- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

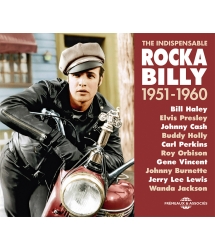

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

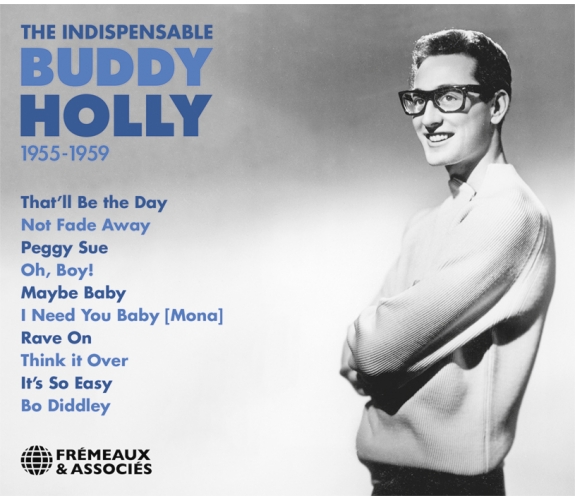

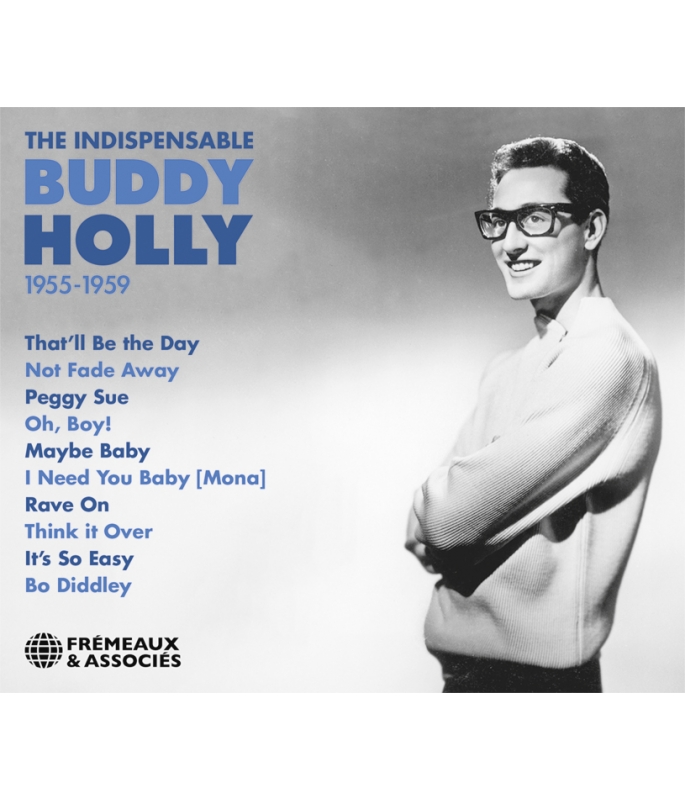

1955-1959

BUDDY HOLLY

Ref.: FA5762

EAN : 3561302576220

Direction Artistique : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 2 heures 13 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

1955-1959

Buddy Holly a surgi du Texas en 1957 comme le vent nouveau du rockabilly puis du rock tout court, montant au numéro un avec une série de succès internationaux raffinés comme « Peggy Sue ». Les Beatles ont construit leur style en apprenant ses morceaux, et le premier succès des Rolling Stones était une chanson de lui. Bruno Blum raconte ici l’histoire d’une légende parmi les légendes : chanteur dont la signature des « hoquets » rend son style inimitable, guitariste soliste, brillant compositeur mélodiste, il fut une révélation promise à une longue carrière au sommet. Seize mois plus tard, son avion s’écrasait, le tuant sur le coup à l’âge de vingt-deux ans. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

In 1957 Buddy Holly emerged out of Texas as the new wind of first, rockabilly, then rock, full stop, going directly to Number One with a series of refined international hits such as “Peggy Sue.” The Beatles built their early style learning his tunes, and the first Rolling Stones hit was a Buddy Holly cover version. Bruno Blum here tells the story of a legend among legends: a singer whose ‘hiccups’ signature made his style inimitable. A lead guitarist and a brilliant melody composer, he was a revelation — promised for a long career at the top. Sixteen months later, his plane crashed, killing him on the spot at the age of twenty-two. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

DISC 1 - 1955-1957 : MEMORIES • BABY LET’S PLAY HOUSE • MOONLIGHT BABY • MIDNIGHT SHIFT • DON’T COME BACK KNOCKIN’ • BLUE DAYS, BLACK NIGHTS • LOVE ME • ROCK AROUND WITH OLLIE VEE • I’M CHANGIN’ ALL THOSE CHANGES • THAT’LL BE THE DAY • GIRL ON MY MIND • TING-A-LING • MODERN DON JUAN • YOU ARE MY ONE DESIRE • GONE • HAVE YOU EVER BEEN LONELY • I’M LOOKING FOR SOMEONE TO LOVE • THAT’LL BE THE DAY • WORDS OF LOVE • MAILMAN BRING ME NO MORE BLUES • NOT FADE AWAY • EVERYDAY.

DISC 2 - 1957-1958 : READY TEDDY • PEGGY SUE • I’M GONNA LOVE YOU TOO • OH, BOY! • AN EMPTY CUP (AND A BROKEN DATE) • ROCK ME MY BABY • YOU’VE GOT LOVE • MAYBE BABY • LAST NIGHT • SEND ME SOME LOVIN’ • IT’S TOO LATE • TELL ME HOW • LITTLE BABY • (YOU’RE SO SQUARE) BABY I DON’T CARE • LOOK AT ME • I NEED YOU BABY [MONA] • RAVE ON • WELL… ALL RIGHT • FOOL’S PARADISE • TAKE YOUR TIME.

DISC 3 - 1958-1959 : THINK IT OVER • IT’S SO EASY • HEARTBEAT • EARLY IN THE MORNING • NOW WE’RE ONE • PEGGY SUE GOT MARRIED • THAT’S WHAT THEY SAY • WHAT TO DO • CRYING, WAITING, HOPING • THAT MAKES IT TOUGH • LEARNING THE GAME • BO DIDDLEY • BROWN-EYED HANDSOME MAN • BABY WON’T YOU COME OUT TONIGHT • WAIT TILL THE SUN SHINES NELLIE • SMOKEY JOE’S CAFÉ • TRUE LOVE WAYS • IT DOESN’T MATTER ANYMORE • RAINING IN MY HEART • MOONDREAMS.

(DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : BRUNO BLUM)

1956-1962

ELVIS PRESLEY, BILL HALEY, ROY ORBISON, GENE...

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1MemoriesBuddy HollyBob Montgomery00:02:191955

-

2Baby, Let's Play HouseBuddy HollyArthur Gunter00:02:271955

-

3Moonlight BabyBuddy HollyDon Guess00:01:531955

-

4Midnight ShiftBuddy HollyJimmy Ainsworth00:02:111956

-

5Don't Come Back KnockinBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:141956

-

6Blue Days, Black NightsBuddy HollyBen Hall00:02:041956

-

7Love MeBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:071956

-

8Rock Around With Ollie VeeBuddy HollyCurtis Sonny00:02:121956

-

9I'M Changin' All Those ChangesBuddy HollyDon Guess00:02:131956

-

10That'll Be The DayBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:291956

-

11Girl On My MindBuddy HollyDon Guess00:02:171956

-

12Ting-A-LingBuddy HollyAhmet Ertegun00:02:411956

-

13Modern Don JuanBuddy HollyDon Guess00:02:391956

-

14You Are My One DesireBuddy HollyDon Guess00:02:221956

-

15GoneBuddy HollyEugene Rogers00:01:151956

-

16Have You Ever Been LonelyBuddy HollyPeter De Rose00:01:211956

-

17I'M Looking For Someone To LoveBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:01:571957

-

18That Will Be The DayBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:161957

-

19Words Of LoveBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:01:551957

-

20Mailman Bring Me No More BluesBuddy HollyRuth Roberts00:02:121957

-

21Not Fade AwayBuddy HollyJerry Allison00:02:211957

-

22EverydayBuddy HollyJerry Allison00:02:071957

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Ready TeddyBuddy HollyRobert Blackwell00:01:311957

-

2Peggy SueBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:301957

-

3I'M Gonna Love You TooBuddy HollyJoe Mauldin00:02:131957

-

4Oh! BoyBuddy HollyNorman Petty00:02:071957

-

5An Empty Cup (And A Broken Date)Buddy HollyNorman Petty00:02:131957

-

6Rock Me My BabyBuddy HollyShorty Long00:01:501957

-

7You've Got LoveBuddy HollyJonnhy Wilson00:02:081957

-

8Maybe BabyBuddy HollyNorman Petty00:02:021957

-

9Last NightBuddy HollyNorman Petty00:01:541957

-

10Send Me Some Lovin'Buddy HollyJohn Marascalo00:02:351957

-

11It's Too LateBuddy HollyChuck Willis00:02:231957

-

12Tell Me HowBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:001957

-

13Little BabyBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:01:571957

-

14(You're So Square) Baby I Don't CareBuddy HollyJerry Leiber00:01:371957

-

15Look At MeBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:061957

-

16Mona (I Need You Baby)Buddy HollyEllas Mc Daniel00:02:281957

-

17Rave OnBuddy HollySonny West00:01:491958

-

18Well All RightBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:141958

-

19Fool's ParadiseBuddy HollyNorman Petty00:02:311958

-

20Take Your TimeBuddy HollyNorman Petty00:01:581958

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Think It OverBuddy HollyNorman Petty00:01:461958

