- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

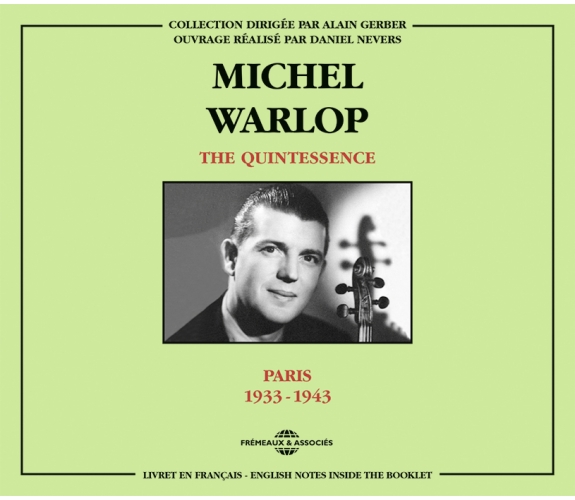

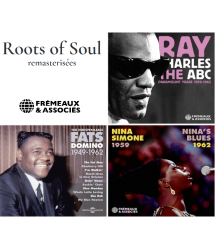

PARIS - 1933-1943

MICHEL WARLOP

Ref.: FA295

Direction Artistique : DANIEL NEVERS

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 2 heures 17 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

PARIS - 1933-1943

« Il y avait un étrange personnage, pâle, aux yeux délavés, qui jouait du violon. (…) Cet être diaphane qui semblait venu d’un autre monde et prêt à y retourner était Michel Warlop (…). Quand il a joué, je n’ai pas compris grand’ chose mais j’ai senti une certaine grandeur dans sa musique, quelque chose, qui me dépassait. »

Guy LAFITTE, saxophoniste

Les coffrets « The Quintessence » jazz et blues, reconnus pour leur qualité dans le monde entier, font l’objet des meilleurs transferts analogiques à partir des disques sources, et d’une restauration numérique utilisant les technologies les plus sophistiquées sans jamais recourir à une modification du son d’origine qui nuirait à l’exhaustivité des informations sonores, à la dynamique et la cohérence de l’acoustique, et à l’authenticité de l’enregistrement original.

Chaque ouvrage sonore de la marque « Frémeaux & Associés » est accompagné d’un livret explicatif en langue française et d’un certificat de garantie.

“Joe Venuti and Eddie South, Stuff Smith and Stéphane Grappelli, even Sven Asmussen: all of them long gone, but not forgotten. All are deservedly remembered as the greatest violinists to play so-called “classic” jazz, and so the most famous. Hardly anyone remembers Michel Warlop, and that's most unfair.”

Daniel Nevers

Frémeaux & Associés’ « Quintessence » products have undergone an analogical and digital restoration process which is recognized throughout the world. Each 2 CD set edition includes liner notes in English as well as a guarantee. This 2 CD set presents a selection of the best recordings by Michel Warlop between 1933 and 1943.

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : Daniel Nevers EN ACCORD AVEC ALAIN GERBER DANS LA COLLECTION THE QUINTESSENCE.

DROITS : DP / FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

CD 1 (PARIS, 1933-1941) : GRÉGOR & SES GRÉGORIENS FANTAISIE GRÉGORIENNE. L’ORCH. Jazz “CHICAGO SYNCOPATORS” MY GAL SAL - HARLEM HURRICANE. MICHEL WARLOP & SON ORCH. ALL FOR THE SWING • CRAZY FIDDLE. LÉON KARTUN & SON ORCH. KNICK KNACK BLUES. ORCH. ANONYME / ANONYMOUS ORCHESTRA Dr. SWING. MICHEL WARLOP & SON ORCH. DE JAZZ MISS OTIS REGRETTE. MICHEL WARLOP & SON ORCH. STRANGE HARMONY • SÉRÉNADE • ÇA ME TRACASSE (Double Trouble). MICHEL WARLOP & SON ORCH. LITTLE GIRL BLUE • RHYTHM STEP. ORCHESTRE (sic !) DÉSESPÉRANCE • DOUX SOUVENIR. MICHEL WARLOP & SON ORCH. & D. REINHARDT TAJ MAHAL. M. WARLOP, D. REINHARDT, S. GRAPPELLI, L. VOLA SWEET SUE (JUST YOU). ANDRÉ CLAVEAU, av. MICHEL WARLOP & ORCH. JE VEUX CE SOIR. JEAN TRANCHANT, av. MICHEL WARLOP & ORCH. MAIS J’ATTENDS. MICHEL WARLOP & SON ORCH. RETOUR • NANDETTE. MICHEL WARLOP & SON SEPTUOR Á CORDES KERMESSE • AISÉMENT.

CD 2 (PARIS, 1941-1943) : MICHEL WARLOP & SON SEPTUOR Á CORDES TEMPÊTE SUR LES CORDES • HARMONIQUES. LE JAZZ DIXIT – Dir. RAYMOND LEGRAND STRICTEMENT POUR LES PERSANS • SAUT D’UNE HEURE (One O’Clock Jump). GUY PAQUINET & SON ORCH. FUMÉES • IDA. MICHEL WARLOP & L’ORCH. SYMPHONIQUE JAZZ DE PARIS – Dir. R. BERGMANN SWING CONCERTO I & II. MICHEL WARLOP & SON SEPTUOR Á CORDES NITE • SUR QUATRE CORDES • POKER • MI LA RÉ SOL. MICHEL WARLOP & SES 15 SOLISTES DE JAZZ KIBOULA • MODERNISTIC. LES CHANTERELLES, acc. par MICHEL WARLOP & SON ORCH. C’EST DU RYTHME. PIERRE MINGAND, acc. par MICHEL WARLOP & SON ORCH. SI TU ME DIS OUI. MICHEL WARLOP & SON SEPTUOR Á CORDES OUI • CHRISTIANA • CHROMATIQUES • MICKEY. MICHEL WARLOP & SON ENSEMBLE MICHOU • LOUBI • PRISE DE COURANT • ELYANE.

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Fantaisie grégorienneMichel Warlop, Grégor et ses Grégoriens00:03:181933

-

2My gal salMichel Warlop, Orchestre Chicago syncopators00:02:461933

-

3Harlem hurricaneMichel Warlop, Orchestre Chicago syncopators00:02:301933

-

4All for the swingMichel Warlop et son Orchestre00:02:351934

-

5Crazy fiddleMichel Warlop et son Orchestre00:03:021934

-

6Knick knack bluesMichel Warlop, Léon Kartun et son Orchestre00:02:551934

-

7Dr swingMichel Warlop et Orchestre anonyme00:03:041934

-

8Miss Otis regretteMichel Warlop et son OrchestreLouis Hennevé00:03:031935

-

9Strange harmonyMichel Warlop et son Orchestre00:02:381935

-

10SerenadeMichel Warlop et son Orchestre00:02:511935

-

11Ca me tracasseMichel Warlop et son OrchestreR. Raingé00:02:351935

-

12Little girl blueMichel Warlop et son Orchestre00:03:031936

-

13Rhythm stepMichel Warlop et son Orchestre00:02:421936

-

14DésespéranceMichel Warlop et son OrchestrePierre Zeppelli00:03:031937

-

15Doux souvenirMichel Warlop et son OrchestrePierre Zeppelli00:03:051937

-

16Taj MahalMichel Warlop et son Orchestre, Django Reinhardt00:03:221937

-

17Sweet sueMichel Warlop, Django Reinhardt, Stéphane Grappelli, L. VolaW. Harris00:02:341937

-

18Je veux ce soirMichel Warlop et son Orchestre, André ClaveauGranier00:03:151937

-

19Mais j'attendsMichel Warlop et son Orchestre, Jean TranchantGranier00:02:541938

-

20RetourMichel Warlop et son Orchestre00:02:381941

-

21NandetteMichel Warlop et son Orchestre00:03:001941

-

22KermesseMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:02:401941

-

23AisémentMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:02:581941

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Tempête sur les cordesMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:02:361941

-

2HarmoniquesMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:03:061941

-

3Strictement pour les persansMichel Warlop, Le Jazz dixit, Raymond Legrand00:02:441941

-

4Saut d'une heureMichel Warlop, Le Jazz dixit, Raymond Legrand00:03:271941

-

5FuméesMichel Warlop, Guy Paquinet et son Orchestre00:02:481941

-

6IdaMichel Warlop, Guy Paquinet et son Orchestre00:03:001941

-

7Swing concerto I et IIMichel Warlop et l'Orchestre symphonique Jazz de Paris, R. Bergmann00:07:401942

-

8NiteMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:02:451942

-

9Sur quatre cordesMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:02:271942

-

10PokerMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:02:431942

-

11Mi la re solMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:02:421942

-

12KiboulaMichel Warlop et ses 15 solistes de jazz00:02:561942

-

13ModernisticMichel Warlop et ses 15 solistes de jazz00:03:171942

-

14C'est du rythmeMichel Warlop et son orchestre, Les ChanterellesM. Erlange00:02:281942

-

15Si tu me dis ouiMichel Warlop et son Orchestre, Pierre MingandL. Gasté00:03:041943

-

16OuiMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordesL. Gasté00:02:511943

-

17ChristianaMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:02:491943

-

18ChromatiquesMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:02:331943

-

19MickeyMichel Warlop et son septuor à cordes00:03:021943

-

20MichouMichel Warlop et son ensemble00:02:591943

-

21LoubiMichel Warlop et son ensemble00:03:241943

-

22Prise de courantMichel Warlop et son ensemble00:02:231943

-

23ElyaneMichel Warlop et son ensemble00:03:051943

Michel Warlop FA295

COLLECTION DIRIGÉE PAR ALAIN GERBER

OUVRAGE RÉALISÉ PAR DANIEL NEVERS

MICHEL WARLOP

THE QUINTESSENCE

PARIS 1933-1943

DISCOGRAPHIE / DISCOGRAPHY

CD 1 (1933-1941)

1. FANTAISIE GRÉGORIENNE (M.Warlop) (Ultraphone AP 1009/mx.P 76371) 3’14

GRÉGOR ET SES GRÉGORIENS : Gaston LAPEYRONNIE (tp)?; Pierre ALLIER (tp solo)?; Jean NAUDIN, Vladimir… (tb)?; André EKYAN, Roger FISBACH ou/or Georges THARAUD (as)?; André LAMORY (as, ts)?; Alix COMBELLE (ts)?; Roger ALLIER (bars)?; Michel WARLOP (vln, arr)?; Stéphane GRAPPELLI ou/or Michel EMER (p)?; Emile FELDMAN (g)?; Roger “Toto” GRASSET (b)?; … McGREGOR (dm)?; Grégor (Krikor KELEKIAN) (dir). PARIS, ca. 20-25/03/1933.

