941

-

4I Used To Love You (tk.B)Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:03:011941

-

5You Rascal YouLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraSam Theard00:03:011941

-

6Basin Street BluesLouis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:03:071941

-

7Exalctly Like YouLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraDorothy Fields00:03:551941

-

8Panama And ThemeLouis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:03:191941

-

9Theme And ShineLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraCecil Mack00:03:581942

-

10Shoe Shine BoyLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraSammy Cahn00:03:071942

-

11A Zoot SuiteLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraRay Gilbert00:02:521942

-

12Basin' Street BluesLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraSpencer Williams00:03:131942

-

13You Don't Know What Love IsLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraDon Raye00:04:471942

-

14Blues In The NightLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJohnny Mercer00:03:271942

-

15Cash For Your TrashLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraFats Waller00:03:061942

-

16Get Some Cash For Your TrashLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraFats Waller00:03:051942

-

17Among My Souvenirs (tk.A)Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraHoratio Nichols00:02:491942

-

18Among My Souvenirs (Tk.B)Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraHoratio Nichols00:02:331942

-

19CoquetteLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraGus Kahn00:02:381942

-

20I Never KnewLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraGus Kahn00:02:481942

-

21Swingin' On NothingLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraSy Oliver00:03:061942

-

22You Rascal YouLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraSam Theard00:02:581942

-

23ShineLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraCecil Mack00:02:351942

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1When It's Sleepy Time Down SouthLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLeon René & Otis René00:03:081942

-

2Trumpet Break And Ain't It The TruthLouis Armstrong and Studio OrchestraY.Harburg00:05:431942

-

3Theme & When It's Sleepy Timedown South, And CoquetteLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLeon René & Otis René00:03:291942

-

4InterviewLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJoy Dick00:01:411942

-

5I'Ve Got A Gal In KalamazooLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraMack Gordon00:03:441942

-

6Slender Tender And TallLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraMike Jackson00:02:531942

-

7Dear Old SouthlandLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraHenry Creamer00:03:041942

-

8Lazy RiverLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraHoagy Carmichael00:04:111942

-

9You Can'T Get Stuff In Your CuffLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJones00:03:481942

-

10Me And Brother BillLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLouis Armstrong00:03:081942

-

11On The Sunny Side Of The StreetLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraDorothy Fields00:04:251942

-

12Great Day And CoquetteLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraGus Kahn00:03:511942

-

13ShineLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraCecil Mack00:03:141942

-

14Lazy RiverLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraHoagy Carmichael00:04:071942

-

15Texte & One O'Clock JumpLouis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:07:081942

-

16Jubilee Theme Great Day & If I Could Be With YouLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraHenry Creamer00:04:581942

-

17Confessin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraAl Neiburg00:03:261942

-

18In The MoodLouis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:04:321942

-

19Texte I Can't Give You Anything But LoveLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraDorothy Fields00:05:061942

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1On The Sunny Side Of The StreetLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraDorothy Fields00:02:471943

-

2Back O'Town BluesLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLuis Russell00:03:431943

-

3As Time Goes ByLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraHerman Hupfeld00:03:061943

-

4Great Day Presentation & Leap FrogLouis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:04:561943

-

5Old Man MoseLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraZilner Randolph00:03:511943

-

6Ain'T MisbehavinLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraAndy Razaf00:04:561943

-

7Barrelhouse Bessie From Basin' StreetLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraH.Madigson00:03:331943

-

8The Peanut VendorLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraW.Gilbert00:04:511943

-

9Splender Tender & Tall And One O'Clock JumpLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraMike Jackson00:03:421943

-

10I Can'T Give You Anything But LoveLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraDorothy Fields00:03:121943

-

11Présentation & I Never KnewLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraTed Fio Rito00:02:461943

-

12What's A Good Word Mr BluebirdLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraInconnu00:03:121943

-

13I Lost My Sugar In Salt Lake CityLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJohnny Lange00:03:031943

-

14Lazy RiverLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraHoagy Carmichael00:03:261943

-

15Esquire BluesLouis Armstrong and Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street00:02:251944

-

16Basin' Street BluesLouis Armstrong and Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin StreetSpencer Williams00:03:441944

-

17Honeysuckle RoseLouis Armstrong and Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin StreetAndy Razaf00:02:031944

-

18Theme & Keep The Rhythm GoingLouis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:04:401940

-

19Confessin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraAl Neiburg00:03:121940

-

20Struttin' With Some Barbecue & ThemeLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLouis Armstrong00:03:321940

-

21Darling Nelly GrayLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraBenjamin Hanby00:02:491940

-

22Song Of The IslandLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraKing00:02:291940

INTEGRALE LOUIS AMSTRONG FA1360

THE COMPLETE LOUIS ARMSTRONG Vol.10

INTEGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG RADIO DAYS 1941-1944 & Compléments (Cotton Club 1940)

Direction : Daniel Nevers

DISQUE / DISC 1

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Frank GALBREATH, Shelton HEMPHILL, Gene PRINCE (tp) ; George WASHINGTON, Norman GREENE, Henderson CHAMBERS (tb) ; Rupert COLE, Carl FRYE (as) ; Prince ROBINSON (cl, ts) ; Joseph GARLAND (ts, bass sax, arr) ; Luis RUSSELL (p) ; Lawrence LUCIE (g) ; Hayes ALVIS (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm). Chicago, 16/11/1941

1. WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH (L.&O.René-C.Muse) (Decca F.8464/mx.93787-A) 3’09

2. LEAP FROG (J.Garland) (Decca F.8163/mx.93788-A) 2’57

3. I USED TO LOVE YOU (tk.A) (G.von Tilzer) (Decca 4106/mx.93789-A) 2’48

4. I USED TO LOVE YOU (tk.B) (G.von Tilzer) (Decca F.8163/mx.93789-B) 2’57

5. YOU RASCAL, YOU (S.Theard) (Decca F.8464/mx.93790-A) 2’57

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 1 à 5 / Personnel as for 1 to 5. Chicago (Grand Terrace Café), 16 & 27/11/1941

6. BASIN STREET BLUES (S.Williams) (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 3’04

7. EXACTLY LIKE YOU (J.McHugh-D.Fields) (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 3’52

8. PANAMA (W.H.Tyers) & Theme (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 3’16

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 1 à 5 / Personnel as for 1 to 5. Bernard FLOOD (tp), James WHITNEY (tb) & John SIMMONS (b) remplacent/replace G. PRINCE, N.GREENE & H. ALVIS. Culver City, CA (Casa Mañana), 1, 10 & 22/04/1942

9. Theme & SHINE (F.T.Dabney-J.Brown-C.Mack) (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 3’55

10. SHOE SHINE BOY (S.Cahn-S.Chaplin) (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 3’05

11. A ZOOT SUITE (Gilbert-O’Brian) (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 2’50

12. BASIN STREET BLUES (S.Williams) (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 3’09

13. YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT LOVE IS (D.Raye-G.DePaul) (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 4’44

14. BLUES IN THE NIGHT (H.Arlen-J.Mercer) (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 3’24

15. (Get Some)CASH FOR YOUR TRASH (T.W.Waller-E.Kirkeby) (Radio Aircheck - acetate) 3’02

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 9 à 15 / Personnel as for 9 to 15. Los Angeles, 17/04/1942

16. (Get Some)CASH FOR YOUR TRASH (T.W.Waller-E.Kirkeby) (Decca MU60272/mx.DLA 2974-A) 3’01

17. AMONG MY SOUVENIRS (tk.A) (Nichols-Leslie) (Decca BM4002/mx.DLA 2975-A) 2’44

18. AMONG MY SOUVENIRS (tk.B) (Nichols-Leslie) (Decca test/mx.DLA 2975-B) 2’30

19. COQUETTE (C.Lombardo-J.Green-G.Kahn) (Decca BM4002/mx.DLA 2976-A) 2’34

20. I NEVER KNEW (T.Fio Rito-G.Kahn) (Decca MU60272/mx.DLA 2977-A) 2’44

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 9 à 15 / Personnel as for 9 to 15. G.WASHINGTON (voc) ; plus Velma MIDDLETON (voc). Hollywood, 20/04/1942

21. SWINGIN’ ON NOTHING (Oliver-Moore) (RCM Prod. – Film soundtrack) 3’01

22. YOU RASCAL, YOU (S.Theard) (RCM Prod. – Film soundtrack) 2’55

23. SHINE (F.T.Dabney-J.Brown-C.Mack) (RCM Prod. – Film soundtrack) 2’34

DISQUE / DISC 2

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour plages 9 à 15, CD1 / Personnel as for tracks 9 to 15, CD 1. Hollywood, 20/04/1942

1. WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH (L.&O. René-C.Muse) (RCM Prod. – Film soundtrack) 3’05

LOUIS ARMSTRONG & the MGM Studio Orchestra

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) & grande formation / with large orchestra. Hollywood, 28/08/1942

2. TRUMPET BREAK & AIN’T IT THE TRUTH (H.Arlen-Y.Harburg) (MGM – Film soundtrack) 5’40

Á partir de la plage 3 du présent CD, les enregistrements sont en provenance de la radio militaire (AFN), réalisés en grande quantité dans les studios de la NBC à Los Angelès, entre les deux derniers mois de 1942 et le premier trimestre de 1943, sans plus de précisions. Ils ont été assemblés, à fin de diffusion, sur les transcriptions de l’AFRS (principalement dans les séries « Downbeat » et « Jubilee »). From this point, the next recordings included in this CD were made by and for the US military radio service (AFN) in the Los Angeles NBC studios, between the last two months of 1942 and the first three of 1943. They were then assembled on AFRS transcriptions for broadcasting (mainly in the“Downbeat”and“Jubilee”series).