-

2It's So EasyBuddy HollyNorman Petty00:02:111958

-

3HeartbeatBuddy HollyBob Montgomery00:02:091958

-

4Early In The MorningBuddy HollyBobby Darin00:02:071958

-

5Now We're OneBuddy HollyBobby Darin00:02:041958

-

6Peggy Sue Got MarriedBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:061959

-

7That's What They SayBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:121959

-

8What To DoBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:01:541959

-

9Crying, Waiting, HopingBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:141959

-

10That Makes It ToughBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:271959

-

11Learning The GameBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:111959

-

12Bo DiddleyBuddy HollyEllas Mc Daniel00:02:221959

-

13Brown-Eyed Handsome ManBuddy HollyChuck Berry00:02:041959

-

14Baby Won't You Come Out TonightBuddy HollyDon Guess00:01:541959

-

15Wait Till The Sun Shines, NellieBuddy HollyAndrew Sterling00:01:551959

-

16Smokey Joe's CafeBuddy HollyMike Stoller00:02:131959

-

17True Love WaysBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:481958

-

18It Doesn't Matter AnymoreBuddy HollyPaul Anka00:02:041958

-

19Raining In My HeartBuddy HollyBryant Boudleaux00:02:471958

-

20MoondreamsBuddy HollyNorman Petty00:02:401958

fa5762 Buddy Holly

THE INDISPENSABLE

BUDDY

HOLLY

1955-1959

That’ll Be the Day

Not Fade Away

Peggy Sue

Oh, Boy!

Maybe Baby

I Need You Baby [Mona]

Rave On

Think it Over

It’s So Easy

Bo Diddley

The Indispensable Buddy Holly 1955-1959

Par Bruno Blum

John portait des lunettes en écailles et quand il y avait des filles, il les planquait. Mais quand Buddy est arrivé il s’est dit, ah oui, moi aussi je peux en porter. Et puis l’autre raison qu’on avait de l’aimer c’est qu’il écrivait ses chansons lui-même. Elvis ne composait pas, on l’adorait mais il n’écrivait pas. Buddy composait, jouait, et il jouait aussi les solos. Il était autonome, et c’est ce qu’on voulait faire aussi. La première chose qu’on n’arrivait pas à refaire, c’était le début de That’ll Be the Day. Et je crois que c’est George qui a réussi à le jouer.

- Paul McCartney

Elvis Presley est devenu un phénomène début 1956. Dans un contexte pesant de ségrégation raciale, l’adoption de plus en plus massive de la musique afro-américaine par les adolescents de l’après-guerre provoqua un choc culturel sans précédent dans le pays : le rock de Fats Domino, Ray Charles (écouter ici Early in the Morning), les Coasters/Robins (écouter ici une maquette de leur Smokey Joe’s Café) puis Little Richard (écouter ici Ready Teddy et Send Me Some Lovin’), Bo Diddley (écouter ici Mona, la composition de Buddy Holly Not Fade Away très marquée par Diddley et sa version à succès de Bo Diddley), Chuck Berry (écouter ici Brown-Eyed Handsome Man) avaient du succès. Ils inspirèrent nombre d’artistes blancs de country à jouer un dérivé du rock afro-américain originel, créant ainsi le style rockabilly dont Gene Vincent, Bill Haley et Elvis Presley étaient les fers de lance. Buddy Holly fut l’un de ces jeunes enthousiastes. Il incorpora comme eux des guitares country au rock, qui devint rockabilly. Holly avait fait ses débuts dans un duo hillbilly (country) avec Bob Montgomery ; appelée « western music » chez lui au Texas, la country était populaire mais, impressionné par un concert d’Elvis, il opta à son tour pour le rockabilly — le rock blanc, mélange de rock noir et de hillbilly blanc. Mais comme Roy Orbison, un autre artiste de rockabilly, Buddy Holly avait une vraie ambition de compositeur, de mélodiste et il créa un style qui n’appartient qu’à lui. Il se démarqua vite du pur rockabilly. That’ll Be the Day, Everyday, Peggy Sue, Oh Boy, Rave On, Maybe Baby, Not Fade Away et Words of Love comptent parmi ses compositions les plus connues. Il y exprime les tourments et joies de l’amour.

En Europe, son style mélodique et inspiré deviendrait, avec celui des Everly Brothers, une influence centrale sur les jeunes Beatles, qui enregistrèrent une maquette de That’ll Be the Day, son Crying, Waiting, Hoping à la BBC et surtout son Words of Love le 18 octobre 1964 (album Beatles For Sale, paru le 4 décembre 1964). Holly marqua aussi les Rolling Stones débutants, qui gravèrent Not Fade Away ; paru chez Decca le 21 février 1964, ce premier grand succès lança le groupe. Buddy Holly s’accompagnait à la guitare avec un style original. Il participa ainsi largement à définir l’orchestration fondamentale du rock classique des années à venir : chanteur-guitariste, deuxième guitariste, basse et batterie. Après quelques échecs commerciaux, d’abord en country sur scène puis en rock avec la marque Decca, la publication de That’ll Be the Day, sorti sous le nom des Crickets pour des raisons contractuelles le 27 mai 1957, fut une révélation; en septembre, la chanson était numéro un en Angleterre et aux États-Unis. La sortie le 23 septembre de Peggy Sue, son plus grand classique, le propulsa vers de nouveaux sommets à l’âge de vingt ans. Il lui restait seize mois à vivre.

Lubbock, Texas

Charles Hardin Holley dit Buddy Holly est né le 7 septembre 1936 (à 15h30) au 1911 Sixth Street à Lubbock, Texas, au cœur d’une très violente crise économique mondiale. Lubbock a toujours été l’une des villes les plus conservatrices et religieuses du pays, avec port d’arme très libre et une ségrégation raciale stricte. L’alcool y est resté strictement interdit jusqu’en 1972. Surnommé « Buddy », Charles Holley avait deux frères et une sœur.

Ses parents étaient Laurence Holley dit L.O., un cuisinier texan devenu laboureur pendant la Grande Depression, et Ella Drake (dont le père avait du sang cherokee, et dont la famille a des liens avec l’explorateur du XVIe siècle Francis Drake).

Travailleur, L.O. était aussi diacre d’un temple radical Tabernacle Baptist. Il était très pauvre et Buddy rejoint les Scouts. Les Holley déménageaient dans des cabanes de planches. Ils jouaient tous de la musique, sauf L.O., et vers l’âge de cinq ans Buddy remporta un prix de cinq dollars en jouant d’un violon-jouet.

Un déménagement de trop lui fit perdre tous ses amis et il se réfugia dans la musique en prenant des cours de piano. Déçu, il adopta la guitare et son père lui offrit une Harmony d’occasion. En ce temps-là, la musique country réunissait des gens de tous les âges, et unissait les Texans blancs bien-pensants : folk, ballades, chansons de cowboys, de feux de camp. Buddy appréciait la Carter Family, Woody Guthrie, Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Snow, Roy Rogers et les Sons of the Pioneers, Gene Autry, etc. Il fréquentait les bals ruraux et écoutait les émissions de radio country en direct du Grand Ole Opry et du Louisiana Hayride. L’accès des Blancs aux musiques afro-américaines était totalement bloqué par la ségrégation et le blues afro-américain était considéré promouvoir le péché. L’apparition de Hank Williams montrait un artiste vulnérable, sensible, des traits que l’on retrouvera dans l’œuvre de Buddy Holly.

La country du Texas de cette époque était dominée par le style « western swing » de Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys influencé par les musiques swing des dancehall noirs. Ce style western contrastait avec les autres branches de la country. En précurseur du rockabilly, l’irrésistible country boogie ou « hillbilly boogie » des années 1940 avait été le véritable acte fondateur du rock blanc. Dérivé du western swing, il pulsait dans l’après-guerre en plaquant déjà des guitares country carrées, incisives sur le boogie woogie et le swing noir.

Buddy retourna à Lubbock et revint à la J. T. Hutchinson Junior High School. Il maitrisa vite le banjo (un banjo européen à quatre cordes) et chanta les harmonies vocales bluegrass avec un copain de classe guitariste, Bob Montgomery. Il renoua aussi avec Don Guess, son futur bassiste et co-compositeur, et Jerry Allison, futur batteur et ami. Il commença à se produire en duo country avec Jack Neal (qui avait composé avec Don Guess) sous le nom de Buddy and Jack. Il fut un bon élève au lycée malgré sa très mauvaise vue (20/800) et commença à porter des lunettes en 1954. Excellent en anglais, il aidait son frère charpentier à construire des toits ; Buddy était un garçon sympathique, serviable et sûr de lui. Il aimait dessiner et la gravure sur cuir. Il chantait avec Bob Montgomery et fréquentait Echo McGuire, une étudiante de famille aisée qui fréquentait l’austère Church of Christ (où toute musique et danse étaient formellement interdites). À seize ans Buddy séduit la jeune femme avec l’accord des parents — pour une relation « amicale » platonique. Le mode de vie pieux et très sage de Buddy contrastait avec celui d’autres rockers de sa génération comme Little Richard ou Jerry Lee Lewis.