2. MY GAL SAL (H.McKnight) (Sonabel HM 238/mx.1764-SK) 2’42

3. HARLEM HURRICANE (H.McKnight) (H.Mateo HM 243/mx. 616) 2’26

L’orchestre jazz “Chicago Syncopators” – Refrain de Violon Hot exécuté par Michel WARLOP : André PICO, ? Pierre ALLIER (tp)?; ? Guy PAQUINET (tb)?; Georges THARAUD ou/Or Roger FISBACH (as)?; André LAMORY (as, ts, cl)?; Georges JACQUEMONT-BROWN(ts)?; Roger ALLIER (bars)?; Michel WARLOP (vln)?; Lucien MORAWECK (p, arr)?; Roger GRASSET (b)?; ? Max ELLOY (dm). PARIS, ca. Nov. 1933.

4. ALL FOR THE SWING (M.Warlop) (Gramophone K-7218/mx.0PD 7-1) 2’32

5. CRAZY FIDDLE (M.Warlop) (Gramophone K-7218/mx.0PD 10-1) 3’00

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON ORCHESTRE : Noël CHIBOUST (tp)?; Roger FISBACH, André LAMORY (as)?; Alix COMBELLE (ts)?; Michel WARLOP (vln, arr, ldr)?; Lucien MORAWECK (p)?; Edmond MASSÉ (g)?; Roger GRASSET (b)?; … McGREGOR (dm). PARIS, 8/01/1934.

6. KNICK KNACK BLUES (J.Wiéner) (Echo 113/mx. 517) 2’51

LÉON KARTUN ET SON ORCHESTRE : Faustin JEANJEAN, ? Gaston LAPEYRONNIE (tp)?; ? Isidore BASSART (tb)?; Maurice JEANJEAN (cl, as)?; ? Edmond COHANIER (ts)?; Roger ALLIER (bars)?; Michel WARLOP (vln solo)?; ? Stéphane GRAPPELLI, Sylvio SCHMIDT (vln)?; Lucien MORAWECK (p)?; ? Edmond MASSÉ (g)?; Non Identifiés/Unidentified tuba, b & dm?; Jacques MÉTÉHEN (arr)?; Léon KARTUN (dir). PARIS, ca. Jan. 1934.

7. Dr. SWING (Inconnu/Unknown) (Test / mx. 1089) 3’01

ANONYMOUS ORCH. : tp, 2as, ts, Michel WARLOP (vln), p, g, b, dm (prob. P. ALLIER, LAMORY, Alain ROMANS…). PARIS, 1934.

8. MISS OTIS REGRETTE (C.Porter-L.Hennevé-L.Palex) (Gramophone K-7444/mx.0LA 316-1) 3’00

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON ORCHESTRE DE JAZZ : Pierre ALLIER, Maurice MOUFLARD, Noël CHIBOUST (tp)?; Marcel DUMONT, Isidore BASSART (tb)?; André EKYAN, Amédée CHARLES (as)?; Alix COMBELLE (ts, cl); Charles LISÉE (bars,as)?; Alain ROMANS (p)?; Roger CHAPUT (g)?; Roger GRASSET (b)?; Maurice CHAILLOU (dm)?; Michel WARLOP (voc, arr, ldr). PARIS, 6/02/1935.

9. STRANGE HARMONY (M.Warlop) (Gramophone K-7633/mx.0LA 749-1) 2’34

10. SÉRÉNADE (M.Warlop) (Gramophone K-7633/mx.0LA 751-1) 2’48

11. ÇA ME TRACASSE (Double Trouble) (R.A.Whiting-R.Rainger-L.Robin)

(Gramophone K-7718/mx.0LA 752-1) 2’31

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON ORCHESTRE : Michel WARLOP (vln, arr)?; Louis RICHARDET (accord)?; Jean “Matelo” FERRET, Etienne “Sarane” FERRET, Jean MAILLE (g)?; Jean STORNE (b). PARIS, 5/12/1935.

12. LITTLE GIRL BLUE (R.Rodgers) (Gramophone K-7674/mx.0LA 993-1) 3’00

13. RHYTHM STEP (R.Metzger) (Gramophone K-7674/mx.0LA 995-1) 2”38

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON ORCHESTRE : Maurice MOUFLARD, Pierre ALLIER, Alex RENARD (tp)?; Marcel DUMONT, Guy PAQUINET (tb)?; André EKYAN (as, cl)?; Charles LISÉE (as, bars)?; Amédée CHARLES (as)?; Maurice CIZERON (ts, fl)?; Michel WARLOP (vln, arr, ldr)?; Alain ROMANS (p)?; Jean MAILLE (g)?; Jean STORNE (b)?; Maurice CHAILLOU (dm). PARIS, 18/03/1936.

14. DÉSESPÉRANCE (M.Warlop-P.Zeppilli) (Polydor 514400/mx.3431hpp) 3’00

15. DOUX SOUVENIR (M.Warlop-P.Zeppilli) (Polydor 514400/mx.3432hpp) 3’02

ORCHESTRE (sic) : Jean MAGNIEN (fl, cl, as, ts)?; André LAMORY (as)?; Michel WARLOP (vln)?; Pierre ZEPPILLI (p)?; Joseph REINHARDT (g solo), ? Eugène VÉES (g)?; ? Louis VOLA (b)?; Georges PAQUAY (dm, fl). PARIS, 3-4/06/1937.

16. TAJ MAHAL (M.Warlop) (Swing 28/mx. 0LA 2000-1) 3’20

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON ORCHESTRE : André PICO (tp)?; André LAMORY (as, cl)?; Jean MAGNIEN (as, fl)?; Georges PAQUAY (fl)?; Charles SCHAAF (ts, cl)?; Michel WARLOP (vln, arr, ldr)?; Pierre ZEPPILLI (p)?; Django REINHARDT (g)?; Louis VOLA (b). PARIS, 21/12/1937.

17. SWEET SUE (JUST YOU) (V.Young-W.Harris) (Swing 43/mx.0LA 2312-1) 2’31

MICHEL WARLOP, solo de violon. Acc. par/by : Stéphane GRAPPELLI (p)?; Django REINHARDT (g)?; Louis VOLA (b). PARIS, 28/12/1937.

18. JE VEUX CE SOIR (Zeppilli-Granier-Vital) (Gramophone K-8120/mx.0LA 2489-1) 3’11

ANDRÉ CLAVEAU, acc. par MICHEL WARLOP et son orchestre. André CLAVEAU (chant/voc) acc. par/by : André LAMORY (as)?; Jean MAGNIEN (as, fl)?; Georges PAQUAY (fl, dm)?; Michel WARLOP (vln)?; Pierre ZEPPILLI (p)?; ? Eugène VEES (g)?; Louis VOLA (b). PARIS, 18/03/1938.

19. MAIS J’ATTENDS (J.Tranchant) (Pathé PA-1577/mx.CPT 4036-1) 2’51

JEAN TRANCHANT, acc. par MICHEL WARLOP et son orchestre. Jean TRANCHANT (chant/voc) acc. par les mêmes musiciens que pour 18 / by the same personnel as for 18. PARIS, 20/06/1938.

20. RETOUR (M.Warlop) (Swing 100/mx.0SW 208) 2’35

21. NANDETTE (M.Warlop) (Swing 100/mx.0SW 209) 2’54

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON ORCHESTRE : Michel WARLOP (vln solo, arr, ldr)?; Paulette IZOIRD, Sylvio SCHMIDT, Émile CHAVANNES (vln)?; Charles LOUIS (Charlie LEWIS) (p)?; Tony ROVIRA (b)?; Armand MOLINETTI (dm). PARIS, 9/04/1941.

22. KERMESSE (M.Warlop) (Swing 124/mx.0SW 217-1) 2’35

23. AISÉMENT (M.Warlop) (Swing 125/mx.0SW 218-1) 2’56

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON SEPTUOR Á CORDES : Section de cordes comme pour 20-21 / String section as for 20-21?; plus Jean “Matelo” FERRET, Gaston DURAND (g)?; Francis LUCA (b). PARIS, 18/06/1941.

DISCOGRAPHIE / DISCOGRAPHY

CD 2 (1941-1943)

1. TEMPÊTE SUR LES CORDES (M.Warlop) (Swing 125/mx.0SW 219-1) 2’32

2. HARMONIQUES (M.Warlop) (Swing 124/mx.0SW 216-1) 3’02

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON SEPTUOR Á CORDES : Michel WARLOP (vln solo, arr, ldr)?; Paulette IZOIRD, Sylvio SCHMIDT, Émile CHAVANNES (vln)?; Jean “Matelo” FERRET, Gaston DURAND (g)?; Francis LUCA (b). PARIS, 18/06/1941.

3. STRICTEMENT POUR LES PERSANS (Strictly for the Persians) (L.Clinton) (Columbia DF-2819/mx.CL 7460-1) 2’40

4. SAUT D’UNE HEURE (One O’Clock Jump) (W.Basie) (Columbia DF-2819/mx.CL 7461-1) 3’23

LE JAZZ DIXIT – Dir. Raymond LEGRAND : Al PIGUILHEM, Alex RENARD (tp)?; Guy PAQUINET (tb)?; ? Hubert ROSTAING (cl)?; Roger FISBACH (as)?; Noël CHIBOUST (ts)?; Michel WARLOP (vln)?; Willy KETT (vib)?; prob. Daniel ROLAND (p)?; Louis GASTÉ (g)?; Francis LUCA (b)?; Harry KETT (dm). PARIS, 3/07/1941.

5. FUMÉES (G.Paquinet) (Swing 121/mx.0SW 232-1) 2’44

6. IDA (E.Leonard) (Swing 121/mx.0SW 233-1) 2’56

GUY PAQUINET ET SON ORCHESTRE : Pierre ALLIER, Jean LEMAY, Albert PIGUILHEM (tp)?; Guy PAQUINET (tb, arr, ldr)?; Charles LISÉE, Roger BERDIN (as)?; Jean LUINO, Roby DAVIS (ts)?; Michel WARLOP (vln)?; Henri GAUTIER (p)?; Tony ROVIRA (b)?; Jean PRINCÉ (dm)?; Willy KETT (vib). PARIS, 16/09/1941.