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Prob. Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Frank GALBREATH, Shelton HEMPHILL, Bernard FLOOD (tp) ; James WHITNEY, Henderson CHAMBERS (tb) ; George WASHINGTON (tb, voc) ; Rupert COLE, Joe HAYMAN (as) ; Prince ROBINSON (cl, ts) ; Joe GARLAND (cl, ts, bar sax, arr) ; Luis RUSSELL (p) ; Lawrence LUCIE (g) ; Ted STURGIS (b) ; Henry “Chick” MORRISON (dm) ; Ann BAKER (voc) ; Dick JOY (mc). Los Angeles (NBC Studios)

3. Theme & WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH (Léon & Otis René-C.Muse) & COQUETTE (C.Lombardo-J.Green-G.Kahn) (AFRS “Downbeat” n°16 & 38) 3’28

4. INTERVIEW by Dick JOY (AFRS “Downbeat” n°16 & 38) 1’42

5. I’VE GOT A GAL IN KALAMAZOO (H.Warren-M.Gordon) (AFRS “Downbeat” n°16 & 38) 3’54

6. SLENDER, TENDER AND TALL (M.Jackson-H.Prince) (AFRS “Downbeat” n°16 & 38) 2’53

7. DEAR OLD SOUTHLAND (H.Creamer-T.Layton) (AFRS “Downbeat” n°16 & 38) 3’05

8. LAZY RIVER (H.Carmichael-S.Arodin) (AFRS “Downbeat” n°16 & 38) 4’11

9. YOU CAN’T GET STUFF IN YOUR CUFF (Jones-Williams) (AFRS “Downbeat” n°16 & 38) 3’50

10. ME AND BROTHER BILL (L.Armstrong) (AFRS “Downbeat” n°16 & 38) 3’08

11. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J.McHugh-D.Fields) & “Downbeat” Theme (AFRS “Downbeat” n°16 & 38) 4’22

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 3 à 11 / Personnel as for 3 to 11. Ernie “Bubbles” WHITMAN (mc). Los Angeles (NBC Studios)

12. “Jubilee” Theme GREAT DAY (V.Youmans) ; Presentation & COQUETTE (C.Lombardo-J.Green-G.Kahn) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°19) 3’52

13. SHINE (F.T.Dabney-J.Brown-C.Mack) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°19) 3’14

14. LAZY RIVER (H.Carmichael-S.Arodin) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°19) 4’10

15. Texte & ONE O’CLOCK JUMP (W.Basie) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°19) 7’05

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 3 à 11 / Personnel as for 3 to 11. Ernie “Bubbles” WHITMAN (mc). Los Angeles (NBC Studios)

16. “Jubilee” Theme GREAT DAY (V.Youmans) & IF I COULD BE WITH YOU (J.P.Johnson-H.Creamer); Presentation (AFRS “Jubilee”n°24) 4’58

17. CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°24) 3’26

18. IN THE MOOD (J.Garland) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°24) 4’35

19. Texte, I CAN’T GIVE YOU ANYTHING BUT LOVE (J.McHugh-D.Fields) & Theme (AFRS “Jubilee” n°24) 5’06

DISQUE / DISC 3

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Prob. Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Frank GALBREATH, Shelton HEMPHILL, Bernard FLOOD (tp) ; George WASHINGTON, James WHITNEY, Henderson CHAMBERS (tb) ; Rupert COLE, Joe HAYMAN (as) ; Prince ROBINSON (cl, ts) ; Joe GARLAND (ts, bar sax, arr) ; Luis RUSSELL (p) ; Lawrence LUCIE (g) ; Ted STURGIS (b) ; Henry “Chick” MORRISON (dm). Prob. Los Angeles, début/early 1943

1. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J.McHugh-D.Fields) (Radio Aircheck – AFRS ?) 2’44

2. BACK O’ TOWN BLUES (L.Armstrong-L.Russell) (Radio Aircheck – AFRS ?) 3’40

3. AS TIME GOES BY (L.Hupfield) (Radio Aircheck – AFRS ?) 3’03

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 1 à 3 / Personnel as for 1 to 3. Plus Velma MIDDLETON (voc) ; Ernie “Bubbles” WHITEMAN (mc). Los Angeles (NBC Studio), ca. 02-04/1943

4. “Jubilee” Theme : GREAT DAY (V.Youmans) ; Presentation & LEAP FROG (J.Garland) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°21) 4’56

5. OLD MAN MOSE (Z.Randolph-L.Armstrong) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°21) 3’49

6. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°26 & 58) 4’57

7. BARRELHOUSE BESSIE FROM BASIN STREET (H.Magidson-J.Styne) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°25 & 58) 3’33

8. THE PEANUT VENDOR (M.Simons-W.Gilbert-M.Sunshine) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°26 & 58) 4’50

9. SLENDER, TENDER AND TALL (M.Jackson-H.Prince) Texte & Theme ONE O’CLOCK JUMP (W.Basie) (AFRS “Jubilee n°58) 3’38

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA – Film “Jam Session”

Formation comme pour 1 à 3 / Personnel as for 1 to 3. Hollywood, 23/04/1943

10. I CAN’T GIVE YOU ANYTHING BUT LOVE (J.McHugh-D.Fields) (Columbia – Film Soundtrack) 3’08

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Prob.Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Shelton HEMPHILL, Frank GALBREATH, Bernard FLOOD (tp) ; George WASHINGTON, James WHITNEY, Henderson CHAMBERS (tb) ; Rupert COLE, Carl FRYE (as) ; Prince ROBINSON (cl, ts) ; ? Dexter GORDON (ts) ; Joe GARLAND (ts, bar sax) ; Gerald WIGGINS (p) ; Lawrence LUCIE (g) ; Art SIMMONS (b) ; Jesse PRICE (dm) ; Ann BAKER (voc). Dallas (Naval Air Station), ? 17/08/1943

11. Presentation & I NEVER KNEW (T.Fio Rito-G.Kahn) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°128) 2’45

12. WHAT’S A GOOD WORD, MR.BLUEBIRD ? (Anonymous) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°128) 3’10

13. I LOST MY SUGAR IN SALT LAKE CITY (L.René-J.Lange) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°128) 3’10 14. 14. LAZY RIVER (H.Carmichael-S.Arodin) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°128) 3’25

“CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY OF LOWER BASIN STREET”

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp,voc) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Coleman HAWKINS (ts) ; Art TATUM (p) ; Al CASEY (g) ; Oscar PETTIFORD (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm). New York City, 16/01/1944

15. ESQUIRE BLUES (L.Feather) (Radio NBC – Aircheck/acetate) 2’22

16. BASIN STREET BLUES (S.Williams) (Radio NBC – Aircheck/acetate) 3’42

Formation comme pour 15 & 16 / Personnel as for 15 & 16. Plus the “Woodbury Soap Symphony Orchestra” - Dir. Paul LAVAL, comprenant / including : A. Barnes RATTINA (tp) ; Milton CASSELL, Henry WADE, Rudolph ADLER, Alfie EVANS (saxes) ; Tony COLUCCI (g)… New York City, 16/01/1944