Hillbilly & Western

Le 4 novembre 1953, Buddy and Jack furent invités à chanter quatre chansons sur KDAV, qui était la nouvelle, première et seule station 100 % country du pays. Leur succès leur assura une émission de trente minutes en direct tous les dimanches, où quelques titres hillbilly, dont Memories, furent enregistrés plus tard. En quelques jours, ils sont devenus des vedettes « hillbilly & western » au Texas. Montgomery les rejoint bientôt.

En dépit de la prohibition Buddy goûta au whisky de contrebande mais il ne supportait pas l’alcool. Il commença à fumer des Salem à seize ans. Admirateur du guitariste de jazz comme du compositeur Les Paul, à l’automne 1954 il acquit une Gibson Les Paul Gold Top dorée. Il se cachait dans sa voiture pour écouter les stations de radio de Louisiane comme KWKH ou du Tennessee qui diffusaient du blues, et appréciait secrètement les musiques noires, au risque d’une correction musclée : en 1954-55 au Texas ses favoris Bo Diddley, les Coasters, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James et sa grande influence Hank Ballard ne pouvaient pas être écoutés en public par un Blanc. Écouter et aimer des musiques noires était un début de rapprochement racial et des artistes comme les Drifters, Nat « King » Cole, Louis Jordan et Fats Domino étaient appréciés par nombre de jeunes Blancs. Buddy commença à fréquenter les limites du quartier noir. Il y rencontra des musiciens de blues et décida qu’il ne soutiendrait plus la ségrégation, un engagement osé. Il appela même son chat Booker T. Washington ! Il commençait à être connu dans la région. Le duo joua en première partie de vedettes de la country au Cotton Club près de Lubbock, où les Noirs étaient admis car le Cotton était situé hors de la ville. Le présentateur de leur émission de radio, « Hi Pockets » Duncan, devint alors leur manager et leur assura des engagements au Clover Club d’Amarillo. Ils ont été rejoints par Sonny Curtis, un guitariste soliste avec qui Buddy partageait son goût secret pour le blues.

Elvis

Buddy Hall, disc jockey de KDAV, fit découvrir à ses auditeurs le premier disque d’Elvis Presley, qui réunissait un chant expressif, marqué par la culture afro-américaine, une excitante rythmique de blues et une guitare country caractéristique. Buddy et Sonny adoraient eux aussi.

Le 2 janvier 1955 ils assistèrent à un concert de la vedette montante du pays. Son spectacle révolutionnaire, où il se mouvait sans retenue, et sa musique rockabilly brisaient tous les codes de la country respectable. Malgré ses parents terrifiés, la jeunesse succombait au charme d’Elvis et Buddy Holly adopta aussitôt son style.

Sonny Curtis laissa tomber le violon (Memories) et apprit la guitare dans le style de Chet Atkins et Scotty Moore, le guitariste d’Elvis. Don Guess abandonna la guitare steel et passa à la contrebasse. Le style de Buddy fut instantanément transformé. Il se mit à s’agiter sur scène, cessa de chanter avec retenue comme tant de chanteurs de country le faisaient. Il semblait soudain habité par un feu intérieur. Un rocker était né. Et son groupe métamorphosé était soudain en forte demande.

Le 13 février 1955, Buddy & Bob ont joué en première partie d’Elvis Presley au Fair Park Coliseum de South Plains Fair à Lubbock. Elvis et Buddy partageaient des goûts musicaux et devinrent amis. Elvis était une vedette mais il n’était pas encore le phénomène générationnel qu’il deviendrait un an plus tard avec l’aide des disques RCA. Buddy enregistra bientôt une maquette de Baby Let’s Play House, un blues dont il copia la version rockabilly gravée par Elvis. Il jouait plusieurs fois par semaine et ses cachets augmentaient. 1955 est aussi l’année où Bill Haley a connu un énorme succès avec « Rock Around the Clock » ; des artistes afro-américains comme les Penguins, Fats Domino, Frankie Lymon, Johnny Otis avaient du succès et Chuck Berry a sorti ses premiers chefs-d’œuvre, sans oublier Little Richard. En décembre, l’hymne rockabilly de Carl Perkins « Blue Suede Shoes » a été enregistré au studio Sun. Et Elvis continuait à donner à la jeunesse blanche une excitation, un enthousiasme et une liberté que les générations précédentes n’avaient jamais connus.

À dix-huit ans Buddy a passé l’été à travailler comme terrassier et il a rencontré Little Richard. Buddy est devenu rebelle avec ses parents et la police. La nuit il partait hors de la ville jouer seul avec les groupes de rock dans des zones éloignées de l’ordre religieux urbain. Les filles criaient quand il chantait du rock et le temps de l’abstinence était terminé. Il menait une double vie, étudiant pieux le jour et rocker la nuit.

Le 14 octobre il joua en première partie de Bill Haley et fut repéré par Eddie Crandall. Crandall suggéra au manager d’Elvis de s’occuper de lui mais le Colonel Parker, trop occupé, lui répondit de s’en charger lui-même. Le « rock ‘n roll », terme issu du vocabulaire noir, était maintenant à la mode et les maisons de disques cherchaient des artistes de rockabilly capables de concurrencer Elvis Presley. Paul Cohen chez Decca offrit un simple contrat d’enregistrement sans rien promettre de plus. Buddy emprunta mille dollars à son frère Larry, acheta une Fender Stratocaster sunburst marron et des habits voyants : manteau rouge, chaussures de daim bleu, gilet chartreuse… la première séance de studio sous la direction d’Owen Bradley eut lieu à Nashville début 1956 avec l’excellent Sonny Curtis comme guitariste soliste (après le décès de Buddy, Sonny le remplacera au sein des Crickets). Alors que Presley parvenait au statut de superstar, Decca ne croyait pas en Buddy et après quelques disques sans promotion, une tournée — et une première version non satisfaisante de That’ll Be the Day en juillet, Buddy s’est disputé avec Paul Cohen plusieurs fois car il ne le laissait pas jouer sa musique comme il l’entendait (disque 1, titres 4-14). Comme l’an passé, Buddy a passé l’été à aider son père et son frère Larry, un ancien Marine, cette fois à poser des tuiles et de la charpenterie. Elvis, lui, est resté au n°1 d’août à décembre. Buddy était inconnu en dehors de la région, où ses concerts nécessitaient que Larry le protège des garçons jaloux ; il était aussi devenu Buddy Holly (et non Holley) en raison d’une faute d’orthographe sur le contrat. Après une troisième séance en novembre et de nouvelles disputes avec Cohen, son contrat lui a été rendu en janvier 1957.

La grande mode du rock de 1955-1957 subissait un retour de flamme. Une insidieuse campagne de dénigrement venue des forces conservatrices, puritaines et racistes de l’Amérique frappait.

Norman Petty

Au printemps de 1956 Buddy Holly a rencontré Norman Petty, un organiste assez banal, louche, efféminé bien que marié à une pianiste et chanteuse, Violet Ann « Vi » Petty. C’est avec le guitariste Jack Vaughn que Norman Petty et Vi avaient obtenu en 1954 un succès chez Columbia, une version de « Mood Indigo ». Ils donnaient des concerts sans envergure dans tout le pays. Créateur médiocre, Petty était un bon ingénieur du son et avec l’argent du disque il avait construit un petit studio d’une seule piste à Clovis, une bourgade du Nouveau-Mexique perdue dans les champs de coton et de blé. Il s’en servait pour répéter et enregistrer avec son épouse, une femme anxieuse totalement sous sa domination. Le studio accueillait aussi des clients. Petty avait enregistré une maquette pour Jimmy Self, et lui avait ensuite obtenu un contrat avec RCA, la marque d’Elvis. À vingt-neuf ans, Petty était un Baptiste bigot qui ne quittait pas sa Bible et demandait des prières aux musiciens, qui s’exécutaient en cercle après les bonnes prises; boire, fumer ou jurer était interdit chez lui. À la fois avare et généreux, il accueillait les clients dans le confort, le frigo était toujours plein et il n’était payé qu’une fois l’enregistrement fini (et non en fonction du temps passé). En échange de ses apparentes largesses, ses clients signaient des contrats lui abandonnant une part des droits d’auteur, même quand il n’avait rien composé (une pratique d’éditeur, courante alors). Petty avait déjà enregistré chez lui la maquette de « Ooby Dooby » de Roy Orbison, qui avait parlé du studio à son ami Buddy Holly. Quand il était encore sous contrat avec Decca, Buddy avait enregistré deux maquettes là-bas et une fois le contrat Decca enterré en janvier 1957, il fit logiquement son retour chez Norman Petty avec de nouveaux musiciens : Larry Welborn à la guitare et son vieux copain de classe et ami Jerry Allison. Vite séduit, Petty proposa de devenir son producteur, de financer les enregistrements — le tout en échange d’une cosignature des chansons, c’est à dire en échange d’une part majoritaire des droits d’auteur… Sans contrat de disques, passionné par son art, Buddy n’avait pas le choix, bien que ses chansons aient été composées avant cet accord. Paternaliste et manipulateur, Petty croyait toutefois en Buddy.