7. SWING CONCERTO (I & II) (M.Warlop) (Swing tests/mx.2SW 255-1 & 256-1) 7’39

MICHEL WARLOP ET L’ORCHESTRE SYMPHONIQUE DE JAZZ DE PARIS. Dir. ROBERT BERGMANN

Michel WARLOP (vln solo, orch) & 3tp, 3tb (incl. Guy PAQUINET), 2cl, 4 saxes, 2fl, 2ob, 2 bassons, 4 cors/horns, 16vln, 8vla, 6 vcl/cellos, prob. Pierre SPIERS (harp), 1g, 6b (incl. F. LUCA, Lucien SIMOËNS, Marius COSTE), 3dms (incl. Pierre FOUAD), timbales/tympany. PARIS, 17/02/1942.

8. NITE (M.Warlop) (Swing 139/mx.0SW 257-1) 2’41

9. SUR QUATRE CORDES (M.Warlop) (Swing 139/mx.0SW 258-1) 2’23

10. POKER (M.Warlop) (Swing 152/mx.0SW 259-1) 2’41

11. MI LA RÉ SOL (M.Warlop) (Swing 152/mx.0SW 260-1) 2’38

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON SEPTUOR Á CORDES : Michel WARLOP (vln solo, arr, ldr)?; Paulette IZOIRD (vln sur/on 8 & 9)?; Sylvio SCHMIDT, Émile CHAVANNES (vln)?; Pierre SPIERS (harpe)?; Louis GASTÉ, Émile FELDMAN (g)?; Francis LUCA (b). PARIS, 18/03/1942.

12. KIBOULA (J. Lutèce) (Fumière JF 501/mx. Part 1844-1) 2’52

13. MODERNISTIC (M. Warlop) (Fumière JF 501/mx. Part 1845-1) 3’14

MICHEL WARLOP ET SES QUINZE SOLISTES DE JAZZ : Al PIGUILHEM, Raymond SABARITCH, Alex RENARD (tp)?; Christian FINOL (tp, tb)?; Pierre DECK, Guy PAQUINET (tb)?; Raoul COURDESSE (cl, ts)?; Jean MAGNIEN (fl, as)?; Désiré DURIEZ (as)?; Noël CHIBOUST (ts)?; Michel WARLOP (vln, arr, ldr)?; Raoul GOLA (p)?; Louis GASTÉ (g)?; Francis LUCA (b)?; Armand MOLINETTI (dm). PARIS, 25/11/1942.

14. C’EST DU RYTHME (De Driessen-M.Erlangé) (Fumière JF 502/mx. Part 1846-1) 2’25

LES CHANTERELLES, acc. par Michel WARLOP et son Orchestre : “Les Chanterelles”(quintette vocal féminin/feminine voc quintet) acc. par la formation présente sur 12 & 13 / by the personnel present on 12 & 13. Paulette IZOIRD, Sylvio SCHMIDT, Raymond GOUTARD (vln) remplacent/replace DECK, GOLA & CHIBOUST. PARIS, 25/11/1942.

SI TU ME DIS OUI (A.Combelle-L.Gasté) (Rythme C 2137/mx. Part 1860-1) 3’00

PIERRE MINGAND, acc. par MICHEL WARLOP et son orchestre : Formation comme pour 14 / Personnel as for 14. Plus Camille SAUVAGE (cl, as). PARIS, 4/01/1943.

16. OUI (A.Combelle-L. Gasté) (Swing 167/mx.0SW 368-1) 2’47

17. CHRISTIANA (M.Warlop) (Swing 177/mx.0SW 365-1) 2’45

18. CHROMATIQUES (M.Warlop) (Swing 177/mx.0SW 366-1) 2’29

19. MICKEY (M.Warlop) (Swing 167/mx.OSW 367-1) 2’58

MICHEL WARLOP ET SON SEPTUOR Á CORDES : Michel WARLOP (vln, arr, ldr)?; Sylvio SCHMIDT, Émile CHAVANNES, Raymond GOUTARD (vln)?; Pierre SPIERS (harpe)?; Louis GASTÉ, Émile FELDMAN (g)?; Francis LUCA (b). PARIS, 13/07/1943.

20. MICHOU (M.Warlop) (ABC-Jazz Club 0673/mx.ST 960) 2’55

21. LOUBI (M.Warlop) (ABC-Jazz Club 0673/mx.ST 961) 3’21

22. PRISE DE COURANT (M.Warlop) (ABC-Jazz Club 0674/mx.ST 962) 2’20

23. ELYANE (M.Warlop) (ABC-Jazz Club 0674/mx.ST 963) 3’02

MICHEL WARLOP et son Ensemble : Christian WAGNER, Camille SAUVAGE, Paul JEANJEAN (cl & saxes)?; Michel WARLOP (vln solo, arr, ldr)?; Paulette IZOIRD, Sylvio SCHMIDT, Raymond GOUTARD (vln)?; Lucien GALLOPAIN, Roger CHAPUT (g)?; Pierre SPIERS (harpe)?; Emmanuel SOUDIEUX (b). PARIS, ca. Nov. 1943.

MICHEL WARLOP

Voici beau temps qu’Alain Gerber voulut mettre en évidence le caractère paradoxal du violon dans le jazz en opposant un «?jazz violonistique?», rattaché aux valeurs de la vieille Europe et de la musique dite «classique», à un «violon-jazz» s’étant parfaitement adapté, comme les autres instruments, au langage et à la syntaxe de la musique afro-américaine. Dans la première catégorie prendraient place des gens comme Joe Venuti, Eddie South, Stéphane Grappelli, Helmut Zacharias en ses jeunes années, voire même, quelque peu ambigu, Svend Asmussen, tandis que la seconde accueillerait Juice Wilson, Ray Nance, Stuff Smith ou Jean-Luc Ponty et Didier Lockwood… Quant à Michel Warlop, à qui Pierre Guingamp vient enfin de consacrer un gros bouquin sérieux et documenté (préface de Ponty), le premier dans son genre (Michel Warlop – Génie du violon swing – L’Harmatan, 2011), on n’a jamais très bien su où le coller. Entre les deux peut-être ? Moralité, on en fit un inclassable et on le voua à l’abandon. Chose d’autant plus facile qu’il est mort jeune. Ne point trouver place dans les petits tiroirs mentaux si pratiques est un péché rédhibitoire. Un inclassable est un maudit…

A ce qu’on dit, au commencement était la trompette (ou, plus exactement, le cornet). Du côté de La Nouvelle Orléans, on vous raconterait volontiers qu’au commencement, il y avait surtout, mais oui, le violon qui menait les autres à la baguette, et que la trompette (ou le cornet) eut bien du mal à remettre à sa place l’instrument du Diable. Mais enfin, elle y parvint et longtemps, les trompettistes tirent là-bas le haut du pavé : Buddy Bolden, Bunk Johnson, Emmanuel Perez, Freddy Keppard, Joe Oliver, “Papa” Jack Laine et quelques autres… Et puis, au bout de la chaîne (et au commencement d’une autre), il y eut, c’était fatal, le Roi des Rois : Louis Armstrong en personne. Lui, c’est vraiment dans la décennie la plus créatrice de ce siècle de fer, les années 1920, qu’il a explosé. Or en ce temps-là, il y avait justement un pianiste des plus novateurs, Earl Hines, tenu pour l’inventeur d’un “trumpet-piano style”, parce qu’il reproduisait sur son clavier les inflexions d’une trompette. Bien entendu, il joua avec Louis Armstrong et forma même avec lui, vers 1927-28, l’un des plus beaux duos qu’ait connu l’histoire du Jazz… La preuve absolue, irréfutable, ne manque pas de sauter aux oreilles à l’écoute des volumes 4 et 5 de l’intégrale consacrée à Satchmo par Frémeaux & C° (FA 1354 & 1355).

Au même moment, sur l’autre rive de l’Atlantique, un jeune homme plutôt balaise en musique qui s’amusait à rafler tous les prix d’excellence aux Conservatoires de Lille et de Paris, se mit à écouter avidement les premiers disques disponibles en France d’Armstrong et Hines – et aussi ceux de quelques autres, Bix Beiderbecke, Frankie Trumbauer, Eddie Lang, Joe Venuti… En un mot, du “jazz”. Il avait pourtant déjà une gentille petite carrière de concertiste classique derrière lui, ce garçon doué : concert organisé dans sa ville natale début 1927 avec, au programme, Fauré, Debussy, Borodine, Lalo ; autre concert, à Pleyel cette fois, l’année d’après pour ce Premier prix de violon du Conservatoire national de Paris, qui vient d’être nommé Premier violon solo et chef en second de l’orchestre des concerts Robert Siohan, ainsi que Premier violon chez Walter Straram… Mais le jazz… Voilà comment, à un beau destin tout tracé, la fougue de la jeunesse s’engouffra body and soul dans l’aventure ! Victor Gallois, Directeur et Prix de Rome, son Maître (qui fut aussi celui de Dutilleux), et Piero Copolla, compositeur, chef d’orchestre réputé, patron depuis le début des années 1920 de la Compagnie française du Gramophone, qui voyaient en lui l’un des quatre ou cinq violonistes du siècle, ne lui pardonnèrent jamais tout à fait. Mais Copolla l’aida souvent lors de la tentative de grand orchestre, dans la première moitié des années 1930, lui procurant nombre de séances d’enregistrement, notamment en qualité d’accompagnateur de chanteuses (Germaine Sablon, Eliane de Creus, Cora Madou…) et de chanteurs (Maurice Chevalier, Aimé Simon-Girard, Jean Sorbier, Ole Cooper, Robert Burnier, Petit Mirsha…).