17. HONEYSUCKLE ROSE (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (Radio NBC – Aircheck/acetate) 2’00

1940 COMPLEMENTS : “COTTON CLUB” DATES…

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Shelton HEMPHILL, Bernard FLOOD, Henry “Red” ALLEN (tp) ; Wilbur de PARIS, George WASHINGTON, J.C. HIGGINBOTHAM (tb) ; Charlie HOLMES, Rupert COLE (cl, as) ; Bingie MADISON (cl, ts) ; Joe GARLAND (cl, ts, bar sax, arr) ; Luis RUSSELL (p, arr) ; Lee BLAIR (g) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm). New York City (“Cotton Club”), 24/03 & 9 & 15/04/1940

18. Theme & KEEP THE RHYTHM GOING (Radio Aircheck – acetate) 4’37

19. CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Doughterty-Reynolds) (Radio Aircheck – acetate) 3’08

20. STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE (L. & L.Armstrong) & Theme (Radio Aircheck – acetate) 3’30

21. DARLING NELLY GRAY (Harby) (Radio Aircheck – acetate) 2’47

22. SONG OF THE ISLAND (King) (Radio Aircheck – acetate) 2’29

LOUIS ARMSTRONG - volume 10

Voici le temps des assassins, son bruit, sa fureur, son cortège de larmes, de deuils… Manquait plus que ça… En fait, ce temps-là faisait déjà la pluie et le pas beau temps en Europe depuis un bail voire même deux. On ne sait plus exactement. Septembre 39 ? Oui, certes, mais bien avant sûrement. Septembre 39, c’est seulement le passage d’un état de déliquescence à un autre, la continuation de la politique par d’autres moyens, en somme. Ce que l’on peut aussi appeler trivialement « la guerre ». Futés, nos amis du continent d’en face comptaient bien s’en tirer à moindre mal, en filant au passage un petit coup de main (payant) à leurs ex-colonisateurs et en résorbant enfin complètement leur chômage (ce que le « new deal » n’avait pu faire), parce que l’Atlantique, quand même, ça faisait une sacrée étendue de liquide entre eux et les méchants ! Ils avaient oublié que, de l’autre côté du pays – alors qu’ils nous ont quand même pas mal bassiné avec leur conquête de l’Ouest – y a le Pacifique…

Moralité : entre la séance Decca et chicagoane de Louis Armstrong du 16 novembre 1941, par laquelle s’ouvre le présent recueil et celle, californienne (tiens, tiens…), du 17 avril 42 qui lui fait suite avant une longue interruption, il est arrivé un de ces légers évènements dont l’Histoire a du mal à se remettre même en éternuant très fort. Un incident, une bêtise, non point certes la mort d’une jument grise, mais bien le coulage presque intégral d’une flotte de guerre – passablement rouillée dit-on. Même que ça s’est passé du côté de Pearl Harbour le 7 décembre 41… Sûr que c’est pas la porte à côté, mais ça flanque tout de même un choc, parce qu’on est obligé de rompre des lances avec l’agresseur et que, du coup, les copains du dit agresseur se croient à leur tour dans l’obligation de vous déclarer la guerre. La loi de « l’Axe »… Soit dit en passant, ce fut bien la seule fois que le Reich numéroté trois déclara la guerre à quelqu’un. Jusqu’alors, c’était plutôt les autres (Angleterre, France) qui se chargeaient de la lui réclamer sur un plateau, ou bien on allait carrément s’installer en toute simplicité, ni vu ni connu, sans déclarer quoi que ce soit, chez le voisin. Tchécoslovaquie,Pologne, Hollande, Belgique, Danemark, Norvège, Grèce, Union Soviétique (entre autres) devinrent ainsi « terres d’accueil ». La mondialisation, déjà…

Et Louis Armstrong, tout nouveau et tout bouillonnant quadragénaire, dans tout ça ? A celle d’avant (« la der des ders »), en 17, on l’avait jugé trop jeune et on lui avait même déniché une faiblesse cardiaque. Peut-être celle qui finira par l’emporter pendant son sommeil bien plus tard… en 1971. 71 renversera toujours 17… Pour l’heure, quarante ans plus tôt, on le trouve déjà un poil trop vieux et, plutôt que de l’expédier résoudre les mystères de Midway ou lui faire faire de la saine culture physique à Okinawa, on préfère qu’il continue à travailler comme avant – dans le cadre de l’intendance, évidemment. Alors, Louis Armstrong continua à jouer dans les boîtes de tous les coins du pays, à participer à des tournages de films (portion congrue, comme d’habitude), et aussi à divertir les boys en partance pour Midway, Okinawa, la Normandie ou l’enfer, en chair, en os, en lèvres et surtout par la voie des ondes. Mais il ne fit guère de disques en ce temps-là. A cause de la grève des enregistrements destinés au commerce, qui dura plus de deux ans (août 42 – novembre 44). Ça ne pouvait tomber plus mal… Heureusement la radio était là. Elle y était, certes, depuis déjà belle lurette, mais cette fois c’était un peu différent : les radios commerciales, ces networks opulents, diffusant coast to coast avec des tas de sponsors pour leur tenir le micro passèrent au second plan. Ce coup-ci, la radio militaire, l’AFN (American Forces Network), prit le contrôle avec les moyens complètement indépendants de l’AFRS (American Forces Radio Service) : la radio de la Victoire d’où étaient bannies (en théorie) toutes sordides histoires de fric… Tout simplement l’apogée de la radio américaine, l’Âge d’Or : Radio Days – Woody Allen ne nous contredira certainement pas.

Ce sera bien évidemment la source principale des documents constituant le présent volume 10 ainsi que le suivant. Toutefois, il reste encore deux séances officielles avant le lourd silence imposé par le tout puissant patron du syndicat des musiciens américains, James Caesar Petrillo. Nous commencerons donc par y jeter un coup d’oreille…

Quatre titres à Chicago fin 41, quatre à Los Angeles au printemps 42, mêlant reprises, nouveautés et airs déjà anciens qu’Armstrong avait sûrement interprétés en leur temps, mais n’avait encore jamais enregistrés. On sait que depuis 1938-39, la maison Decca avait entrepris de faire refaire en version « moderne » quelques uns de ses chefs-d’œuvre de l’époque 1927-1932 comptant aussi parmi ses belles ventes (voir volumes 8 & 9 – FA 1358 & 1359). En fait, lors de sa brève période RCA-Victor (décembre 1932-avril 1933) on avait déjà essayé de l’aiguiller sur cette voie, mais il n’était pas resté assez longtemps. On l’a dit, dans le meilleur des cas, les nouvelles moutures sont sensiblement aussi bonnes que les anciennes – mais c’est loin d’être toujours le cas. Ainsi en est-il de You, Rascal You et de When It’s Sleepy Time Down South, malgré de belles interventions du trompettiste sur ce qui est son indicatif depuis maintenant une bonne décennie… I used to Love You pris sur tempo lent et Leap Frog sont du côté des nouveautés. Ce dernier morceau – dont ont trouvera une version radiophonique plus intéressante, captée en direct du « Cotton Club » en 1940 (hors chronologie), à la fin du CD 3 – porte la signature, en qualité de compositeur et arrangeur, du saxophoniste Joe Garland. En 1938, celui-ci, alors membre du big band du pianiste Edgar Hayes (dont faisait également partie le prometteur jeune batteur Kenny Clarke), avait déposé un autre morceau intitulé In the Mood, enregistré au départ chez Decca par cette sympathique formation (noire), et dont les droits conséquents assurèrent – on peut l’espérer – de confortables revenus à ses vieux jours, principalement grâce au petit coup de pouce (blanc) d’un certain Glenn Miller ! Il y aurait beaucoup à raconter à propos d’In the Mood (dont on goûtera une version radio ici même, sinon par Satchmo, du moins par son orchestre), notamment sur la genèse de son riff initial, attribuée à un nommé Armstrong Louis (cf Cornet Chop Suey), lequel en rendait responsable son Maître Oliver King…

Á propos de l’orchestre de Louis Armstrong, signalons qu’à partir de 1940, l’impresario glouton-gangster Joe Glaser, toujours soucieux de « rentabilité », chercha à éliminer plusieurs musiciens qui coûtaient vraiment trop cher ! Dans la charrette on fourra pêle-mêle les saxophonistes Charlie Holmes et Bingie Madison, le guitariste Lee Blair, le trompettiste Bernie Flood, les trombonistes Wilbur de Paris et George Washington, le bassiste « Pops » Foster et même le pianiste/directeur musical Luis Russell… Ils étaient parait-il trop vieux, ou trop petits, ou avaient mauvais caractère et refusaient de se parler… Grand temps donc de faire le ménage en recourant au sang neuf – et moins coûteux ! En réalité, tous ne furent pas virés d’un seul coup et l’opération s’étendit sur près de deux ans. Ainsi, Russell, bien que dégradé et remplacé à la direction par Garland, ne quitta qu’à la fin de 1942. Il avait cédé ses prérogatives de chef à Glaser. Les gars de l’orchestre ne le lui pardonnèrent jamais…