Une nouvelle version perfectionnée de That’ll Be the Day (en la, deux tons et demi plus bas) s’enrichit de chœurs de type Drifters et d’un solo de guitare. Buddy n’avait pas le droit de la sortir sous son nom pendant cinq ans, et il fallut trouver un nom de groupe. Il choisit avec J.I. Allison et le guitariste Niki Sullivan les Crickets [grillons], un insecte connu pour son chant — le préférant de peu aux Beetles ! Le nom fut très mal reçu par leur public, et les enregistrements furent refusés par Roulette et Columbia. Petty trouva alors un accord avec un éditeur chargé de les placer, Murray Deutch, le découvreur des Platters. Sans succès auprès d’Atlantic et ABC c’est Bob Thiele chez Coral, une petite marque filiale de Decca (!) qui a fait écouter les titres à ses supérieurs. Personne n’a rien remarqué chez Decca alors qu’ils étaient déjà propriétaires d’une première version de That’ll Be the Day, que Buddy n’avait, en plus, pas le droit de réenregistrer ! Leur refus fut cinglant, mais pour faire plaisir à Thiele, ils le laissèrent presser mille exemplaires sur une petite sous-marque oubliée, Brunswick, réservée aux ringards. Le contrat des Crickets ne fut signé que par ses musiciens pour éviter que le nom de Buddy Holly n’apparaisse et alerte Decca. Le style du chanteur avait mûri en un temps record. À dix-neuf ans il avait une maîtrise remarquable de son art et une solide expérience du studio. Enfin libre de contrôler la direction de sa musique, et avec l’aide technique de qualité de Petty, un des rares producteurs indépendants du pays, Buddy Holly enregistra en quelques mois une série de chefs-d’œuvre au son propre, clair et efficace. Il était maintenant un humble concurrent d’Elvis, mais surtout des Everly Brothers, dont le son du n°1 « Bye Bye Love » en ce printemps 1957 était proche du sien. Le rock reculait devant les coups de boutoir du scandale; Elvis enregistrait déjà des ballades sirupeuses, et le son du moment était celui de Ricky Nelson — un peu édulcoré. Quand Decca découvrit que les Crickets avaient pour chanteur Buddy Holly, celui-ci dût signer un autre contrat avec les disques Coral (une autre filiale de Decca) et abandonner les droits de sa première version de That’ll Be the Day pour éviter le procès. Il ne fut même pas prévenu que la nouvelle version était sortie en mai, et ce sans aucun succès. Words of Love sortit ensuite sous son nom chez Coral. Les deux titres avaient déjà été repris par The Ravens et The Diamonds. Buddy retourna enregistrer de nouvelles perles chez Petty, sans grand espoir, mais avec un nouveau système d’écho bricolé par l’ingénieur du son. Il rencontra aussi Peggy Sue, qui sortait avec son pote Jerry « J.I. » Allison. Son prénom collait mieux que « Cindy-Lou » à une nouvelle chanson enregistrée cet été 1957, et à laquelle Petty avait pour une fois réellement contribué (le passage « pretty pretty pretty Peggy Sue »). Le guitariste Niki Sullivan ne joue pas dessus et c’est lui qui commuta le micro de la guitare de Buddy vers la position « rythmique » pendant la prise, après le solo du chanteur. Buddy était tombé amoureux de June Clark, une jeune femme mariée, tandis que sa grande inspiration Echo McGuire était loin à Abilene. Il avait du succès, et connut plusieurs filles moins chastes qu’Echo, au point qu’il mit deux jeunes femmes enceintes, ce qui dans le contexte sexiste texan (IVG interdite et tabou) et la carrière montante de Buddy, fut réglé par un éloignement des mamans et deux adoptions. Il commença aussi une relation avec June et la supplia de quitter son mari. Elle refusa la rupture mais céda à ses avances…

That’ll Be the Day

C’est alors que That’ll Be the Day commença à se vendre à Buffalo, à Philadelphie grâce à des disc jockeys de radio. Coral/Brunswick/Decca investirent alors dans la promo. En juin, 50.000 exemplaires étaient écoulés et le groupe émerveillé a été invité à New York. On leur proposa de faire une tournée de concerts dans tout le pays, pour laquelle Petty leur fit acheter des costumes gris et toute une garde-robe, déduite de leurs revenus par leur désormais manager, qui prit le contrôle de tous les comptes en banque — et de leur argent. Dans sa feuille de route d’instructions au groupe, il était écrit dans la liste : « emportez une Bible et lisez-la ». À la mi-août, That’ll Be the Day s’était vendu à un demi-million d’exemplaires. C’était le triomphe. Buddy était invité aux émissions de télévision American Bandstand (où des couples dansaient la valse en smoking et robe longue au son du rock !) et, consécration, par le disc jockey Alan Freed, qui l’invita en tournée dans son spectacle « Holiday of the Stars » avec l’ami de Buddy, Little Richard et Larry Williams, King Curtis, Mickey and Sylvia… la vie dans un car avec une dizaine de groupes était très dure et les revenus ridicules. En octobre 1957, sous la pression de la gloire, riche et célèbre, Little Richard a renoncé à sa carrière pour entrer au monastère, un nouveau coup porté au rock.

Les Crickets jouèrent à l’Apollo, parcoururent le pays avec les Drifters, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, LaVern Baker, les Everly Brothers… la police arrêta un jour les deux cars et sépara les Noirs et les Blancs : un car pour les Blancs, et un pour les Noirs. Les publics noir et blanc étaient séparés par un rideau dans certaines salles. Un soir, ils n’ont pas pu jouer car les Noirs et les Blancs n’avaient pas le droit de jouer sur la même scène pendant un même spectacle. Le groupe fut aussi attaqué plusieurs fois par des petits amis jaloux… et le 23 septembre 1957, ils parvinrent au n°1 des ventes, et n°3 dans Billboard. L’excellent Peggy Sue est sorti trois jours plus tôt sous son seul nom, montant au sommet à son tour. Après trois mois de tournée où les Crickets sont devenus amis avec Eddie Cochran, Brunswick a sorti Oh Boy sous le nom des Crickets avec en face B Not Fade Away (aux percussions jouées à la main sur un carton, comme sur les succès d’Eddie Cochran) le 27 novembre. Surgit alors leur premier album au titre incomparablement ringard : The Chirping Crickets [« les grillons gazouillent »]. Le 1er décembre ils étaient dans l’émission prestigieuse d’Ed Sullivan. Le guitariste Niki Sullivan, épuisé par la tournée et fâché avec le batteur, quitta le groupe, qui continua en trio. À New York les frères Everly apprirent à Buddy la vie de vedette : où s’habiller, où sortir en boîte. Toujours sur leur conseil, d’élégantes lunettes Wayfarer qu’il ne cherchait plus à cacher. De retour chez lui, il se fit détartrer les dents, et acheta une Chevrolet Impala V8 modèle 1958. Oh Boy monta au n°10 à noël. D’épuisantes tournées se multiplièrent, avec des trajets en car extrêmement longs. Ils s’envolèrent pour Honolulu, puis pour l’Australie. À son retour, Buddy enregistra à New York pour la première fois sous la direction de Bob Thiele, au grand dam de Norman Petty, qui encaissa tout de même un tiers des droits d’auteur de Rave On, l’un des chefs-d’œuvre de Buddy Holly. Le chanteur y déploie tout son arsenal vocal, à commencer par ses fameux hoquets, sa signature. Après une seconde apparition chez Ed Sullivan, il s’envola pour l’Angleterre, où ses disques se vendaient très bien. Malgré l’horreur qu’il inspirait aux parents, le rock commençait à y percer timidement après la mode du « skiffle », un ersatz de rock lancé par Lonnie Donegan. Le rock était interdit à la BBC depuis la première émeute à un concert de Bill Haley en février 1957 : sans médias, sans radio (sauf quelques passages sur Radio Luxembourg), par simple bouche-à-oreille Buddy Holly était au sommet. Avec la pochette de l’album il était perçu comme un garçon plein de style, d’élégance, un trait qui manquait cruellement à l’Angleterre populaire de l’époque. C’est début 1958 que les Quarry Men engagèrent George Harrison à la guitare, devenant soudain les Beatles, dont le tout premier enregistrement fut une maquette de That’ll Be the Day. John Lennon et Paul McCartney construisirent leur style en écoutant Buddy Holly en boucle et ça s’entend.

Les disques d’or et les honneurs ont continué à pleuvoir sur Buddy Holly en 1958. La nouvelle de sa mort accidentelle le 3 février 1959, après un peu plus d’un an de succès, avec deux autres vedettes du rock, Ritchie Valens et The Big Bopper, embarquées à bord du même avion, est tombée comme un coup de plus porté à la musique rock. Buddy avait vingt-deux ans quand il mourut si tragiquement jeune. Quelques-unes de ses maquettes ont ensuite été retravaillées : des cordes y ont même été ajoutées avec un certain succès posthume. Elles figurent à la fin de cette indispensable anthologie.

Bruno Blum, juin 2018.

© Frémeaux & Associés 2020

1. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962 dans cette collection.

2. Lire les livrets et écouter The Indispensable Bo Diddley, volume1 1955-1960 et volume 2 1959-1962 dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 dans cette collection.

4. Lire le livret et écouter Race Records, Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 dans cette collection.

5. Lire les livrets et écouter The Indispensable Gene Vincent, volume1 1956-1958 et volume 2 1958-1962 dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1961 dans cette collection.

7. Lire le livret et écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 dans cette collection.

8. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Rockabilly 1951-1960 dans cette collection.