Le violon n’est certes pas l’instrument que l’on croise le plus fréquemment dans le jazz : «c’est un truc de filles», affirmaient sans rougir quelques crétins bien trempés ! Michel Warlop – car c’était lui ! – ne fut tout de même pas le premier dans sa partie à jouer la carte de la nouvelle musique. Dès les années 1920 aux USA, Joe Venuti et Matty Malneck (de chez Paul Whiteman) du côté blanc, Eddie South, «Juice» Wilson, Darnell Howard du côté noir, avaient déjà sérieusement débroussaillé le terrain. En France même, Stéphane Grappelli, de trois ans l’aîné de Michel, était sur la brèche : d’abord inspiré par Venuti, il se tourna ensuite vers South, joua et enregistra au cours d’un longue carrière avec l’un et l’autre et finit par se forger son style bien à lui, modèle d’équilibre, de swing et d’élégance. Ces musiciens, en tous cas, pratiquèrent pour la plupart le violon comme tout violoniste bien élevé est censé le faire, même si Venuti s’amuse sans vergogne à placer l’instrument entre le crin et la baguette de l’archet, ou si Wilson se plait à arracher quelque peu avec l’aide de l’électricité (voir le recueil intitulé Violon Jazz – Frémeaux FA 052). Sauf Michel Warlop. Non qu’il ne fût pas bien élevé, non qu’il n’eût point écouté les autres (avec, du reste, un vague sentiment de frustration, notamment à l’endroit du raffinement de son ami Stéphane), mais son tempérament inquiet, sa nervosité et aussi, sans doute, sa conception du jazz, l’incitèrent à faire sonner l’instrument autrement – un peu comme Hines faisait sonner le piano. En somme, Michel Warlop inventa un “trumpet-violin style”, avec juste ce qu’il fallait de lyrisme écorché vif…

C’est à Douai, ville minière, industrielle, du nord de la France, titulaire du deuxième plus ancien conservatoire de musique du pays (1806), que Michel Warlop vit le jour le 23 janvier 1911 et c’est à l’autre bout de l’hexagone, à Bagnères de Luchon, qu’il s’en alla baguenauder sur les verts pâturages trente-six ans plus tard, le 6 mars 1947. Michel Warlop n’a guère voyagé, à l’exception de petites escapades outre-Quiévrain (donc pas bien loin de chez lui) et d’un séjour pas vraiment joyeux outre-Rhin en 1940-41… On ne tarda d’ailleurs pas à renvoyer dans ses foyers ce prisonnier de trente ans en déjà pas très bon état, en se demandant comment il avait diantre pu être mobilisé ! Il en rapporta néanmoins la mise en musique symphonique du poème de Jean Mariat Le Noël du Prisonnier, enregistré le 17 février 1942 au studio Albert par Jean Davy en récitant et le compositeur à la direction d’orchestre. Ce 30 centimètres 78 tours Columbia DFX-240, ne trouva que sept cent septante-cinq (775) acquéreurs en près de cinq ans. Et deux cents trente-deux exemplaires furent cassés, sur les mille et sept pressés. Misère…

Les voyages ne forment pas obligatoirement la vieillesse, la sagesse pas davantage et, dans sa tête, pourvu qu’on l’ait bien pleine et surtout pas trop bien faite, il arrive que l’on découvre des paysages autrement plus beaux – ceux que l’on a inventés… Etonnante bête à concours fermement dirigé par sa pianiste (amateur) de maman, le petit Michel décrocha donc plusieurs médailles à Lille et, tout naturellement, quitta la pâtisserie familiale de la Grand Place de Douai dirigée par son papa (une force de la nature qui, dit-on, n’aimait pas trop qu’il s’entraînât pendant le jour pour ne pas indisposer la clientèle, qui buvait sec, ne dormait que quelques heures par nuit et qui lui survivra longtemps), afin de poursuivre dans la carrière des honneurs en première ligne. A savoir à Paris où, fatalement, il croisa le mal (ou le Malin) – cette “musique décadente judéo-nègre” (comme on ne disait pas encore !) connue sous le nom de “jazz”…

Il existait vers la fin des années 1920 des tas de boîtes, tant à Montmartre et à Montparnasse qu’aux Champs-Elysées, spécialisées dans ce genre d’exotisme. Michel y croisa des Américains de passage et aussi les premiers représentants du jazz hexagonal : Philippe Brun, Pierre Allier, Alex Renard, André Ekyan, Alix Combelle, Alain Romans, Stéphane Mougin, Lucien Moraweck, Léo Vauchant, Roger Fisbach, Guy Paquinet… Mais pas Django, lequel, à l’époque, travaillait surtout dans le milieu musical assez différent du musette. En revanche, Grappelli faisait bien partie de la famille, encore qu’il ne refusât point à l’occasion de jouer dans des orchestres de tango. C’est même dans l’un d’eux, lors d’une séance de disques, que le “Sublime Grégor” le repéra en 1929 et l’engagea – non comme pianiste, ainsi que le prétendait l’intéressé, mais bien comme violoniste. L’Arménien Krikor Kélékian, génial dilettante qui ne jouait lui-même d’aucun instrument mais qui savait admirablement se vendre, dirigeait alors ses “Grégorians”, probablement la meilleure grande formation de jazz français – en fait plutôt cosmopolite, puisque comprenant, outre Grégor lui-même, un saxophoniste suisse, un batteur écossais et plusieurs Russes blancs !

Michel et Stéphane (son aîné de trois ans), se trouvèrent suffisamment d’affinités pour très vite partager le même petit appartement montmartrois. Côté violon toutefois, si leur admiration pour Heifetz est réciproque, Grappelli aurait plutôt un faible pour Joe Venuti, alors que Warlop ne jure que par Eddie South, dont quelques jolies faces de 1927-28 ont été éditées en Europe. Vers le milieu des années 1970, Stéphane affirmait volontiers qu’ «?en ce temps-là?» (soit quarante ans plus tôt), il n’y avait que trois violonistes capables de jouer “hot” : Venuti, Michel Warlop et lui… Impossible de lui faire admettre qu’Eddie South était aussi un sérieux client : «?Eddie, je ne l’ai connu qu’à la fin des années 30, quand on a enregistré ensemble?». Pourtant, South jouait à Paris début 1929 et y enregistra même un disque. C’est certainement à cette occasion que Michel l’entendit et s’en enticha. Difficile de croire qu’il n’en parla pas à Stéphane. Encore plus difficile de croire que celui-ci, curieux de nature, ne se soit point déplacé, ne serait-ce qu’un soir, pour l’écouter…

Dans Un Opéra-Jazz, court “film-attraction” du début de l’an 1930 réalisé sur la scène de «L’Empire» où l’orchestre participait à une revue, on a la preuve que Grappelli est alors bien violoniste (et non pianiste). L’un des deux autres violons est certainement René Cézard, l’autre étant peut-être Sylvio Schmidt – en tous cas pas de Warlop là-dedans. Lequel ne fera son entrée dans le groupe qu’au printemps suivant, comme en témoignent quatre faces Columbia (Je chante sous la Pluie, Le Rugissement du Tigre…) du 29 avril 30, les premières, sans doute, qu’enregistra Michel… Du coup, Grappelli se trouva relégué au piano (instrument que, du reste, il affirmait avoir de tous temps préféré au violon). En conçut-il néanmoins quelque dépit ?

L’orchestre fit la saison d’été en Argentine, mais Michel, peut-être à cause de son jeune âge, ne fut pas du voyage. A Paris, il trouva de l’embauche au sein du Jazz Pathé-Natan, avec lequel il enregistra sans doute (sans toutefois prendre de solos). On l’entrevoit même, membre de ce groupe, admirant une danseuse acrobatique, au début du film (Pathé, bien entendu) Chacun sa Chance, réalisé à l’automne. Un titre prémonitoire pour certains : Warlop n’y est certes que figurant, mais il s’agit tout de même du premier film d’un certain Jean Gabin et d’un nommé Jean Sablon (qui, lui, ne fera pas carrière au cinéma) ; quant à ce tout jeune accessoiriste/habilleur plutôt gaffeur et sympa, il s’appelle Charles Trenet… Fin 1930, en compagnie des Grégoriens rentrés au pays, Michel grava quelques faces (rares) pour la petite et éphémère firme Aeolian. Mais, responsable d’un grave accident d’automobile, Grégor, blessé, jugea plus prudent de filer à l’anglaise… vers l’Argentine!

L’an 31 fut surtout consacré à un service militaire plutôt musical au 1er Régiment de ligne. L’année suivante, Michel Warlop dut jouer brièvement au Lido dans l’orchestre d’un mystérieux Harry Reser (rien à voir avec le fameux banjoïste virtuose américain) et participa à une séance de disques chez Ultraphone, avenue du Maine. Il retrouvera les studios de cette firme en 1933, puisque c’est elle qui signera en exclusivité la nouvelle formation de Grégor, retour d’exil fin 32, à la suite d’une amnistie. C’est là que débute vraiment le présent recueil, avec cette Fantaisie Grégorienne, composée et arrangée par Michel dans l’esprit du “jazz symphonique” et d’Ellington réunis, solo de violon par le compositeur à la clef.

La cuvée du printemps 33, produite par de belles étoiles du jazz local (Warlop, Grappelli, Pierre et Roger Allier, Ekyan, Fisbach, Alix Combelle, Moraweck, Mougin, Roger Grasset…) paraît aussi exceptionnelle que variée. La bande participe même au tournage d’une nouvelle version, “moderne”, de la célèbre pièce Miquette et sa Mère, avec Blanche Montel et Michel Simon (voir le recueil Ciné Stars – Frémeaux FA 063). Pourtant les disques se vendent mal en ces temps de crise, les engagements se font rares et les boîtes les plus réputées de la décennie précédente ferment. Les Grégoriens ont juste le temps de filer vers la Côte basque pour la saison d’été, mais celle-ci sera de courte durée. Avant même le retour à Paris, Grégor est contraint de licencier l’équipe. Une ultime tentative en 1934 avec d’autres musiciens qui n’enregistrent pas, ne sera pas davantage couronnée de succès. Et c’est ainsi que le Sublime Krikor Kélékian quittera définitivement la scène du jazz…

La fin de l’an 33 fut tout de même animée, qui vit l’enregistrement de nombreuses faces alimentaires par les ex-Grégoriens, le plus souvent regroupés sous la houlette de Michel et de Moraweck, pour les disques Etoile, les Editions de Paris, la maison SEDOEM pourvoyeuse de galettes dans les écoles de danse… Plus intéressantes sont les gravures parues sous le nom des “Chicago Syncopators”(sic), produites par le compositeur noir américain Henry Matéo (alias H. McKnight) sous son propre label. My Gal Sal et Harlem Hurricane contiennent de bonnes interventions du violoniste, dont l’identité se trouve mentionnée apparemment pour la première fois sur les étiquettes. C’est un groupe de studio sans doute assez proche qui grava pour une firme non identifiée, fin 33 ou début 34, un mystérieux Dr. Swing. En 1934-35 justement, outre ses débuts comme chef de grand orchestre à part entière et ses vrais premiers disques sous son nom en moyenne formation (All For the Swing, Crazy Fiddle), Michel répondit fréquemment à la demande d’autres formations lors de certains galas et séances d’enregistrement : le Jazz du Poste Parisien (direction Moraweck) et le Jazz Patrick (alias Guy Paquinet), comprenant plusieurs ex-Grégoriens, ainsi que, parfois, Django et Grappelli, eux-mêmes fondateurs d’un étonnant Quintette (à cordes) du Hot Club de France pas encore tout à fait régulier… Il ne manqua d’ailleurs pas, à son tour, de réquisitionner aussi souvent que possible ces deux-là pour ses disques (Presentation Stomp, Blue Interlude). En mars 1935, son orchestre accompagna Coleman Hawkins à Pleyel et dans les studios de la Compagnie du Gramophone. Lui-même ne jouait pas dans les disques…