De février 1942 à mars 43, fit aussi son apparition une dame qui aurait du mal à passer inaperçue : l’opulente, la rondelette chanteuse/danseuse Velma Middleton, remplacée en1943-44 par Ann Baker, de retour du printemps 44 à celui de 1947,puis membre à part entière du All-Stars jusqu’à sa disparition en 1961… On l’entendra par deux fois dans le présent recueil. Louis Armstrong n’avait encore jamais cru devoir héberger une chanteuse dans son équipe : sans doute s’estimait-il, avec raison, suffisant dans le domaine vocal ! Mais l’univers du grand orchestre est impitoyable, même si l’on n’est pas à Dallas ! On peut bien se passer de remarquables musiciens comme les trop onéreux « Pops » Foster ou Charlie Holmes, mais pas d’une « indispensable » chanteuse. Également, parmi les jeunes stagiaires dans l’orchestre sur la Côte Ouest en 42, on relève le nom d’un bassiste du cru, un certain Charles Mingus, qui resta deux ou trois mois, mais ne semble pas avoir participé aux enregistrements.

La californienne séance Decca du 17 avril 42 s’inscrit dans le cadre d’une tournée dans l’Ouest, avec engagement de quatre semaines, à compter du 27 mars, à la « Casa Mañana » de Culver City. Cette fois, pas de reprise d’enregistrements anciens mais, outre le récent Cash for your Trash, deux « vieux » titres de la fin des années 1920, Among my Souvenirs et Coquette, ainsi qu’un thème légèrement plus jeune, I Never Knew. On l’a dit : d’éphémères petits « tubes » que Louis n’avait sûrement point manqué d’inscrire (brièvement) à son répertoire en ces temps révolus. Se souvient-on d’une version de Coquette, en 1928, par l’usine de Paul Whiteman, dans laquelle Bix Beiderbecke s’octroyait un délicat solo ? On aura noté que l’orchestre est au complet lors des deux séances, contrairement aux sessions précédentes, réalisées avec un groupe plus réduit, susceptible de sonner comme dans les versions originales des pièces anciennes. D’autre part, il existe des « prises alternées » pour I Used to Love You et Among my Souvenirs, ce qui, admettons-le, ne se révèle pas d’une importance capitale !

Outre les deux ultimes séances Decca de la période, il y eut aussi le retour au cinéma – par la petite porte, bien sûr. Les RCM Productions Inc. profitèrent de la présence de Louis du côté de Los Angeles au printemps 42 pour lui faire tourner le 20 avril, en compagnie de sa troupe, quatre courtes bandes ayant pour titres ceux des morceaux interprétés : You, Rascal You, When It’s Sleepy Time Down South et Shine – soit les « tubes » inévitables du répertoire depuis des lustres. Le premier et le dernier cités avaient même déjà connu les honneurs des salles obscures dès 1932, à l’occasion d’un court-métrage intitulé Rhapsody in Black and Blue et You, Rascal s’était également glissé dans un cartoon de Betty Boop (voir volume 6 – FA 1356). Dix ans après, les choses sont encore plus simples : ces petits films, probablement réalisés en 16m/m, étaient destinés à passer, dans les bistrots et autres boîtes, sur ces écrans que l’on appellera plus tard « scopitone »… Le quatrième de la série, Swingin’ on Nothing, n’a en revanche jamais fait l’objet du moindre enregistrement phonographique. Il est vrai qu’il n’est pas particulièrement extraordinaire, mais il permet d’entendre et de voir pour la première fois la dame mentionnée ci-dessus, Velma Middleton. Elle ne manque point de se livrer à une de ses coupables spécialités, le grand écart, mais là, avec uniquement la bande-son, il faudra faire un petit effort d’imagination. Le tromboniste George Washington lui donne et la réplique et Louis, habituellement si attentif à faire coïncider l’image avec le son dans la technique du play-back, se révèle légèrement largué à l’instant du solo. Mais pas question de refaire la prise !...

Dans le domaine des choses un peu plus sérieuses, Satch’, à l’été 42, fut aussi du tournage de la première comédie musicale MGM de Vincente Minelli (déjà chorégraphe du numéro Public Melody Number One d’Artists and Models en 1937 – voir volume 8 – FA 1358), Cabin in the Sky, entièrement interprété par des artistes noirs, comme jadis Hallelujah ou Green Pastures et, l’année suivante, Stormy Weather… Œuvre en définitive assez décevante, permettant toutefois d’apprécier quelques bons moments par Ethel Waters, Lena Horne et l’orchestre Duke Ellington. Quant à Louis qui ici appartient à la clique de Belzébuth, il arbore d’adorables petites cornes. Il aurait dû interpréter un long Ain’t It the Truth, flanqué d’une confortable formation de studio. Le morceau fut bel et bien enregistré, mais, finalement, supprimé au montage. On ne laissa subsister que deux, trois répliques et un court break de trompette, interrompu sur l’ordre d’un Satan, pas content du tout : « stop that noise ! »... Et dire qu’il s’en trouve encore pour penser que le jazz est la musique du Diable ! Le break en question est inclus au début de la plage 2 du CD 2, enchaîné sur la version intégrale de Ain’t It the Truth, telle qu’elle aurait dû sauter aux oreilles si… Dommage qu’on ait à peine le temps d’admirer les délicieuses cornes en tire-bouchon du facétieux diablotin.

L’année d’après, en avril 1943, Armstrong refit du cinéma, toujours à Hollywood, mais cette fois chez Columbia. Ce Jam Session fait partie de cette importante série de films que les grands studios (MGM, Fox, RKO, Warner, Universal, Paramount…) entreprirent entre 1942 et 1945 afin de participer à l’effort de guerre, en mettant à contribution leurs principales vedettes et en engageant des célébrités du spectacle, jazzmen noirs et blancs compris. Là Louis chante et joue I Can’t Give You Anything but Love. Pas de grande surprise, mais une séquence agréable. C’est ce qui comptait pour le public en ces heures-là…

Satchmo reviendra au cinéma en 1944… Mais d’abord, plat de résistance oblige : la radio, militaire ou non…

RADIO DAYS

Au commencement était le direct. On en fait toujours aujourd’hui… Un micro, un ampli, une antenne, les ondes indispensables, des gens qui parlent, chantent, jouent de la musique ou une pièce de théâtre…

Tout cela s’effiloche, s’évanouit dans l’air. Il n’en reste plus rien. Plus tard, on imprimera des programmes : à défaut de l’entendre soi-même, on sait ce que les « chers zauditeurs », heureux et encore rares possesseurs d’un poste de TSF, entendirent. On envie parfois leurs souvenirs fragiles.

Plus tard aussi, à partir des années 1920, on se mit à diffuser des disques du commerce, au grand dam des producteurs des dits disques qui firent interdire leur passage sur les ondes. Ça se fait toujours, mais les producteurs – enfin, leurs descendants – se sont calmés quand ils se sont rendus compte qu’en définitive tout cela était plutôt bon pour le commerce, en incitant les clients à acheter les galettes qu’ils venaient d’entendre…

A la fin de ces années 1920, les principaux réseaux se lancèrent dans la musique en conserve en faisant enregistrer leurs propres programmes, la plupart du temps dans les studios des firmes phonographiques (Brunswick/Vocalion, Victor, Columbia…) et dans les mêmes conditions que les disques du commerce. A ceci près que, sur ces 78 tours de trente centimètres de diamètre à étiquettes blanches (enchaînés à la diffusion), on incluait entre les morceaux la présentation, les petits sketchs et la publicité…