9. Écouter The Beatles Anthology - Volume 1, The Beatles at the BBC et The Beatles for Sale (Apple/EMI).

10. Lire le livret et écouter The Electric Guitar Story - Country, Jazz, Blues, R&B, Rock 1935-1962 dans cette collection.

11. Lire le livret de Gérard Herzaft et écouter Country - Nashville, Dallas, Hollywood 1927-1942 dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter Texas Down Home Blues 1948-1952 dans cette collection.

13. Lire les livrets et écouter Western Swing 1928-1944 et Bob Wills & his Texas Playboys 1932-1947 dans cette collection.

14. Lire le livret et écouter Country Music - bluegrass, honky tonk, West Coast, western swing… 1940-1948 dans cette collection.

15. Lire le livret et écouter Country Boogie 1939-1947 dans cette collection.

16. Lire les livrets et écouter The Indispensable Fats Domino 1949-1962

(six disques), Nat « King » Cole - The Quintessence volumes 1 & 2 et Louis Jordan 1938-1950 dans cette collection.

17. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Rockabilly 1951-1960 dans cette collection.

18. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Roy Orbison 1956-1962 dans cette collection.

19. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 dans cette collection.

20. Lire le livret et écouter Bill Haley & his Comets - Live in Paris 14-15 octobre 1958 dans cette collection.

The Indispensable Buddy Holly - 1955-1959

By Bruno Blum

John wore horn-rimmed glasses and when there were any girls around he’d whip ‘em off. But when Buddy came up he went, “Oh yeah, I can wear these.” The other reason why we loved Buddy is that he wrote his stuff; Elvis didn’t write his stuff. We loved Elvis, but he didn’t write. So Buddy wrote and played, and played the solos. He was a self-contained guy, which is what we’re trying to emulate. And the first thing we could not work out was the beginning of That’ll Be the Day. And then, I think, George came up with it.

— Paul McCartney

Elvis Presley became a rock ‘n’ roll phenomenon in early 1956. In the heavily racially-segregated context of the time, white teenagers massively adopting African American music created an unprecedented culture shock in the US: “Race” music (rock and roll, rhythm and blues, blues, etc.) by black artists was “crossing over” big-time, popularized by, firstly, Bill Haley and shortly thereafter, by Elvis, who’d both taken up this fresh and very exciting music.

Rock and roll by Fats Domino, Ray Charles (listen to Early in the Morning here), The Coasters/Robins (listen to Holly’s Smokey Joe’s Café demo), then Little Richard (listen to Ready Teddy and Send Me Some Lovin’), Bo Diddley (listen to Mona & Holly’s composition Not Fade Away, which is very much influenced by Diddley, and his successful version of Bo Diddley) and Chuck Berry (listen to Brown-Eyed Handsome Man) was successful.

These African-American artists, in turn, inspired many white, country music artists to play music derived from original Black rock forms, thus creating rockabilly, spearheaded by Gene Vincent, Bill Haley and Elvis Presley. Buddy Holly was one of those young enthusiasts. Like them, he blended country guitars to rock, which thus became rockabilly.

Holly had started off as a hillbilly (country) duo with Bob Montgomery; called ‘western’ music back home in Texas, country music was very popular, but, suddenly, impressed by an Elvis show, he too opted for rockabilly — white rock blending black rock and white hillbilly. However, like Roy Orbison, another rockabilly singer, Buddy Holly had true ambition, both as a composer and as a melody maker and so created a style all his own. He soon differentiated himself from pure rockabilly.

That’ll Be the Day, Every Day, Peggy Sue, Oh Boy, Rave On, Maybe Baby, Not Fade Away and Words of Love are among his most famous compositions. With them he expressed the tumults and joys of young love.

In Europe, his melodic, inspired style would become, along with the Everly Brothers’, one of the main influences on the young Beatles, who recorded a demo of That’ll Be the Day as well as Crying, Waiting, Hoping at the BBC and, more significantly, Words of Love on October 18, 1964 (for the Beatles For Sale album, released on December 4, 1964). Holly also left a deep mark on the nascent Rolling Stones, who recorded Not Fade Away. Released by Decca on February 24, 1964, this was their first hit record and it launched the group.

Buddy Holly backed himself on guitar, with an original style. He contributed to defining the fundamental, classic rock orchestration of years to come: singer-guitarist, second guitarist, bass and drums. After a few, early commercial failures, first by playing live country music, then with rock music on the Decca label, the release of That’ll Be the Day, issued under the name of The Crickets for legal reasons on May 27, 1957, was a revelation. By September, the tune was Number One in the UK and the USA. Released on September 23 that same year, Peggy Sue, his greatest classic, took him to new heights at the age of twenty. He had sixteen months left to live.

Lubbock, Texas

Charles Hardin Holley, aka “Buddy” Holly, was born on September 7, 1936 at 1911, Sixth Street, in Lubbock, Texas, a day’s drive from Dallas. This was at the heart of the Great Depression in one of the most conservative and religious cities in the US, with strict racial segregation and firearms carried everywhere. Alcohol remained strictly prohibited there until 1972. Dubbed “Buddy”, Charles Holley had two brothers and one sister. His parents were Laurence Holley, aka L.O., a Texan cook turned labourer in the Depression hard times, and Ella Drake (whose father had Cherokee blood. Her family were also related to the great 16th-Century English explorer & sailor, Sir Francis Drake). L.O was also the deacon of a radical Tabernacle Baptist church and was very poor. Buddy joined the Boy Scouts. The Holleys kept moving to ramshackle homes and all played music, except for L.O and around the age of five, Buddy won a five-dollar prize for playing a toy violin. After moving once too many times, he lost touch with his school friends and took refuge in music, taking piano lessons. He didn’t like it and his father got him a hock Harmony guitar.

In those days, country music united Texan people of all ages: folk, ballads, cowboys and campfire songs. Buddy liked The Carter Family, Woody Guthrie, Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Snow, Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers, Gene Autry, etc. There were country dances and radios broadcast live from the Grand Ole Opry, Louisiana Hayride, etc. Access to African American music by White people was totally barred by racial segregation and African-American blues was considered sin. Hank Williams’ breakthrough in the early 50’s showed that he was vulnerable and sensitive, a trait later found in Holly’s works.

Texas country music was ruled by the “western swing” style of Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys that was much influenced by the swing bands heard in Black dance halls. This “western” style contrasted with other country music styles. White rock found its roots in the irresistible, western swing-derived 1940s country boogie, which pinned sharp country-style guitars over black boogie-woogie and swing, and later morphed into rockabilly.

Buddy moved back to Lubbock and went to J. T. Hutchinson Junior High School again. He soon mastered the banjo (a four-string European banjo) and, aged thirteen, sang vocal harmonies with a guitar-playing school friend of his, Bob Montgomery. He also reconnected with Don Guess, who would later play bass and compose with him, and Jerry Allison, who was to become his drummer and friend.

He formed a country duet with Jack Neal (who had written songs with Don Guess) as Buddy and Jack. Buddy was doing well at high school in spite of his very bad eyesight (20/800) and started wearing glasses in 1954. He was particularly good in English and helped his carpenter brother building roofs; he liked drawing and working with leather. Buddy was a tall, likeable, helpful and self-confident kid. He was performing with Bob Montgomery and courting Echo McGuire, a student from a well-off family (who went to the Church of Christ, where any music was strictly forbidden). At sixteen Buddy “seduced” the young woman (with permission from her religious parents), which led to a “friendly” platonic relationship. Buddy’s well-behaved, pious side contrasted with that of other rockers of his generation, such as Little Richard or Jerry Lee Lewis.

Hillbilly and Western

On November 4th, 1953, Buddy and Jack sung live on the air at KDAV, the only 100% country music station in the USA. Their performance led to a live show every Sunday, where a few hillbilly tunes, including Memories, were later recorded. In just a few days they became “hillbilly & western” stars in Texas. Montgomery soon joined them.

In spite of prohibition, Buddy tried “moonshine” whisky but could not stomach alcohol. He started smoking Salem cigarettes at the age of sixteen. He admired jazz guitarist and composer Les Paul, in late 1954 he bought a Gibson Les Paul Gold Top. He would hide in his car to listen to blues radio shows from Louisiana (KWKH ) or Tennessee and secretly appreciated Black music, for which he risked a beating. In 1954-55 in Texas, his favorites — Bo Diddley, The Coasters, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James, and his big influence Hank Ballard could not be played publicly by a White person. Liking and listening to Black music was, itself, the beginning of the end of segregation, and artists such as The Drifters, Nat “King” Cole, Louis Jordan and Fats Domino were appreciated by many young Whites.

Buddy started hanging out on the edge of the Black section of the city. He met some blues musicians and decided to stop supporting segregation, which was rather daring for the time. He even called his cat “Booker T. Washington”. He was getting to be known locally. The duet opened for country stars at the Cotton Club near Lubbock, where African Americans were admitted because the club was outside of the city limits. Their radio show host, ‘Hi Pockets’ Duncan, became their manager and secured them gigs at the Clover Club in Amarillo. They were joined there by Sonny Curtis, a lead guitar player with whom Buddy shared his secret interest in the blues.

Elvis

Buddy Hall was a disc-jockey at KDAV. It was he who turned the station on to Elvis Presley’s first record, which melded expressive, highly emotive singing (on which African American culture had left its indelible mark) with exciting blues rhythms and a typically country-style lead guitar. Buddy and Sonny adored it, too.