A signaler que, toujours en 34-35, Warlop participa à une copieuse série d’enregistrements commanditée par les éditions musicales Echo, publiée sur leur propre marque et dirigée par le pianiste classique/compositeur Léon Kartun : des disques de danse à petit prix. Michel est surtout présent (avec deux autres violons) dans les premiers morceaux, dont Knick Knack Blues. Dans son gros ouvrage en langue anglaise consacré à Stéphane Grappelli (Sanctuary Publishing Ltd., London, 2003), Paul Balmer mentionne (p.79) un disque “classique” de 1934 dans lequel Kartun accompagnerait un violoniste du nom de Waclaw Niemczyk – lequel ne serait autre que Michel Warlop ! Malheureusement, il ne donne pas le titre de l’œuvre ni ne précise la marque de cette gravure… On sait à quel point Michel ne détestait pas la galéjade (ou plus exactement la zwanze, comme on dit par chez lui), lui dont l’orchestre anima les nuits folles du cabaret «?Chez O’Dett?», pour l’état civil René Goupil, célèbre travesti ayant peu auparavant donné leur chance aux débutants Charles (Trenet) et Johnny (Hess), très impliqué dans d’échevelées parodies (dont le génial Phèdre) concoctées par le Roi des Loufoques en personne, Pierre Dac. Sous le sobriquet de «?Vint’ d’Osier?», le mineur de fond Warlop participa même activement aux délires radiophoniques de Dac et sa bande. On est donc en droit de se demander si cette histoire de disque sous pseudo polonais ne relève pas tout bonnement du canular… Comme Danzig en somme.

Le grand orchestre grava encore quelques faces le 18 mars 1936, dont Little Girl Blue et Rhythm Step, mais l’influence de Piero Coppola diminuant singulièrement chez Gramo, il ne put se maintenir à flot grâce aux salvatrices séances. Déjà le 5 décembre 35, Michel avait enregistré quatre titres en petit comité, avec l’accordéoniste Louis Richardet et deux des frères Ferret, Matlo et Sarane. Ceux-ci seront remplacés par deux autres frères, Django et Joseph, dans les six pièces de la séance Polydor organisée par Marceau van Hoorebecke le 17 avril 1936 et comprenant également Alex Renard à la trompette, ainsi que les saxophonistes Maurice Cizeron et Alix Combelle. Les studios Polydor, dans le XIIIème arrondissement, le violoniste les connaissait déjà pour y avoir, sous la houlette de Wal Berg, accompagné Danielle Darrieux, Pierre Mingand, Henri Garat. Il y reviendra parfois rendre le même service à la Môme Piaf et, surtout, début juin 1937, pour participer à une bizarre session dont deux titres seulement semble-t-il, Désespérance et Doux Souvenirs, ne furent édités anonymement que début 1940… Lors de cette séance, les partenaires de Michel sont apparemment les membres de la petite formation dirigée par le pianiste d’origine italienne Pierre Zeppilli, avec laquelle le violoniste, en rupture de big band, travaillera souvent entre 1936 et 1939.

Ce groupe donna quelques faces chez Idéal sans grand intérêt pour le jazz, mais il lui arriva d’accompagner aussi (1938) Mireille, Jean Tranchant et André Claveau, ces deux derniers représentés dans ce recueil (CD 1, plages 18 et 19). Au fond, ce furent surtout les disques qui permirent à Warlop de gagner sa vie, même s’il joua régulièrement en boîte, le plus souvent pour des cachets indignes, lui qui avait toujours un pressant besoin d’argent, afin d’éponger le coût de l’alcool et de certaine substance nocive qu’il consommait de plus en plus. Il lui fallait aussi tenter de rendre la vie agréable à Nandette, épousée en 1935. Un mariage qui durera tant bien que mal une petite dizaine d’ans…

C’est avec la même équipe quelque peu augmentée (notamment du trompettiste André Pico et surtout d’un certain Django Reinhardt) que le 21 décembre de cette fort riche année 37, après la fin de l’Expo, Warlop grava trois titres pour la flambant neuve maison Swing, fondée par Charles Delaunay avec le concours d’Hugues Panassié et la complicité de Jean Bérard, directeur de Pathé-Marconi. Bien entendu, ces faces, ainsi que celles enregistrées le même jour et la semaine suivante par de petites unités à géométrie variable (duos, trios), se retrouvent toutes dans l’intégrale consacrée au fabuleux Manouche. Mais il n’était guère possible d’évoquer Michel Warlop sans inclure au moins deux ou trois pièces le donnant à entendre au côté du guitariste, son vrai frère à plus d’un titre. On trouvera donc ici, avec l’orchestre, l’envoûtant Taj-Mahal, sombre diamant aux sonorités orientales. Est également inclus, du 28 décembre, le très acéré Sweet Sue en quartette avec Django, Grappelli au piano, Louis Vola à la basse : Michel Warlop désormais dans toute sa maturité, en pleine possession de ses moyens…

En 1938-39, il joua encore beaucoup en boîte, surtout avec la bande à Zeppilli, participant notamment à la première Nuit du Jazz, au «Moulin de la Galette» le 30 juin 38. Si les accompagnements de chanteurs (Mireille, Claveau, Piaf, Léo Marjane) se succèdent heureusement toujours à bonne cadence, les disques sous son nom se font plus que rares : une seule face publiée (sur deux enregistrées) en 1938, un duo avec le pianiste Garland Wilson qui doit être réédité prochainement dans un recueil dévolu aux débuts de la maison Swing… Rien en 39. Mais il est vrai que cette année-là fut courte, du moins pour la musique, puisqu’en septembre le violoniste se trouva bel et bien mobilisé !

Non seulement mobilisé, mais fait prisonnier lors de la défense de Lille, au printemps de 1940. Au moins n’eut-il pas le triste sort d’un Maurice Jaubert, superbe compositeur massacré en ce temps des assassins. Résultat : sept mois de stalag, puis une libération début 41, peut-être à cause de son hémoptysie… Après l’armistice, la vie parisienne avait repris, à peine différente – pour les happy few du régime, bien entendu ! Les autres commençaient à crever de faim et de froid, en une période qui connut l’apogée du marché noir et les hivers les plus rigoureux du siècle…

Raymond Legrand, saxophoniste chez Roland Dorsay puis chez Ray Ventura, lui-même chef d’un éphémère orchestre (1933), arrangeur pour Ventura et gérant de la maison d’édition de ce dernier, avait le vent en poupe depuis que les patrons des anciennes grandes formations de music-hall s’étaient exilés ou, du moins, s’étaient faits fort discrets. Titulaire lui-même d’une belle grosse machine dès la seconde moitié de 1940, il gravait des tas de disques et passait sans arrêt sur les antennes de Radio Paris – ce qui lui vaudra quelques menus ennuis à la Libération… Il embaucha sur le champ Warlop à son retour de captivité, comme violoniste vedette, mais aussi comme compositeur et arrangeur. L’ouvrage ne manquait pas, entre les concerts en séries, la radio, les séances de disques (orchestre seul aussi bien que quantité d’accompagnements divers et variés) et même le cinéma en 42, avec Mademoiselle Swing, réalisation gentiment conventionnelle de Richard Pottier distribuant la vedette à l’équipe et à sa chanteuse/danseuse Irène de Trébert (voir le recueil à elle consacré : Frémeaux FA-056)… Aussi bizarre que cela puisse sembler, on est en droit d’affirmer que ce fut là l’une des périodes les plus fastes, les plus prolifiques, du spectacle français. Pour ce qui touche le jazz (et assimilé), l’une des raisons est probablement le manque de concurrence, due à l’absence des Américains et de la plupart de leurs disques récents. Ainsi donc, Django Reinhardt devint du jour au lendemain une grande vedette populaire. Et Michel Warlop connut lui aussi un succès certain.

Outre la grande formation de vingt à trente exécutants, Legrand produisit aussi un groupe “swing” plus réduit, le Jazz Dixit (le jeu de mot de rigueur ne dut point déplaire à Michel), qui joua souvent en public et à la radio en 1941, mais n’enregistra que quatre faces, deux compositions originales gauloises et deux traductions de l’américain, Strictement pour les Persans (Strictly for the Persians) et Saut d’une Heure, titre sous lequel on reconnaîtra habilement dissimulé un certain One O’Clock Jump attribué à un Comte. Cette mode des titres francisés donna lieu à de cocasses trouvailles, comme Parade des Remparts du Sud, Danse nègre après la Moisson, Parc Royal, Vous avec un beau Chapeau, Madame ou encore L’orgue moud du Swing. Le Hot Club de France organisa même des concours. En revanche, La Tristesse de Saint Louis (St. Louis Blues) et Les Bigoudis (Lady Be Good) n’ont été relevés sur aucun document d’époque. Dommage…

Comme si tout cela ne suffisait pas, Michel participa à quelques séances patronnées par des collègues de l’orchestre comme Guy Paquinet (jadis “Patrick”), réquisitionné par Swing pour Fumées et Ida (pas besoin de le traduire, celui-là). Fin 1942, Legrand lui prêta encore la quasi totalité de ses musiciens pour la gravure, commandée par la firme franco-belge Fumière, de deux accompagnements du quintette vocal féminin des Chanterelles et de deux instrumentaux à sortir sous son nom, Kiboula et Modernistic, sa composition au titre ironique. Les mêmes, ou presque, accompagnèrent Pierre Mingand dans Oui, gentil “tube” du moment qu’ils connaissaient bien, le 4 janvier 43…

Oui, cette chanson d’Alix Combelle et Louis Gasté, dont le refrain est entièrement constitué de titres d’autres arias plus ou moins récentes (Parlez-Moi d’Amour, Seule ce soir, J’attendrai, Tu m’apprendras, Quand viendra le jour, Le Premier Rendez-Vous, Fleur bleue…), Michel Warlop en offrit également une version instrumentale à la tête de son Septuor à cordes. Là encore, de 1941 à 1944, le grand orchestre de Legrand fut un réservoir idéal, lui fournissant sa section de cordes (Paulette Izoird, Sylvio Schmidt, Emile Chavannes, Raymond Goutard), quelques uns des guitaristes (Gasté, Emile Feldman), l’homme à la harpe (Pierre Spiers)… Parfois des éléments extérieurs, comme Matelo Ferret, se glisseront dans la place. En fait, lors de la toute première séance chez Swing, le 9 avril 41, la formule – la plus originale, sans doute, mise en œuvre dans le jazz français depuis la fondation du légendaire quintette à cordes du HCF – n’est pas tout à fait au point, puisqu’il y a là un piano (instrument à cordes, cependant) et un batteur. Ce qui n’empêchera pas les deux morceaux du jour, Retour et surtout Nandette, d’être de parfaites réussites et d’annoncer la suite sans détour.