La décennie suivante correspond à la forte popularisation, tant en Amérique qu’en Europe, de la radio et à l’élargissement des techniques. L’arrivée du cinéma parlant avait facilité les choses. L’un des plus anciens systèmes utilisés consistait à enregistrer le son sur disque, puis à le synchroniser avec l’image. En France, Pathé, Gaumont, firent des démonstrations dès l’Exposition Universelle de 1900. Les Américains perfectionnèrent le procédé et l’exploitèrent sous le nom de “Vitaphone”. Dès lors, on reportait le son, après mixage, sur disques de quarante centimètres tournant à la vitesse de 33 tours, durant une douzaine de minutes – la durée d’une bobine de film 35m/m projeté à vingt-quatre images/seconde. Le système, fragile, peu fiable, fut abandonné après 1932-33, au profit du son optique, couché directement sur la même pellicule que l’image et lu sur le même appareil qu’elle. En revanche, l’usage des disques 33 tours de quarante centimètres se perpétua longtemps dans le monde de la radio. Rapidement, ceux-ci furent pressés, non plus dans la gomme-laque (shellac), mais dans une matière plastique ancêtre du vinyle. En réalité, on enregistrait en studio (ou parfois en concert) les différents éléments que l’on recopiait ensuite, en pratiquant un montage et un mixage, sur les disques en question que, pour cette raison, l’on appela « transcriptions » aux USA. Ces éléments réunis sur une même galette n’étaient pas nécessairement tous interprétés par le même artiste et pouvaient avoir été enregistrés à des dates assez éloignées les unes des autres. Ce qui explique qu’on ait souvent de grosses difficultés à dater précisément certaines de ces gravures des années 1943-46… Avant la guerre, les radios commerciales les plus en vue réalisaient elles-mêmes leurs propres transcriptions, utilisant souvent les studios des firmes phonographiques amies (par exemple RCA-Victor pour la NBC). Et ces choses en conserve pouvaient également être vendues aux petites stations locales ne disposant pas de production autonome. D’un autre côté, attirés par l’importance du marché en ces jours de crise, de nouveaux venus se mirent sur les rangs et proposèrent à leur tour des transcriptions clef en main aux très nombreuses radios indépendantes… En Europe aussi ce système connut un certain succès, mais c’est indéniablement en Amérique qu’en une trentaine d’années il récolta ses plus beaux fruits : des milliers, voire des millions de transcriptions en tous genres, encore mal recensées et connues aujourd’hui…

Quand la guerre éclata, la radio militaire n’eut qu’à reprendre à son compte cette pratique solidement établie et donner naissance aux innombrables suites de transcriptions de l’AFRS. Basé à Los Angeles, cet organisme n’en émettait pas moins sur tout le pays et s’attaquait à tous les genres, musicaux ou non. Certaines séries (quelques unes, nominatives, étaient dévolues à un seul artiste) eurent moins d’une dizaine de numéros, d’autres en comptèrent des centaines, notamment celles consacrées à la musique populaire américaine dont font partie blues et jazz. G.I. Jive, Yank Swing Session, Swingtime, Spotlight Bands, One Night Stand et surtout Downbeat et Jubilee, sont les noms de celles qui nous intéressent ici et que l’on retrouve le plus fréquemment dans la discographie. Les Jubilee, en particulier, faisaient la part belle aux interprètes noirs, musiciens, chanteurs, acteurs… Leur présentateur attitré fut dès le début (octobre 1942) Ernie « Bubbles » Whitman, comédien au bagout intarissable, auteur de plaisanteries pas toujours très fines mais souvent craquantes. Comme on tenait beaucoup à donner l’impression de concerts en direct, il remerciait un public fantôme, en vociférant, non pas « thank you, thank you », mais « hank you, hank you » ! Les curieux peuvent l’apercevoir au début du film d’Andrew Stone Stormy Weather (1943), jouant un Jim Europe très acceptable, censé diriger le Cake-Walk lors du retour des troupes de France, fin 1918… Il est toujours préférable de pouvoir mettre un visage sur une voix.

« Fantôme », le public, parce qu’en réalité, la plupart du temps tout cela, ces transcriptions – Jubilee comme Downbeat ou Yank Swing Session – étaient, on le sait, le résultat d’un assemblage : la musique captée à part en studio (et sans public), les commentaires (avec parfois, tout de même, quelques mots échangés avec l’artiste, pour faire vrai) mis en boîte séparément ailleurs à un autre moment et, par là dessus, les applaudissements, les rires, les sifflets, le tout savamment mixé… Du travail plutôt soigné, même si l’on décèle parfois les traces d’un montage un peu hâtif. Chaque face faisant une quinzaine de minutes, les programmes duraient en général une demie heure.

Afin que l’on se rende mieux compte de ce qu’était un programme complet, le CD 2 (plages 3 à 11) reproduit l’entièreté du Downbeat n°16 (identique au n°38), y compris le bout d’interview de Louis par Dick Joy et les chansons interprétées par l’orchestre et la chanteuse Ann Baker (Slender, Tender and Tall et You Can’t Get Stuff in your Cuff). Il s’agit-là en effet, assez exceptionnellement, d’une transcription presque intégralement consacrée à Armstrong, même lorsque celui-ci n’intervient pas directement, comme dans les deux pièces précitées. Pour la suite, on se limitera à ses seules interventions (parfois un unique morceau).

On sait à présent que presque toute la musique reportée sur ces grandes galettes fut, en réalité, enregistrée dans les studios de la NBC à Hollywood, de la fin de 1942 au printemps de 1943, tant par Louis que par les autres artistes invités. Sans doute y eut-il parfois de vraies captations en public, mais elles représentent l’exception confirmant la règle ! Pour le reste, le principe étant le même que pour les disques du commerce, on faisait souvent plusieurs « prises ». Puis les programmateurs sélectionnaient au fur et à mesure, sans trop se préoccuper de l’existence des dites « prises ». Ce qui explique que l’on peut trouver plusieurs moutures légèrement différentes (néanmoins enregistrées le même jour) de certains morceaux parmi les plus demandés sur des transcriptions appartenant à des séries différentes (Downbeat et Jubilee, par exemple), assemblées avec des compléments différents et diffusées à des mois d’intervalle !... Dans d’autres cas, il peut s’agir de la même prise ! Ainsi, le Coquette des Downbeat 16 et 38 (ici, plage 3 du CD 2) est-il différent de celui figurant sur le Jubilee 19, mais identique à celui du Jubilee 58. En revanche, Dear Old Southland et On the Sunny Side of the Street présentés sur les deux mêmes Downbeat (ici, plages 7 et 11), sont identiques à ceux inclus sur le Jubilee 21. Quant à Lazy River (plage 8), il s’agit là d’une prise différente de celle offerte sur les Jubilee 19, 26 et 49 !... Ces problèmes surviennent surtout à l’endroit des morceaux les plus souvent repris, parmi lesquels, pour ce qui touche Armstrong, on se doit de citer Coquette, Lazy River, On the Sunny Side of the Street, Shine et I Can’t Give You Anything but Love, particulièrement appréciés en ce temps-là. Mais des titres moins courus, comme I Got a Gal in Kalamazoo, One O’Clock Jump, Leap Frog, Old Man Mose, I Lost my Sugar in Salt Lake City ou Pistol Packin’ Mama, posent à peine moins d’interrogations. On se doute de la difficulté qu’il peut y avoir à démêler un tel écheveau si savamment entortillé. D’autant que le plus souvent, les seules indications fournies sur l’étiquette de ces disques se bornent à la mention de l’AFRS, au nom de la série et au numéro d’ordre dans la dite série ; pas le moindre titre ni nom(s) d’interprète(s). De bonnes âmes ont quelquefois ajouté à la main certaines de ces informations… Grâces, donc, soient rendues à l’oreille infaillible d’Irakli de Davrichewy et à son complice Jos Willems, infatigable fouineur à la recherche de toutes les grandes raretés armstrongiennes et auteur de la plus complète des discographies. Avec le paquet d’AFRS, si les dates d’assemblage et celles de diffusion sur les ondes sont parfois connues, celles des enregistrements restent le plus souvent mystérieuses. Disons qu’à partir de la plage 3 du CD2, l’on se retrouve presque toujours largué dans les ténèbres… Et cela devrait continuer dans le volume suivant !