On January 2nd, 1955, they saw the rising star of the country sing live. Elvis’ revolutionary show, in which he moved in a completely uninhibited way, and his rockabilly music broke all well-behaved country music codes. The entire country’s white youth fell for Elvis’ and Buddy Holly instantly took up a similar style.

Sonny Curtis gave up playing his violin (Memories) and learned to play guitar, in the style of Chet Atkins and Scotty Moore, Elvis’ guitar player. Don Guess quit the steel guitar and switched to double bass. Buddy started moving about more dynamically on stage and stopped holding back his vocal style, like he had done before in typical country music fashion. It seemed that he was possessed now by some inner fire. An archetypical rocker was born, and his group was soon in strong demand.

On February 13th, 1955, Buddy & Bob played opening for Elvis Presley in Lubbock’s Fair Park Coliseum at South Plains Fair. Elvis and Buddy shared some of their music tastes and became friends. Elvis was famous but hadn’t yet become the generation-defining phenomenon that he was to become a year later with RCA’s help. Buddy soon recorded a Baby Let’s Play House demo for which he copied Elvis’ rockabilly arrangement of this blues composition. Buddy was now playing several times a week and his fees were rising. 1955 was also the year Bill Haley had a huge hit record with “Rock Around the Clock”; African American artists such as The Penguins, Fats Domino, Frankie Lymon and Johnny Otis were being successful, Chuck Berry was issuing his first masterpieces and so was Little Richard. The rockabilly anthem “Blue Suede Shoes” was recorded at Sun Studios in December. Elvis kept right on filling White teen America with excitement, enthusiasm and more freedom than any previous generation had ever experienced.

At the age of eighteen Buddy spent the summer working as a navvy. He also met Little Richard and was becoming a bit of a rebel with his parents and the local police. At night he would go off alone to jam with rock groups, far away from the religious order that prevailed all around him. Girls would scream when he sang and the times of sexual abstinence were over. He now led a “double” life.

On October 14th, 1955, Buddy opened for Bill Haley and was spotted by Eddie Crandall. Crandall suggested to Elvis’ manager that he work with Buddy too, but the colonel was too busy and told him to do it himself, instead. “Rock ‘n Roll”, was originally a term taken from the Black vocabulary, but it was now trendy and becoming more popular all the time. Record companies were looking for rockabilly artists who might compete with Elvis Presley. At Decca Records, Paul Cohen offered Buddy a simple recording contract, not promising anything more. Buddy borrowed $1,000 from his brother, Larry, and bought a brown sunburst Fender Stratocaster and some conspicuous clothes: red coat, blue suede shoes, chartreuse sport jacket…

The first studio session, under Owen Bradley’s direction, took place in Nashville in early 1956, featuring the excellent Sonny Curtis on lead guitar (after Buddy’s death, Sonny would replace him as leader of the Crickets). Presley was becoming a superstar but Decca did not have similar belief in Holly. After a few records without proper promotion, one tour and an unsatisfactory version of That’ll Be the Day in July, Buddy had several arguments with Paul Cohen, who wouldn’t let him play his music the way he wanted it (see Disc 1, tracks 1-14). So, like the previous year, Buddy spent the summer helping his father and brother, Larry, an ex-Marine, this time setting tiles and doing carpentry.

Elvis was Number One as from August right through until December, while Buddy remained relatively unknown outside his immediate, local area. He sometimes needed protection at his own shows because of jealous boyfriends. He had also become Buddy Holly because of a mispelling on his contract. After a third session in November, 1956, and more arguments with Cohen, his contract was sent back to him in January of 1957.

By then the big rock ‘n’ roll trend of 1955-1957 was getting a huge backlash. An insidious denigration campaign, launched from and run by the conservative, puritan and racist forces of the US was striking back.

Norman Petty

In the spring of 1956, Buddy Holly had met Norman Petty, a somewhat shady character and a rather ordinary organ player who, although effeminate, was married to pianist and singer Violet Ann “Vi” Petty. With Jack Vaughn on guitar, Norman Petty and Vi had a hit song in 1954 with a version of “Mood Indigo” on the Columbia label and they gave small-scale concerts all around the country around that time.

A mediocre creator, Petty was a good sound engineer. He had built himself a small, one-track studio in Clovis, a small town on the New Mexico border. He recorded there with his spouse, an anxious woman whom he dominated completely. The studio had a few clients and Petty had made a demo there for Jimmy Self, later securing him a record contract with RCA, Elvis’ label. Aged twenty-nine, Petty was a bigoted Baptist. He kept a Bible around at all times and required his musicians to be devout and pray religiously when they got together in a circle after each good take.

To drink, smoke or curse was forbidden in his home. Both stingy and generous at the same time, he welcomed his clients in comfort; his fridge was always full and he never got paid until the recording was over (instead of renting the studio per hour). In exchange for his seemingly generous largesse, his clients signed contracts where they gave up part of their songwriting royalties, even when he hadn’t composed any part of a particular song (a common publishing-related practice at that time).

Petty had recorded Roy Orbison’s “Ooby Dooby” demo earlier, and Orbison had told his friend Holly about the studio. Buddy had recorded a couple of demos there while he was still under contract with Decca, so when his contract was buried in January, 1957, he went back to Norman Petty with some new musicians: Larry Welborn on guitar and his old school mate Jerry Allison on drums. Petty fell for Buddy right away and offered to become his producer and finance his recordings — in exchange for more than 50% of his songwriting royalties. Buddy had no real choice. Although the songs were actually composed before the deal, he had a passion for his art but no label. Petty was manipulative and paternalist, but he believed in Buddy and that was enough.

A new, perfected version of That’ll Be the Day (in the key of A, two-and-a-half tones lower) was enriched with Drifters-style vocal harmonies and a guitar solo by Buddy himself. But he was not allowed to issue songs under his own name for a period of five years at that point, so they had to find a band name. Together with guitar player Niki Sullivan and Jerry Allison, the trio chose “The Crickets”, an insect famous for its singing — and nearly opted for The Beetles! However, the new name was ill-received by their audience — and all recordings were rejected by Roulette and Columbia.

Petty then found a publisher likely to obtain a record contract. Murray Deutch had discovered The Platters, so he talked to both Atlantic and ABC. But it was Bob Thiele at Coral, a small label owned by Decca (!) who played the tracks to his bosses. No one noticed a thing at Decca, in spite of them already owning a previous recording of That’ll Be the Day, which, on top of everything, Buddy had no right to record again! Decca flatly refused a deal, but to please Thiele, they let him press 1,000 copies on a small, forgotten label called Brunswick, on which they usually issued outdated, “square” material.

The Crickets’ contract was only signed by the musicians to avoid having Buddy Holly’s name appear in print, or even anywhere — and thus risking a Decca lawsuit. The singer’s style had ripened in record time. Aged nineteen, he had mastered his art remarkably well and already had a lot of studio experience. Now able to control the production of his own music, and with quality technical help from Norman Petty, one of the very few independent producers in the country, over a period of a few months he managed to record a series of masterpieces with a clear, clean and efficient sound.

He was now one of Elvis’ humble competitors, though he was mainly competing with the Everly Brothers, whose number one record in the Spring of 1957, “Bye Bye Love,” had a similar sound. Meanwhile, rock‘n’roll music was wilting under the pressure of various media “scandal” assaults. Elvis was, by now, already recording commercial ballads and the sound of the day was Ricky Nelson — a bit toned down. When Decca found out the Cricket’s singer was Buddy Holly, he had to sign a new contract with Decca subsidiary Coral and give up all his rights to the first version of That’ll Be the Day to avoid being sued. He was not even informed that the new version was being issued in May — and was getting nowhere. Words of Love was issued next, this time under his own name on the Coral label. Both tunes had already been recorded by The Ravens and The Diamonds. Without much hope, Buddy went back to record more gems at Petty’s studio, this time using a new echo system built by the engineer. He also met Peggy Sue, who dated his friend and Crickets’ drummer, Jerry Allison. Her name also suited better Buddy’s new song “Cindy Lou,” which was recorded in the summer of 1957. For once, Norman Petty effectively contributed an idea, the “pretty, pretty, pretty Peggy Sue” bit. Guitar player Niki Sullivan did not actually play on the recording, but it is he who actually moved the guitar pickup switch back to the ‘rhythm’ position at the end of Holly’s solo.

As his muse, Echo McGuire, was far gone in Abilene, Buddy had fallen in love with a young married woman named June Clark. He had considerable sex appeal and had had several previous encounters with ladies less chaste than Echo. Two of them got pregnant, which, in the conservative, Christian, Texan context of the day (no abortion), resulted in both mothers moving away and having the children adopted. He, nevertheless, then started a relationship with June and begged her to leave her husband. She refused to leave him but did give in to his advances…

That’ll Be The Day

This is the point when That’ll Be The Day started selling, first in Buffalo and Philadelphia, thanks to local radio DJs. Coral/Brunswick/Decca then started investing in promotion. By June, 1957, 50,000 copies had been sold and the group was invited to New York City, filled with wonder. They were offered a tour of the entire country, for which Petty had them buy grey suits and a whole new wardrobe, which was deducted off their income by himself, their new manager. He also took control of all bank accounts — and all of their money. In his instruction sheet for the tour, he wrote the following line: “Take a Bible along and read it.” By mid-August, half a million copies of That’ll Be The Day were sold. This was nothing less than a triumph. Buddy was “consecrated” by the great DJ Alan Freed, who invited them on his “Holiday Of The Stars” show tour, along with Buddy’s friend, Little Richard and Larry Williams, King Curtis, Mickey and Sylvia…

Life on a touring coach was very hard and the income was ridiculously small. In October of 1957, under the pressure of glory and success, Little Richard retired to join a monastery, which was another hammer blow to rock’n’roll music. The Crickets played the Harlem Apollo and toured the country with The Drifters, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, LaVern Baker and The Everly Brothers… One day the police stopped the two coaches and separated Blacks and Whites: one coach for the Blacks, one for the Whites. In some venues, Blacks and Whites were separated with a curtain. One night in particular, they couldn’t play because Blacks and Whites were not allowed to play on the same stage during the same show.