La suite, c’est une douzaine de cires gravées en trois séances tenues au studio de la rue Albert, les 18 juin 1941, 18 mars 42 et 13 juillet 43. Oui provient de cette ultime session, alors que le délicat Harmoniques et l’aérien Tempête sur les Cordes, deux des exécutions les plus remarquables, sont issus de la première. A cette exceptionnelle série, intégralement reproduite dans ce recueil, peuvent encore se rattacher Michou, Loubi, Prise de Courant et Elyane, quatre faces enregistrés fin 1943 pour la marque concurrente de Swing, ABC-Jazz Club – les derniers disques à sortir (fugitivement comme des voleurs, ou presque) sous le nom de Michel Warlop. Ici cependant, comme pour la séance Nandette d’avril 41, le “tout cordes” n’est pas de rigueur, puisqu’on relève la présence d’un clarinettiste et de deux saxophonistes – encore des gens de chez Legrand. Toutefois, l’atmosphère reste sensiblement la même.

Après consultation des hebdomadaires de radio (notamment Les Ondes, émanation pur jus de Radio Paris), on sait que le Septuor fut assez souvent diffusé sur l’antenne de la station menteuse (mais la Radio Nationale, Radio Vichy & C°, n’étaient guère en reste pour le baratin !). On sait aussi, au vu de titres différents de ceux des disques, qu’il s’agissait bien d’enregistrements spécialement réalisés pour une diffusion à la TSF. Sur bande (il y avait déjà quelques magnétophones à Radio Paris) ? Sur laques ? Que sont-ils devenus ? La mise à sac des archives de la station en août 44 laisse supposer le pire. De toutes façons, même si toutes ces choses avaient survécu, leur état de décomposition avancé ne permettrait sûrement pas de les réentendre. Signalons que le Septuor, outre les disques et les ondes, se produisit de temps en temps en public, en particulier à Pleyel.

Et puis, il y a évidemment ce Swing Concerto, commencé aux jours de la captivité, terminé après le retour à Paris, sur l’insistance de Raymond Legrand. Pas moins de soixante-quatre exécutants, réunis sous la baguette de Robert Bergmann au sein du Jazz Symphonique de Paris, furent mis à contribution les 6 et 7 décembre 1941 dans une salle Pleyel comble, interprétant aussi bien Ravel et Debussy que le Boléro de Django Reinhardt. Et aussi, bien entendu, l’insolite Swing Concerto pour Violon et Orchestre de Michel Warlop, avec en soliste le compositeur. Le deuxième jour, dimanche 7 décembre, eut lieu l’attaque japonaise sur Pearl Harbour, mais on aurait tort de chercher un lien de cause à effet entre cet évènement capital dans la poursuite de la guerre et la création parisienne d’une œuvre symphonique injustement oubliée.

L’œuvre en question, bien que jugée “ hybride ” par les puristes de tous bords, fit quand même l’objet d’un enregistrement sur deux faces du 78 tours de trente centimètres, en date du 17 février 1942 – le même jour que Le Noël du Prisonnier, sorti sous étiquette Columbia. Le Concerto, lui, aurait dû paraître chez Swing. Mais il y avait une telle pénurie de gomme-laque en ce temps-là, ma pauv’ dame !... A tout le moins, les tests furent-ils diffusés à plusieurs reprises sur les antennes des radios. Les auditeurs purent tout de même entendre le “chef-d’œuvre” (au sens que le Compagnonnage attache à ce terme) de Michel Warlop. Un an après, le 23 février 1943, une seconde version où le violoniste Pierre Darrieux remplaçait le compositeur fut enregistrée pour Columbia (RFX 77) avec le même orchestre. Il s’en vendit en cinq ans quelque huit cent six exemplaires…

En 44, Raymond Legrand se mit à recevoir des petits cercueils et préféra quitter Paris en mai avec sa compagne Irène de Trébert. L’orchestre se désintégra et Warlop sauta sur un engagement à Lille dans une boîte connue, avec passage hebdomadaire à la radio locale. Il n’existe malheureusement aucun document enregistré de cet épisode, mais on sait que la jeune chanteuse du groupe s’appelait encore Jacqueline Ray et qu’elle se ferait connaître quelque temps plus tard sous le nom de Line Renaud. Bref passage par Paris après la Libération, puis tournée dans le Sud-Ouest, avec concerts à Toulouse en compagnie de Charles Trenet. C’est du reste au côté de ce dernier que Michel participa le 25 juillet 1945, accompagnateur anonyme très reconnaissable (notamment sur Chacun son Rêve) au sein d’une formation dirigée par Henri Leca, à ce qui doit bien être son ultime séance de phonographe.

Après un éphémère nouveau Septuor, une condamnation à trois jours d’indignité nationale et à deux mois d’interdiction professionnelle à Paris, Michel Warlop préféra jeter l’éponge et rejoindre son ami Zeppilli à Bordeaux, sans espoir de rejouer. Encouragé par le pianiste et par ce jeune admirateur du nom de Frank Ténot, il ne tint pas parole et trouva de l’embauche sur place, puis à Perpignan, pour finalement se retrouver au luxueux «?Grand Hôtel?» de Font-Romeu, afin d’y assurer l’animation des fêtes de fin d’année. Il s’y produisit longuement en compagnie du trio du jeune pianiste Jimmy Réna, comprenant son épouse Mano, le batteur Georges Herment et la chanteuse Anita Love. Avec les mêmes, il joua aussi à Carcassonne et à Biarritz, avant d’émigrer fin 46 vers le « Grand Hôtel » de Super-Bagnères. Là s’arrêta son périple, lui qui voyageait si peu, à la date du 6 mars 1947. Lors de la dernière soirée costumée, il s’était effondré, fiévreux, grippé sans doute. Puis on le transporta à l’hôpital de Bagnères-de-Luchon et on se mit à parler de phtisie, mais l’alcool y était évidemment pour beaucoup. Michel Warlop est certes mort d’épuisement, mais aussi, surtout, du mal de vivre, du goût du risque, de la passion de la Liberté…

Nouveau venu dans la troupe, le jeune saxophoniste/clarinettiste Guy Lafitte, dont c’était l’un des tout premiers engagements professionnels, laisse dans son livre de souvenirs un émouvant témoignage : «Il y avait un étrange personnage, pâle, aux yeux délavés, vêtu d’une chemise de l’armée américaine, d’un pantalon de même provenance, il n’avait pas l’air de grand-chose. A mes yeux un vieil homme fragile presque au bout du rouleau qui n’avait rien d’impressionnant jusqu’à ce que je l’entende. Cet être diaphane qui semblait venu d’un autre monde et prêt à y retourner était Michel Warlop, un véritable cas dans notre musique. Il ne devait avoir guère plus de trente-cinq ans alors mais qui aurait pu le croire ? Quand il a joué, je n’ai pas compris grand-chose mais j’ai senti une certaine grandeur dans sa musique, quelque chose, qui me dépassait mais forçait mon respect. Je n’ai pas véritablement aimé mais j’étais médusé. (…) Il est le premier que j’ai vu véritablement souffrir de son art, de son corps, de son besoin de dire l’inexprimable. (…) A n’en pas douter, Grappelli était fait pour jouer avec Django… Warlop était fait pour souffrir seul.» (Guy Lafitte, Comme si c’était le Printemps, ArtMédia Editions, 2003).

MICHEL WARLOP — Á propos de la présente sélection

Redisons-le : pas question de reprendre ici l’entièreté des faces mettant en présence Django Reinhardt et Michel Warlop. Elles ne sont d’ailleurs pas si nombreuses, au fond : une petite vingtaine, si l’on exclut les accompagnements de vocalistes et quelques fragments de radios ou d’enregistrements d’amateurs de qualité technique douteuse. Pour mémoire, on rappellera que la plus ancienne, Presentation Stomp, remonte au 16 mars 1934 et que la dernière, Mélodie au Crépuscule (sous le nom du guitariste et avec d’autres violonistes), date du 7 juillet 43. Deux exceptions toutefois, avec Taj Mahal et Sweet Sue de décembre 1937, merveilleux chefs-d’œuvre reinhardto/warlopiens et preuve absolue de la parenté souterraine, invincible, totale, liant à jamais les deux musiciens. Le reste – dont les tout aussi prodigieux Serenade for a Wealthy Widow et Christmas Swing – est à (re)découvrir dans l’intégrale ou le second volume de «La Quintessence» (FA-205) dévolu au génial Manouche…

Á vrai dire, même dans les gravures des années 1933-36 sans Django publiées sous son nom, Warlop est loin de se faire toujours entendre en soliste, trop occupé sans doute à diriger l’orchestre et à faire exécuter ses arrangements. Ainsi, lors de la séance du 18 mars 36, il ne retrouve son violon que sur les deux titres ici reproduits, Little Girl Blue et Rhythm Step, les trois autres morceaux (Alone, First You Have Me High et The Lady Dances) ne comportant nulle intervention de sa part. Dans les gravures des «?Chicago Syncopators?», son identité, comme auteur d’un “solo de violon hot”, n’est dévoilée que pour les deux reprises ici, My Gal Sal et Harlem Hurricane, les trois autres (Hunkadola, Small Town Girl, All the Time), désespérément fades, ne le mentionnant pas, puisqu’il n’y prend aucun solo. La réédition, cette fois sous le nom de Michel, de quatre de ces faces par Columbia en 1936 dut passablement décevoir les amateurs, réduits à la portion congrue d’un seul et unique morceau ! Quant au mystérieux test Dr. Swing, probablement de la même époque, il est à peu près certain qu’il ne fut jamais publié commercialement.