Ce tableau de la radio étatsunienne plus ou moins militaire du début des années 1940 – soitpendant la guerre – serait incomplet si l’on n’y ajoutait les gravures effectuées directement par les auditeurs eux-mêmes, chez eux, depuis leur poste, sur des laques (mises au point à la fin des années 1920 par la firme française Pyrolac, détentrice du brevet pour le monde entier, USA compris), à l’aide d’un matériel des plus encombrant et fragile, de surcroît fort coûteux. Seuls les gens aisés pouvait se permettre ce genre de fantaisie, mais à en juger par la quantité de ces « airchecks » (ou « airshots ») répertoriés des deux côtés de l’Atlantique, ils étaient tout de même plus nombreux qu’on ne le pense et c’est tant mieux. Grâce à eux, une part des émissions transmises en direct se trouva préservée, aussi infime que puisse paraître semblable sauvetage. On a déjà croisé plusieurs exemples de cette technique d’amateur depuis les premiers, en Europe fin 1933 (voir volume 6 & suivants). Parmi les plus importants figurent l’émission de Martin Block d’octobre 38, avec Fats Waller et Jack Teagarden (volume 9 – FA 1359 : sur la disco du livret, la plage 11 du CD 1, Jeepers Creepers, a malencontreusement été omise, mais elle est bien inscrite au verso du boîtier), ainsi que le titre isolé, Harlem Stomp, en direct du Cotton Club fin 1939 et les trois acétates en piteux état d’octobre 41 inclus à la fin du CD 3.

Ici, on a ajouté, également en queue du CD 3, en « bonus » comme on dit – et hors chronologie, puisque tout ceci date de mars-avril 1940 – , cinq nouveaux titres retrouvés il y a peu, en provenance du « Cotton Club ». Keep the Rhythm Going, dans lequel Joe Garland prend un solo de saxophone basse, fait partie des pièces qu’Armstrong n’a point enregistrées commercialement, Darling Nelly Gray, connu dans la version intimiste avec les Mills Brothers, est cette fois interprété avec le big band en plutôt bonne forme, Song of the Islands délivre de superbes éclairs de trompette et Struttin’ with some Barbecue est proche de la version Decca de 1938… Les transmissions en direct du légendaire « Cotton Club » furentnombreuses entre 1937 et 1940, comme si les responsables de chaînes pressentaient qu’on approchait de la fin d’une époque… Duke Ellington fut tout particulièrement à l’honneur. Logique : Seigneur incontesté de l’établissement de 1927 à 1931, il lui devait une bonne part de sa gloire. N’empêche que sans les valeureux dévoreurs de laques embusqués derrière leur gros poste et leur drôle de machine (de gravure), tout cela, Duke, Louis et les autres, serait à jamais enfui depuis soixante-dix ans et plus… Le son, bien sûr, eu égard à la technique d’enregistrement et à la qualité de la réception parfois sur ondes courtes avec fading à la clef, ne peut prétendre rivaliser avec celui obtenu par les professionnels, mais on se doit de passer sur les défauts.

Ce que l’on devra faire encore davantage avec ces autres gravures de novembre 41 en provenance du « Grand Terrace » de Chicago (CD 1, plages 6 à 8) et celles piquées à la « Casa Mañana » de Culver City au printemps 42 (CD1, plages 9 à 15), quand Armstrong renouait avec le cinéma. Des trois titres chicagoans, on retiendra Panama, vieux thème néo orléanais par excellence, que Louis inclura durablement à son répertoire quelques années plus tard, mais qu’il n’avait pas enregistré jusqu’alors. La série californienne, plus abondante (sept titres sur la quinzaine récupérée), offre d’excellentes nouvelles versions de standards armstrongiens comme Shine (moins échevelé que par le passé), Shoe Shine Boy ou Basin Street Blues (même tempo que dans la mouture « Grand Terrace » 41). A Zoot Suit n’est qu’une chansonnette assez banale, mais Louis ne détestait nullement ce genre de morceaux. Il ne l’enregistra toutefois pas commercialement, non plus que You Don’t Know What Love Is, qui livre d’émouvantes interventions du trompettiste dans le cadre d’un bel et curieux arrangement. Cash for your Trash sera enregistré officiellement au cours de la dernière séance Decca (de même, d’ailleurs, que Coquette et I Never Knew, non retenus ici). Blues in the Night (d’Harold Arlen et Johnny Mercer) fut l’un des grands « tube » de l’an 42 : on se rappelle surtout la version de Jimmie Lunceford, mais il est vrai que, là non plus, il n’existe aucune édition commerciale de cette pièce par Satchmo – peut-être parce qu’ici, il ne fait que chanter.

Airshots encore, mais cette fois en date du 16 janvier 1944, soit deux jours avant l’inoubliable concert offert le soir du 18 au Metropolitan Opera de New York (et diffusé à la radio) par une bonne partie des lauréats du référendum des critiques organisé par la revue Esquire, à savoir Jack Teagarden, Coleman Hawkins, Art Tatum, Al Casey, Oscar Pettiford, Sidney Catlett, Roy Eldridge, Barney Bigard, Lionel Hampton, Red Norvo, Mildred Bailey, Billie Holiday, Teddy Wilson, Benny Goodman et, comme il se doit, Louis Armstrong… On reparlera dans le tome 11 de cette manifestation tout à fait exceptionnelle en rapport, bien entendu, avec la guerre. Louis étant loin d’intervenir sur tous les morceaux, pas question d’y rééditer de dit concert en entier. En revanche, il serait bon de le faire dans un recueil spécial où, de surcroît, l’on pourrait ajouter les titres où Satchmo ne joue pas, donnés deux jours plus tôt sur le réseau NBC dans le cadre de l’émission régulière (depuis 1940) intitulée Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street, conviant nombre de musiciens réputés mais parfois un poil oubliés, tel Jelly Roll Morton au crépuscule de sa vie. Ce 16 janvier 44, il s’agissait donc de faire la promo du concert et Louis se retrouve ainsi en compagnie des six premiers cités ci-dessus, sur trois morceaux, Basin Street Blues (obligatoire !), Esquire Blues (en référence à l’organisateur de la manifestation) et Honeysuckle Rose (en hommage à Fats Waller, disparu moins d’un mois plus tôt et qui avait récolté des voix)… Raretés dues, là encore, aux enregistreurs fous et magnifiques !...

Lesquels ne manquaient pas non plus d’ajouter à leur tableau de chasse les transmissions de l’AFRS. Là aussi ils firent bien, car nombre de celles-ci n’ont pu être récupérées et même leurs numéros sont inconnus. C’est par exemple le cas de trois titres, On the Sunny Side of the Street, Back O’Town Blues et As Time Goes By, placés en tête du CD3, sans doute un peu arbitrairement. Impossible de savoir d’où ils sortent ! Peut-être d’une transcription de la série Victory Parade of Spotlight Bands, peut-être celle portant le numéro 74 ? Mais peut-être pas ! Tant que l’on n’aura pas déniché un exemplaire du disque en question… Quoiqu’il en soit, on se trouve-là en présence de la plus ancienne version répertoriée de Back O’Town, qu’Armstrong conservera longtemps à son répertoire. Quant à As Time Goes By, chanson d’une pellicule oubliée qui avait fait un flop en 1931 et qui, recasée, fit un tabac douze ans après dans le Casablanca de Michael Curtiz (« Play it again, Sam », phrase que, d’ailleurs, Ingrid Bergman ne prononce jamais dans le film). Casablanca porte en effet le millésime 1943, ce qui laisse supposer que Louis et sa bande enregistrèrent l’aria ce printemps-là… Certes, ces airchecks, souvent bien conservés (l’émission du 16 janvier 44), sont aussi parfois dans un tel état de décomposition qu’il n’est guère possible de les inclure ici. Ainsi ce Spotlight Bands connu au moins sous trois références (225, 380 et un n°6 réservé à la Navy) : impossible d’en dégotter un seul exemplaire, alors que les laques léguées par un amateur sont atrocement pourries.

Moralité : nous n’entendrons pas ce Pistol Packin’ Mama de circonstances, puisque Armstrong n’en donna, semble-t-il, pas d’autre version – ce qui, avouons-le, n’a rien de gravissime.