The group was also attacked several times by even more jealous boyfriends/husbands… and on September 23, 1957, they reached Number One, with regard to national sales, and Number Three on the Billboard charts. The excellent Peggy Sue had been released three days earlier and climbed to the very top as well. Buddy was invited to sing on various TV shows, including American Bandstand (where couples danced the waltz in dinner jackets and long dresses to the sound of “Peggy Sue!”).

On November 27, after three months of touring, during which The Crickets became friends with Eddie Cochran, Brunswick issued Oh Boy under the name of The Crickets, with Not Fade Away on the B-side. This featured all percussion being played by Jerry Allison, by hand, on a cardboard box, just like Eddie Cochran did. Their first album also emerged suddenly, with the cheesiest title ever: The Chirping Crickets. On December 1, they played in Ed Sullivan’s prestigious TV show. Guitarist Niki Sullivan was, by this time, exhausted by the tour and, after an argument with the drummer, left the group to carry on as a trio. In New York, the Everlys taught them celebrity life: where to get hip clothes, which night clubs to hang out at, and so on. So, on their advice, he got some cool “Wayfarer” glasses. He was not trying to hide anymore.

Back home, Buddy had his teeth descaled and bought a 1958 Chevrolet Impala V8. By Christmas, Oh Boy was at Number 10. More exhausting tours multiplied, with extremely long drives between venues scattered far apart. They even flew to Honolulu, then on to Australia. When he returned, Buddy recorded in New York for the first time, under Bob Thiele’s direction, which worried Norman Petty, who was still cashing in on one third of Rave On’s songwriting royalties — one of Holly’s greatest masterpieces. On this song the singer deploys all of his vocal arsenal, including his signature “hiccups”.

Following a second appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show the band flew to England, where their records also sold well. In spite of horrifying most conservative parents, rock‘n’roll was, nevertheless, beginning to break there, following the popular “skiffle” trend, a rock’n’roll “sub-genre” launched by Lonnie Donegan in the UK. Rock’n’roll music had originally been banned by the BBC ever since the first riot at a Bill Haley concert in February of 1957. With no press and no radio airplay (except for a few plays on Radio Luxembourg), Buddy Holly reached the top just by word-of-mouth. The album cover suggested a stylish, elegant group, traits that working-class England very much lacked at the time.

In early 1958, The Quarry Men (already including John Lennon, who had founded the band in 1956, and Paul McCartney, who had joined the following year) appointed George Harrison on the lead guitar and subsequently became The Beatles in 1960. Their very first (and only) recording as The Quarry Men was a demo of That’ll Be the Day. Both John Lennon and Paul McCartney based and built their musical style through listening to Buddy Holly, and it shows.

Gold records and awards kept showering on Buddy Holly throughout 1958. The news of his accidental death, on February 3, 1959, after little more than a year of success, along with the death of the two other rock’n’roll stars, Ritchie Valens and J. P. Richardson “The Big Bopper” also aboard the plane, felt like yet another major blow to rock ‘n’ roll music. Buddy was only twenty-two when he died so tragically young. Some of his unreleased demos were later overdubbed: some of them resulting in posthumous hits, even with added strings. They can be heard at the end of this indispensable anthology.

Bruno Blum, June, 2018.

Thanks to Chris Carter for proofreading.

© Frémeaux & Associés 2020

1. Read the booklet and listen to The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962 in this series.

2. Read the booklets and listen to The Indispensable Bo Diddley, Volume1 1955-1960 and Volume 2 1959-1962 in this series.

3. Read the booklet and listen to The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 in this series.

4. Read the booklet and listen to Race Records, Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 in this series.

5. Read the booklets and listen to The Indispensable Gene Vincent, Volume1 1956-1958 and Volume 2 1958-1962 in this series.

6. Read the booklet and listen to The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1961 in this series.

7. Read the booklet and listen to Elvis Presley & The American Heritage 1954-1956 in this series.

8. Read the booklet and listen to The Indispensable Rockabilly 1951-1960 in this series.

9. Listen to The Beatles Anthology - Volume 1, The Beatles at the BBC and The Beatles for Sale (Apple/EMI).

10. Read the booklet and listen to The Electric Guitar Story - Country, Jazz, Blues, R&B, Rock 1935-1962 in this series.

11. Read Gérard Herzaft’s booklet and listen to Country - Nashville, Dallas, Hollywood 1927-1942 in this series.

12. Read the booklet and listen to Texas Down Home Blues 1948-1952 in this series.

13. Read the booklets and listen to Western Swing 1928-1944 and Bob Wills & his Texas Playboys 1932-1947in this series.

14. Read the booklet and listen to Country Music - bluegrass, honky tonk, West Coast, western swing… 1940-1948 in this series.

15. Read the booklet and listen to Country Boogie 1939-1947 in this series.

16. Read the booklets and listen to The Indispensable Fats Domino 1949-1962 (six compact discs), Nat “King” Cole - The Quintessence volumes 1 & 2 and Louis Jordan 1938-1950 in this series.

17. Read the booklet and listen to The Indispensable Rockabilly 1951-1960 in this series.

18. Read the booklet and listen to The Indispensable Roy Orbison 1956-1962 in this series.

19. Read the booklet and listen to The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 in this series.

20. Read the booklet and listen to Bill Haley & his Comets - Live in Paris 14-15 octobre 1958 in this series.

The Indispensable Buddy Holly 1955-1959

Discography

Disc 1

Buddy & Bob: Charles Hardin Holley aka Buddy Holly-v, g; Bob Montgomery-v, g; Sonny Curtis-v; Don Guess-b. KDAV Studio, Lubbock, Texas, August 1955 (radio broadcast).

1. Memories

(Bob Montgomery)

Charles Hardin Holley aka Buddy Holly-v; possibly Sonny Curtis-g; Larry Welborn-b. Wichita Falls, Texas, late spring 1955.

2. Baby Let’s Play House

(Arthur Neal Gunter)

Charles Hardin Holley aka Buddy Holly-v; Sonny Curtis-g; Don Guess-b; Jerry Ivan Allison aka J.I.-d. Wichita Falls, Texas, December 7, 1955.

3. Moonlight Baby

(Don Guess)

Note: “Moonlight Baby” was sometimes wrongly credited as “Baby Won’t You Come Out Tonight,” which is another song.

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v; Grady Martin-rhythm g; Sonny Curtis-lead g; Don Guess-b; Doug Kirkham-p; Produced by Owen Bradley. Nashville, January 26, 1956.

4. Midnight Shift

(Jimmie Ainsworth, Luke McDaniel as Earl Lee)

Note: “ Midnight Shift “ is also known as “Won’t You Come Out Tonight.”

5. Don’t Come Back Knockin’

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Sue Parrish)

6. Blue Days, Black Nights

(Ben Hall)

7. Love me

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Sue Parrish)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Sonny Curtis-g, lead g on 9; Don Guess-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d. Produced by Owen Bradley. Nashville, July 22, 1956.

8. Rock Around with Ollie Vee

(Sonny Curtis)

9. I’m Changin’ All Those Changes

(Don Guess, Jack Oliver Neal, James Rae Denny as Jim Denny)

10. That’ll Be the Day (Decca version)

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Jerry Ivan Allison)

11. Girl on My Mind

(Don Guess)

12. Ting-A-Ling

(Ahmed Ertegun as Nugetre)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v; Grady Martin-g; Don Guess-b; Floyd Cramer-p; Farris Coursey-d; E.R. Mc Millin aka Dutch-as. Produced by Owen Bradley. Nashville, November 15, 1956.

13. Modern Don Juan

(Don Guess, Jack Neal)

14. You Are My One Desire

(Don Guess, Jack Oliver Neal)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Jerry Ivan Allison-d. Holley Family Garage, Lubbock, Texas, late November/early December 1956.

15. Gone

(Eugene Rogers as Smokey Rogers)

16. Have You Ever Been Lonely

(Peter De Rose, George Brown)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Larry Welborn-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d; Niki Sullivan, Gary Tollett, Ramona Tollett-backing vocals. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty as Norman Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, February 24 or 25, 1957.

17. I’m Looking for Someone to Love

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Norman Eugene Petty)

18. That’ll Be the Day

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Jerry Ivan Allison, Norman Eugene Petty)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Vi Petty née Violet Ann Brady-p on 19; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d; Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, April 8, 1957.

19. Words of Love

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly)

20. Mailman Bring Me No More Blues

(Ruth Roberts, Bill Katz, Bob Thiele as Stanley Clayton)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g, backing v; Vi Petty née Violet Ann Brady-celeste on 19; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-cardboard box percussion, backing v; Niki Sullivan-backing v. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, May 29, 1957.