Michel n’est guère davantage audible dans la plupart des pièces de 1933-36 où son orchestre accompagne les chanteurs (Chevalier, Germaine Sablon…) : là encore, arrangeur et directeur, il n’avait point le loisir de se livrer à ses si chères fulgurances. Toutefois, lorsqu’il cessait d’être le chef, comme dans les disques de Danielle Darrieux ou Edith Piaf (direction Wal Berg ou Jacques Météhen) ou ceux pour lesquels Zeppilli prenait la relève (avec Claveau et Mireille, par exemple), il lui était permis de glisser sa signature en douce… A propos de chanson, on notera que sur Miss Otis regrette, c’est lui qui chante. Il récidivera le 5 décembre 35, lors de la séance avec Richardet et les Ferret, dans Mirage (Chasing Shadows – 0LA 750), mais ce coup-ci, ça ne passera pas ! On n’a pas retrouvé de matrice…

C’est pourtant bien avec ces enregistrements-là – du moins les trois édités : les véloces Strange Harmony et Double Trouble, le doux Sérénade – que Michel Warlop violoniste devient vraiment Michel Warlop. Les deux faces de janvier 34, All for the Swing (variation sur Tiger Rag) et Crazy Fiddle, ont cependant déjà donné une bonne idée de sa valeur, mais une certaine raideur subsiste (d’ailleurs due en partie aux partenaires), également perceptible dans les gravures ultérieures en grande formation. En somme, tout comme Django Reinhardt, le violoniste, compositeur, arrangeur, rêvait de grands orchestres mais se trouvait plus à l’aise en petits comités. On en à la preuve éclatante avec les six pièces aux titres bizarres (Cloud Castles, Novel Pets, Budding Dancers…), chez Polydor en avril 36 avec Django (voir Intégrale D.R. vol. 4 – FA 304) et, plus encore, dans la plupart des faces Swing de la fin 1937, toujours en compagnie du flamboyant Manouche – le sombre Taj Mahal, le délicieux et swinguant Serenade for a Wealthy Widow, le diabolique Christmas Swing, l’âpre Sweet Sue en première ligne…

Désespérance et Doux Souvenir, mélancoliques à souhait, gorgés de ce spleen dont Warlop raffolait tant, sont des rescapés que Polydor, en panne de nouveautés, ne se décida à sortir qu’au temps de la “drôle de guerre”, presque trois ans après leur enregistrement ! Deux faces annonçant celles de Swing ci-dessus mentionnées, mais cette fois sans Django, probablement retenu par une partie de billard ; du coup, c’est son petit frère qui s’y est collé. Il est à peu près certain que le premier titre est le résultat d’un montage de deux prises différentes (changement de couleur à l’entrée du solo de guitare). La feuille de studio a disparu et les quatre matrices précédentes et les deux suivantes sont inconnues. Ont-elles été éditées sur quelques galettes perdues dans la tourmente de l’époque ? Quels titres leur avait-on donné ? Tristesse ? Cœur gros ? Pleurs ? Deuil en vingt-quatre Heures ? A moins, suivant le principe de la douche écossaise, qu’on ne se soit soudain tourné vers le bonheur…

La création du Septuor à cordes demeure certainement l’initiative la plus heureuse de Michel Warlop, son coup de génie, n’en déplaise à ceux qui jugèrent cela “emmerdant”. L’usage des cordes dans le jazz n’était certes pas nouveau, on le sait. Les prédécesseurs avaient noms Joe Venuti et Eddie Lang, Eddie South et, bien entendu, Stéphane Grappelli et Django Reinhardt flanqués du légendaire quintette. En ce début des années 1940, le public était donc déjà familier de la formule. Le jazz, le swing, pouvaient ne pas être uniquement l’apanage des cuivres et des anches. Pierre Guingamp : « Avec son Septuor, Michel apporte au jazz nouveauté et originalité. (…) Le Quintette du Hot Club avait déjà donné aux cordes leur noblesse. Mais la voie explorée ici est différente, poussant plus avant dans l’invention, mêlant la forme réfléchie à l’imprévisible, dans la prééminence du violon.?» (op. cité). Ce fut là, en tous cas – malgré la dureté des temps –, la période la plus sereine de la carrière de Michel Warlop, éternel angoissé, qui découvre-là un plaisir à jouer enfin, tout naturellement, une musique selon son cœur, puisée comme une claire eau de roche tout au fond de son être. Le droit de mêler les genres, les sonorités, de faire alterner sans rupture le savant et le populaire, de passer des dissonances de la virtuosité swing aux harmoniques les plus subtiles. Signalons que certains titres du Septuor font la part belle à l’entourage de Michel : ainsi Nandette est-il le diminutif de son épouse, alors que Nite est le surnom d’une charmante cousine et que Mickey n’est point la malicieuse souris bien connue des dessins animés, mais… sa belle-mère !

Au fond, cette “atmosphère Septuor” va bien au-delà des seuls disques de cette formation. On la retrouve aussi bien dans les quatre faces finales (dont le très délicat Elyane) que sur les deux morceaux avec Paquinet, ou dans Modernistic en 42 et en grande formation (infiniment plus souple que quelques années plus tôt). Titre ironique choisi par le compositeur, d’abord en référence à Debussy qu’il admirait et dont certaines œuvres, au début du siècle, avaient ainsi été qualifiées non sans mépris par les vieilles barbes de service, ensuite en guise de pied de nez à l’endroit des puristes du jazz, incapables d’admettre qu’un musicien puisse transgresser les sacro-saints interdits de leurs minuscules tiroirs mentaux. Modernistic se réfère encore à Debussy par son atmosphère terriblement française et, en même temps, complètement “d’ailleurs”. Il y a là quelque chose de follement onirique et de furieusement enraciné dans cette terre du Nord, entre le ciel et l’eau – une île probablement.

On pourrait même avancer que le Swing Concerto lui aussi, œuvre ambitieuse qui marie sans heurt l’influence de la musique française moderne et celle des cordes tziganes, l’exotisme voire, dans sa dernière partie, le technicolor hollywoodien, se situe dans une semblable lignée. Chant du cygne, testament à la foisonnante richesse, il sonne déjà comme un adieu. A part Pierre Darrieux, nul ne le reprit jusqu’au 13 décembre 1998, quand le violoniste Guillaume Sutre le donna avec le “Jeune Orchestre Symphonique”, direction Henri Vachey, à l’auditorium de Douai…

Violoniste du siècle, Michel Warlop ? Pourquoi pas. Simplement, ceux qui lui prédisaient un si bel avenir n’ont pas songé un seul instant qu’on pouvait l’être aussi en jouant du jazz…

Daniel NEVERS

© 2013 Frémeaux & Associés

On peut également entendre le violon de Michel Warlop sur les volumes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11 et 12 de l’Intégrale Django Reinhardt, ainsi que dans plusieurs autres recueils Frémeaux. En particulier ceux consacrés à Mireille (FA-043), Danielle Darrieux (FA-5041), Johnny Hess (FA-5054), où sa contribution est parfois des plus modestes. Il se trouve davantage mis en valeur dans l’Intégrale des titres gravés par Irène de Trébert entre 1941 et 1944, la plupart du temps avec des contingents de l’orchestre Raymond Legrand (FA-056).

MICHEL WARLOP

It’s been a long time since critic Alain Gerber pointed out the paradoxical nature of jazz violin in contrasting “violinist jazz” – with its attachment to the values of ancient Europe and so-called “classical” music – with “violin jazz”, played on an instrument which, like others, had adapted perfectly to the language and syntax of Afro-American music. “Violinist jazz” would group musicians like Joe Venuti, Eddie South, Stéphane Grappelli, the young Helmut Zacharias and even (somewhat ambiguously) Svend Asmussen, whereas “violin jazz” would open its arms to Juice Wilson, Ray Nance, Stuff Smith, Jean-Luc Ponty or Didier Lockwood. But to which group did Michel Warlop belong? In 2011, Pierre Guingamp produced a weighty, serious, well-documented, first-of-its-kind study devoted to Warlop (at last!); Ponty wrote its preface, and the book was published in France by L’Harmatan under the title Michel Warlop – Génie du violon swing. Nobody ever really knew where to situate Michel Warlop, unless in some box between the two categories above. Warlop was designated as unclassifiable, and therefore doomed to oblivion. It was all the easier because he died so young. Not finding any room for him in a little mental “box” – so practical – is a totally unacceptable sin. C’est la vie: the “unclassifiable” easily join the condemned.

According to legend, as they say, in the beginning was the trumpet or, more precisely, the cornet. Around New Orleans there’s always someone ready to spin you the yarn which has it that, yes, in the beginning, there was above all the violin, which conducted all the other instruments, and that the trumpet (or cornet) had the devil of a time putting the devil’s instrument – the fiddle – in its place. But the cornet managed it in the end, along with trumpeters from New Orleans who were the biggest roosters in the chicken-run: Buddy Bolden, Bunk Johnson, Emmanuel Perez, Freddy Keppard, Joe Oliver, “Papa” Jack Laine and a few others… At the other end of the chain – it was actually the beginning of another – there was, thanks to destiny, the King of Kings: Louis Armstrong in person. In the most creative decade – the Twenties – of an iron century, Armstrong exploded. And at the same time, there was also a highly innovative pianist by the name of Earl Hines, considered to be the inventor of a “trumpet-piano style” because he could reproduce the accents of a trumpet with his keyboard. Naturally, he played with Louis Armstrong; in around 1927/28 the pair even formed one of the most beautiful duos that jazz has ever known. If you care to challenge that statement, just take a listen to Volumes 4 & 5 of the Complete Armstrong set released by Frémeaux & C° (FA 1354 & 1355).

On the other side of the Atlantic in those same Twenties, a young man with a (rather important) gift for music was enjoying himself at the Conservatories in Lille and Paris – he won their prizes for excellence –, and he was just starting to listen to the first Armstrong/Hines records imported into France. He listened to other musicians too – Bix Beiderbecke, Frankie Trumbauer, Eddie Lang, Joe Venuti. In other words, he liked “jazz”. He also already had behind him a tidy little career as a classical performer, because he was, after all, quite gifted: in 1927 he played a concert in his native Douai – pieces by Fauré, Debussy, Borodin and Lalo – and the year after, he gave a concert at Pleyel in Paris, having obtained the Violin Prize from the Conservatoire National de Paris. He had also just been appointed First Solo Violin and Assistant Conductor of the “Concerts Robert Siohan” Orchestra, plus First Violin with Walter Straram… But jazz… Jazz was how his youthful fire and enthusiasm, just when his destiny seemed mapped out for him, plunged him body and soul into a great adventure. There were some who never forgave him: Victor Gallois, for one, the winner of a Prix de Rome and his Master & Commander (as he was for Dutilleux also); nor was he forgiven by Piero Copolla, the composer and renowned conductor – also the executive director (since the early twenties) of the “Compagnie Française du Gramophone” – who saw Warlop as one of the four or five great violinists of the century… But Copolla would often give Warlop a hand with his big-band forays in the early Thirties, providing him with a number of recording-sessions in which he accompanied singers both female and male (Germaine Sablon, Eliane de Creus, Cora Madou for the former, Maurice Chevalier, Aimé Simon-Girard, Jean Sorbier, Ole Cooper, Robert Burnier or Petit Mirsha for the latter.)

Of course, the violin wasn’t the instrument one most often ran into in jazz: “Violins are for girls”, said a few cretins without blushing. But Michel Warlop wasn’t the first violinist to try his hand at this new music anyway. In America, in the Twenties, Joe Venuti and Matty Malneck (from Paul Whiteman’s band) – “white” players –, plus Eddie South, ‘Juice’ Wilson, Darnell Howard – “black” players – had already done some serious trail-blazing. Even in France, Stéphane Grappelli, Michel’s elder by three years, was already in the vanguard: inspired first by Venuti, he later turned to Eddie South, and played and recorded with both over the course of a long career. In the end he forged a style that was all his own, a model of balance, swing and elegance. Most of those musicians, in any case, practised the violin like all well-educated violinists are supposed to do, even if Venuti would unashamedly slide his instrument between the horsehairs and the stick of his bow, or Wilson tear the place up a bit with the help of electricity (cf. Violon Jazz – Frémeaux FA 052). But not Michel Warlop. It wasn’t that he lacked an education, (on the contrary), nor was it that he never listened to the others (he did, albeit with a vague feeling of frustration, particularly with regard to the refinement in the playing of his friend Stéphane); but Michel Warlop’s worried nature, his nervousness and, probably, his conception of jazz too, incited him to make his instrument sound different – a little like Earl Hines did with his piano. To resume, Michel Warlop invented a “trumpet-violin style” with just that little bit of “tormented soul” lyricism which it needed…

Born in Douai (January 23rd 1911), an industrial mining-town in the north of France –its music-conservatory was founded in 1806, which makes it the second-oldest in France – Michel Warlop lived for only thirty-six years (he passed away on March 6th 1947, in Bagnères-de-Luchon at the other, greener end of the country). He scarcely ever travelled abroad, limiting himself to a few escapades in Belgium a few miles away from Douai. He also spent some time in Germany, in 1940-41, but that was an experience he would have preferred to forget… The Germans sent their thirty year-old prisoner back quite quickly: he wasn’t in very good shape, and they probably wondered how on earth he’d managed to get into the army in the first place. Warlop brought back with him his musical setting for the Jean Mariat poem Le Noël du Prisonnier – [“The Prisoner’s Christmas” indeed!] – recorded on February 17th 1942 by Jean Davy (who recited it) with the composer conducting the orchestra. Those with an eye for detail will appreciate the information that it was a 78rpm record for Columbia (DFX-240), which was bought by only 775 people in the course of the next five years. It’s known that 232 copies were scrapped (of a total pressing of 1700). Miserable.

Travel doesn’t necessarily do much for the old, nor for the wise; provided that one’s head is a good one, however, and not yet overdone, it so happens that the young can discover more beautiful territory without going anywhere other than through their own inventiveness… The young Michel Warlop, guided by the firm hand of his mother, an amateur pianist, became a machine built for competitions, and he won several medals in Lille before he naturally left his family’s pâtisserie in the centre of Douai. His father, they say, was an exceptionally strong man who didn’t much like his son practising during the day – it annoyed his customers –, and who drank like a fish. He also slept little and survived his son until a ripe old age. Michel Warlop went elsewhere to pursue his career and its honours, i.e. to Paris where, as destiny would have it, he crossed paths with the devil in the shape of what they didn’t yet call “that decadent Jewish Negro music” known as “jazz”…

By the end of the Twenties, Paris – particularly in Montmartre, Montparnasse and around the Champs-Elysées – had a whole bunch of clubs which specialized in that kind of exoticism. They were Michel’s haunts, and there he met both visiting Americans and the first representatives of French jazz: Philippe Brun, Pierre Allier, Alex Renard, André Ekyan, Alix Combelle, Alain Romans, Stéphane Mougin, Lucien Moraweck, Léo Vauchant, Roger Fisbach, Guy Paquinet… But not Django, who, at the time, was working in places which featured a rather different kind of music, i.e. “musette”. Grappelli, on the other hand, was very much in evidence in the jazz family, even though he didn’t need his arm twisted to play with a tango orchestra. It was even in one such band, at a 1929 recording-session, that he was spotted by the “Sublime Grégor”, who promptly hired him, not as a pianist (which Grappelli claimed to be), but indeed as a violinist. The Armenian Krikor Kélékian – a dilettante of some genius, who didn’t play any instrument but was a born salesman when it came to selling himself (albeit under the spelling “Grégor”) – was leading his “Grégoriens” at the time, no doubt the best French big-band (and definitely a rather cosmopolitan outfit, as it included – apart from Grégor himself – a Swiss saxophonist, a Scottish drummer and several White Russian émigrés!)

Michel and Stéphane quickly discovered they had enough in common to move into a little apartment in Montmartre. Where the violin was concerned, however, they differed: while they both had admiration for Heifetz, Grappelli had a weakness for Joe Venuti, whereas Warlop swore by Eddie South, whose lovely records from 1927-28 had just been released in Europe. Sometime in the mid-Seventies, Stéphane would go so far as to say that “in those days” (i.e. 40 years previously), there were only three violinists who could play “hot”: Venuti, Michel Warlop, and himself. Nobody could make him admit that Eddie South was also a serious contender: “Eddie, I only met him at the end of the Thirties when we recorded together.” Yet South was playing in Paris early in 1929, and even made a record there; it was certainly then that Warlop must have heard him and taken a shine to his playing, and it’s hard to believe that Michel didn’t mention it to Stéphane. It’s even harder to believe that someone as curious as Grappelli wouldn’t jump at the chance to go and hear him for himself, if only for an evening…

The short-film Un Opéra-Jazz, made early in 1930 – shot onstage at the Empire Theatre in Paris – proves that Grappelli was indeed a violinist then, not a pianist. One of the two other violins in this short-film is definitely René Cézard, and the other is perhaps Sylvio Schmidt – but not a sight of Warlop anywhere. Michel only joined the group in the spring, as shown by four sides he recorded for Columbia (Je chante sous la Pluie, Le Rugissement du Tigre…) on April 29th 1930. They were no doubt his first sides. As a result, Grappelli found himself behind a piano, the instrument, incidentally, which he said he always preferred to the violin. Might he have been piqued at it, all the same?

The orchestra played its summer season in Argentina, although Michel, no doubt due to his tender years, didn’t make the trip. He found a job in Paris with the Jazz Pathé-Natan group, and probably recorded with it (although not taking any solos). You can get a glimpse of him with the group at the beginning of the Pathé film Chacun sa Chance, which was made that autumn. For some, the film’s title – it means “Everyone gets lucky” – was an omen: Warlop was only an extra, but the film was the first for Jean Gabin, and the first for Jean Sablon (who became a singing-star, not a film-star like Gabin); as for the props man in the film, the nice-guy blunderer, it was Charles Trenet, who became probably the best-known of them all… At the end of 1930, once the Gregorians had returned, Michel cut a few (rare) sides for the ephemeral Aeolian label. As for Grégor, he was responsible for a serious car-accident and, injured, he thought it was wiser to skip the country. He went to Argentina.

1931 was when Michel Warlop did his military service – and he was (musically) drafted into the 1st Infantry Regiment. The following year, he was to play a brief engagement at The Lido with the orchestra of a mysterious Harry Reser (no relation to the famous American banjo-player), and also took part in a record-session at the Ultraphone studios in Montparnasse. He went back in 1933, as Ultraphone had signed an exclusive contract with Grégor’s new ensemble – he’d returned from exile after being granted amnesty – and this is where the present anthology begins, with the Fantaisie Grégorienne composed and arranged by Warlop – in the spirit of “symphonic jazz” and Ellington combined – with the violin solo played by the tune’s composer at no extra charge.

Musically speaking, spring 1933 was an excellent vintage for the local jazz stars – Warlop, Grappelli, Pierre and Roger Allier, Ekyan, Fisbach, Alix Combelle, Moraweck, Mougin, Roger Grasset… – and the crop was equally varied. The music even found its way into the film of a new, “modern” version of the famous French play Miquette et sa Mère, with Blanche Montel and Michel Simon (cf. Ciné Stars – Frémeaux FA 063). Records weren’t selling well in those critical times, however: bookings were rare, and even the previous decade’s most famous clubs were closing their doors. The Gregorians just had the time to hightail it to the coast (the Basque country) for their summer season, but it didn’t last long, as Grégor was obliged to disband his orchestra even before they returned to Paris. A final attempt in 1934 – with other musicians, but no recordings – was just as unsuccessful, and The Sublime Krikor “Grégor” Kélékian left the jazz scene for good.

The end of 1933 was lively, even so, with ex-Gregorians recording many sides – they were earning a living, if not distinction –, most often with Warlop and Moraweck leading them, for Etoile, the Editions de Paris, the institutional SEDOEM (which supplied dance-schools with wax)… More interesting than those were the sides made under the name of the “Chicago Syncopators” (sic), produced by black American composer Henry Matéo (alias H. McKnight) under his own label. My Gal Sal and Harlem Hurricane contain nice contributions from the violinist, whose identity finally appeared – apparently for the first time – in print on the labels. A rather similar group, no doubt, was the one which recorded (for an unidentified firm), a mysterious Dr. Swing at the end of 1933 or early in 1934. In 1934-35, apart from his debuts as a big-band leader in his own right and his first records under his own name with a medium-sized group (All For the Swing, Crazy Fiddle), Michel frequently responded to calls from other bands for certain gigs and recording-sessions: the ‘Jazz du Poste Parisien’ (led by Moraweck) and the ‘Jazz Patrick’ (alias Guy Paquinet) were groups containing several ‘Gregorians’ alumni, and sometimes Django and Grappelli, who were themselves the founders of an astonishing (string) ‘Quintette du Hot Club de France’, not yet a regular outfit… Warlop himself made sure he commandeered both Django and Grappelli for his own records (Presentation Stomp, Blue Interlude). In March 1935, his orchestra accompanied Coleman Hawkins at the Salle Pleyel and also in the studios of the Compagnie du Gramophone, but Warlop didn’t play on them.