Quant aux transcriptions – celles dont on dispose vraiment – on en trouvera la modulation, on l’a dit, à partir de la plage 3 du CD 2 : que commence la grande aventure... Outre les inévitables mais toujours agréables Lazy River, Coquette, ICGYABL, On the Sunny Side et plusieurs autres vieux crus (Ain’t Misbehavin’, Peanuts Vendor,Dear Old Southland, Shine, If I Could Be with You, Old Man Mose, Confessin’…), on y découvrira de petites choses éphémères, une Barrelhouse Bessie en droite ligne de Basin Street, une Petite nana de Kalamazoo, l’indispensable Frère Bill et le Susucre qu’on a laissé s’échapper à Salt Lake City… Des petites choses qu’on ne réentendra plus guère… Et puis, il y a aussi les curiosités comme In the Mood et One O’Clock Jump, des gageures en somme, dont on pouvait alors penser qu’elles ne dépasseraient pas deux ou trois diffusions radio. Mais elles sont restées et c’est bien. Preuve à l’appui que Louis Armstrong était toujours un Maître dans l’art de surprendre…

Daniel NEVERS

© 2011 Frémeaux & Associés – Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

LOUIS AMSTRONG - VOLUME 10

As Rimbaud said (in French of course), «Days of assassins, with all the noise and rage, grief, and a cortege of tears...» In fact, days like those had already been the outlook – rain and clouds – for some time in Europe, although no-one can remember precisely since when. There was September ‘39 of course, but it had definitely begun earlier. September ‘39 was merely a transit-period from one state of decay to another. You might say the politics were the same even if their means were different; it was a condition triflingly referred to as «War». Europe’s wily friends on the continent to the west were counting on getting through it all without too much harm: they’d be giving a hand (not entirely gratis) to their ex-colonists, and at the same time they’d be absorbing all their unemployment figures (the New Deal hadn’t succeeded at all). The Atlantic was just a lot of cold water separating them from baddies on the other side. What Americans seemed to have forgotten – surprisingly, after all that eyewash about conquering the Wild West Frontier – was that they themselves had another border, on the other side of their country, i.e. The Pacific...

The moral of the tale: between Louis Armstrong’s session for Decca in Chicago (November 16th 1941) and his Californian session (aha, now we‘re getting to it!) on April 17th 1942, which marks the start of this collection, there was an «event» of the kind from which History always recovers with difficulty, even after a huge sneeze. The event was a silly «incident» – less symbolic than the death of the grim reaper, granted – but nevertheless the moment when America’s finest warships were blasted into deep water at Pearl Harbour: December 7th 1941. While America wasn’t exactly Europe’s next-door neighbour, the sunken fleet still came as something of a shock, because once lances have been crossed with an aggressor, those friendly with the said aggressor suddenly find themselves obliged to declare war too (Axis oblige). It was also the only time that Reich N°3 had declared war on anybody: until then, others (France, England) had seen fit to demand heads on plates, or else go the whole hog and just invade their neighbours without any declaration at all. That, by the way, was how Czechoslovakia, Poland, Holland, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Greece and the USSR (amongst others) were transformed into «lands of welcome». Some welcome. It was globalization before its time...

And where did Louis Armstrong, a man in his Forties bubbling with ideas, fit into all this? For the previous (Great) war in ‘17, he’d been too young; they’d even detected a weak heart, maybe the same defect that finally carried him off during his sleep in 1971, which was a long time later. 71 always beat 17 backwards. But now, twenty-something years later, they thought he was already a bit too old and, rather than send him off to solve the mysteries of Midway, or do push-ups in Okinawa, they preferred him to continue his good work. Maybe they saw it as a kind of «support» role. Anyway, Louis Armstrong carried on blowing his horn in every club with a door, appearing in films (the meanest of roles, as per usual), and boosting morale amongst greenhorns and seasoned veterans alike, all of them on their way to Midway, Okinawa, Normandy, Hell or somewhere. And Louis played his role in the flesh, especially with his lips, and especially over the airwaves. He made hardly any records in those days, due to the musicians’ strike over record-royalties (a two-year hiatus from August ‘42 to November ‘44). The dispute couldn’t have come at a worse time but, thank God, there was still radio! Radio had been around for a long time – opulent networks broadcasting from coast to coast with a host of sponsors to keep them on the air – but this was different: all of a sudden, commercial stations had to take a back seat. Military radio was now the thing, and the AFN (American Forces Network), with all the independent resources of the AFRS (Armed Forces Radio Service) behind it, took control; this was about «sharing in Victory», and the AFN dispensed with the sordid question of money, in theory at least. It was «the Golden Age of Radio». Woody Allen (Radio Days) wouldn’t have it any other way. Radio, therefore, is obviously the main source of the music you can hear in this Volume 10 (and also the next). There remained, however, two official sessions before the studio-silence imposed by the all-powerful James Caesar Petrillo, the head of the American Federation of Musicians, and this is where we begin.

Those last commercial sessions produced four titles in Chicago at the end of 1941, plus four in Los Angeles in the spring of ‘42: a mix of new versions, new titles, and some old tunes which Armstrong had surely played before, but hadn’t yet recorded. It’s no secret that since 1938-39, Decca had been recording «modern» versions of some of Louis’ masterpieces from 1927-1932, which had also been some of his best-sellers (cf. Volumes 8 & 9 – FA 1358 & 1359). In fact, during his brief RCA-Victor period (December ‘32-April 1933), the label had already tried to point him in this direction, but he hadn’t stayed there for long enough. These new «covers», as we know, were in most cases just as good as Louis’ previous versions of them, but it wasn’t always the case, which goes for You Rascal You and When It’s Sleepy Time Down South, despite the trumpeter’s fine contributions on what had been his signature-tune for over a decade already... I Used To Love You taken at a slow tempo, and Leap Frog, were among the new tunes. That last piece – a more interesting radio-version of it recorded live from the Cotton Club in 1940 (out of chronological order) can be heard at the end of CD3 – carried the signature of composer/arranger/saxophonist Joe Garland. In 1938 Garland was in the big band of pianist Edgar Hayes (as was a promising young drummer named Kenny Clarke), and he registered another piece entitled In the Mood which was first recorded by Decca with Hayes’ nice (black) orchestra; its sizeable royalties ensured his comfort (at least, we hope so) for the rest of his days, mainly thanks to the boost it was given by a certain (white) bandleader named Glenn Miller. Much could be said about In the Mood – you can hear a radio version of it here, if not by Satchmo, at least by his orchestra – especially with regard to the genesis of its initial riff, attributed to a certain Armstrong, first name Louis (cf. Cornet Chop Suey), who said he owed it to his Master, namely a certain Oliver, first names Joe «King»...

On the subject of Louis Armstrong‘s orchestra, it’s useful to note that from 1940 onwards, the greedy-gangster-impresario Joe Glaser, always on the lookout for «profitability», tried to get rid of several musicians who were costing him too much: into the outgoing bus tumbled saxophonists Charlie Holmes and Bingie Madison, guitarist Lee Blair, trumpeter Bernie Flood, trombonists Wilbur de Paris and George Washington, bassist Pops Foster, even pianist/music-director Luis Russell… Apparently they were all too old or too small, bad-tempered, or just refusing to talk to each other... So it was high time the band was revamped with new blood – especially if it was cheaper! Actually, they weren’t all given the sack at the same time; the clean-up stretched over two years, with Russell (although demoted and replaced as band-director by Garland) the last to leave at the end of 1942. He handed his prerogatives as chief over to Glaser. The boys in the band never forgave him.

The period from February 1942 to March 1943 saw the appearance of a dame whose, well, appearance, didn’t exactly go unnoticed: the opulent, full figure of singer/dancer Velma Middleton graced the orchestra until Ann Baker replaced her momentarily in 1943/44; Velma came back (in the spring of ‘44), and stayed until the spring of ‘47, when she became a full-time member of the All-Stars until she died in 1961... You can hear Velma twice in this collection. The thought of having a singer join his crew had never crossed Armstrong‘s mind – perhaps because he thought, quite rightly, that his own vocal chords were quite sufficient – but the big-band universe knew no pity, even if it wasn’t the greedy, scheming «Dallas» which some made it out to be: it was OK to get rid of such remarkable musicians as the «too costly» Pops Foster or Charlie Holmes, but not an «indispensable» singer. Among the youngsters «gaining work experience» in the band out on the West Coast in 1942, you might also note the name of a certain Charles Mingus on bass; he stayed two or three months, but doesn’t seem to have been on any of the group’s records.

Louis’ California session on April 17th 1942 came during a tour out on the coast, while the trumpeter was enjoying a four-week gig (starting on March 27th) at the Casa Mañana in Culver City. There were no «covers» of old recordings this time but, apart from the recent Cash for your Trash, there were two «old» titles from the end of the Twenties, Among my Souvenirs and Coquette, plus a slightly younger tune, I Never Knew. As we said above, these were some of the ephemeral little hits that Louis surely hadn’t missed putting in his book during the old days. Does anyone remember the 1928 version of Coquette by the Paul Whiteman factory? With Bix Beiderbecke‘s fine solo on it? The band was complete for both sessions, unlike the previous dates, which featured a downsized group that was supposed to have a sound more like the original versions of the older tunes. Alternate takes also exist for I Used to Love You and Among my Souvenirs, which, you have to admit, shouldn’t cause anyone to lose much sleep.