21. Not Fade Away

(Jerry Ivan Allison, Charles Hardin Holley as Charles Hardin, Norman Eugene Petty)

22. Everyday

(Charles Hardin Holley as Charles Hardin, Norman Eugene Petty)

Disc 2

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Vi Petty née Violet Ann Brady-p; Niki Sullivan-rhythm g; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, May 29, 1957.

1. Ready Teddy

(Robert Alexander Blackwell aka Bumps Blackwell, John Marascalco)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Niki Sullivan-rhythm g on 2; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d; The Picks (John Pickering, Bill Pickering, Bob Lapham)-backing v on 4, overdubbed on August 18, 1957. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, July 1, 1957.

2. Peggy Sue

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Jerry Ivan Allison, Norman Petty)

3. I’m Gonna Love You Too

(Joe B. Mauldin, Jerry Ivan Allison, Norman Eugene Petty)

4. Oh, Boy!

(Joe West as Sonny West, Bill Tilghman, Norman Eugene Petty)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Niki Sullivan-rhythm g, second lead g on 17; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d; The Picks (John Pickering, Bill Pickering, Bob Lapham)-backing v, overdubbed on October 12-14, 1957. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Tinker Air Force Base officer’s lounge, Oklahoma City, September 29, 1957.

5. An Empty Cup (And A Broken Date)

(Roy Orbison, Norman Eugene Petty)

6. Rock Me My Baby

(Frederick Earl Long as Shorty Long, Susan Heather)

7. You’ve Got Love

(Johnny Wilson, Roy Orbison, Norman Eugene Petty)

8. Maybe Baby

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Norman Eugene Petty)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; possibly Niki Sullivan-rhythm g; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d; The Picks (John Pickering, Bill Pickering, Bob Lapham)-backing v, overdubbed on October 12-14, 1957. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, March 1, 1957

9. Last Night

(Joe B. Mauldin, Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Norman Eugene Petty)

Same as above except Buddy Holly on guitar on 11 (Sullivan out), Sullivan on 10 (Holly out), July 12, 1957.

10. Send Me Some Lovin’

(John Marascalco, Lloyd Price)

11. It’s Too Late

(Harold Willis as Chuck Willis)

Same as above, possibly recorded on July 12, 1957.

12. Tell Me How

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Jerry Ivan Allison, Norman Eugene Petty)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Vi Petty née Violet Ann Brady-p except 13; C.W. Kendall-p on 13; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d; The Picks (John Pickering, Bill Pickering, Bob Lapham)-backing v. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, December 19, 1957.

13. Little Baby

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Norman Eugene Petty)

14. (You’re So Square) Baby I Don’t Care

(Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller)

15. Look At Me

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Jerry Ivan Allison, Norman Eugene Petty)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Jerry Ivan Allison-d. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, December or February, 1957.

16. Mona (I Need You Baby)

(Ellas McDaniel)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v; Al Caiola-g; Donald Amone-rhythm g; Norman Petty-p; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d; William Marine, Robert Bollinger, Robert Harter, Merril Ostrus, Abby Hoffer-backing v. Produced by Milton De Lugg. Sonny Lester, A&R. Bell Sound Studio, New York, January 25, 1958.

17. Rave On

(Joe West as Sonny West, Bill Tighman, Norman Eugene Petty)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-cymbals. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, February 12, 1958.

18. Well… All Right

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Jerry Ivan Allison, Norman Eugene Petty)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, February 13, 1958.

19. Fool’s Paradise

(Sonny LeGlaire, Norman Eugene Petty, Horace Linsky as Horace Linsley)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-cardboard box; Norman Eugene Petty-org. Produced by Norman Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, February 15, 1958.

20. Take Your Time

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Norman Eugene Petty)

DISC 3

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Joe B. Mauldin-b; Jerry Ivan Allison-d; Vi Petty née Violet Ann Brady-p and The Roses (Robert Linville, Ray Rush, David Bigham)-backing v overdubbed on February 19, 1958. Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, February 13, 14 or 15, 1958.

1. Think It Over

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Jerry Ivan Allison, Norman Eugene Petty)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g; Tommy Allsup-lead g; Joe B. Mauldin-b on 2; George Atwood-b on 3; Jerry Ivan Allison-d; The Roses (Robert Linville, Ray Rush, David Bigham)-backing v overdubbed on May 27, 1958 (on 2 only). Produced by Norman Eugene Petty. Norman Petty Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, May 25, 26, 1958.

2. It’s So Easy

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, Norman Eugene Petty)

3. Heartbeat

(Bob Montgomery)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v; Sam Taylor-as; Al Chernet-g; Georges Barnes-g; Sanford Bloch-b; Ernest Hayes-p; David Francis aka Panama Francis-d; Philip Kraus-d; Helen Way, Harriet Young, Maeretha Stewart, Theresa Merritt-backing v. Produced by Dick Jacobs. New York City, June 19, 1958.

4. Early in the Morning

(Walden Robert Cassotto as Bobby Darin, Woody Harris)

5. Now We’re One

(Walden Robert Cassotto as Bobby Darin)

Note: “Early in the Morning” is based on Bob King’s “It Must Be Jesus” as performed by The Southern Tones (available on the Roots of Soul set, FA 5430 in this series), on which Ray Charles also based his famous “I Got a Woman” (also available on the Roots of Soul).

Posthumous productions

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, acoustic g. Buddy & Maria Helena Holley’s apartment, 11 Fifth Avenue, New York City. December 5, 1958. Overdubs added after Buddy Holly’s passing: Donald Amone-g; Andrew Ackers-p; Sanford Bloch-b; David Francis as Panama Francis-d; The Ray Charles Singers-backing v. Produced by C. John Hansen aka Jack Hansen, June 30, 1959.

6. Peggy Sue Got Married

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly)

Same as 6, Holly’s voice and guitar recorded on December 3, 1958. Overdubs made on January 1, 1960.

7. That’s What They Say (Version #2)

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly)

8. What To Do

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly)

Same as 6, Holly’s voice and guitar recorded on December 14, 1958. Overdubs made on January 1, 1960.

9. Crying, Waiting, Hoping

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly)

Same as 6, Holly’s voice and guitar recorded on December 15, 1958. Overdubs made on January 1, 1960.

10. That Makes It Tough

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly)

Same as 6, Holly’s voice and guitar recorded on December 17, 1958. Overdubs made on January 1, 1960.

11. Learning The Game

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g. Holly’s voice and guitar recorded at Holley’s Family Garage between December 1956 and January 1957. Overdubs added at NM Studio, Clovis, New Mexico circa May 1962 by The Fireballs: George Tomsco-g; Stan Lark-b; Doug Roberts or Eric Budd-d. Produced by Norman Petty.

12. Bo Diddley

(Ellas McDaniel)

13. Brown-Eyed Handsome Man

(Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry)

Same as 12. NM Studio, Clovis, New Mexico, between February and April 1956, overdubs added circa June 1962.

14. Baby Won’t You Come Out Tonight

(Don Guess)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g. Holly’s voice and guitar recorded at Buddy Holly & Maria Helena Holley’s appartment, 11 Fifth Avenue, New York City, between January 1 and 20, 1959. Overdubs added at NM Studio, Clovis, New Mexico by The Fireballs: George Tomsco-g; Keith McCormack-rhythm g; vocal chorus, b, d, possibly mandolin, 1962.

15. Wait Till The Sun Shines Nellie (Overdub Recording Session Clovis)

(Andrew Sterling, Harry Von Tilzer)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v, g. Buddy Holly & Maria Helena Holley’s appartment, 11 Fifth Avenue, New York City, between January 1 and 20, 1959.

16. Smokey Joe’s Cafe

(Jerry Lieber, Mike Stoller)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v; Abraham Richman aka Boomie-ts; Al Caiola-g; Sanford Bloch-b; Ernest Hayes-p; Doris Johnson-harp; Clifford Leeman-d; Sylvan Shulman, Leo Kruczek, Leonard Posner, Irving Spice, Ray Free, Herbert Bourne, Julius Held, Paul Winter-violin; David Schwartz, Howard Kay-viola; Maurice Brown, Maurice Bialkin-cello. Produced by Dick Jacobs. New York City, October 21, 1958.

17. True Love Ways (Mono Mix)

(Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly, NormanPetty)

18. It Doesn’t Matter Anymore (Mono Mix)

(Paul Albert Anka)

19. Raining In My Heart (Mono Mix)

(Boudleaux Bryant, Felice Bryant)

20. Moondreams (Mono Mix)

(Norman Eugene Petty)

Buddy Holly a surgi du Texas en 1957 comme le vent nouveau du rockabilly puis du rock tout court, montant au numéro un avec une série de succès internationaux raffinés comme « Peggy Sue ». Les Beatles ont construit leur style en apprenant ses morceaux, et le premier succès des Rolling Stones était une chanson de lui. Bruno Blum raconte ici l’histoire d’une légende parmi les légendes : chanteur dont la signature des « hoquets » rend son style inimitable, guitariste soliste, brillant compositeur mélodiste, il fut une révélation promise à une longue carrière au sommet. Seize mois plus tard, son avion s’écrasait, le tuant sur le coup à l’âge de vingt-deux ans.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX