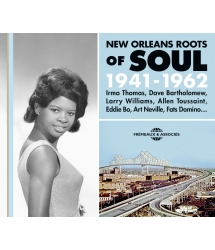

« A Losing Battle As you might expect after looking at that track-listing, this collection offers an excellent overview of the bluesier side of New Orleans music from within the stated time-span. The only issue I have is that this is intended as a look at the roots of soul music in New Orleans, and in that it is a little less successful. The first CD includes the wild Reverend Utah Smith and the rather more restrained Mahalia Jackson, with both providing indisputable evidence that the greatest part of the roots of soul music lie in gospel. The remaining tracks tend to have been picked for specific instances: Satchmo’s ‘Mack The Knife’ is here because it uses a gospel rhythm and Armstrong uses some vocal techniques also common in gospel music, and many of the blues tracks are here because “blues was fundamentally an extension of Negro spirituals”. Hmmm – the music is still wonderful though, and the thought did occur to me that for once a theme such as this set has would have been a perfect reason to include Guitar Slim’s ‘The Things That I Used To Do’ in its track-listing, not only for the vocal but also due to Ray Charles’ involvement. I am not quite sure as to why Frankie Lee Sims and Slim Harpo are here, but according to the notes, Roy Brown, who has been called “the first soul singer” and his imitator Litt le Mr. M idnight are present because their numbers influenced ‘Heartbreak Hotel’… The second CD again contains plenty of top notch Crescent City sounds, and demonstrates (to a degree) that rock and roll was also a factor in the evolution of soul music, and whilst Clifton Chenier’s ‘My Soul’ fits the bill in some ways, it is chiefly inspired by Little Richard (who isn’t here, despite having recorded in New Orleans, having been well-covered on Frémeaux’s collection, “The Indispensable 1951 – 1962”). Eddie Bo’s ‘I’ll Do Anything’ and Snooks Eaglin’s ‘That Certain Door’ do begin to approach what we know now as soul music, with discernible influences from Sam Cooke and Ray Charles respectively. These elements obviously become stronger on the third CD, with rock and roll tailing off but certainly leaving a trace, though the main difference is in the vocal delivery, and the prevalence of tracks by Irma Thomas also perhaps exemplifies the contribution of women to the new music. There are still examples of novelty items – as for example, Reggie Hall’s ‘The Joke’ – but the rhythms are unmistakeably New Orleans, and it is impossible (and perhaps futile) to say just where rhythm and blues ends and soul music starts – though maybe the latter could be at the start of Benny Spellman’s ‘Fortune Teller’. As a collection pointing out the diverse factors that combined with gospel in New Orleans to produce the city’s often very distinctive soul sound, I guess this works OK. As a collection of wonderful Crescent City music, it is hard to beat! Get out your favourite tipple, pick up John Broven’s book, “Walking To New Orleans” (or “Rhythm & Blues In New Orleans”, if you prefer the later title), put this on and enjoy.”

By Norman Darwen – BLUES & RHYTHM

By Norman Darwen – BLUES & RHYTHM