Apart from the period’s last two sessions for Decca, there were also films – to which Louis returned via the tradesman’s entrance so to speak. RCM Productions Inc. took advantage of Louis’ presence near LA in spring 1942 and filmed him on April 20th with his troupe. These short-films carried the names of the tunes Louis played: You Rascal You, When It’s Sleepy Time Down South and Shine were inevitable hits that had been in Louis’ book for ages; the first and last-mentioned tunes had already been honoured in darkened theatres as early as 1932, thanks to a short-film entitled Rhapsody in Black and Blue, and You Rascal You had been slipped into a Betty Boop cartoon (cf. Vol.6 – FA 1356). Things were simpler ten years later: these little films, probably shot with a 16mm camera, were aimed at bars and clubs with the kind of screen-equipped jukeboxes they later called Scopitones… On the other hand, the fourth in the series, Swingin’ on Nothing, had never been featured on any recording. True, it isn’t extraordinary, but it does allow you to hear (and see), for the very first time, the lady mentioned above, i.e. Velma Middleton. She also executes one of the specialities to which she pleaded guilty – the splits – but here you’ll need to use your imagination (all soundtrack, no picture...) Trombonist George Washington swaps phrases with her, and Louis, who usually took so much care over adding sound to a picture using the playback technique, appears to be slightly left behind when the solo comes in. But there was no chance of a second take!

More seriously, summer 1942 saw Satch’ make an appearance in Vincente Minnelli’s first musical for MGM – after his choreography for the Public Melody Number One number in 1937’s Artists and Models (cf. Vol.8 – FA 1358) –, the film called Cabin in the Sky, which featured only black artists, as had Hallelujah or Green Pastures earlier, or Stormy Weather the following year. It was rather disappointing from a film-critic’s viewpoint, but it does give filmgoers a chance to appreciate a few good moments from Ethel Waters, Lena Horne and the Duke Ellington Orchestra. As for Louis, who belongs to the clan of the demon Beelzebub, he wears a lovely pair of horns in the movie. He should have been seen playing a lengthy version of Ain’t It the Truth, flanked by a comfortable studio-band. The piece was actually recorded, but the scene was removed during the editing, the only remains being two or three rejoinders and a short trumpet-break interrupted at the command of a Satan who wasn’t happy at all: «Stop that noise!«... Talk about those who still think jazz is the Devil’s music! The break in question is included at the beginning of Track 2 on CD2, shunted with the entire version of Ain’t It the Truth as it would have jumped out at people’s ears if...etc. And it’s also a pity that Louis was onscreen barely long enough for fans to admire the little devil’s delightful corkscrew-horns.

A year later (April ‘43) Armstrong did another film, also in Hollywood but this time for Columbia. Jam Session belongs to the major series of films undertaken by the great studios (MGM, Fox, RKO, Warner, Universal, Paramount…) between 1942 and 1945 as part of the war effort: they put their biggest stars into these productions and also hired showbiz celebrities including jazzmen both black and white. In Jam Session Louis sings and plays I Can’t Give You Anything but Love. There are no surprises, but it’s a pleasant scene, and that’s what counted in those troubled times. Satchmo would return to movies in 1944 but, first, the main course: radio, both in uniform and the civilian kind.

RADIO DAYS

In the beginning, there was live radio – still up and running today – and it involved microphones, amplifiers, aerials, indispensable airwaves, and people talking, singing, playing music and/or acting... and then it all unravelled into thin air before promptly disappearing. There’s nothing left. Later, they had printed schedules, and people who couldn’t hear whatever followed the phrase, «And now you’re going to hear...» (at the time the announcer actually said it on the radio) could check the small print and find out what was played. Sometimes we envy those fragile memories... Later, too – beginning in the Twenties – radio began airing commercial records, to the dismay of the producers of the aforesaid records, who promptly banned them from being played on radio. That still happens, but record-producers – or rather their descendants – calmed down when they realized that it was actually rather good for business: after all, it encouraged listeners to go out and buy the records. At the end of those Twenties, the most important networks jumped on the bandwagon and began recording their own programmes, most often in studios that belonged to record-companies (Brunswick/Vocalion, Victor, Columbia…), and most often in conditions that were the same as for commercial recordings. The only difference was that these 12» 78rpm records with a white label (made available to coincide with the broadcasts) contained other things in between the music-tracks: announcements, sketches, advertisements…

The next decade corresponded to a strong increase in the popularity of radio, in both America and Europe, and also the development of new techniques. The arrival of talking pictures had made it all easier. One of the oldest systems used consisted in recording the sound onto disc, and then synchronizing it with the picture. In France, Pathé and Gaumont had demonstrated how they did it during the 1900 Universal Exhibition. The Americans perfected the process and exploited it as «Vitaphone». From then on, the sound, once mixed, was transferred onto 16»-diameter discs which spun at 33? rpm and lasted a dozen minutes – the length of a reel of 35mm film projected at 24 frames-per-second. That system, which was fragile and rather unreliable, was abandoned after 1932-33 in favour of optical sound, which was layered directly onto the same film as the picture, and read by the same projector. But the use of 16» discs was perpetuated for a long time in radio. They were quickly pressed, no longer using shellac, but rather using a plastic material that was the ancestor of vinyl. In reality, the various elements were recorded in a studio (or sometimes at a concert) and later copied/electrically transcribed – after the editing & mixing processes – onto the records in question; which is why the discs were called «transcriptions». The various elements recorded onto a single disc weren’t all necessarily by the same artist, nor were they all recorded at the same time (the dates could even be quite far apart), which explains why it’s sometimes so difficult to put a precise date to some of the recordings made between 1943 and 1946. Before the war, the biggest commercial stations did their own transcriptions, often using the recording-studios of friendly labels (NBC went to RCA-Victor for example). Transcription-facilities were also sold to smaller local stations without their own production-system. The other side of the coin was that newcomers – attracted by the importance of the market in those times of crisis – joined in by offering ready-made transcriptions to numerous independent stations... The system was also something of a success in Europe, but nobody could deny that the largest crop was produced in America, where thousands of these transcriptions, maybe a million, were manufactured in the space of thirty years, most of them little-known – and many unlisted – even today.

When war broke out, army radio had only to adopt this solidly established practice to give birth to the countless series of AFRS transcriptions. Even though based in Los Angeles, the AFRS transmitted all over the country, tackling all kinds of genre, musical or not. Some of their transcriptions – among them ones with names, devoted to a single artist – had fewer than ten titles per series, while others had hundreds, particularly those devoted to American popular music, including blues and jazz. G.I. Jive, Yank Swing Session, Swingtime, Spotlight Bands, One Night Stand, and Downbeat and Jubilee especially, were the names given to transcriptions of great interest to us here, and these are also the ones most often found in the discographies. The Jubilee recordings in particular included many black artists, musicians, singers, actors... Right from the beginning in October ‘42, their regular presenter was Ernie «Bubbles» Whitman, a comic with a spiel that never ran dry, and whose gags, while not always elegant, were often very funny. The aim was to give the impression that these were live concerts, and so Ernie would thank a ghost audience by saying, not «Thank you, thank you!», but «Hank you, hank you!», and if you’re curious you can get a glimpse of him at the beginning of Andrew Stone’s film Stormy Weather (1943), where he plays a quite acceptable Jim Europe supposedly conducting the Cake-Walk during the troops‘ return from France in 1918... It’s always better to put a face to a voice. Ernie had a «ghost» audience because, in reality, these transcriptions – Jubilee, Downbeat or Yank Swing Session – were most often «assembled»: the music went down in a studio (without an audience); the commentary (sometimes, it’s true, containing a few words with the artist, to make it all seem more «real») was recorded somewhere else at some other time; and they overlaid the applause, laughter and whistles after skilfully mixing it all together. The job was meticulous, even if you could sometimes detect traces of hasty editing. With each side taking up fifteen minutes, the programmes generally lasted half an hour.

In order to give you an idea of what a complete programme might be, CD2 (Tracks 3 to 11) reproduces the entire programme of Downbeat N°16 (identical to N°38), complete with a bit of the interview Louis gave to Dick Joy and the songs performed by the orchestra behind singer Ann Baker (Slender, Tender and Tall and You Can’t Get Stuff in your Cuff). This programme – something of an exception – is a transcription almost entirely devoted to Armstrong, even when Louis isn’t a direct contributor, which is the case for the two titles just mentioned. The others contain only Louis’ contributions (sometimes a single tune).